|

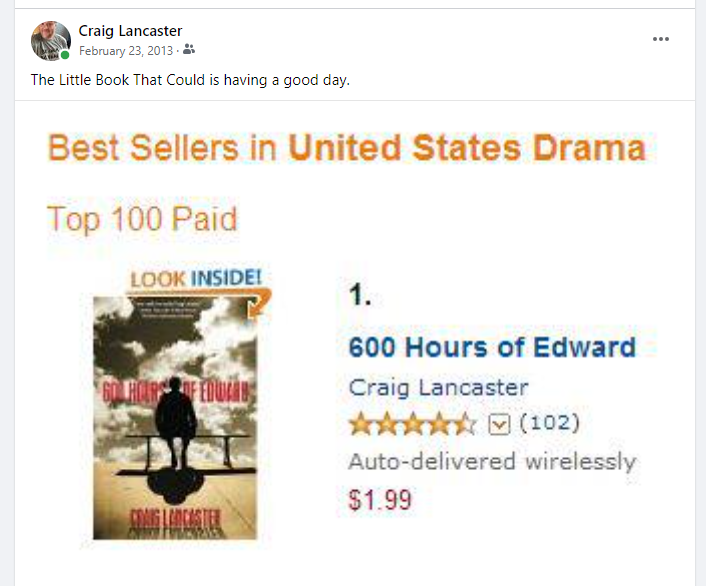

2/23/2024 0 Comments An Artifact of a Bygone EraThank goodness for Facebook memories—I guess—as I otherwise would not have seen that I posted this picture and this comment on my timeline 11 years ago: Eleven years seems like a long time ago, perhaps because it was a long time ago. And 11 years ago, I would have been loath to discuss the following topic, which I'm only too happy to discuss today: I am not, for the purposes of self-identity or self-esteem, a bestselling author or an international bestseller or an author whose works have been widely translated or a two-time High Plains Book Award winner. I am, for the purposes of advertising and marketing, all of those things. The differences between am not and am are profound, and learning to understand and appreciate those differences took me a long time and no doubt occasionally made me fairly insufferable. Live and learn. I think I can tell you exactly how my first novel, in 2013, went straight up to No. 1, if I may borrow from Bad Company. Of course, I'm biased in the analysis, so I'll tell you that writing a good book had something to do with it. I'm a realist, too, so I'll also say it had far more to do with a rising tide of readers eager to acquire e-books, a publisher with unparalleled access to those readers, and a price that encouraged those e-reader-wielding book lovers to take a chance on my novel without an onerous investment. Consequently, that book—and I—had a very, very good day (and week and month, and, really, a few good years). I'm nothing but grateful. And, sure, from a marketing perspective, I appreciate the bestseller label. It has had a far longer life than the actual bestselling ever did. We—the royal we of the publishing universe—hold fast to a bestseller status because we think it helps sell books. We festoon award stickers on hardcovers and paperbacks because we think it helps sell books. We seek out testimonials from other authors because we think it helps sell books. (And, on the flip side, we try to say yes to authors asking us to supply testimonials for their books because we really, really hope it helps sell books!) And at least to some extent, I'm certain all of that is helpful. But the degree of help is ephemeral and unmeasurable, and that's why the best an author can ultimately do is to (a) write the best book possible at the time of the undertaking and (b) work as hard as possible on its behalf once it has emerged into the world. Those are controllable factors. The rest...are not. Harder to accept, I think, is the truth that my friend Allen Morris Jones, one of my favorite authors, recently laid bare in his excellent newsletter, Storytelling for Human Beings: "There is very little rhyme to literary fame, almost no discernible reason. The breadth of your talent and the depth of your persistence are only a couple chunks of okra in that roiling, haphazard whatchagot stew of literary recognition. A few lucky souls end up making a reputation and a living. The rest of us tread water, watching our ship churn away over the horizon." That's sobering, yeah? Still, sobriety is vastly preferable to drunkenness on one's own marketing materials. I had a blast that day 11 years ago, I sold hundreds and hundreds of books, I made a fair amount of money (all of it now gone), and I didn't have to do anything stupid in the bargain. I'll continue to use the bestseller label, even if the fuller context is "author of a handful of bestselling books and a larger handful that you probably haven't read, not that he's complaining."

Luckily, the limited room on a book cover rewards brevity in these matters.

0 Comments

1/7/2024 3 Comments Sunday Morning Craft Talk*

*—if you'll indulge me.

Let's talk about sentimentality. The hook for this is simple enough; just yesterday, I posted something old/new at The Short Story Project: a 2011 story of mine called Comfort and Joy, which appears in my collection The Art of Departure. In the blurb that accompanies the post, I described the story as "unabashedly sentimental," which it is, then I proceeded to be bothered by that description for the next few hours, until I sat down to write this.

Why was I bothered? Perhaps because sentimentality is not highly regarded as a quality of serious fiction. While I'm fairly solid in my commitment to not caring terribly much what someone thinks of me personally—within limits, of course, my being human and all—I do get a bit crinkled when my work isn't taken seriously. See again: being human and all. Let me be clear here: I'm not holding out Comfort and Joy as some superior work of art. It's not. I haven't read it in years, but I know where it fell in the course of my fiction-writing career (early), and I'm certain that if I looked at it again, I would see much I wanted to do differently were I given another shot at it. But for better and worse—tilted heavily toward better—there are precious few do-overs in publishing. Mostly, you do it and live with it. I can live with Comfort and Joy. Its primary strength is this, more than a decade after it was written: It is precisely what I wanted it to be. I am taken with Capra-esque cinema, and I set out to write a Christmas story that captured a similar feel: an isolated old man with a compelling but obscure backstory, a little boy burdened by loss, a mother at loose ends, and the unlikelihood of their forging connections with each other. Happy ending? God, yes. Essential. Like George Bailey being rescued by the people whose lives he made better. Like Clarence getting his wings. Comfort and Joy hit every note I wished to play. Can you occasionally hear my fingers on the strings? Quite probably. But that's a limitation of the craftsman, not a failure of the story. One of my all-time favorite quotes is this one from Roger Ebert: "It's not what a movie is about, it's how it is about it." So it is with any artistic endeavor, I believe. Did you, the artist, do what you set out to do with the work? Yes? Congratulations! You've found success. What other people think you ought to have done is beside the point. Let them write their own stories if they feel so strongly about it.

My intent here is not to launch a spirited defense of my own work but to pose an essential question: If art is about the human condition—its variables, its beauty, its ugliness, and all the imaginable in-betweens—how can sentimentality be relegated to the outside of that? I'm not talking about the glorification of treacle or granting myself free rein to load up stories with so much sugar that readers' teeth fall out. I'm talking about acknowledging a human yearning for sentiment, a human response to what is stirred up in its wake, the emotional outlet it supplies. To my mind, it's rather like humor, another quality often underplayed and undervalued in so-called serious literature. Zaniness may not carry the heft and complexity of irony, but it damn sure offers a compelling reflection of humanity as I know it and aspects of human beings as I know them.

Finally, let's talk about happy endings.

There's little upside to being scholarly about my own work—let me acknowledge that before I say this next bit—but if my stories demonstrate anything, it's that the narrative and the pages eventually end but the story never really does. Think of Edward Stanton looking across the street or Mitch Quillen driving home to his kids, or, more recently, Max Wendt waiting to find out where the flow will take him next. There's so much story beyond the page, and my particular way of writing often compels me to put the responsibility in readers' hands when my words are expended: It goes somewhere from here. Where do you imagine that is? I love doing the same with the stories I'm told. George, the richest man in town, isn't going to jail or being run out of town on a rail. Is Potter? Will Nick someday move along and open a more rollicking joint for men who want to get drunk fast? Do George's kids eventually get out of Bedford Falls, the way he wished to, and will he encourage them in the way his own sainted father encouraged him? It's up to me. What a great privilege.

So, in my unabashedly sentimental short story, the ending comes as the old man stares out of a broken window and beholds unfettered joy. But the lives inhabiting the story, presumably, go on, into other days and moments, into other happinesses and heartbreaks, into gains and losses and despair and redemption. Experience enough of those things and you just might become sentimental about them.

5/19/2023 2 Comments Hey, Craig, I Have a Question ...Welcome to the first installment of what I hope can become an occasional series here: You pose a question, and I answer it. Today's question came unprompted from a Facebook friend, and the answer illuminates an interesting little side story to the Edward series of books. Let's dig in: Q: I started reading 600 Hours of Edward yesterday, and in one edition I have he mentions the Billings Gazette, but in another it's the Billings Herald-Gleaner. Since this is a rare occasion when I can ask an author a question I have about a book when I have it, why is that? I don't know that I've ever addressed this in a wide-open public forum before. To grasp what happened here, we must go back to the writing of 600 Hours of Edward. That's a long time ago (late 2008) and far, far away. (OK, not really. I wrote that book about five miles from where I sit right now.) In late 2008, when I was writing the first draft of 600 Hours, I was working nights at the Billings Gazette as a copy editor. I saw no problem with using the actual name of the paper in the manuscript. The paper was a small part of the story, and the invocation of the paper's name was benign. Nobody got impugned. Also, at that point, I had no way of knowing that this one story I was sort of writing on a lark would ever be published. The idea that it might someday grow into what it became, spawning two subsequent novels, would have been preposterous to allow into my head. So ... let's fast-forward to 2012 ... 600 Hours has been out for a few years, and quite unexpectedly, it has become a little underground success story. It hasn't sold many copies, but it has received a couple of nice awards and some good press. The original publisher, a small press here in Montana, has decided to sell the publication rights to a much larger publisher with an international footprint. This larger concern acquires those rights with the idea that it will release a brand-new version of the book in August 2012, followed by the sequel, Edward Adrift, in 2013.

Edward Adrift, as I don't have to tell anyone who's read it, features the Billings newspaper as a much bigger plot player. And the references are far less complimentary. My problem: At this point, I still work at the Billings newspaper. Not good. Not comfortable. So I reach out to my new publisher with a suggestion: How about we change the name of the newspaper in the original story to something entirely fictitious (that right there is what we call plausible deniability!) and carry that new name through the sequel? Thus was born the Billings Herald-Gleaner (because if you're going to put a fake name on your newspaper, make it a funny one). I did realize we would leave some readers confused, but frankly, it's a pretty small number. I think the original version of 600 Hours of Edward sold fewer than 1,000 copies, and the 2012 re-release has sold upward of 200,000 across all of the languages in which it appears. For the vast preponderance of readers of the Edward books, the newspaper is and has always been the Billings Herald-Gleaner, not the Billings Gazette. Meanwhile, changing the newspaper's name meant I could continue to go to work without fear of having insulted my employer in a way that would have harmed either of us. A couple of final takeaways: My career at that newspaper ended just a few months after Edward Adrift was released, so I don't think changing the name of the paper in the book had any real effect, other than making me feel better about things. But there's a larger lesson here, one I've applied in the writing of subsequent books: It's fiction, so why not be fictitious? Business names, particularly, tend to be transient anyway. In an odd way, a piece of fiction can remain a lot more timely with invented references than it can with references to real-life things that might not survive a shift in fortunes or consumer habits. 2/24/2023 4 Comments The Best That You Can Do*

* Not just the words to a Christopher Cross/Burt Bacharach/Carole Bayer Sager/Peter Allen song.

Sorry. I had to.

Wait, strike that. I'm not sorry.  Tiffany Yates Martin, a book editor who also writes under the name Phoebe Fox. (FoxPrint Editorial) Tiffany Yates Martin, a book editor who also writes under the name Phoebe Fox. (FoxPrint Editorial)

The possible mechanical aspects of the writing life—what to write, when to write, what time to write, how much to write, etc.—are so many and so varied that I've discovered I can disagree with just about anything, given the opportunity to formulate a contrary opinion or just to wake up in a mood.

But once in a while, something crosses my desk or screen that inspires nothing but rabid agreement in me. My friend Tiffany Yates Martin—in fairness, my wife's editor on several projects, but I joined the two of them for a memorable and hilarious lunch in Austin, so I'm claiming her—wrote just such a piece earlier this week. You can read it for yourself, but here are just a couple of the stellar observations: I think there’s danger in talking about our writing in a diminishing way. Most obviously it sends us the message that our creative work isn’t that important or worthwhile. It’s just a lark, a silly little whim we pursue, but we’re not kidding ourselves that we can stand beside the actual greats of literature. And ... That means having a clear-eyed view of your work and where there may be room for improvement and growth, while also allowing yourself to be proud of its merits and strengths. Without that how can we hope to improve as artists, any more than a child who is given nothing but criticism and disapproval can develop a healthy self-image and flourish? We have to create a safe space for ourselves as artists where we have permission to fail, permission to grow. Seriously, if you are one of those "oh, I just write [whatever]" or "I just dabble" writers, go read Tiffany's piece and see if, perhaps, there's a way to recast your thinking into something that's realistic and celebratory. You create things. You conjure stories and experiences. You're awesome. Never forget it.

Years ago, after my second novel, The Summer Son, came out, it landed reviews in two regional publications that I fervently hoped would shower it with praise. I was riding high, at least from a critical standpoint, having seen my debut, 600 Hours of Edward, receive wide praise and some nice awards. I thought I'd written an even better book with The Summer Son, so I readied myself for an onslaught of plaudits.

The novel went 0-for-2 in redeeming those hopes. The review in New West was generally complimentary but cast the book as falling short of its predecessor. The review in the Missoula Independent was more of a split-personality assessment—which, interestingly, is what the reviewer accused my book of having—with effusive praise for the character development and something bordering on ridicule for the plotting. I know what my reaction was, in both cases: something deeper than disappointment and a bit short of despondency. (I suppose I'm blessed/cursed by not really giving a damn what you think of me, but I get a little bruised when my work isn't seen favorably.) It was fascinating to see reactions from my friends and colleagues. A couple called me to make sure I was OK. One told me the Independent piece was an unqualified great review, a point of view I had a little trouble accessing. (Her point, I believe, is that character development is the gold standard of literary work, and I'd won the critic over with that part of my effort. OK, then.) The point of all this isn't to indulge in ancient grudges, although if I were so inclined, I'd point out that both New West and the Independent are dead and The Summer Son still puts money in my pocket every month, so chomp on that, fellas. But I am not so inclined. The fact is, the literary life of the West is poorer for those publications' absence, no matter how wrong they were on occasion. (OK, maybe just a little jab.) No, seriously, my point is this, and it's one I've made again and again: If you want something you can influence with regard to your work, better to forget how it'll be received, whether it will sell, if it'll make you rich, and put all of your attention on doing the absolute best work you're capable of undertaking at the time you undertake it. If you do that, if you're certain it's the best that you can do, you will owe no one anything. You will owe only yourself, and only this: growth, the gumption to try even harder the next time, a willingness to stretch yourself beyond what you think is possible. Some years after those reviews, I was talking with the guy who wrote the one for New West, a good friend of mine and a damn fine writer, and told him he'd certainly been right about certain things. I'd grown. I could see flaws I didn't see at the time I wrote it. I said something like "if I could do it over again, I would." And he set me straight: "Don't ever say that about your own work. Don't ever put it down." Absolutely right. You made that. Love it for what it is. Save "I should have done better" for next time, then do it. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed