|

6/9/2021 0 Comments On Restlessness Vision of a sunrise near Douglas, Wyoming. My pipeline inspection equipment sits roadside in the foreground. Vision of a sunrise near Douglas, Wyoming. My pipeline inspection equipment sits roadside in the foreground. Originally published December 10, 2020 In the first piece I wrote for whatever this series of essays is becoming, I blithely noted a lifelong tendency toward restlessness. It’s a force that has driven research papers, inspired literature, informed film, and, in real-life situations, has ripped apart families, ended jobs, and launched fanciful and ill-fated dreams by the millions. A worthy topic, no? Here’s one small slice: In my primary career, that of a print journalist, I worked for ten newspapers (1) in seven states (2) over the course of twenty-five years (1988 to 2013). The shortest stint in a job was three months (hello, The Olympian, and the tumultuous year 2000 (3)). The longest stint was the final one, seven-plus years at The Billings Gazette, from summer 2006 to late fall 2013. In all of those years and all of those moves, I would pull up the stakes and fill the UHaul trailer for many reasons—money (4), status, opportunity, a sense of running to or running away—but the only factor that cut across every decision was this one: There looked better to me than here. That’s restlessness. If you read a lot of pop psychology (5), you come across the phrase “Wherever you go, there you are.” It has a subtle efficacy, straddling the line between inane (it is what it is) and something much more profound. In my case—and, I suspect, in many cases—it manifested like this: I could spot another job (believe it or not, newspaper gigs flourished in the early years of my career), I could apply for it and get it (because I was good at what I did), and I could pack up all my crap and haul it somewhere new, put down first and last on an apartment, find a new grocery store and some restaurants that suited me, meet new co-workers and bosses, and make a startling, yet thoroughly unsurprising realization days or weeks later: I’m the same broken jackass I was at the last place! It took me a long time to learn that I wasn’t feeding the part of me that required some care, the part that had yet to suss out the important differences between fulfillment and happiness amid the considerable overlaps. Not long after my initial career ended, I was picking through the debris field of a marriage with a counselor’s help, and with a lot of reflection and reading, some of these concepts started to click for me. I said to her: “Jesus. I must be the dumbest man alive not to have figured it out before now. (6)” And she smiled at me the way my mother sometimes does when I am in the vicinity of a realization without actually arriving there. “You’re in your mid-forties,” she said. “That’s when most men get it, if they get it at all.” (7) I don’t think I’ve gotten it. Sometimes, I think I’m asking the right questions, though. That’s progress. I followed my stepfather into journalism. The difference between us—and it’s vast—is that the job was something he did, not something he was. I used to think I’d figured out something vital that had eluded him, that by pouring myself into the job and remaining mobile (no kids, no attachments), I was making my career work for me. That was an illusion. Truth was, the job was working me, and I was willingly giving it some of my best years without insisting on my share of that time. My stepfather, meanwhile, rode out the vicissitudes of employment in a single place. Whether the job was good or bad or something in between, whether the bosses were genuinely caring or ogres, he did his work and came home to his family and his home and his life. He knew the difference between durable fulfillment and transient happiness. Like many dumbasses, I thought I was so smart. Let’s get back to restlessness. Certainly, that’s a condition that can lead a guy to choose the fleeting over the sustainable (8), to think he’s improving his lot when he’s really just going deeper into the hole. Restlessness, in itself, is not the problem. But restlessness is a gateway to transformative decisions, and those can be problems. Restlessness, applied well, can be a good and useful thing. And if restlessness is in you, I believe it’s there to stay, so better to manage it than to be managed by it. My newspaper career ended in 2013, and in the denouement, I was luckier than most: I granted myself release on my own recognizance. My first few novels had started to sell (9), I saw an opportunity to go, and I went. That first year of not having any obligation that I didn’t willingly take on, I slowly unwound the spring in my chest. I wrote when I wanted to write, I played golf when I wanted to do that, I traveled, I made merry, I finished crashing my first marriage on the rocky outcroppings of incompatibility and disregard. And somewhere in there, I felt the old stirring again. I wanted something to do, something to learn, somewhere to be. I was bored, a condition that’s the precursor to restlessness, which in turn is the spark that leads to decisions, good or bad. This is how I became a pig tracker. (10) In mid-October 2015, after a few weeks of dropping inscrutable hints about what I was up to, I wrote this on Facebook: I'm working on a pipeline crew, if I haven't been perfectly clear in my pig ramblings this week. Specifically, I'm a pig tracker. A pig is a tool placed in the pipeline that runs from point to point. Different pigs have different uses. Some clean. Some scan the interior of the pipeline. Some purge. And so on. A tracker stays in front of the pig—the tracker hopes—and records its passage at various crossings, gathering information on time, speed, etc. On a long, gentle run like this one, where the pig is moving about 3 mph and has to cover about 330 miles, that means the trackers work in shifts, day and night, 24 hours daily, all the time. We've been at it since Wednesday morning. We have a ways to go yet. I'm on the night shift. Midnight to noon. Then I find a hotel somewhere down the line and I bang out some sleep. I just finished that part. It's a weird, thrilling, lonely thing to skulk around the pipeline in the dark pitch of night. There's a lot of hurry up and wait on this job. There is, occasionally, a lot of hurry up and hurry up. You have to anticipate. You have to react. You have to figure out time and distance. It's fun. It's tedious, too, on occasion. Three days (nights) in, I'm exploring new frontiers of exhaustion. I'm reinforcing an old lesson, that Super 8's are, in many cases, not so super, and that Comfort Inns are not so comforting. … What I love is that I'm seeing the America I don't know well. Dirt roads and empty precincts and ghost houses and forgotten cemeteries, and a million other things. … I'm not doing it for money, although I'll certainly take it. I joke sometimes that I do it to stave off boredom, but that's too glib by half. No, it's something else. A chance to see and do and learn. All my life, I've been touched with wanderlust, that compulsion to see beyond present horizons. But I'm getting older and more rooted … I don't wander the way I used to. I miss it sometimes. Here, I can do it on my particular terms—work when I want it, without a desk on some office island, without some new corporate paradigm being triangulated by tiers of bosses. It's me and my night-shift buddy and our day-shift counterparts and the pig. We all keep rolling on. Pig tracking falls into the good-decision bucket. It's never been more than an occasional job—too many other things to do: books to write, stories to edit, magazines to design, life with Elisa to savor—but the work speaks to both who I am and what I’m fundamentally interested in. Time and speed and distance, man. Wherever we are, however we live, those are the measurements that build our equations. Without restlessness tugging at me, pestering me, maybe I never see that in such sharp relief. Endnotes (1) Deep breath: Fort Worth Star-Telegram; Peninsula Clarion; Texarkana Gazette; Owensboro Messenger-Inquirer; Dayton Daily News; Anchorage Daily News; San Jose Mercury News (twice); San Antonio Express-News; The Olympian; The Billings Gazette. (2) Shallower breath: Texas (thrice); Alaska (twice); Kentucky; Ohio; California (twice); Washington; Montana. (3) In less than a calendar year, I moved from San Jose, Calif., to San Antonio to Olympia and back to San Jose, where I clearly should have just stayed in the first place. (4) Not too damned much of it, in retrospect. (5) Guilty. (6) Hubris dies hard. (7) Men are in a lot of trouble. More on this later, I’m sure. (8) Guilty, many times. (9) Talk about transience. It was glorious while it lasted, though. (10) The main character in my upcoming novel, And It Will Be a Beautiful Life, is a pig tracker. This is not a coincidence.

0 Comments

6/9/2021 0 Comments The Shape of TimeOriginally published December 3, 2020

Just when you think Facebook has turned you away for good with its money- and data-grubbing perniciousness—and I do think this, on the regular—a friend posts something that commands your attention and sends you down the rabbit holes of memory and easy information, among the few reliable outposts in a pandemic that has separated us from each other. The compelling headline: “The Rare Humans Who See Time & Have Amazing Memories.” The friend who posted it, Ingrid Ougland, commented: “I see the months of the year as this sphere or oval, with December and January at the top, spring months slide down to the right, the summer months are at the bottom and kind of flat, then we climb back up with the fall months. I can’t visualize it any other way!” Envy was mine. I don’t see time that way at all. If anything, I see it in the old-timey movie effect of the passage of days, calendar sheets flying off in the wind, and suddenly Joseph Cotten (1) is a grownup standing in a place once occupied by a boy. Seconds tumble into minutes tumble into days tumble into weeks and months and years. Time compresses and stacks up, and I occasionally marvel that a colleague, blessed with what seems to be boundless youth, is, in fact, in his mid-thirties and should probably think now about doubling his 401(k) contribution. I wish I had (2). I would love to see coming time in colors or shapes, if only to make the inevitable passing of it more interesting. Upon thinking about it more—and herein lies the gift of Ingrid’s post: subsequent ruminations on time (3)—I realized that rather than seeing the days to come in some sort of order, I account for the days gone by with a storage system that’s varied in its cross-referencing and startling in the level of detail it allows me to access long after the time has slipped my grasp. It’s difficult to get at proving this thesis with any degree of abstraction, so here is a concrete example pulled from the archives, such as they are. Summer of 1976 A basic fact before we proceed, as it will clarify this anecdote and, in all likelihood, future writings: My mother and father divorced in 1973, when I was three years old. This is not an event that causes me to look backward in wistfulness, wondering if things might have gone better for me had those crazy kids stayed together. Indeed, things almost certainly would have been worse for at least two of us (my father, alas, never had it so good). So, please, if you feel compelled to pity, exercise it for a freckle-faced kid in some alternative universe who had to grow up in that household under the umbrella of that marriage. I’m fine. Really. What their breach did saddle me with was a sort of bifurcated childhood—two wildly different existences that I had to stitch together as a whole. During school months, I lived in a suburban house out of central casting, with two and sometimes three siblings (my stepbrother Keith being the wild card there), a mother who ran the homefront operation and a stepfather who worked hard and was present to his family life. Call it Cleaver-esque if you wish. That’s not an entirely on-target assessment—there are a few sprinkles of Yours, Mine and Ours, too—but if shorthand is your thing, I’m not going to let us get derailed on the particulars. Once school was out, my father would send for me, and I would spend summers with him in remote precincts of the West. Dad was an exploratory well digger, a job that scarcely exists anymore. (Slight deviation for self-promotion: My second novel, The Summer Son, will satisfy even the heartiest appetites for tales about well-digging.) He would drive from job to job with his truck-mounted drilling rig and a crew of helpers (sometimes one, usually two, and when I was around, I’d make three—or maybe two and a half) and would dig test holes that were subsequently detonated and picked over by geologists, whose task was to determine whether the findings warranted further extraction. These jobs lasted for varying lengths—sometimes a couple of weeks, sometimes a couple of months—and so I have this passel of childhood summers spent in such places as Montpelier, Idaho, and Baggs, Wyoming, and Limon, Colorado, and Sidney, Montana, and Price, Utah. I slept in motel rooms and on fold-out couches in fifth wheels, and, occasionally, in tents. Every morning, I’d ride with my father and his crew out to the fields where they were working, my sleepy head bouncing on Dad’s shoulder as he made the daybreak commute. We spent the summer of 1976 in Elko, Nevada, and here’s where the cross-tabbing of memory comes in. I remember it was ’76 because Dad’s helpers were my new uncle Barry and my new stepbrother Ronnie (4). I remember because Dad and his new wife and Ronnie and I were jammed up in a Holiday Rambler, often unable to escape each other, and I remember that the fissures in the marriage were almost immediately exposed by such unceasing proximity. I remember because “Play That Funky Music” was ever-present on the radio, and because I told Ronnie that I liked “Silly Love Songs” better and he told me I was just a dumb kid. I remember because, one day, another family in another trailer pulled in and set up camp, and their kid, a few years older than I was, punched me in the nose, bloodying it (and, perhaps, contributing to my fear of such confrontations). I remember because Dad and Uncle Barry responded to this assault in a way that can be described, only with considerable charity, as disproportionate. They carried baseball bats to the other family’s campsite, waggled the lumber with menace, and suggested those folks move along. Dad still tells this story from time to time, when he gets enough alcohol in him to open the dark rooms of his recall, and he always finishes with a laugh and a “man, you’ve never seen anybody drive away so fast.” I remember because I have to live with two distinct reactions to that sight, separated by years of reconsideration: In the moment, as a bloodied little boy, being in awe of these men who stepped in on my behalf, as if they were superheroes. And now, much older than either man was that day, wondering what the hell was wrong with them. Forty-four years’ worth of calendar pages have been cast to the wind, and I can sit here today and close my eyes and see the terror on the faces of that man, his wife, and their boy. I am much more in tune with how scared they were than I am with how I felt as a six-year-old who watched the scene unfurl. Summer of 2006 On Day 1 of my two-day move from California to Montana, I skirted along Elko on Interstate 80, and recall was stoked not just by the name but also by the bends in the highway and by the hills in the distance. I guided my pickup-UHaul combo off the interstate and, with neither GPS nor memory of the name of the campground we had stayed in thirty years earlier, I drove right to where it was. I knew the direction and the topography, I knew the hill it sat upon, and I knew the turns I had to make to get there. Had it occurred to me that this was unusual, I might have made more of it, but I’d been doing similar things in other places throughout my adult life, and I’ve continued to do it since. Drop me most anywhere I’ve spent an appreciable amount of time, whether as a child or a man, and I can find my way to the places I occupied in some past era of my life. And once I’m there, the time gone by indeed has shape and color. It settles uneasily atop or alongside whatever is happening there now. I can stand in front of my first house, off Poison Spider Road in Mills, Wyoming, as I did this past summer, and I will see the boxy white house with the single-car garage, ever-present in my memories since I last lived there in 1978, and I will also see what it is now: a sort of cinnamon red, the garage long ago converted into more living space, the street out front paved rather than dirt and gravel. I can connect with what was and allow it to coexist with what is. I have to. There is no other choice. Time is a slow-motion wrecking ball—it wipes out businesses that once existed on corners, housing developments, schools, the names by which we know things. Few human constructions can survive it. But none of that matters if it’s the corners to which you’re beholden and not what sat upon them while you were passing through. Those corners call to me. Endnotes (1) I’m not sure why Joseph Cotten popped out of the ol’ cranium for that example. I’m not terribly familiar with the bulk of his work, although he looms large with me for two reasons: First, Shadow of a Doubt might be the best movie ever, and yes, I’m willing to fight you. Second, I always momentarily confuse him with Josef Sommer, which is thoroughly inexplicable. (2) Seriously, retirement is a pipe dream. I’m going to have to die with my hands on the keyboard. (3) I mean, I’m not Proust, but I do spend an inordinate amount of my energy ruminating on the illusions and erosions of time. (4) While it’s true that I’m an ardent believer in the benefits of a necessary divorce, I really would like to urge those among us who cannot sustain the institution of marriage (in this case, I’m looking at you, Dad) to keep the rest of us out of it. At one point in my young life, I had three brothers and three sisters, thanks to the kudzu-like entanglements of several mergers. And then, with the stroke of a divorce judge’s pen, half of them were gone. I did not get a vote in the decision to add these sort-of siblings in the first place. Nonetheless, I accepted them as my own and loved them. I also didn’t get a vote in their departure. It sucks. 6/9/2021 1 Comment Still Fighting ItOriginally published November 26, 2020

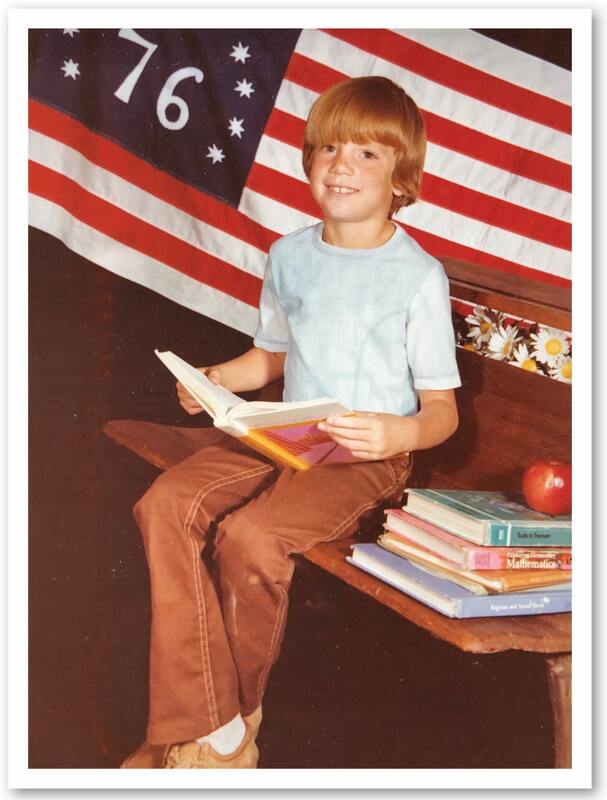

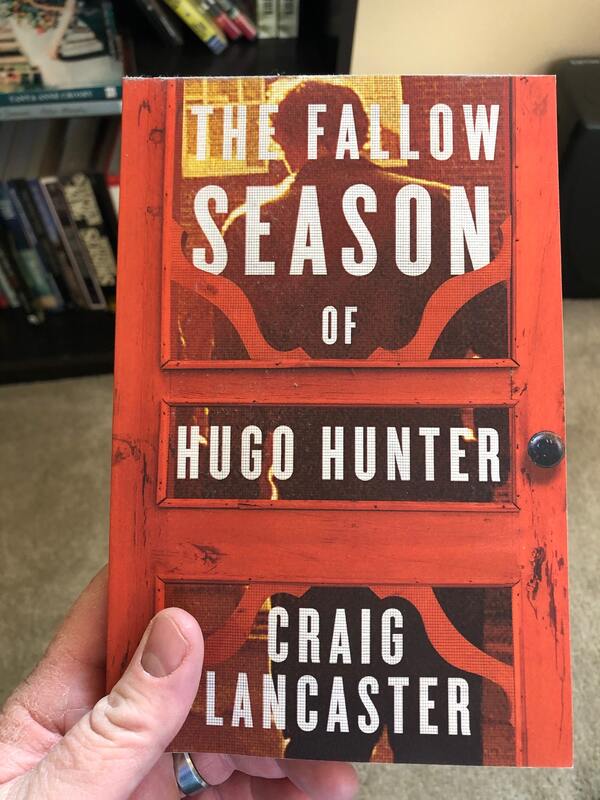

When I was nine years old, my stepfather picked me up from school one day and took me to a junkyard somewhere between downtown Fort Worth, Texas, and the middle-class suburb where we lived. We went into a squat cinderblock building with a couple of slat windows and scant ventilation, a place where men worked and sweated, and even today, forty-one years later, I can remember the air that hung heavy with that aroma of ancient perspiration. There, we met a man named Gary Barcroft, the head honcho of Little John’s Wrecking Yard Boxing Team. He was a man of hard angles, with a placid face and a harsh voice, and my stepfather handed me over and gave Gary permission to make a fighter of me. Actually, now that I reflect on it, that ambition was probably too lofty for the likes of the kid I was. What my stepfather hoped, I think, is that I might become unafraid of being punched, because that pervasive fear was coloring my interactions with other kids I knew, who could smell the fear on me and wanted to have a go. I think my stepfather’s aims that day were entirely pragmatic. A kid who can fight = a kid who doesn’t get bullied. I doubt he had his eyes on any notions that were larger than the moment demanded. And yet … I mentioned in a previous post that one of my best friends and I have bonded, in part, over the fact that we’re both big guys who look like bruisers but who don’t have any desire to rumble with anybody. This isn’t just a function of our current ages; believe me, we’re both well aware of how pathetic it would for a fifty-something and a sixty-something to go around tossing knuckles. Even as a younger man, with less of a handle on my rage and, perhaps, more of an excuse to give it an outlet, I wasn’t that guy. And yet, on occasion, trouble came sniffing around me. When you’re a big guy, you’re every bit the target that a little guy is—perhaps not to someone who doesn’t want a hassle and can find easier marks, but certainly to the alpha who seeks dominion or to the guy who thinks he can get his by taking yours. An example: Thirty years ago, I was playing pickup basketball at the Y in downtown Fort Worth, back when I had endless wind and knees that didn’t groan under my weight. The publisher of the newspaper I worked for at the time was on the court, too, and the first time we divvied up teams, he and I ended up on opposite sides, and he slapped my chest and said “I’ve got the big man.” I knew what that was, even at twenty years old. He didn’t know me—I was just a low-level correspondent in one of his far-flung suburban bureaus—but he knew what I was. I was his trophy that day. Events unfolded predictably. He pestered me. Jabbed me. Stretched the thin line between aggressiveness and assholery till it snapped. Taunted me. Tried to get a reaction from me. I wasn’t giving that up. I’m not claiming here that I was in possession of endless patience. It’s just that I knew where an escalation led. There’s a violent turn that such encounters can take, and once that happens, everybody involved becomes known to each other. No way would the outcome of such an encounter favor me. I wanted to keep writing newspaper stories and cashing checks without this guy being aware of my existence. At one point, late in a game, I got him on my back, jutted my ass end to keep him there, called for the ball with an upraised right hand. Once I had it on my palm, I dropped my left elbow dead center into his chest, heard the breath go out of him, a most satisfying deflation, and spun to the hoop and scored. When the game ended, I gathered up my stuff and went home, no words spoken, no outward satisfaction at my rejoinder. Me 1, Provocateurs 0. Gary Barcroft is the guy third from the right in the old picture above. It was taken in 1963, sixteen years before he met me. In 1979, the man was as good as his word. He put me on a heavy bag. Taught me how to beat out a rhythm on a speed bag. Instructed me in the ways of skipping rope. Sent me out on long runs with other fighters, from pipsqueaks like me on up to some of the up-and-coming pros in Fort Worth. Got me in the ring, moved me around, turned sparring partners loose on me. He taught me. I learned to throw the basic suite of punches—not especially well, as there was little that could be done about my substandard athleticism or my lack of foot and hand speed, but well enough to say, OK, the kid is ready for a real fight. I got one in Waco, ninety-some miles south. My parents and little brother and sister went down to see it. Gary was the referee, and one of his assistants was my cornerman. The bell rang, I lumbered out, threw a punch, left it dangling out there, and the other kid hit me directly in the nose. I dropped my arms, started bawling, and Gary ended matters. Abject humiliation, the worst I’ve ever felt, poured over me. The memory, even now as I type this, is sticky with failure and shame. I suppose my folks would have been fine with a lost night and a long drive home and no more boxing for me, but I went back to the gym the following Monday. I fought again the next Saturday and went the full three rounds. It was another loss, in that the other kid’s arm was raised by the referee, but it was also the biggest win ever. That season of boxing ended with my holding a 1-8 record and emerging into the rest of my life with a surety that I could handle myself in a physical confrontation. Funny how one never really showed up after that. Oh, I had a few boyhood rows with neighborhood kids, and I’d lose some and win some, but the gift of boxing is that it just wasn’t worth the time of anyone who knew me to throw fists. I might lose, but I wouldn’t make the winning easy for the other guy. Confidence and security come with that. For some time that season and beyond, I harbored fanciful dreams of fighting professionally, but both my record and my latent suburban softness exposed the incongruity of my capabilities and my fleeting aspirations. I had a trainer that year who wanted to see if I had some pent-up rage and whether he could coax it out of me. Well, I didn’t, at least not in any quantity that was useful to him--I was freaking nine—and his methods stood at odds with the limits of my comprehension. He would tell me about the great Roberto Duran and how he would convince himself before a fight that the man across the ring had done horrible, unspeakable things to someone Duran loved, to the point that his mind accepted the premise and his hands would chop down the opponent who’d been reduced to a mere proxy. It was jarring to hear that talk when I was a fourth-grader, and it remains jarring to consider at age fifty. I couldn’t access that kind of raw anger, not then and certainly not now. I wouldn’t want to. I wouldn’t know what to do with it. When it came to boxing, I fell in love with artistry, not power. I adored a boxing champion from my hometown, Donald Curry, who in my youth had more of my attention than Wayne Gretzky or Michael Jordan or Bo Jackson. Years later, I wrote a novel about a boxer, a man who also lacked rage but had world-class talent. The Hugo Hunter of my imagination was a winner but couldn’t scale the biggest heights. Like the very real Donald Curry, the fictional Hugo closed the book on his fighting life by leaving unrealized potential on the table. I find the stories of striving that comes up short so much more compelling than triumphant narratives, whether in real life or between the pages. If we haven’t approached the fullness of what we can be, and we still have time to work at it, that’s a reason to keep punching, right? “What I had was not a lack of passion. I had an abundance of human frailty. You want to tag me with that, go right ahead. Guilty. But don’t say I didn’t have heart.”—The Fallow Season of Hugo Hunter With more yesterdays behind me than tomorrows ahead, I think sometimes about what it felt like to be young and afraid and how transformative it was to be given something that took the fear away. Nostalgia is nice and all, but I hope I’m not someday prompted to rely on that muscle memory and square off. I can’t be sure the fight is still within me, and in any case, I’m old enough to be someone’s grandpa and should be done with such foolishness. Leave me alone and stay the hell off my lawn. On the other hand, as long as I’m on this side of the dirt, I’d like to have some vitality, because the air I breathe doesn’t taste as good without it. I don’t have to take the guy who lives across the street up to Knuckle Ridge and see who can hurt the other. That would be stupid and pointless, and I try to stay out of those areas as much as possible, unsuccessful though I sometimes am. I’m thinking here of lifelong learning, of having some kind of ongoing or shifting challenge, of keeping an eye on some beacon beyond myself that offers a reason for getting up each day beyond obligation and the allure of breakfast. Gary Barcroft taught me to throw a jab and a right cross and a left hook and an uppercut. They were good lessons for the time, for the kid I was, and for the man I was yet to become. Forty-plus years on, I feel most alive when I have something new to learn. Maybe that’s progress. Maybe that’s how I move from middle age into dotage with a modicum of grace and a manageable amount of frustration. I can see examples on both ends of the spectrum in the men I call father. My dad was born on the cusp of summer in 1939 and is sliding through the remainder of his days bewildered by what he sees from a world that has left him behind. A more accurate assessment would be that he left himself on the side of the road with a set of skills and interests that stopped expanding sometime around 1985. He’s stubbornly not online, except to the extent that I serve as a proxy. Computers confuse him. Phone trees enrage him. Betrayed by his failing eyes, he can no longer dabble in fixing things, in jury-rigging solutions, or in driving his truck (he no longer has a truck, nor a license) to a fishing hole. He sits and he waits for his next doctor’s appointment or our next backgammon game, and he’s astonished that he somehow made it this far and, distressingly, that he seems to keep going. He’s 81, and he comes across as so much older. My stepfather, a January 1942 baby, runs and reads. He builds websites and chases his grandchildren around the yard. His interests are wide. He’s always been that way, for as long as I’ve known him (going on 48 years now). At 78, almost 79, he seems two decades younger than my dad does. The difference isn’t rooted fully, or even mostly, in the physical condition. It’s in his willingness to engage mentally and emotionally with the world he occupies. Put more simply: One man has yielded to his fear, and the other keeps finding some fight. The lessons from both of them are mine to take. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

April 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed