|

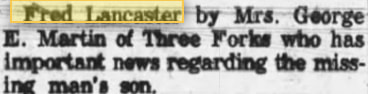

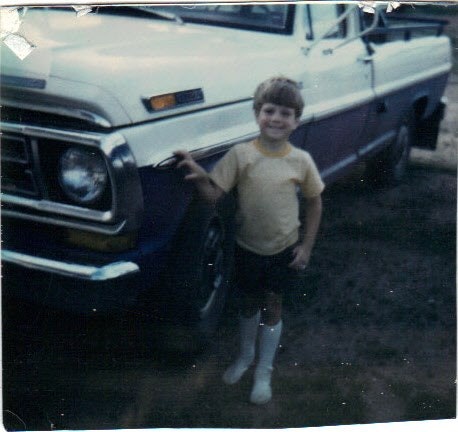

7/13/2021 0 Comments Down the Rabbit Hole …... and into the rest of the story, or at least more of it. I've been on the masthead of Montana Quarterly for the better part of a decade now. But back in 2010, when I had one novel to my name and not much else in the way of published literary work, I was just a guy pitching an essay to Megan Regnerus, then the magazine's editor and now our beloved editor emeritus. I called it The Small Things, and it was written after my father, Ron, and my Uncle Bob Witte (RIP) ventured out to the Fairfield Bench, near Great Falls, and found the dairy farm that shaped Dad's young life in some pretty horrible ways. I won't say much else here; you can read the piece for yourself, and I hope you will, because it provides a good anchoring for some discoveries I recently made while digging through archives. Long story short: I've always wondered about some of the details my father told me that day on the bench, not because I thought him dishonest about the general gist of things, but because he was 71 years old (he's 82 now), and that's a lot of time for the finer points to get lost. But he hadn't lost them. Not really. Let's dig in ... From the piece: "I’d heard, or maybe I’d assumed, that my paternal grandfather, Fred, had walked out on the family when Dad was two or three years old. But here was Bob, telling me that it had been a proper divorce and that Dad’s mother had rejected the children." The archives say ... Pretty much dead-on, if Fred's account of it is to be believed. He sought the divorce. He also tried to get the children (Dad, his older brother Duaine, his older sister Dolores). From the piece: "When Fred showed up to get Dad a week later, Dick locked the little boy in the basement and met Fred at the road. He carried a shotgun, all the better to send Fred on his way. Three children could accomplish a hell of a lot more work than two, and Dick aimed to keep Dad close, be it with a gun or a fist or a horse whip." The archives say ... Nothing I found speaks directly to this episode. Still, I'm not about to contradict Dad; he remembers it, he's shaken by it all these years later, and trauma has a way of imprinting itself immutably. What I know for sure is that Fred and Della and the man who became her new husband, Richard Mader, had confrontations. Here's the evidence: I've saved the best one for last. The remembrance of my father that was shrouded in the most mystery was where he went and what he did when he finally ran away from Richard Mader's dairy farm for good. Dad's memory is that he went to work for a farming family near Three Forks. I had no reason to disbelieve him, of course, but Three Forks is a fair distance from Fairfield. I wondered how he got there and whether he might have actually ended up somewhere else, somewhere closer, and just lost the place to the intervening years. Nope. From the piece: "After a few weeks, he ended up on a farm in Three Forks, doing odd jobs and being attended to by a kind family that kept him shielded from Dick, who was still looking for him. After a year or two, Dad told the farmer that he would like to see his father again, and the man agreed to find Fred and take Dad to him. A few weeks later, word came: Fred was in Butte. "More than fifty years later, Dad’s voice broke and his eyes floated in tears as he revealed what happened next. They were the only emotions he betrayed in telling the story. “'The farmer told me, "I’ll drive you to Butte and once you’re there, I’ll put you in a cab and follow you to your father’s house. Once I see that he’s come out to get you, I’m gone." ' "In a singular act, that Three Forks farmer, whose name has been lost to the intervening years, did for Dad what no one else could be troubled to do: He acted in the best interest of the child." The archives say ... Well, just have a look from a newspaper's "persons sought" column:  Dad, early 1960s. Dad, early 1960s. Getting at the details of my father's life has been a driving pursuit for many of my own days. Part of it is that I'm his only child, and if there's a story to be salvaged, it's up to me to mine it and tell it. And part of it is that I'm so heartbroken for the boy he once was, a clearly smart youngster who was denied so many of the blessings of his age, who was brutalized and stunted and who has persevered despite it all. I know how violence cycles from generation to generation, and I also know that the man I call Dad has refused to spin it on into me. It's the great achievement of his life, and he probably doesn't even know it. I want to drag the shit that happened to him into the light, the best disinfectant for what was visited upon him. He's not a hero. He is, in fact, a deeply flawed man (as is his son, as was his own father—there's more to that story, for another time). But he's my dad, and I love him. Addendum: There's an earlier piece, originally published by the San Jose Mercury News in 2004, that focuses more on finding out what became of Fred after Dad reunited with him in the mid-1950s. That was the last time father and son saw each other. Dad went into the Navy, and Fred went ... well, that's the interesting thing. You can read about that here.

0 Comments

7/7/2021 2 Comments A Gathering of FriendsJonathan Evison, one of the writers I most admire artistically and, even more important, as a human being, once said that each day he tries to do something for a fellow writer before he does anything to advance his own career. As a recipient of that kindness, I can say it's not idle talk. It's the way Johnny faces the world. It's an example that can be both learned from and emulated. In recent weeks, I've been teaching myself to make little promotional videos for books. (Look up "autodidact" in the dictionary, and there's my big, dumb face. Or should be, anyway.) For practice, and to put Johnny's ideals to practical use, I've been working up some videos for my writer friends, especially those who have recently released books. (I also did one for my wife, who deserves everything I can possibly give her.) Because here's the truth: We all need help getting out the word about the good work we've done. This is as true for the writer who gets the choicest pre-publication reviews and bookshelf space as it is for the writer whose book makes barely a ripple. (I've been both writers. I am both writers. I'm speaking truth here.) It's a lonely business, one that can be stingy with grace and validation amid seeming torrents of rejection and self-doubt. Please consider these books. I highly recommend each of them. If you love a book, consider buying it as a gift for someone else to love. Or tell someone. Leave a review. Reach out and tell the author. The words will be deeply appreciated. And thanks for reading! The Center of Everything | Jamie HarrisonBest Laid Plans | Gwen FlorioRegarding Willingness | Tom HarpoleCloudmaker | Malcolm BrooksThe Second First Time | Elisa LorelloAmerican Zion | Betsy Gaines Quammen6/20/2021 0 Comments We're Back! (Thank Goodness)

The fears and hesitations of the pandemic have been myriad—what if I get sick or die or can't work or, or, or…—and yet as I didn't get sick or die and kept right on working, the things I missed most, holed up in the house, were human and artistic. How I longed to go to a badass poetry reading. Or a play. Or a concert. Oh, how I took those things for granted before COVID-19, and oh how I never will again.

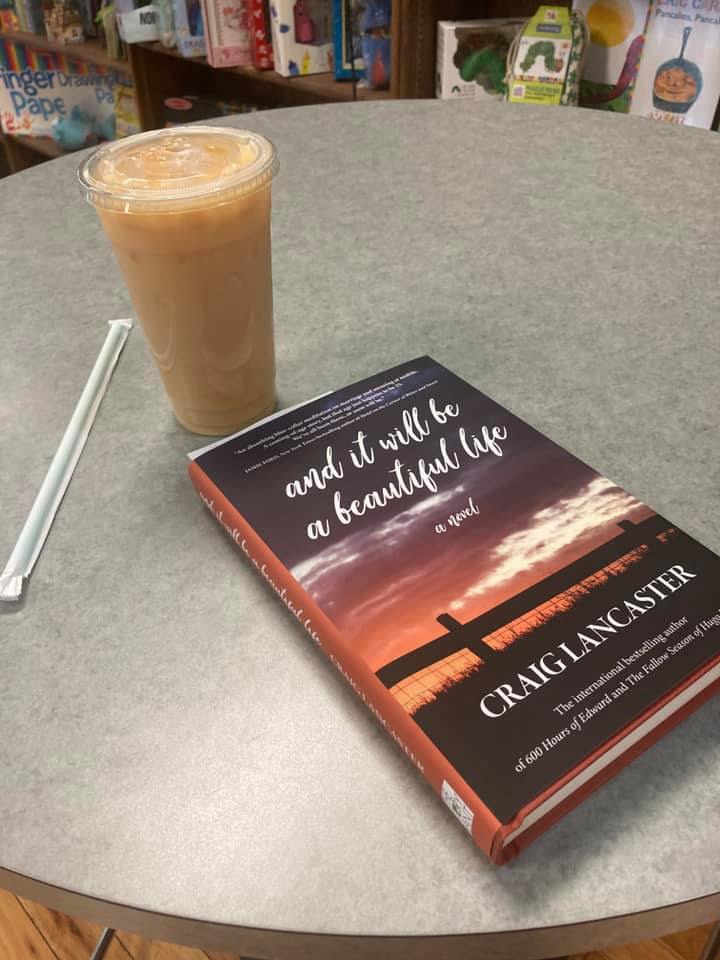

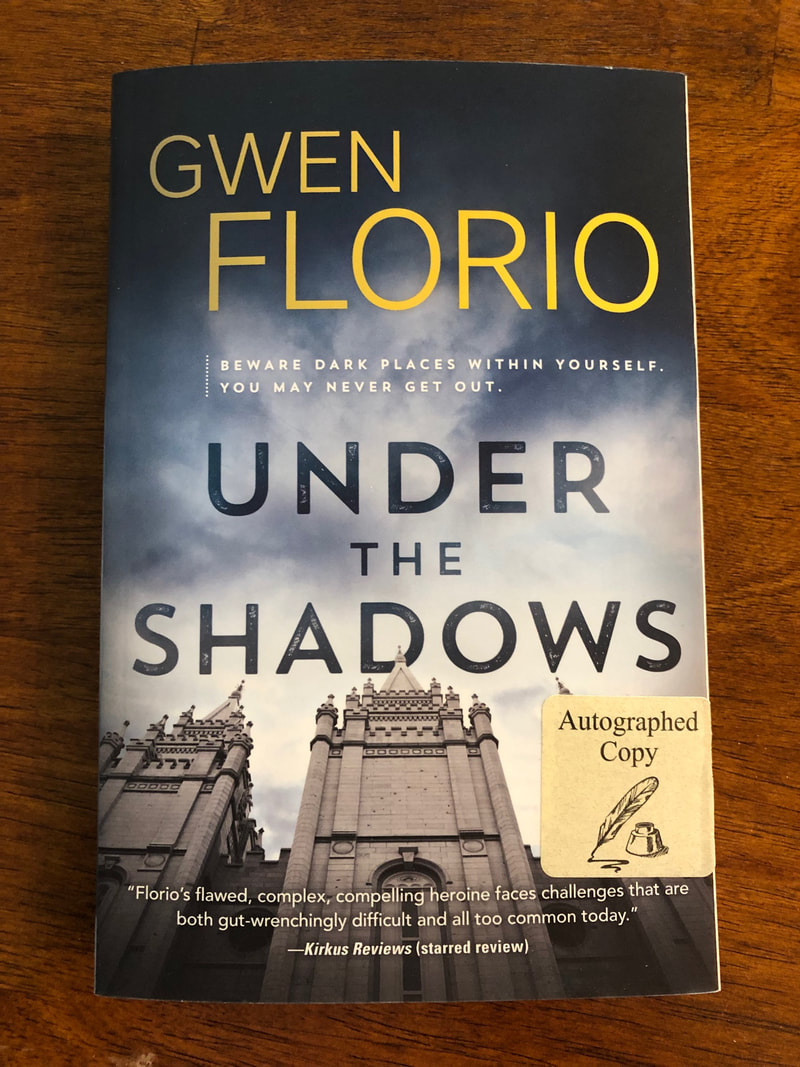

On June 19, about 10 days into the life of And It Will Be a Beautiful Life, we had a couple of events at This House of Books in Billings to mark its birth. What a day it was—the gift of fellowship, of seeing people I haven't seen in years*, of hugging necks and reading from this new work. I missed it so much. I think it's been at least two years since I've done it. And now, I can't wait to do it again. *--We moved back to Montana from Maine in April 2020. Right in the middle of the pandemic. There are people I love whom I haven't seen in these past 14 months, and some of them, at last, I saw at This House of Books. I tell you, I would have cried if I hadn't been so busy being grateful. 6/11/2021 0 Comments How to Spend a Day in Montana** — one of an endless number of permutations 9:50 a.m.: Head out of Billings due west with fair Elisa. Destination: Livingston, 117 miles down Interstate 90. There is much I could say about Livingston, although it would be nothing that hasn't been said before by better observers with keener insights. I made a friend laugh earlier today by calling it my Emergency Backup Montana Hometown. That's how I feel about it and the people I encounter there. (It was good to see you, Marc Beaudin. It's always good to see you.) 11:45 a.m.: Meet Kris King for lunch at Neptune's. In my early days of designing Montana Quarterly, Kris—one of the magazine's steady contributors (she does the author interview each issue)—gave me shelter on my overnights to Livingston for final magazine production. She's a whip-smart, offbeat, fun, funny, wonderful friend who has been extraordinarily kind to us, and it was the first time we'd seen her in more than three years. (We moved to Maine. We moved back. There was/is a pandemic.) If you've read my short story Remember Me in Istanbul, you might remember the ex-girlfriend's house that a guy and his wife let themselves into on a winter night. I modeled that house, and the spirit within it, on Kris' place. Now you know ... Around 12:40 p.m.: Head a few blocks over and get a sneak preview of the forthcoming Edd Enders Retrospective. (June 18-19 in Livingston, and you should totally go if you're within driving distance.) It's one magical thing to be able to stare deeply into a single Enders work, which we're fortunately able to do every morning, as one adorns our bedroom wall. (I mentioned Kris King and her kindnesses; the painting below is one, a wedding gift that we treasure.) It's quite another to see canvas upon canvas, crossing all eras of his wonderful work. What a thrill for us. Around 1:15 p.m.: Head out for Bozeman, another 26 miles west. We ended up at the Emerson Center, a place I'd often heard about but never visited. There, I dropped off a copy of And It Will Be a Beautiful Life to Rachel Hergett, one of Montana's premier writers about the arts. It was our first face-to-face meeting, another unfortunate byproduct of the pandemic. Can't wait to renew acquaintances again and again. I'm telling you, there was a buoyancy to the entire day in this regard. We're opening up, and hope is flooding in where darkness once settled. I'm allowing myself to dream of literary readings and concerts and sporting events and dinners with friends. Around 2:45 p.m.: Two more stops, both essential. First, Country Bookshelf, one of the finest bookstores you'll find anywhere. What a wonderful feeling to see the new book paired up in the window with Sweeney on the Rocks by Allen Morris Jones. Allen and I are doing a virtual event hosted by Country Bookshelf on June 30. We'd love to see you. And then to also see it on the shelves ... I also scored a Gwen Florio novel. Signed. Who's the lucky kid? Finally, no trip to Bozeman is complete without a stop at The Baxter and the little chocolate shop in the lobby, La Châtelaine. Elisa had the Hawaiian red salt caramel truffle. I had the French martini truffle (below). We split a Meyer lemon truffle. No regrets! After that? Eh, there's not much to report. Just a 143-mile drive through some of the most beautiful countryside there is, pulled along by the mighty, north-flowing Yellowstone River, a ribbon to guide us home. In the best iteration of myself, I try to be grateful for the life I have and the way I'm able to live it, but circumstance and the intrusion of transient difficulties sometimes get in the way. Perfectly natural, of course, but also something that can swallow your perspective if you let it.

Today was all gratitude all the time. For this life, for this place, for these friends, for these adventures, for the next bend in the highway ... 6/10/2021 0 Comments Some Distances Defy BridgesOriginally published March 11, 2021

My father and I were on our way to a vaccination clinic several weeks ago (1), which should have been a happy occasion, and yet tension and sharp words edged into matters, as they so often do. The clinic was close to both my house and the vet from which I’d ordered Dad’s allergy-ridden dog some food, so I laid out the plan: get our shots, drop my wife off at the house, go get his dog’s food, take him home. It should have been an unassailable itinerary but wasn’t. “Just take me home,” Dad said. “That way, you don’t have to run back and forth.” “No,” I said. “It’s a loop. And if I take you home, I’ve still gotta come back home, and you don’t get your dog food.” “I don’t need it today.” “But we’re almost there.” “OK, OK, Jesus.” And this, of course, is when my anger burned and, because I am not smart enough to hold my tongue, I let him have it: “You know, I actually have a brain, and I can actually use that brain to figure shit out.” Boom. Silence, the rest of the time we were together (2). I don’t want to hang too much on this one flare-up, except that it’s representative of almost every flare-up that ever preceded it and predictive of every conflagration yet to come. We’re two stubborn men who share a last name—but no blood (3)—and almost nothing else, except some deep-seated compulsion to love each other despite it all and to keep trying to hold together a relationship. I suppose, by that metric, we’ve done reasonably well. We’re fifty-one years in, and neither of us has cut the other loose. We’ve flirted with short-circuiting the thing a time or two, but we’ve never had a rupture we couldn’t eventually pick our way across. I’ve had the better part of my lifetime and his (4) to consider what the fundamental difference between us is, and while the flippant answer--everything—remains ever at the ready, I think the heart of it comes down to one basic thing. Reflection. That is, the essential quality of looking within to discover why you are the way you are, what experiences shaped you, how those experiences were viewed at the time and are viewed in hindsight, how they might inform the choices at the junctures yet unseen. Reflection is the currency by which I get through the world. A lot of what comes up into my face doesn’t make a lot of sense to me in the moment, particularly if I’m trying to suss out someone else’s angles or motivations. I’ve learned to trust hindsight and time to bring clarity to at least some of what initially seems inscrutable. Where I’m able, and when I sense that I won’t do more damage, I’m a big believer in closure, even if the loop that gets tied off rests solely within my own head. My momma taught me two things that have been invaluable to the flawed man I’ve grown into: I can say I’m wrong when it’s so, and I can say I’m sorry and mean it. My father has never shown me either of those two capabilities, and if he’s inclined toward reflection, he keeps those thoughts awfully close. They never travel from his head to his mouth, and thus they are at least twice removed from the ears of someone who could stand to hear them, someone who might reconsider much if he could get some help in understanding just a little. Here’s where our key difference, the factor at the root of every occasion when we get at loggerheads, tangles me up: Am I exercising a form of privilege when I put such value on reflection? My life is not like his. Nobody hassles me if I take the time to linger in my interior life (in fact, I could well argue that it’s a professional imperative). Dad’s growing up was fraught and dangerous, and it’s entirely possible that he doesn’t look behind him because so there’s so little back there he would want to see again. When I’m at my most frustrated with him, when he’s been withering in his criticism or his disdain, my wife often steps in to remind me: His whole life has been about survival. He doesn’t think about how the moments connect. He thinks about living to the next one, then the next one, then the next one. You can see it in his pantry, stocked to survive a nuclear winter, even though he eats like a bird these days. He keeps the wanting at bay. Do I have an obligation, then, to take him as I find him, to give him a pass for all that he is and all that he might well be incapable of being, and to do the heavy lifting required to meet him where he stands? Maybe. Then again, I could make a good case that I already do, and that whatever distances remain will be closed only by an equal effort from him. I’m his ride to where he needs to go. I’m his paperwork processor, the one who makes phone calls on his behalf, the reader of fine print, the sentry against scammers, the negotiator of byzantine governments and health care providers. I’m not a martyr to these things; they’re just duties I’ve picked up along the way, as first he aged and then he became elderly, as eyesight and health slowly fail him without robbing him, yet, of time altogether. I have one goal for him—a singular hope—and that’s to see him into the cosmos without pain or terror. And the scariest part of that duty is the possibility that my own health might falter before I can get him there. So we go on, he and I, to the next obligation, the next game of backgammon, the next time I’m utterly unable to explain to him who I am, what I value, where my aspirations lie, what I’ve learned along the way, and where I keep failing. Until the next time we bark at each other, then sift out the silence, then pick it up and try again. By the time you read this, our second shots will have been administered. He’s no doubt forgotten the last time we butted heads. Me? I’ve turned the memory into the hope that there won’t be a next time, or that I’ll find it within me to be a better man should it come. I wouldn’t lay favorable odds on either one. Endnotes (1) And so it was that I became aware of the phenomenon known as “vaccination envy.” Three things, OK? First, I’m 1B. Second, it was my time to be in line. Third, I would trade my chronic illness—never you mind what it is, unless you’re my doctor—for a spot deeper in line. In a friggin’ heartbeat I’d make that trade. Short version: Get off my ass. Longer version: Let’s celebrate every dose. I hope yours comes soon, if it hasn’t already. (2) I’m not saying there wasn’t a benefit. (3) I was adopted at birth. (4) He’ll be 82 this summer. He had a series of heart attacks at 53 that damn near killed him. Don’t think I’m not well aware of how close I am to how young he once was. Originally published January 12, 2021

In September 2019, my wife and I came to a decision we had been nearing at different speeds and while balancing factors that both aligned and diverged: We would put our house in Boothbay, Maine, up for sale and return to Billings, Montana, the city we had left in late May 2018. We’d had a short, but sufficient, tenure in Maine and found it wanting in terms of our day-to-day life. Or, perhaps, we were the lacking ones and simply didn’t have what it takes to live there contentedly. Whatever the case, after several months of disharmony prompted by a move that just hadn’t worked out, we stood on common ground: We would end the Maine portion of our life together and haul ourselves and our pets and our stuff (and my father and his dog) back to Montana. Let me cut to the chase here: It has been a good decision, the proper one. We are relieved to be back in the house in Montana that we couldn’t sell in the first half of 2018 (a house that now would be plucked up almost instantaneously for a price that would subsequently lock us out of the market; time is weird, and so are the unforeseen consequences of a pandemic). With so much in flux and uncertain—the arc of the coronavirus, when we might see loved ones again, the republic itself—we check in with each other from time to time: Is everything still good? Are we still OK with this decision we’ve made? The answers are yes, right down the line. Nonetheless, my thoughts often do wind back fifteen months to that decision, and to the subsequent six-month interregnum between the listing and what eventually followed: the purchase contract and the closing and the loadout. I ponder how freeing it was to simply commit to a course of action, how calm we were after the decision was made, how we never got over-eager or frustrated as we waited for a buyer to fall in love with our little Cape house. And how, in a quite unlikely and unexpected way, I made my peace with Maine on the long fadeout. This is about that last part, in particular. I wrote about this for the Boothbay Register while we were still in Maine, so here’s the TL;DR version: The adoption of our miniature dachshund, Fretless, was followed shortly by my doctor’s admonition that I was approaching fifty and needed to exercise a good bit more than I had been. His final words on the subject: “Make Maine your playground. Take that dog with you.” Never let it be said that I can’t obey orders. The Boothbay Region Land Trust is the steward for twenty-six preserves on the peninsula, and while Fretless and I didn’t get to all of them, we made frequent use of the ones nearest us. I fell deeply in love with this particular aspect of Maine, and while it alone was not enough to offset all of the factors compelling me (and us) back to Montana, the love was and is real and deep and true. Those coastal rivers are breathtaking. I was enchanted by how easily I could walk away from my car at a trailhead and disappear into a stillness and a silence that were not at all intimidating. I could hear my breath and my heartbeat and Fretless’ little steps in the woods. It hard-bonded us, making him my faithful companion and me his trusted doggie dad. At the outset of our relationship, we needed what those walks together gave us. It’s different now, here in our part of Montana. The most easily accessible trail in our neighborhood is a concrete suburban path we can walk out our door and join. Or I can pitch Fretless into the car and take a short drive to Lake Elmo State Park, where there’s a manmade reservoir featuring a perfectly adequate, perfectly flat trail looping around the water. The prescribed exercise is good, and Fretless has no complaints, but that slip into the silence of my own head doesn’t really happen here. There’s more sky than scenery, an inversion of the Maine experience, and we’re never far away from the sight of houses and the sound of cars and the scents of an encroaching small city. It’s not lesser, necessarily. Just … different. And when our walk is through, we return to the car and to our house and to the contentedness we’ve found here after nearly two years away. That part, certainly, is a considerable improvement. So what’s the difference here? Why was one place home and the other wasn’t, and why did we have to leave to find this out? As much as I wish I could, I don’t think I could tabulate it on a worksheet. So much of what works or doesn’t work in our lives—I’m talking jobs, relationships, what we do, where we go, where we live—comes down to timing and current circumstance. Once we learn to account for the variable of timing, it’s easier to let go of the things that don’t happen the way they might if we had full control—or any control—over the essential details. It also neutralizes the hard sells of commerce and the trafficking of romantic tropes. You learn to appreciate circumstantial convergences. You also learn to discount the notion of magic when timing can adequately carry the explanation. We moved to Maine and wanted to make it home. We had loved it from afar, and we had spent time there before the move, and we thought we and it would be a match. We were not. There were outside factors that augured against our really settling in. We’d had some income loss that was harder to replace there. My father, with whom I have a loving but often fraught relationship, came with us and moved into a basement apartment in the house we bought, and his presence in such proximity to us had a negative effect on the life we tried to live independent of him. We moved to a county that trended quite a bit older than we are, full of nice people who were insular and embedded into their own patterns. Maine was easy to move to and hard to become a part of, in our experience, but that, too, is a matter of timing. Does the picture come out differently if it had been just the two of us and we’d picked a house in Portland, where there are more people and more outlets for our interests? Perhaps. I don’t know. That time has passed. Or maybe it’s coming around and we just can’t see it yet. Or perhaps we’ll someday find a place we call home somewhere else. Long Island, where Elisa grew up. Texas, where I grew up. Virginia. North Carolina. North Dakota (that would be a surprise, but hey, whatever). Or perhaps, having taken our opportunity to return to Montana, we’re in the place where we’ll stay until we return to stardust. I would be more than OK with that. Time will tell. One way or another. A few weeks ago, as Fretless and I completed our lap around Lake Elmo, we approached a massive flock of Canada geese lazing on the shore. Fretless, the world’s most ironically named dog, one frightened of a melting pile of snow, strained just a little at the end of the leash, curious about these creatures he was encountering for the first time. He wasn’t threatening, yet the geese seemed to have a line, and we crossed it. They took briefly to the air in a mighty thumping of wings. They settled a few yards out in the water and scolded us for the intrusion. It wasn’t quite the majesty Fretless and I often enjoyed in the last place we lived. But it would be unseemly to be anything less than grateful for our chance to go there and take in a sliver of a much more complete picture. I made our apologies to the ruffled geese, and we walked the short distance to the car, and we loaded up. Five minutes later, we were home. 6/10/2021 0 Comments Darrin. Originally published January 7, 2021 There’s no clever way to start this, and from the vantage point of these scant words, I feel as though there’s only one place to end it: with anger. Which sucks. Darrin Marie Murdoch is dead. As I sit writing this—on Christmas Eve, for publication in a couple of weeks—she’s been dead for four months and ten days. I’ve known for the ten days. That’s it. And I’m pissed, mostly that Darrin was plucked from this life when she was so young and so loved and so needed (which I’ll get to soon), but partly because I didn’t know she was gone until a succession of thoughts came to me: 1. I haven’t seen updates from Darrin in a while. Facebook and its confounded algorithms are hiding her from me. 2. I’ll visit her page. 3. Oh, god, no. I could castigate myself for not seeing her obituary in the newspaper or online. I could lash out at our common friends who did know she was gone and didn’t tell me. (I could do it, but I would be wrong and I would be unkind.) I blame the pandemic. Not for taking her, because that doesn’t appear to be the case. She’d had a host of health difficulties and a recent surgery, and she went to sleep one night and didn’t wake up on the other side of it. This is life and the bargain that comes with it. You gulp in that first big breath, then you start playing your time against a clock that stops at some indeterminate hour. I get all that. What I don’t get, and what I’m continually angry about in a universal sense, is why it had to be this way. Those of us who have acted responsibly (and aren’t frontline health care professionals or essential workers) have gone into our silos for nine months and counting while the government fails all of us and while we fail each other with selfishness and a miscast notion that freedom can stand independent of responsibility. Our lives have gotten smaller, if indeed we’re fortunate enough to have hung on to them at all. In the house my wife and I share, we wake up, we have breakfast, we split up for work, we reconvene periodically throughout the day, we climb into bed, and we do it all again. We have each other and our pets, and that’s a lot, but it’s also not nearly enough. Meanwhile, in the larger sense of this country’s collective COVID-19 failure, we’re all losing what binds us even as we’re inured to the loss. It feels as though, on the other side of this, we owe each other forgiveness for the things we have and haven’t said and the things both done and undone. I feel the weight of the penance I need to do, the amends I must make, and the grace I need to offer. I also feel the burden of anger that lights up and burns like flash paper. How does anyone balance all of that? In April, just a couple of weeks after we arrived back in Montana after a nearly two-year sojourn in Maine, I wrote these words for an anthology called Stop the World: Snapshots from a Pandemic. They felt visceral then. They feel something else now, in retrospect—hopeless even as the vaccines roll out (amid one final failure from the outgoing administration), sadly outdated in the death toll, and prescient in a way I never wanted to be: We’re alive, if not entirely living as we once thought of it, while we wait for something resembling normalcy to return. As I put down these words, the U.S. death toll has crossed 50,000, a number surely to rise. Only in the awful solitude of my imagination do I dare consider what it might be before these words find your eyes. I don’t want to know. But I’m going to. If I live to see the final toll. If I’m lucky. The word lucky has never been so perverse. If you’ll forgive the coldly corporate nomenclature, COVID-19 has a cost structure, and the tolls seem random: Some pay with isolation. Some pay with inconvenience. Some pay with sickness followed by recovery. Many millions have paid with their jobs. Tens of thousands, so far, have paid with their lives in the U.S. Worldwide, it’s hundreds of thousands more. The only bitterly sure thing is that we’re all paying with something. I was supposed to see Darrin again. Surely, in a normal set of circumstances, I’d have seen her between April and August. Failing that, surely, in a time unencumbered by social distancing and voluntary withdrawal, I’d have been engaged with our shared social structure enough to know she had gone. I would have been at her funeral. I would have hugged her mother, who has lost all of her children these past few years. I would have said goodbye instead of oh, god, I didn’t even know you were gone. This is part of the toll. Darrin was a teacher*. She loved those children with her whole heart. She especially loved the poorest of them, the most neglected, the ones with the biggest hurdles to overcome at the youngest ages. She believed in them, and for that reason more than any other, she should have lived forever. She was also fun, and smart, and bawdy, and loud, and loved. Every time she saw me--every time—I got a chaste kiss on the cheek. For several years, I had a standing invitation to her book club’s Christmas party, an annual date I hope will be renewed when we can gather again, although in the next beat I wonder how it can go on without her. Nobody loved the food or the drink more than she did. Nobody was more willing to say what she really thought of that month’s book than she was. (I know this firsthand, having a memory of this exchange: “Listen, your last book didn’t have an ending.” “Yeah, it did.” “Craig, no, it didn’t.”) Goddammit. I should have had time to tell her she was right about that. *If, like me, you believe that public schools and public education are worth fighting for, and that teachers like Darrin Murdoch stand between the rest of us and the wolves at the door, I implore you to offer a gift to the Education Foundation for Billings Public Schools in the name of Darrin Marie Murdoch. Thank you for considering it. Originally published November 20, 2020

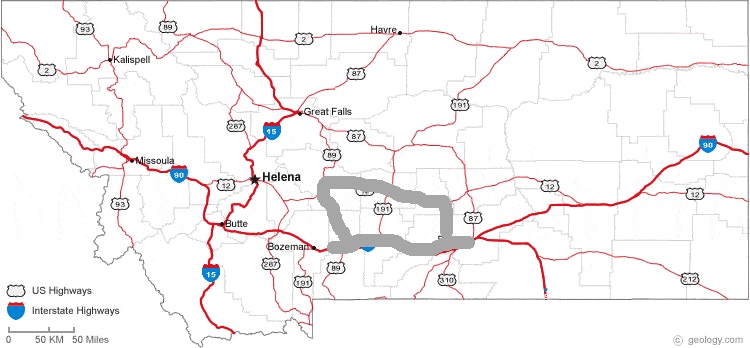

I knew the anxiety was coming before it made a full reveal of itself, when it was lurking several levels below the surface, before my toes began tapping, before my fingers started clenching and unclenching, before my attention started doing walkabouts in the middle of essential tasks. I knew what it was about. I knew what it wanted from me. I’m a restless man, which I grew into after being a restless boy and before that a restless baby. There’s a story that predates any of my memories, one told by my mother. She apparently went to my doctor and said, essentially, what gives with this kid? He stays up late. He doesn’t sleep through the night. Is this normal? And the doctor chuckled and said, well, there is no normal. If it affects his development, it’ll be something to address. If not, not. Well, here I am, fifty years on. We can have a debate sometime about how the whole development thing went, but this much is undeniable: I’m restless. In my work, in my relationships, in my interests, in my physical position on this earth. The coming anxiety was about that last bit. I needed to go somewhere. Our pandemic year makes the particulars of going decidedly more complicated than they were in the Before Times. Who’s going with you? Where? Who are you going to see there? You’re not going to eat indoors, are you? My answers, right down the line: My dog. Livingston, Montana, and points beyond and between. A couple of people. Fuck no. I told my wife on a Monday that I wanted to do it. No, that I needed to do it. On the subsequent Thursday, I did it. We did it, Fretless and me. It was about time. We’ve been back in Montana for a little more than seven months, Elisa and me and Fretless and Spatz the cat. We left Maine and our abbreviated experiment of living there as COVID-19 flared on the East Coast and the byways between Maine and Montana largely emptied out. We got a household and the contents of our lives moved not just once but twice—first into a temporary condo while we waited for the renters to leave the house we still owned here in Billings, second into the house. Through it all, we kept our heads low and ourselves relatively safe, even as the infections rose with ferocity in our old town that had turned new again. We formulated and ditched plans. No, we wouldn’t meet my folks in Denver. Too dangerous. No, I wouldn’t drive to Texas alone to see them. Too much of a time investment, and too dangerous. No, Elisa wouldn’t fly back East to see her mom and siblings. Too expensive, too much quarantining on both ends, too dangerous. It’s been mostly OK. I’ve been blessed with plenty to do, having a full-time job that was already conducted from home before the rest of the country discovered it out of necessity. Freelance jobs come my way—as many as I need and not more than I want. I’ve had a couple of pipeline inspection gigs—did I mention that I’m restless in the ways of work?—that I could drive to. We’ve been more fortunate than many. Our sacrifices—not seeing friends, not traveling at will, keeping our distance, wearing a mask—have been reasonable and not at all onerous. It would be errant of me to suggest otherwise. And yet … When you’re kinetic, a word that sounds so much better than restless, you sometimes have to go. I settled on Livingston for three reasons: 1. I can get there from here. 2. Of all the wonderful towns in Montana, Livingston is the closest thing to a second hometown to me. It’s the place from which one of my side gigs, as design director of Montana Quarterly, emanates. (I have mentioned the whole restless-in-work thing, right? Just checking.) There are friendly faces in downtown shops and on side streets and at restaurants, or at least there were when you could go to such places. 3. Parks Reece wanted an old wasps’ nest I cut down from one of my trees this fall, and he was willing to give me some of his art in exchange. Parks, in so many ways, is the perfect embodiment of the quality that has made Montana my home even though I didn’t grow up here, and a perfect illustration of what I hoped to find in Maine and did not, which compelled my return. I didn’t meet him on my own. He became part of my circle of friends because others, most notably my boss at the Quarterly, Scott McMillion, drew me into theirs. Think of the old trick with the chalices stacked in a pyramid, with wine filling the uppermost cup and cascading down until all of them are brimming. In nearly a decade and a half of living in Montana, this is what it’s been for me—I’ve made friends who’ve had friends who’ve become my friends. They fill my cup. I hope I fill theirs. I try. At Parks’ gallery, while Fretless alternately hid between my feet and ventured halting approaches to as many new people as he’s met in his short lifetime, we talked about this, what I’d looked for in Maine and hadn’t uncovered. Though I found the people there nice enough, there came a juncture where niceties ended and more intimate friendships were harder to penetrate. There’s very much a “from away” label that gets put on people who haven’t been in Maine for generations upon generations. It happens in Montana, too, but there’s often some dynamic tension to it. For one thing, if you’re a fifth-generation Montanan and you have some sense beyond yourself, you have to give some consideration to the idea that you and your people have been stealing what belongs to someone else for a long time. For another, there’s a welcoming nature I’ve found here that I didn’t find there. From the get-go with Montana, I’ve been comfortable with positioning myself as an outsider who found his way inside. I can’t claim it as heart earth. I can claim it as a found home. That didn’t happen in Maine, and it became increasingly clear that it wouldn’t happen in Maine. None of this is empirical, by the way, and I don’t want to end up in the weeds of who or where is more welcoming and why. This is merely my own experience, informed by who I was and when it was that I encountered each place. And that, I’m well aware, counts only so far as I allow myself to follow it. And, really, it’s not remotely my point here. Let’s move on. McMillion and I grabbed a couple of sandwiches and took them to Sacajawea Park, along the Yellowstone River, and had a socially distanced meal at a picnic table. Fretless got his first-ever scraps of people food, little chunks of bread tossed to him by Scott, and while I’ve been steadfast about not letting him become habituated to such delights, I had to relent. If I deserved a treat, so did he. The rapport Scott and I have is a solid and satisfying adult friendship, one I treasure and one that is built out of a few tentpole commonalities and a nice smattering of differences. He’s a hardcore outdoorsman, a hunter and a fisherman and a guy who knows his way around a canoe. I…am not. Scott likes to disappear into the backcountry or onto the vast prairie or down some stream. I think I’d like to rent an RV and park it in the shadow of a mountain, especially if the RV has a satellite dish and I can tune in a ballgame. We’re both big guys, mostly nonviolent, and as such we’ve had separate but similar instances of being drawn into physical confrontations that we’d have rather avoided in favor of a good book. He’s learned in the ways and the history and the art and the literature of his home state. I’m learned in the ways that get his magazine into print. We’re a good team, and we have some good laughs. After lunch, we walked along the Yellowstone River, giving Fretless a chance to stretch his stubby little legs, and we swapped stories of long-ago youthful indiscretions and more pressing contemporary concerns. Before Fretless and I left, I told him I was going to take the long way home, around the Crazy Mountains and up through White Sulphur Springs and Harlowton and on home to Billings. He said that sounded dandy. He probably didn’t remember the last time I’d taken that route. I sure as hell did. When I plotted the trip with Fretless, I didn’t think of just how microcosmic it would be of the total Montana topographical experience, but it really was: In a day’s driving, interrupted by several stops, I saw mountains and river valleys and glaciated plains and bald, flattop buttes and fallow fields. I drove through sunshine and rain and flurrying snow. I drove on dry asphalt and on icy patches where the sun doesn’t alight. I had a whole year in a single day in Montana. I find the mountains and the rivers easy enough to appreciate and admire. You have to work harder to love the prairie or the badlands or a flat stretch where the wind blows so hard that it threatens to knock you down. I’ve learned to express my unabashed ardor for that Montana, the one that generally doesn’t end up on postcards. I live in the eastern half of the state, where the land and the life are harsher and drier and more emptied out. I’ve spent a good chunk of my life now on that side of the state. There’s a depth of field to an endless horizon, and a clarity of thought you can find in pondering it. I missed that while in Maine, too, and hungered to come back to it. It’s become a part of me in unexpected ways. On Highway 89, in White Sulphur Springs, I took note of the little park I’d pulled into on an October day in 2014, when Elisa had been on the other end of my phone, trying to talk me out of a dark hole I’d crawled into. She wasn’t my wife then, just a friend who knew I was hurting, punctured by the twin disasters of an unfurling divorce and an ill-advised rebound romance that was doing what such things do. It was bouncing all over the damned place, battering me with each reverberation. My friend, on the East Coast, told me to hang in, that it would get better, that she didn’t much like to fly but she would get on a plane and see me through it if I needed her to. I told her no. She could sense the turmoil. She couldn’t see the whirlpool. I didn’t want her getting near it. I don’t want to overstate this or minimize what it is to be in true psychological danger. That day, that moment, I think I was in peril. I’d had a cup of coffee with McMillion in Livingston, and he’d talked me through some of the turmoil. He suggested I go back by circumnavigating the Crazies. Spend some time, he said. Let rationality have a go at me. Irrationality got there first. As I drove deeper into Montana, I thought more and more about pulling the car over, parking it, and setting out on foot. That’s when Elisa called. She told me to go to the next town and park and call her back. So that’s what I did. The particulars? I’ll hold tight to those. I’m here. She’s here. The stuff that hurt then doesn’t hurt now. Time and tide, man. White Sulphur looked the same but different today. For one thing, a different man drove into it, in a different year, in a different car, with a sweet puppy in the passenger seat rather than a festering bag of worry and regret. Upon driving into town, I had my mind not on my own pain but on the life of the great writer Ivan Doig, who grew up in White Sulphur and who drew on its impressions for a lifetime’s worth of work. I wondered what it was here that burned into his memory and stoked his imagination. I know a little something about the overdeveloped interior life of a writer; I, too, am afflicted. I never met the man, though I badly wanted to. I would have enjoyed talking about that with him. I read him voraciously starting at age nineteen, and his books were like guideposts into what I wanted to do and to be, even though I ended up treading different literary ground. The longer I do this—and by this, I mean go through this life, although I could just as easily mean attempting to distill the complexities of human life into a story that has a beginning and an end—the more I have to acknowledge that memory is at the thrumming center of damn near everything. It holds out caution. It transmogrifies into inspiration. It informs choice. It drives perspective. As I turned east on Highway 12 and headed into the homeward portion of the drive, memories came at me like bolt-action rifle shots. Here in late 2020, I ran headlong into midyear 2006, when I’d resigned from my job in California and planned a move to Montana with a sort of half-baked plan for a writing life. First, though, I had a trip that had long been on the books, hooking up with my father down in Albuquerque and driving, just the two of us, up to Great Falls, Montana, the part of the state he was from. It seems almost absurd now, as he’s still taking in oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide, but there was an elegiac tinge to that trip when we undertook it. His health had been not so good, and we wondered, or at least I wondered, how many chances we would get. With Fretless, I was driving east on Highway 12. In June 2006, Dad and I were driving west. In November 2020, I kept looking around for touchstones of memory, and I found them in the straightaways and in the rock formations that looked like stacked waffle cookies and in the river that alternately hugs the bends in the highway and rambles off into the distance. I fixated on one particular memory of that long-ago year, of seeing a rusting backhoe on the south side of the highway, stilled and silent and abandoned. In subsequent years, after my initial move to Montana, I would have occasion to go up to Great Falls, and I would spot that backhoe every time and recall the first time I saw it, and I would wonder why it had ever been put there and, more pressing, why it had been left to time and the elements. And brother, if you want to know where a spark of fiction comes from, consider the extrapolations you can make from that starting point. A forgotten backhoe beyond some fenceline. When? Who? What? Why? I looked for that piece of machinery today, in the dying light and amid the snoring chorus of my worn-out pup. It didn’t show. I might have missed it. The relentless vegetation might have overtaken it. Whoever left it there might have come for it at last. Who knows? At the junction with Highway 3, I bore right, Acton just ahead, Billings forty-some miles in the distance. Fretless stirred, activated and attenuated and bouncy, a dog who really should switch to decaf. I snapped one last picture, of the big sky that was over me and over the one who was waiting at home for me. I got on with getting there. The restlessness often gets what it comes for. Sometimes, I do, too. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

April 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed