|

5/15/2023 1 Comment Dan GenselFriendships are funny things. Sometimes, they exist in a fixed place and time, sturdy and strong for a particular period in our lives. A counselor of mine, Jane Estelle, once told me that human relationships are often like cab rides. They have beginnings and ends. That was wise. It's true. Sometimes, though, friendships are a ride that never ends. You don't reach a station and get out of the car. You keep going, through years and locales and jobs and other relationships and seasons of your life. And sometimes they are both. They are fixed in time and endless. Those are the best friendships. Dan Gensel was that kind of friend to me. Dan Gensel is gone. I moved to Kenai, Alaska, in November of 1991. I was 21 years old, and I didn't know anybody there. I'd come from my hometown, North Richland Hills, Texas, and had taken a job as the sports editor at the Peninsula Clarion newspaper. Why? Why not? I was 21 and unencumbered. Alaska was far away. I wanted to go and could go, and that's a combination I wasn't always going to be able to put together. Now, for example. Couldn't do it. Won't do it. Want-to isn't even a factor. Years ago, I wrote a piece for the radio program Reflections West about that time in my life and the factors compelling me to move north. You can listen to it here. My first week in Alaska, I covered a Kenai Central High School-Soldotna High School girls basketball game. It featured two of the best players in the state, two of the best players in the history of the state: Stacia Rustad of Kenai and Molly Tuter of Soldotna. On one sideline was Coach Craig Jung of Kenai, a man I'd come to greatly admire in my brief time there. On the other sideline was Coach Dan Gensel. He and Craig were great friends and ardent competitors. Stacia and Kenai were coming off a state championship; Molly and Soldotna would win one a year later. I didn't know any of that. I was just a new-in-town sportswriter, trying to figure things out. The photo above, of Dan and Melissa Smith, one of the kids I covered that season, isn't from the game in question, but it's a good approximation of the Dan Gensel of my memories. After the game, which Kenai won, he sat in the bleachers with me and just talked. Where you from? How'd you come to this job? What's your background? Getting-to-know-you stuff. I liked him, right from the start. Later, I met his wife, Kathy, and his daughter, Andrea, and liked them, too. In time, it became love. But it was like, from the get-go. Those were lonely days for me, 4,000 miles from home, alone, barely scraping by, driving an on-the-verge Ford Escort and living in a one-room apartment. Dan and Kathy took me out for my 22nd birthday, just a few months later. Dan gave me seats on school buses to far-flung tournaments and let me sleep on his hotel room floor sometimes when that was the difference between my being able to cover something and not. He also gave me a basketball education, one I tucked away, then unveiled when I wrote a short story about a wunderkind basketball player and a coach and a town that loses all sense of proportion. Here's an excerpt from Somebody Has to Lose: “Mendy, it’s like this.” He squared up to the basket, squeezing the ball between his hands and planting a pivot foot. “First option: jump shot.” Into the air he went, releasing the ball at the peak of his jump and watching it backspin softly into the net. Cash, her face red, gathered the ball and rifled it back to him. “Second option: drive.” Paul took two dribbles into the lane and then fell back to his spot on the periphery. “Third option: make the next pass.” He slung the ball to Victoria Ford, directly to his left on the wing. “You know better than to just throw the ball over without even looking.” Paul turned to the players clumped on the sideline. “Shoot, drive, pass. When you get the ball in this offense, that’s the sequence. I don’t want anybody not following it, you got that?” Yes, sir,” the girls answered glumly. "You get the ball. If the defender has collapsed into the middle, you shoot the open shot. If they’re crowding you, drive around them. If you’re covered, make the next pass. This is not difficult. Run it again.” That right there, in just a few paragraphs, is the Dan Gensel philosophy of basketball. It inverts the conventional wisdom of the time—pass first, shoot later—into a kinetic, high-scoring, fun way of playing. And, man, was he ever successful. Won a lot of games. Won a state championship. Made the hall of fame. But that's not what I remember most about him. I remember that he and Kathy and Andrea became family, particularly after I came back to Alaska in 1995 for a three-plus-year stint at the Anchorage Daily News. I remember that I was a regular guest on their downstairs couch, so much so that it developed an imprint of me. I remember that they tolerated movie nights when I'd make them watch Ed Wood and Pulp Fiction, fare that was decidedly not up their alley. I remember later visits in California and Las Vegas. I remember Andrea's wedding in the early aughts down in San Diego, when Dan asked me to give the speech before the father's speech. Predictably, I went for funny and warm, extolling my love for a family and a young woman I'd watched grow up. Dan, after me, had everybody in tears with his love for his little girl. Later, in a quiet moment between us, Dan said, "I knew you'd take them one way and I'd bring them back the other." Teamwork, baby. I remember Dan's closing out the wedding reception by climbing atop a table and lip-synching "Don't Stop Believing." I hate that song, but I love that man. I remember, a few years later, Dan's serving as the best man at my first wedding. The marriage didn't last. The friendship endured. I remember all the times we talked about getting together over the past decade or so. I remember that we didn't make it happen. That'll be the only thing I regret. It's like I said: It's a friendship fixed in time and eternal. I'll carry it now, for however long I'm around. There's been a lot of that these past few years. Too much.  It's been a long while since Dan was a basketball coach. In his final years, he was a sports radio guy--a damned good one—and a grandpa, a role he made his own in an inimitable way. He and Kathy became community stalwarts in Soldotna. Andrea and her husband, Lee, are right there. It's been a good life. It will continue to be a good life, I'm sure, but those who love Dan will have to live with a big hole in it. It's a testament to the community Dan helped me build thirty-odd years ago that one of his former players, someone with whom I've been close since I was a 21-year-old green sportswriter riding a school bus, contacted me with the news. I spent just six months in that job at the Peninsula Clarion. My Facebook page is full of people I knew then and still know now, and I'm a lucky boy, indeed. Dan was 34 when I met him and 66 when he died, and that's both a long time and not nearly enough of it. I'll miss him.

1 Comment

2/24/2023 4 Comments The Best That You Can Do*

* Not just the words to a Christopher Cross/Burt Bacharach/Carole Bayer Sager/Peter Allen song.

Sorry. I had to.

Wait, strike that. I'm not sorry.  Tiffany Yates Martin, a book editor who also writes under the name Phoebe Fox. (FoxPrint Editorial) Tiffany Yates Martin, a book editor who also writes under the name Phoebe Fox. (FoxPrint Editorial)

The possible mechanical aspects of the writing life—what to write, when to write, what time to write, how much to write, etc.—are so many and so varied that I've discovered I can disagree with just about anything, given the opportunity to formulate a contrary opinion or just to wake up in a mood.

But once in a while, something crosses my desk or screen that inspires nothing but rabid agreement in me. My friend Tiffany Yates Martin—in fairness, my wife's editor on several projects, but I joined the two of them for a memorable and hilarious lunch in Austin, so I'm claiming her—wrote just such a piece earlier this week. You can read it for yourself, but here are just a couple of the stellar observations: I think there’s danger in talking about our writing in a diminishing way. Most obviously it sends us the message that our creative work isn’t that important or worthwhile. It’s just a lark, a silly little whim we pursue, but we’re not kidding ourselves that we can stand beside the actual greats of literature. And ... That means having a clear-eyed view of your work and where there may be room for improvement and growth, while also allowing yourself to be proud of its merits and strengths. Without that how can we hope to improve as artists, any more than a child who is given nothing but criticism and disapproval can develop a healthy self-image and flourish? We have to create a safe space for ourselves as artists where we have permission to fail, permission to grow. Seriously, if you are one of those "oh, I just write [whatever]" or "I just dabble" writers, go read Tiffany's piece and see if, perhaps, there's a way to recast your thinking into something that's realistic and celebratory. You create things. You conjure stories and experiences. You're awesome. Never forget it.

Years ago, after my second novel, The Summer Son, came out, it landed reviews in two regional publications that I fervently hoped would shower it with praise. I was riding high, at least from a critical standpoint, having seen my debut, 600 Hours of Edward, receive wide praise and some nice awards. I thought I'd written an even better book with The Summer Son, so I readied myself for an onslaught of plaudits.

The novel went 0-for-2 in redeeming those hopes. The review in New West was generally complimentary but cast the book as falling short of its predecessor. The review in the Missoula Independent was more of a split-personality assessment—which, interestingly, is what the reviewer accused my book of having—with effusive praise for the character development and something bordering on ridicule for the plotting. I know what my reaction was, in both cases: something deeper than disappointment and a bit short of despondency. (I suppose I'm blessed/cursed by not really giving a damn what you think of me, but I get a little bruised when my work isn't seen favorably.) It was fascinating to see reactions from my friends and colleagues. A couple called me to make sure I was OK. One told me the Independent piece was an unqualified great review, a point of view I had a little trouble accessing. (Her point, I believe, is that character development is the gold standard of literary work, and I'd won the critic over with that part of my effort. OK, then.) The point of all this isn't to indulge in ancient grudges, although if I were so inclined, I'd point out that both New West and the Independent are dead and The Summer Son still puts money in my pocket every month, so chomp on that, fellas. But I am not so inclined. The fact is, the literary life of the West is poorer for those publications' absence, no matter how wrong they were on occasion. (OK, maybe just a little jab.) No, seriously, my point is this, and it's one I've made again and again: If you want something you can influence with regard to your work, better to forget how it'll be received, whether it will sell, if it'll make you rich, and put all of your attention on doing the absolute best work you're capable of undertaking at the time you undertake it. If you do that, if you're certain it's the best that you can do, you will owe no one anything. You will owe only yourself, and only this: growth, the gumption to try even harder the next time, a willingness to stretch yourself beyond what you think is possible. Some years after those reviews, I was talking with the guy who wrote the one for New West, a good friend of mine and a damn fine writer, and told him he'd certainly been right about certain things. I'd grown. I could see flaws I didn't see at the time I wrote it. I said something like "if I could do it over again, I would." And he set me straight: "Don't ever say that about your own work. Don't ever put it down." Absolutely right. You made that. Love it for what it is. Save "I should have done better" for next time, then do it. 2/19/2023 4 Comments Compromising with the ClockI'm more than a month into my new full-time job--more on that here—and have settled into a rhythm that both suits and serves me. This weekend has been the first time in that month-plus that I've been able to turn my attention to my current manuscript, which makes it, perhaps, a longer absence than I anticipated. But, hey, career changes are big deals. My focus has been in the right place. The biggest change, aside from the parameters of the job, has been to my sleep schedule. I've spent the preponderance of a career as a swing-shifter—4 or 5 p.m. to midnight or 1 a.m. In my younger days, I embraced the full inversion of that schedule. I'd come home, make dinner, fire up the TV, talk on the phone, whatever, then go to bed around 5 a.m. or 6 a.m. Wake up after noon, eat breakfast, head off to work. Lather, rinse, repeat. Later on, I realized how much of the day was getting away from me that way and adjusted. Home, directly to bed, wake up at 7 a.m. or so, have hours and hours to my own devices before I headed to work. I wrote a lot of novels that way. Back in January, my thinking was along these lines: I'll wake up at 5:45 a.m., write, eat breakfast, then start my workday.  It hasn't worked out that way. Oh, I'm waking up early. And I'm answering email, paying bills, doing whatever can be done when much of the world is asleep, then reporting to duty in my sweet home office. (Seriously, my office is the BEST. I'm sitting here at the short end of the L-shaped desk, writing this as a warmup to today's work on the manuscript, and listening to the Flying Burrito Brothers on vinyl. You tell me how life could possibly be better. I dare you.) When I get off work in the early evening, I'm too fried to write. I eat, I visit my dad, I tend to small errands, then I trudge upstairs for another go-round with Mr. Sandman. Can't write in the morning, so what to do? Easy. Write on weekends. I have no absence of motivation to do so, and no absence of weekends to put those writing hours into. Point is, I can write a lot of novels this way, too.  The whole thing puts me in mind of a meme I shared on Facebook this past week, one that got a lot of traction with my artist-heavy social group. And it's something, perhaps, I don't focus on enough when I'm putting my hopes on this book or that book to connect widely and to ratchet down the financial pressures of daily American life. I don't do it for money. And I say that in a non-starry-eyed way, and in a way that's not too idealistic for my own good. The point is that being compelled toward the arts comes from a deeper place, a deeper need to make sense of the world and to contribute something to it that doesn't traffic in cynicism and power. Do I wish I had a better nose for generating straight cash, or that maybe I'd made different decisions along the way that would have augured more to the benefit of my bottom line? Sure. Absolutely I do. But I'm not dead yet. There's still time. Once I started getting comfortable with the multiplicity of ways I can define myself, it released me to embrace my multitudes. I can be an analyst and a content specialist. I can be a friend and a husband. I can be a brother and a son and an uncle. And, damn right, I can be an artist on my terms, in my time, trying to make a contribution from my cozy little office with a turntable and a drink fridge. I not only can but also am gonna. Just watch me. 1/15/2023 0 Comments Memory + Imagination = Fiction Elisa and I took our new presentation, title above, out for its first spin Saturday at the Stillwater County Library in Columbus, Montana. (Cool side note: The centerpiece pictured here was on our table at Grand Fortune, a Chinese restaurant in Columbus that we hit before the event. I can definitely say that's a career first for me. For Elisa, too.) To say that we were thrilled with the response to our program would be, perhaps, to diminish the meaning of "thrilled." We had a group of about 20 people who dug in with us, asked excellent questions and provided terrific insights, and even gamely took on a writing exercise at the end. The idea was to take The Word—the go-to warmup exercise I've written about from time to time—and apply the principles of memory harvesting to create the short fictional work that resulted. So we had the folks give us a passel of words, then we ran a random-number generator to choose one that would apply to everyone's work. That word: hayloft. Elisa and I wrote along with everyone else. I had the advantage of my laptop, so I was able to write about 630 words in the 20 minutes of the exercise. As I told everybody afterward, if the current manuscript took on words that quickly, I'd be done with it back in November. Of 2020. What follows is my effort ... HayloftMom told me I would be sorry if I didn’t go, if I didn’t see where my grandfather, her father, had grown up. I was dubious, to say the least. I liked our hotel, I liked the pool—the pool was about the only thing that made southwestern Minnesota in summer bearable to me—and I wanted to stay. She insisted that I go. I was nine. Guess who won that debate? The whole way over, our 1978 Chevy Citation baking on the blacktop, Mom told me that she’d only been here once, long, long ago, when she was a little girl, after grandpa had come back from the war in Italy. “It was like a magical place, Jeff,” she said, and I sat there thinking she should see some better magic. “Tractors. Gardens. Corn you can eat off the stalk. A hayloft, Jeff, with a tire swing. You can launch yourself clear into the rafters and come down in a soft landing.” I harumphed. Something good was on TV, and I was missing it. We made a little turn off the two-laner and went down this rutted two-track, between two fields of corn headed for silage. I wasn’t going to be eating anything off these stalks, I figured, but seeing as how I was a civilized boy, I didn’t need anything that didn’t come in a can anyway. But maybe I could slop the hogs and shovel out the chicken coop. Boy, howdy. At the end of the lane stood my grandfather, all unfolded six-foot-six of him, encased like a sausage in denim overalls and a gingham workshirt. I’d never seen him looking like that before; the guy was a navigator for Alaska Airlines, not a goat roper, but I guess it was the same nostalgia trip for him that it was for Mom, making his way to the place where he’d grown up. Beside him, another couple—that’d be great Uncle Leo and great Aunt Darlaine, I supposed, the proprietors now of the farm. I’d never met them, I didn’t think. Mom started crying once they came into view, and I shrank down in the seat, both because they were all waving stupidly at us and because Mom cried a lot that summer, and it had become clear I couldn’t do much other than let her hug my neck. We got out. Grandpa came at us, and Mom collapsed into him, crying at a stronger pitch. He folded her in like the bear of a man he was, and he reached out with a mitt and pulled me in, too. “We’ve been waiting,” he said. “I know,” Mom said, her voice muffled by his overalls. “I don’t think I remembered how far out it is.” Leo and Darlaine, having waited their turn, moved in, too. More hugs. More crying. Pinched cheeks on me, Darlaine’s doing, as she called me a beautiful boy. Torture. Sheer torture. “Jeff,” Grandpa said, holding me at an arm’s length. “What do you have to say for yourself?” “Nothing,” I said. “Well, you’ll need to do better than that.” “Mom says you’ve got corn here I can eat,” I said. “That we do.” “Where?” I asked. “Soon,” he said. “I’ll show you. What do you think of the place?” I cast a look around, for his benefit. All of them—Mom, Grandpa, Leo, Darlaine—had a look like something major would be hinging on my answer. “I’ve seen better,” I said. And then, deflation, right down the line. Grandpa gripped me by the neck, a gesture that looked loving enough but had a little pinch to it. I’d been mouthy. I knew I’d best not be mouthy again. “Well,” he said, “maybe that’s so. But someday you’ll lose a few things, and you’ll know better.” Because part of the exercise involves sharing both the memory and how the imagination was applied to it, here's closing the circle:

The memory: Hayloft was a word that led just about everybody to a farm, in one way or another. A word like that spawns more similarities, even in a large group, than a word like, say, forgettable would. I thought of the farm my grandfather grew up on, which I saw only once, when I was a little boy. I grabbed the name of his younger brother, Leo, and Leo's wife, Darlaine, because it was easier than making up new names. But Leo and Darlaine weren't the proprietors of the farm back then. (That would have been Forrest, another brother, and his wife, Margaret.) Everything else is imagination ... The imagination: Jeff's grandmother is conspicuous by her absence. My grandmother lived until 2017. Jeff's father isn't in the picture. Mine, both of mine, definitely were and are. I can't say I wasn't mouthy, or even that I don't remain mouthy, but I wasn't mouthy like that. I don't remember a hotel. Pretty sure we slept in campground barracks along with the rest of the out-of-town relatives that summer. Soon after that 1979 family reunion, we started losing people, which I'm sure is why it remains so firmly lodged in my mind. And so it goes. Really cool, unexpected, interesting things happen when I do The Word. It's why I love it so. 1/9/2023 0 Comments On Turning the PageAs I write this, it's late morning on Sunday, January 8, and I have spent an entire week living my new schedule. It looks something like this: 5:45 a.m.: Wake up, shower, tend to the dog, have some juice. 6:15 a.m.: Head downstairs to my office and begin writing. 7:30-7:45 a.m.: Head upstairs for breakfast. 8:30 a.m.: Start the rest of my workday. The rest of my workday is the part I've been waiting on. If this post is up and you're reading it, I've at last begun it.  My ready-for-a-new-job office, starting from the left bottom corner: reading nook, Fretless' kennel, writing space on the short side of the L-shaped desk, work station on the long side, stereo set. Out of the frame: book library and vinyl library. There's a drink fridge there under the left speaker. A comfortable office is an efficient office. I started working in a way that supports me when I was 18 years old, which means I've been at it for a long, long time. Most of that work has tied into a life of letters: I was a newspaper reporter before I was an editor, then I was a newspaper editor and a novelist, then I was a novelist and a freelance editor/graphic designer, then I was a novelist, freelance editor/graphic designer and pipeline inspection specialist (the latter being the wild card in my working life), then I was a digital journalist, a novelist, a freelance editor/graphic designer and a pipeline inspection specialist, then I dropped that last bit through no choice of my own.

As of today, I am an analyst/content specialist with a data research group that advises financial services on how to evolve digitally. And a novelist. And a freelance editor/graphic designer (although I'll be much choosier about my projects now). This new job, which I'm entirely stoked to begin, came about in a way that's reminiscent of how I've always found the most sustaining work I've done: a connection, an unforeseen opportunity, a perhaps surprising love of the work, and away we go. I've gotten to know folks at my new job over a series of years, working with them on a freelance basis first and now as a full-timer. Job changes, by their nature, can be stressful and uncertain. The way this came together mitigates some of that. I feel fortunate. And I'm just entirely grateful to have the opportunity, at this juncture of my life, to plant myself in something new and learn new skills while also applying the old ones in new ways. In the broad view, what I've always done is tell stories (pipelining, perhaps, notwithstanding, although have you met Max Wendt?). Here I go again. 11/8/2022 0 Comments Books for Our* KidsIt's Tuesday, November 8, the first snow day of the season in Billings. Ordinarily, I'd have stayed in, but today I went out, and I'm glad I did. I delivered 40 fresh new copies of my debut novel, 600 Hours of Edward, to Skyview High School in Billings. That was the last of four deliveries I've made to Billings schools, for a total of 150 books. And the beauty of this is that I am merely the messenger, the delivery driver. These books—to replenish previous (and tattered) copies of the novel that have been in the schools for around a decade—landed where they did because of a community that answered the call. I asked for donations, enough to purchase those 150 books at a steep discount from the publisher, and my community funded the campaign inside of 12 hours. And when I say community, I mean Billings—so many people in Billings—but I also mean the larger community I'm privileged to call my own. Teachers in Virginia kicked in donations. A coworker in Ohio ponied up. Friends in Texas. People I didn't know until some cash landed. They did this because I asked for help in putting books in kids' hands. In this strange time in America, when we hear so much about taking books away from kids, these generous donors put books in front of them. It's a beautiful, radical act. As I so often do when the subject turns to the ties that bind us, I give thanks to teachers for doing what they do even as a significant slice of the population wants to fight them, deny them what they do well, castigate and smear them. This is shameful, yes, but it's also not new, and we can either let these angry, outsized voices have the floor, or we can meet them with a different set of values. English teachers where I live were instrumental in getting 600 Hours on the approved curriculum reading list for the high school level here in Billings. They saw a contemporary story of a neurodivergent character, one set in the town where their kids live, and they did the heavy lifting to ensure that they could teach that book in their classrooms. As I said in the Billings Gazette article about the first book delivery—thank you, Gazette—those teachers' dedication puts a responsibility on me that I'm only too happy to carry. “They’re the ones who pushed for this book because they know how to reach these kids. And if they’re the ones who are making sure of that, I’ll be the one making sure they have the books.” Damn right. A word about the asterisk up above.

Yeah, they're our kids. I sometimes get a lot of pushback on this—"they're not my kids"—and I really wish someone taking the opposite view would spend just a little bit of time thinking expansively about the idea and the implications of abandoning it. My trip through public education was, in many ways, a disaster. It was also one of the most important factors shaping who I became and how I see the world. Certainly, public education is not perfect, and certainly, reasonable people can disagree on how to shape it, fix it, whatever. But we cannot, must not lose our responsibilities to ourselves and each other and the generations coming up behind us. Public education is a compact, an agreement that we will provide our kids with a basic education, as a community, knowing full well that our investments in those kids now are really an investment in our own future as a society. If we lose that, I'm afraid we lose everything else. So, today, I finished delivering some books. Backed by my community. Hopeful that the fight can be won. Determined to keep fighting, either way. 11/2/2022 0 Comments Launching ALL OF YOU

Now that the video is up at YouTube, I'd be grateful if you checked out this interview I did with my wife, Elisa Lorello, to mark the release of her new novel, All of You. I've been hoping for many, many years that I'd have a chance to get to know her better, so lucky me!

We get into a lot of stuff in a wide-ranging conversation (we really don't have any other kind). I'm just so proud of her and of this book, which is getting some rave reviews.

Want a signed copy? You can get it at our favorite bookstore, This House of Books in Billings, Montana. Just note in the comment box that you want it signed, and Elisa will oblige you. 10/12/2022 0 Comments The Past's PresenceEven though it's been a lively few weeks, Elisa and I have been feeling the pull of something peaceful. We scuttled our anniversary plans at the beginning of the month because Spatz the Cat was ailing, then a calendar filled with wonderful things—the High Plains Book Awards for me, a new novel launch for her—conspired against just-the-two-of-us time. Today, we grabbed a little of that, heading off on a day trip to one of our favorite places anywhere, Chief Plenty Coups State Park. There, less than an hour's drive from Billings, is a place both sacred and accessible to all, a preservation of the great chief's words and artifacts and vision. Every time we go, we take a lunch, then we visit the museum, then we take the long, looping walk around his home and his orchard, basking in the quiet and the peacefulness. A visit truly is a salve. On the drive back home to Billings, just outside the town of Pryor, I stopped for one more picture. You can't see much; the gate at the property was closed and locked, and my little iPhone camera couldn't do much with the scene.

Out there, though, is a house that once belonged to a rancher named Herman Hamilton, who is long dead and even longer not the owner of the spread. And somewhere on that patch of land where the house sits once sat a tiny little trailer home, way back in the early 1960s. It was there that my mother and father lived for a short while as Dad helped Herman tend to his ranch. The time that they lived there far predates me. They've been divorced for nearly 50 years—almost the entirety of my life—and probably haven't been in each other's presence more than a dozen times in all those years. When I'm with them in the same room, it's less a case of the gang is back together and more a case of my looking at them and wondering, "How the hell did this pairing ever happen?" (Answer: Youth and beauty and mutual desire. Move on, Craig.) Anyway, this isn't about that, not so very much. It's not even about this place that sits mere miles from somewhere Elisa and I regularly go. No, this is about the adage that gets fixed to Montana sometimes when it's described as one small town with really long streets. Herman Hamilton, you see, not only was my dad's long-ago employer but also was my best friend Bob's great uncle. Bob, whom I've known only since 2013 or so. Bob, who became friends with my dad because they both owned condominiums in the same development and were chatting one day and Dad mentions Herman Hamilton and Bob says, "Holy crap ..." The world really does shrink sometimes. (Herman was also a bank robber of some repute in the 1930s, but I suppose that's another story for another time.) 10/9/2022 0 Comments A Boy and His Town

And It Will Be a Beautiful Life, the novel that came out last year, won the 2022 High Plains Book Award for fiction last night. It's an honor that has left me gobsmacked and very, very proud, but this is only tangentially about that.

Here's the tangent: As part of the High Plains Book Awards festivities, finalists in the 12 categories were offered two nights at a Billings hotel. When that offer was extended a few months ago, Elisa and I looked at it and said "hey, much-needed staycation." By the time the dates rolled around, our cat had reached a point where she needed more hour-to-hour attention (she's fine, really, much better than we thought she'd be a couple of weeks ago), so Elisa and I spent time together during the days, then split at night. She came home, and I took the hotel room. "Staycation" became "mecation." It happens.

The hotel was close to a neighborhood in Billings where I once lived, in a different stage of my lifetime. Both mornings, I got up and took a long walk through North Elevation, a downtown-adjacent enclave of historic homes and wide streets and mature trees. It was less nostalgia—although there's nothing wrong with that—and more pure peace and beauty. Billings' signature park is there. A damn fine coffeeshop is, too. I had every reason to go and no reason not to. At the end of the first day's walk, I posted a Barenaked Ladies video on Facebook, along with this: "How it feels whenever I come to the North Elevation neighborhood ..."

I'm going to say now that I didn't quite capture the sentiment. "This is where we used to live" applies in a limited way, but the factors that make it past tense are more nuanced. The person with whom I lived there lives there still, from all appearances much more happily, and when you care about someone—as I do, still—you want only happiness for them. There's not a thing in those many blocks that is a heartbreak now, not even the memories of the pets I've loved who have crossed over. It's all good. Better than that, it's all beautiful.

Plus, I still live here. Not there, but here. The distance between the two is only a few miles and a good chunk of a lifetime.

When I heard the name of my book called out Saturday night, this is exactly what I thought of first: I'm home.

Not on a stage. Not standing next to two writers I consider wonderful friends. Billings, where I live. I said as much in my acceptance speech (if you can call it that; I was entirely unprepared, having not allowed myself to think my book might win): After nearly two years away in Maine, I came home to Billings in April 2020. I didn't know for how long. I still don't, as far as that goes. But this is where I used to live, and it's where I now live, and it's as home to me—all-the-way-in-my-bones home—as any place has ever been or is ever likely to be. That's what I thought of on those walks through an old neighborhood. That's what I thought of on that stage. That's what I'm thinking of now. And you know how it is when you're home: You know where you are. When we headed out for Maine in 2018, I described the leaving this way in an interview with Ed Kemmick and the late, lamented Last Best News: "There’s going to be that moment when I have to come to grips with the fact that I’m leaving the most important home that I’ve ever had and going somewhere else." So it did. But the leaving didn't take. I came back.  With the High Plains Book Award for best first book on October 8, 2010. With the High Plains Book Award for best first book on October 8, 2010.

The other thing I couldn't help thinking about Saturday night was a similar time, 12 years earlier to the day, when I was a much younger, much more ignorant man. In 2010, just months after my first novel was released, it won a High Plains Book Award. I might have been forgiven at that moment for thinking it would be forever thus: release a book, collect a prize. I might also have been gently prodded to see the bigger picture around me, because I was spectacularly screwing up some pretty basic parts of my life with neglect back in those days. I might have listened, adjusted, flown right.

Then again, I might not have done any of that. Being headstrong is its own affliction, cured by only one thing, if you're lucky enough to survive the medicine. My prescriptions were coming, about the writing life and about life, delivered in amazing highs and crushing lows, all the pain and pleasure I could ever want. Need another song? Try this one:

The joy is not the same without the pain.

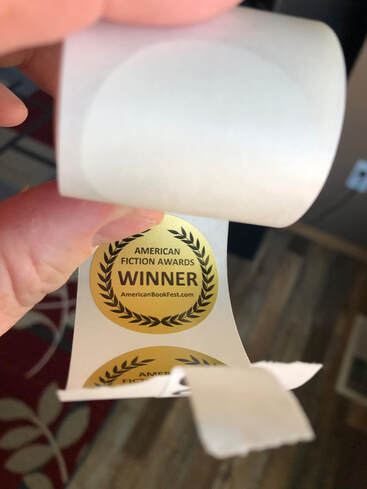

My mistakes are here in Billings. My regrets. My glories. My aspirations. The erstwhile friendships I hope I can repair. Still others I wouldn't even attempt to, mirages that they are. What's behind me and what's ahead of me, all of it ready to be examined and experienced. Most of all, the one I love, who has her own definitions of home, who is striving to be of it and in it. Together, we will honor those answers and those places, be they physical or emotional or both. So, before I go off on a burst of happiness, I should do this: In the interest of consistency and intellectual rigor, I must adhere to my basic sense that happiness, as an emotional state of being, is highly overrated. It's too reliant on current circumstance to be trustworthy, and the factors that spur it—good news, fortuitous coincidences, pure serendipity, and the like—are too transient to be relied upon. My aim in saying this isn't to knock happiness—if you have it, brother or sister, be thankful for it and keep it as long as you're able—so much as it is to cast a vote for its more durable cousin, fulfillment. If you're fulfilled in where you are, whom you're with, what you're doing, where you're headed, you have something to hold tight to when the transience of happiness is with you and when it's against you. That's my theory, anyway. That said, I'm pretty (burbly-happy curse word) happy these days. Let me count the reasons ... 1. One night in Big SkyI'm just back from Big Sky, about three hours from where I live. The board of the Big Sky Community Library chose And It Will Be a Beautiful Life as the community read (One Book Big Sky) for the fall. Tuesday night was sort of the capstone of the event. I drove out, had a wonderful chat with folks who read the book, spent the night, and came home. It was a soul restorer in all the best ways. When writers and writers gather, it can be a lovely thing (see below), but it can also be a release of the pent-up frustration that only writers know and thus are in position to help each other through. When readers and writers gather, it's straight-up love. How lucky was I to spend an evening with a bunch of people who read my book, read it closely, had such interesting things to say about it, and wanted to come talk with me? The luckiest. No doubt about it. I rode those good feelings all the way home. The drive from Big Sky to Bozeman is one of the most visually arresting things you can see anywhere in these United States, so there's that, and believe me, I drank it in (figuratively). I made stops at libraries in Bozeman, Livingston, Big Timber, and Columbus, planting seeds for more days and nights like the one I'd just enjoyed. Here's hoping. 2. The blessings of good friends With AMERICAN ZION author Betsy Gaines Quammen. With AMERICAN ZION author Betsy Gaines Quammen. I think I'm only just now getting my considerable arms around how emotionally bereft the pandemic has left me (and so many other people, judging from what I'm reading and what I'm hearing). Honestly, I thought being chased inside and away from gatherings was a small blessing amid a horrible event, but it wasn't that at all. Now that I can see and meet the people I want to see and meet—while still being careful, of course—I'm realizing how much I craved it. Just in these past few weeks, I've gotten to hang in Butte, Missoula (thank you, Gwen Florio and Malcolm Brooks), Livingston (thank you, Amy Zanoni and Maggie Anderson), Bozeman (thank you, Betsy Gaines Quammen and Kryssa Marie Bowman), and Big Sky. I've had the fellowship of brilliant writers and thinkers, genuinely good people, and people who lovingly tend to the cultural life writ large. Man. I've needed that so much. So much. Happy? Yeah, I'm happy. But grateful most of all. 3. The work is going well Winning an American Fiction Award was a lovely bit of news to receive. Winning an American Fiction Award was a lovely bit of news to receive. OK, look, here's where I keep it honest: If my publisher had said, sorry, kid, but your manuscript stinks and I'd received a lot of hate mail and my dog was snubbing me, would I be Mr. Happy? I would not. This, of course, underscores my point about fulfillment vs. happiness. I work to a standard I set so I can know I've done my best regardless of what a gatekeeper says (or, at least, so I'll have the gumption to try again if I find the door closed). I try to approach the world with an open heart because I believe that's how we get past at least some of our divisions. I engage with my dog so he knows I'm his, and he's mine. That's fulfillment. The happiness of it comes and goes. But I can't deny that I'm really, really enjoying every side of the work right now: The creation of it, when it's just me and an idea and the challenge of getting from here to there. The production of it, where I interact with the publisher I wanted to be with and who wants my work on his list. The carrying it to readers and interacting with them, which can be such an incredible validation of the work put in. The awards, both realized and potential (talk about transience). I'm as energized for all of it, the whole arc, as I've ever been. In Missoula, while waiting to eat lunch, I happened upon a meeting with a well-regarded poet and fiction writer and a genuinely good human. I don't know him well, but I like him, and even so, in the worst of my do-I-want-this-anymore crisis a few years ago, I deleted him (and a whole lot of other writers) from my social contacts, in a clumsy, flailing attempt at ridding myself of reminders of an endeavor I wasn't sure I wanted anymore. So there I was in Missoula, nonexistent hat in hand, apologizing for something I'm sure he didn't even notice, telling him I was in a dark place. He was kind and compassionate, as I expected he would be. I still appreciate the grace. I hope, the next time I'm on the other side of that conversation, I extend it to someone who needs it. I'd like to think I've learned something. Certainly, I appreciate that the want-to came back to me, and I'm going to nurture it as much as I can. But what happens when rejection arrives (as it surely will), or awards don't (ditto)? I don't know. I'll try to remember now and then and remind myself that I can be in both places. Just not at the same time. 3b. That was a lot. Here's an anecdote. So I'm driving home from Big Sky and I'm talking on the phone—hands-free—with Elisa and I'm saying much of what I said above, only differently, and I'm telling her how energized I am, and I'm hearing how energized she is, and we come around to You, Me & Mr. Blue Sky. It's the novel—a romantic comedy that goes deeper, as Elisa's work does—she and I wrote together in 2018 and 2019. We released it ourselves ... and pretty much let it flop around out there. Our crises of confidence coincided. Those were hard, broken days. We had no energy for much of anything, and certainly not for getting out and trying to introduce a book to the world. We were too adrift in our personal lives to have the fire for the professional. Frankly, there were times I wasn't sure we'd make it. But we did, and we have, and we're going to. Elisa is back, too, and she said, you know what, we should put a new jacket on that old novel we never really got behind. Freshen it up. It's a story of brightness and hope, and it has this dreary cover that doesn't fit it. Let's give it some love. OK, she didn't say that exactly, but that was the gist. And here it is, dressed to meet the readers we hoped it would meet. 4. Health Elisa didn't join me in Big Sky because our cat, Spatz, has been ailing. The most recent health issue was one that had a small sliver of hope for resolution and a rather wide, grim likelihood in terms of what we'd have to do. I had an appointment I had to keep, and Elisa decided to stay behind and tend to our girl. And our girl, not for the first time, has proved resilient. Her issue has resolved itself—or, at the very least, has recessed into a place where she's her old self again for however long that lasts. She was a surprise when she came into our lives, and we've resolved to enjoy her for as long as we have her. That horizon, delightfully, has widened. We're thrilled. As Elisa is given to saying, she's our Rushmore, Max. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

April 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed