|

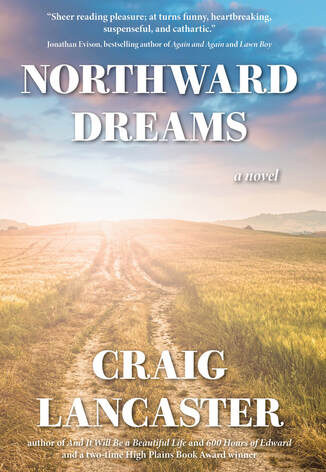

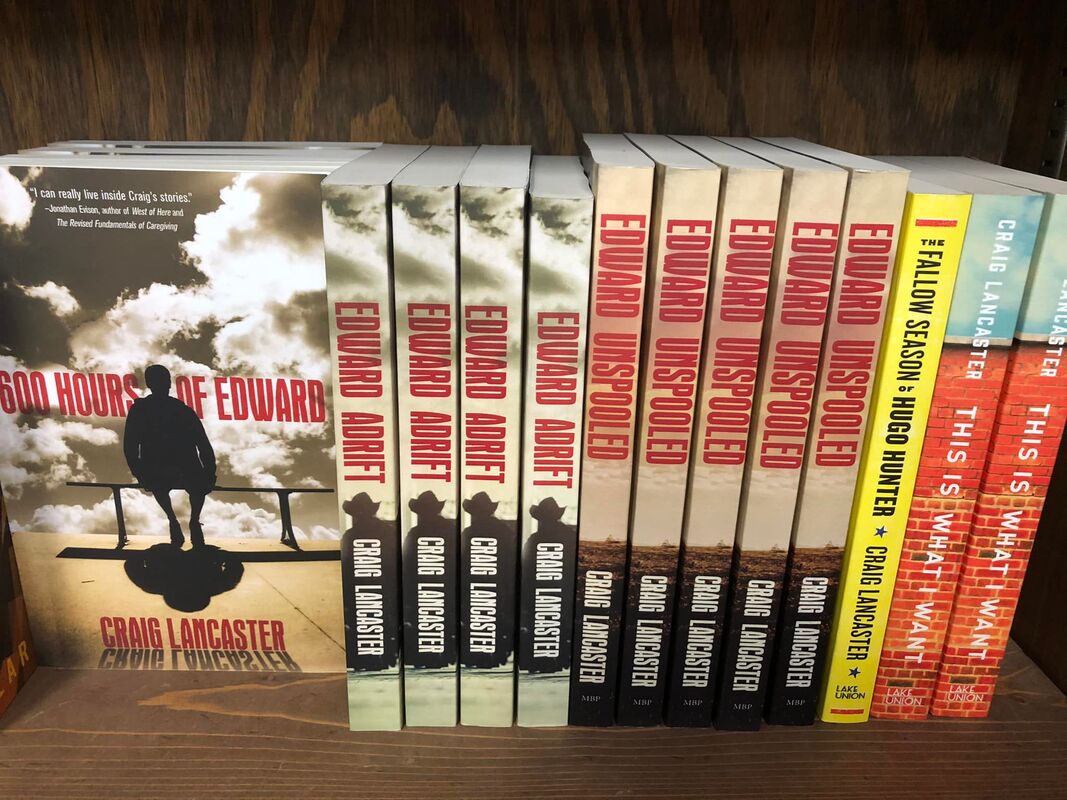

(Note: The original version of this post went up several months ago, in anticipation of the release of my new novel. That release never happened, at least not with the original publisher and not in the original form. But I feel too strongly about this piece to just let it go, so here it is, with some revisions to reflect the novel's current reality.)  I. On The Feeling My tenth novel, Northward Dreams, is just days away from its release date. I’m no more impervious to big, round numbers than anyone else is, and the imminent publication of a tenth novel—particularly when I once had serious, serious doubts that I’d ever write, much less publish, even one—is a good occasion for a bit of reflection. I’ve learned a lot about how to do this, enough that sometimes I’m even prepared to believe I’ve gotten good at it. I’ve learned a lot about humility, which forecloses any chance that I’ll linger long on “gee, I’ve gotten good at this.” (These latter-day lessons in being humbled have been particularly instructive. See the section titled On the Things That Aren't Love for more on that.) I’ve learned a lot about what’s fleeting and what’s durable. I’ve learned that it’s all about love. What that what the last bit looks like, for me, hinges on memory and imagination, the crucial elements of fiction, in my estimation, but also fairly punchless without love. It’s loving the work. Loving the characters who get conjured in the work. Loving each new project with the whole of your heart, even if—and especially if—you must love it enough to let it go. There has been a lot of this, more than I ever imagined there could be. When I get down to diagnosing why an idea didn’t take off the way I hoped it would, I almost always land on a memory to which I’ve insufficiently connected, which bogs down the imagination that is supposed to turn it into fiction, which subsequently demands the love that makes me say “this is not for me.” (If I were as good at that in my beyond-the-page life as I am in my writing life, I wouldn’t bruise so easily. But I digress.) Conversely, the idea that soars, that becomes something I see through to completion, is almost always built on the back of a memory, slathered with imagination, that becomes something else again. It’s almost magical, that feeling, even as it remains hard, word-rock-busting work to bring it forth. I love (that word again) that feeling. I chase it. Again and again and again. II. On Memory and Love A couple of years back, in an interview with Montana Quarterly (where I’ve been on the masthead since 2013), the great Larry Watson said something so profound that my greatest wish was that I’d said it first. Failing that, I cite this quote endlessly, with all due credit to Mr. Watson: I write from memory, not observation. Yet my memories are formed from observations, and then memory and imagination distort those observations into something useful for fiction and something that’s also truthful in its own way. That’s the ballgame, right there. Unsaid, but screamingly evident to anyone who has read Watson’s work, is the part where love comes in. That manifests in doing the work, in riding the work out, in achieving empathy with your characters, in knowing when to make the gradual turn from I’m writing this to engage my own need for the work to I’m writing this for someone to read someday, and thus I must be attentive to what it needs to be. Love is showing up faithfully. Love is holding at bay the world that will threaten your enthusiasm, your want-to, your ability to separate those things over which you have control and those that are mysterious variables. Love is having a standard for the work. Love is absolving yourself when, say, a pandemic swallows up your work like it never existed in the first place. It did. Your love made it manifest. Love is also forgiving yourself when you could have done better and somehow didn’t. Love is believing that you’ll do right by it the next time. Love is faith, and you’re gonna need a lot of it. Arthur Miller—I borrow only from the best—knew something about the staying power of the deeply imprinted memory. Perhaps nothing is as creatively propulsive as the blown chance, the missed boat, the shameful moment, the deep regret, the thing you ache to understand, the love you couldn’t hold. Here he is: Maybe all one can do is hope to end up with the right regrets. If you’ve had a bit of therapy—and only about eight percent of us have, which means ninety-two percent of us are in deficit—you’ve probably been told that regret is a feeling wasted on the unsustainable belief that you should have been perfect. Insofar as it applies to our lives and how we face up to them, I’m inclined to concede the point. But for the author who mines memory for stories, regret—particularly the right kind, which Miller doesn’t identify and thus is open to personal definition—is creative fuel. As I look back on ten novels, I see work and characters suffused with what I could give them through my grappling with memory and regret. Neurodivergent Edward Stanton (600 Hours of Edward, Edward Adrift, Edward Unspooled) and his fights with an illogical world. Mitch Quillen and his intractable father (The Summer Son). Hugo Hunter and his clay feet as a fighter and a father and a friend (The Fallow Season of Hugo Hunter). The Kelvig clan and their town and the pulling apart of what binds them (This Is What I Want). Sad-sack Carson McCullough and the demise of the newspaper business (Julep Street). Jo-Jo and Linus and the vagaries of attraction (You, Me & Mr. Blue Sky). Max Wendt and the status quo he doesn’t see crumbling (And It Will Be a Beautiful Life). And now, Northward Dreams, perhaps the most personal work of them all, one that required me to find the memory—and, always, the love—and enough imagination to make it something more than a transcript. So much more. So surprising in the end. So familiar that it could have kissed me. I’m in love. It keeps happening. III. On Imagination and Love How does this memory-fortified-with-imagination-backed-by-love thing work, in practical terms?I have an object lesson for that, drawn from Northward Dreams and its ingredients. The memory: If I’m prompted to give a short-hand accounting of who I am and how I got here, I say that I grew up in Texas and found my way to Montana as quickly as I could. The truth is a bit more nuanced. I wasn’t that quick. I got here when I was thirty-six years old, time enough for a dozen places in the interim that I tried, to varying degrees of success to make home. My first home, in fact, after I was born in Washington state and adopted by my parents, was in Mills, Wyoming, a little bedroom community north of Casper. For the first three years of my life, I lived in tiny clapboard house on an unpaved street, which sat across the street from one of the town’s water towers. After my mother left my father and moved us to Texas, I was largely absent from Mills save for occasional summer visits to see my dad. But the image of that water tower embedded in my psyche. Whenever I would see one like it, particularly in my suburban Texas town, I would feel the pangs of separation from my father. The imagination, in excerpt form: Ronnie goes down to the floor with his boy for a close-up view of the gas station in miniature. He watches as two round-headed figurines in a car, into which they fit like pegs, ride the elevator up to the top floor and the door opens and the car rolls out and careers down the ramp to the carpet beneath them. “Ain’t that something?” he says, and the boy squirms happily. “I got it for Christmas last year,” Nathan says. “I remember,” Ronnie says, a harmless lie, he thinks. “Hey, I saw that kid Richard, your friend, the other day. He says hello.” “He’s nice,” Nathan says. “Yeah, he’s a good kid.” Nathan bounces up and grabs his father’s hand. Ronnie clambers to his feet. “Come here,” Nathan says, tugging him. “OK.” Nathan pulls him to the window that looks out upon the suburban expanse. “See that?” “Yeah,” Ronnie says. “Buildings.” “No, that.” Nathan points, insistent. “What?” “The blue thing.” Ronnie stares down. “What blue thing?” “No, there.” The boy redirects his indicator, trying to get his father to follow the line. “The water tower?” “Yes.” “Yeah, I see it,” Ronnie says. “That’s where you live.” “It is?” “Yes. I live here. You live over there.” “No, son.” “Yes.” “No.” Ronnie makes a quarter-turn, facing the wall. He points at the blankness of it. “It looks the same as our water tower, but I live a thousand miles that way. North. Where you used to live.” He turns back to the window and points again. “That over there, that’s east. Understand?” “No.” “Well, come downstairs, Sport, and I’ll try to explain it, OK?” The love: It starts with what I feel, and have felt, for my father, a love that’s been constant but ever changing, ever shifting depending on the circumstances we find ourselves in. The unquestioning adoration I had for him when I was a little boy got replaced by an exasperated pity the more I learned about him and the more I witnessed. That, in turn, got supplanted by the responsibility I take for him in his dotage, the insistence I have of seeing him off this mortal coil and keeping fear, terror, and pain as far from him as I can. As his infirmities grow and he lashes out, I find myself with more and more days when I love him and simultaneously hope I can find a way to like him again. It’s not for wimps, this love thing. The water tower the boy points at insistently was, and is, in a Mid-Cities suburb between Fort Worth and Dallas, a town called Hurst. I used to climb into the tallest tree of my neighborhood in an adjoining town and find it on the flat horizon and try to convince myself that it was Mills, Wyoming, and that my father might be there at the base of it. I didn’t know north from east in those days. I couldn’t have envisioned the magnitude of a thousand miles. I just knew blue, cylindrical water towers and that one was in proximity of a man I missed. I tucked it all away. Years later, it came pouring out of me, a strong current of memory washed in imagination. That’s love. IV. On the Things That Aren’t Love

Soon after my third novel, Edward Adrift, came out in 2013, I was making enough money in royalties to grant serious consideration to trying to make a go of it as a full-time novelist. I had the big-time New York agent, a slew of foreign translations, a full calendar, and novels-in-progress lined up on the runway. My then-publisher had feted the onset of our relationship with “we want to be in the Craig Lancaster business.” That’s something—indeed, I suspect it’s something that most any author not in the one percent craves—but it’s not love. It’s validation, it’s success, it’s the fruits of one’s efforts, it’s unadulterated luck, but it’s not love. Love is what you give yourself when the royalties dry up, the big-time New York agent moves on from you, the foreign translations are harder to attract, the calendar is empty, and the ideas are taking on rust. When your publisher doesn’t want to be in the “you business” anymore. When the publisher you subsequently love makes promises that don't pan out and you pull a book just a day before it's supposed to come out, knowing you'll end up hating yourself and maybe him if you don't. And you don't want to hate anybody. Find love through that. It's not easy. But it's worth every effort you can give it. These are all things that can shoot your horse right out from under you. I’m not suggesting that you—or anyone—should just buck up and get through it, as if it’s not there, in your path like a boulder you can’t circumnavigate. Lean on your supports. Get your ass into therapy if you need it (ninety-two percent of us do!). Divert yourself with a hobby or a road trip or whatever. Take some time off, if that’s what’s calling to you. Don’t stop pushing, if pushing is what’s demanded. And while you’re doing all of that, remember the love. The love of a memory, an idea, an approach. The love of the work. The love of the characters and the settings and the structure of what you’re trying to create. The love of revising it and honing it until it’s just what you want. The love of taking the finished thing—the first or the tenth or the hundredth—and offering it up with a hopeful, open heart. I made this. I fell in love. Again.

0 Comments

10/9/2022 0 Comments A Boy and His Town

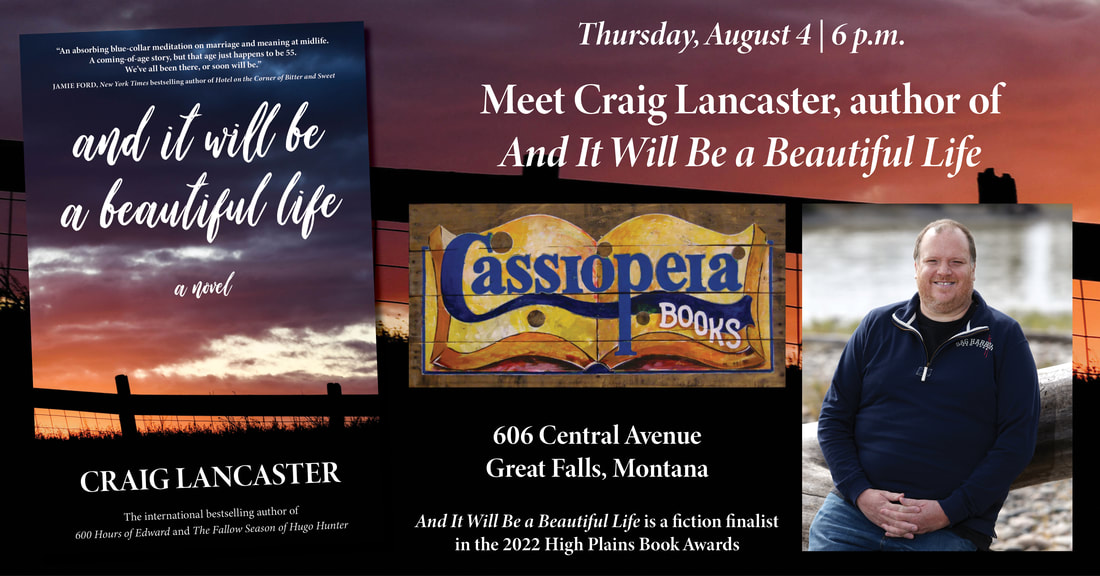

And It Will Be a Beautiful Life, the novel that came out last year, won the 2022 High Plains Book Award for fiction last night. It's an honor that has left me gobsmacked and very, very proud, but this is only tangentially about that.

Here's the tangent: As part of the High Plains Book Awards festivities, finalists in the 12 categories were offered two nights at a Billings hotel. When that offer was extended a few months ago, Elisa and I looked at it and said "hey, much-needed staycation." By the time the dates rolled around, our cat had reached a point where she needed more hour-to-hour attention (she's fine, really, much better than we thought she'd be a couple of weeks ago), so Elisa and I spent time together during the days, then split at night. She came home, and I took the hotel room. "Staycation" became "mecation." It happens.

The hotel was close to a neighborhood in Billings where I once lived, in a different stage of my lifetime. Both mornings, I got up and took a long walk through North Elevation, a downtown-adjacent enclave of historic homes and wide streets and mature trees. It was less nostalgia—although there's nothing wrong with that—and more pure peace and beauty. Billings' signature park is there. A damn fine coffeeshop is, too. I had every reason to go and no reason not to. At the end of the first day's walk, I posted a Barenaked Ladies video on Facebook, along with this: "How it feels whenever I come to the North Elevation neighborhood ..."

I'm going to say now that I didn't quite capture the sentiment. "This is where we used to live" applies in a limited way, but the factors that make it past tense are more nuanced. The person with whom I lived there lives there still, from all appearances much more happily, and when you care about someone—as I do, still—you want only happiness for them. There's not a thing in those many blocks that is a heartbreak now, not even the memories of the pets I've loved who have crossed over. It's all good. Better than that, it's all beautiful.

Plus, I still live here. Not there, but here. The distance between the two is only a few miles and a good chunk of a lifetime.

When I heard the name of my book called out Saturday night, this is exactly what I thought of first: I'm home.

Not on a stage. Not standing next to two writers I consider wonderful friends. Billings, where I live. I said as much in my acceptance speech (if you can call it that; I was entirely unprepared, having not allowed myself to think my book might win): After nearly two years away in Maine, I came home to Billings in April 2020. I didn't know for how long. I still don't, as far as that goes. But this is where I used to live, and it's where I now live, and it's as home to me—all-the-way-in-my-bones home—as any place has ever been or is ever likely to be. That's what I thought of on those walks through an old neighborhood. That's what I thought of on that stage. That's what I'm thinking of now. And you know how it is when you're home: You know where you are. When we headed out for Maine in 2018, I described the leaving this way in an interview with Ed Kemmick and the late, lamented Last Best News: "There’s going to be that moment when I have to come to grips with the fact that I’m leaving the most important home that I’ve ever had and going somewhere else." So it did. But the leaving didn't take. I came back.  With the High Plains Book Award for best first book on October 8, 2010. With the High Plains Book Award for best first book on October 8, 2010.

The other thing I couldn't help thinking about Saturday night was a similar time, 12 years earlier to the day, when I was a much younger, much more ignorant man. In 2010, just months after my first novel was released, it won a High Plains Book Award. I might have been forgiven at that moment for thinking it would be forever thus: release a book, collect a prize. I might also have been gently prodded to see the bigger picture around me, because I was spectacularly screwing up some pretty basic parts of my life with neglect back in those days. I might have listened, adjusted, flown right.

Then again, I might not have done any of that. Being headstrong is its own affliction, cured by only one thing, if you're lucky enough to survive the medicine. My prescriptions were coming, about the writing life and about life, delivered in amazing highs and crushing lows, all the pain and pleasure I could ever want. Need another song? Try this one:

The joy is not the same without the pain.

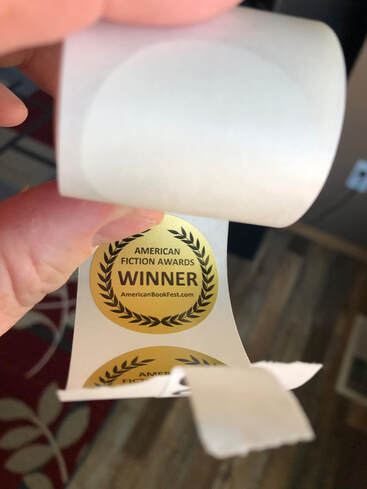

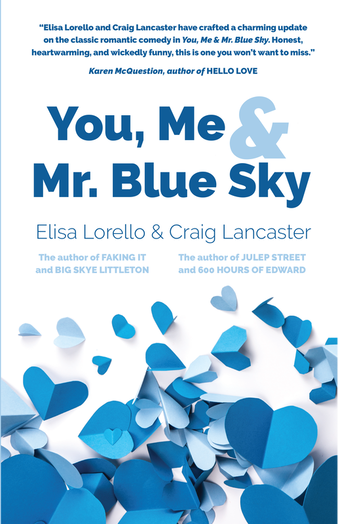

My mistakes are here in Billings. My regrets. My glories. My aspirations. The erstwhile friendships I hope I can repair. Still others I wouldn't even attempt to, mirages that they are. What's behind me and what's ahead of me, all of it ready to be examined and experienced. Most of all, the one I love, who has her own definitions of home, who is striving to be of it and in it. Together, we will honor those answers and those places, be they physical or emotional or both. So, before I go off on a burst of happiness, I should do this: In the interest of consistency and intellectual rigor, I must adhere to my basic sense that happiness, as an emotional state of being, is highly overrated. It's too reliant on current circumstance to be trustworthy, and the factors that spur it—good news, fortuitous coincidences, pure serendipity, and the like—are too transient to be relied upon. My aim in saying this isn't to knock happiness—if you have it, brother or sister, be thankful for it and keep it as long as you're able—so much as it is to cast a vote for its more durable cousin, fulfillment. If you're fulfilled in where you are, whom you're with, what you're doing, where you're headed, you have something to hold tight to when the transience of happiness is with you and when it's against you. That's my theory, anyway. That said, I'm pretty (burbly-happy curse word) happy these days. Let me count the reasons ... 1. One night in Big SkyI'm just back from Big Sky, about three hours from where I live. The board of the Big Sky Community Library chose And It Will Be a Beautiful Life as the community read (One Book Big Sky) for the fall. Tuesday night was sort of the capstone of the event. I drove out, had a wonderful chat with folks who read the book, spent the night, and came home. It was a soul restorer in all the best ways. When writers and writers gather, it can be a lovely thing (see below), but it can also be a release of the pent-up frustration that only writers know and thus are in position to help each other through. When readers and writers gather, it's straight-up love. How lucky was I to spend an evening with a bunch of people who read my book, read it closely, had such interesting things to say about it, and wanted to come talk with me? The luckiest. No doubt about it. I rode those good feelings all the way home. The drive from Big Sky to Bozeman is one of the most visually arresting things you can see anywhere in these United States, so there's that, and believe me, I drank it in (figuratively). I made stops at libraries in Bozeman, Livingston, Big Timber, and Columbus, planting seeds for more days and nights like the one I'd just enjoyed. Here's hoping. 2. The blessings of good friends With AMERICAN ZION author Betsy Gaines Quammen. With AMERICAN ZION author Betsy Gaines Quammen. I think I'm only just now getting my considerable arms around how emotionally bereft the pandemic has left me (and so many other people, judging from what I'm reading and what I'm hearing). Honestly, I thought being chased inside and away from gatherings was a small blessing amid a horrible event, but it wasn't that at all. Now that I can see and meet the people I want to see and meet—while still being careful, of course—I'm realizing how much I craved it. Just in these past few weeks, I've gotten to hang in Butte, Missoula (thank you, Gwen Florio and Malcolm Brooks), Livingston (thank you, Amy Zanoni and Maggie Anderson), Bozeman (thank you, Betsy Gaines Quammen and Kryssa Marie Bowman), and Big Sky. I've had the fellowship of brilliant writers and thinkers, genuinely good people, and people who lovingly tend to the cultural life writ large. Man. I've needed that so much. So much. Happy? Yeah, I'm happy. But grateful most of all. 3. The work is going well Winning an American Fiction Award was a lovely bit of news to receive. Winning an American Fiction Award was a lovely bit of news to receive. OK, look, here's where I keep it honest: If my publisher had said, sorry, kid, but your manuscript stinks and I'd received a lot of hate mail and my dog was snubbing me, would I be Mr. Happy? I would not. This, of course, underscores my point about fulfillment vs. happiness. I work to a standard I set so I can know I've done my best regardless of what a gatekeeper says (or, at least, so I'll have the gumption to try again if I find the door closed). I try to approach the world with an open heart because I believe that's how we get past at least some of our divisions. I engage with my dog so he knows I'm his, and he's mine. That's fulfillment. The happiness of it comes and goes. But I can't deny that I'm really, really enjoying every side of the work right now: The creation of it, when it's just me and an idea and the challenge of getting from here to there. The production of it, where I interact with the publisher I wanted to be with and who wants my work on his list. The carrying it to readers and interacting with them, which can be such an incredible validation of the work put in. The awards, both realized and potential (talk about transience). I'm as energized for all of it, the whole arc, as I've ever been. In Missoula, while waiting to eat lunch, I happened upon a meeting with a well-regarded poet and fiction writer and a genuinely good human. I don't know him well, but I like him, and even so, in the worst of my do-I-want-this-anymore crisis a few years ago, I deleted him (and a whole lot of other writers) from my social contacts, in a clumsy, flailing attempt at ridding myself of reminders of an endeavor I wasn't sure I wanted anymore. So there I was in Missoula, nonexistent hat in hand, apologizing for something I'm sure he didn't even notice, telling him I was in a dark place. He was kind and compassionate, as I expected he would be. I still appreciate the grace. I hope, the next time I'm on the other side of that conversation, I extend it to someone who needs it. I'd like to think I've learned something. Certainly, I appreciate that the want-to came back to me, and I'm going to nurture it as much as I can. But what happens when rejection arrives (as it surely will), or awards don't (ditto)? I don't know. I'll try to remember now and then and remind myself that I can be in both places. Just not at the same time. 3b. That was a lot. Here's an anecdote. So I'm driving home from Big Sky and I'm talking on the phone—hands-free—with Elisa and I'm saying much of what I said above, only differently, and I'm telling her how energized I am, and I'm hearing how energized she is, and we come around to You, Me & Mr. Blue Sky. It's the novel—a romantic comedy that goes deeper, as Elisa's work does—she and I wrote together in 2018 and 2019. We released it ourselves ... and pretty much let it flop around out there. Our crises of confidence coincided. Those were hard, broken days. We had no energy for much of anything, and certainly not for getting out and trying to introduce a book to the world. We were too adrift in our personal lives to have the fire for the professional. Frankly, there were times I wasn't sure we'd make it. But we did, and we have, and we're going to. Elisa is back, too, and she said, you know what, we should put a new jacket on that old novel we never really got behind. Freshen it up. It's a story of brightness and hope, and it has this dreary cover that doesn't fit it. Let's give it some love. OK, she didn't say that exactly, but that was the gist. And here it is, dressed to meet the readers we hoped it would meet. 4. Health Elisa didn't join me in Big Sky because our cat, Spatz, has been ailing. The most recent health issue was one that had a small sliver of hope for resolution and a rather wide, grim likelihood in terms of what we'd have to do. I had an appointment I had to keep, and Elisa decided to stay behind and tend to our girl. And our girl, not for the first time, has proved resilient. Her issue has resolved itself—or, at the very least, has recessed into a place where she's her old self again for however long that lasts. She was a surprise when she came into our lives, and we've resolved to enjoy her for as long as we have her. That horizon, delightfully, has widened. We're thrilled. As Elisa is given to saying, she's our Rushmore, Max. 8/14/2022 0 Comments Small. Appreciative.

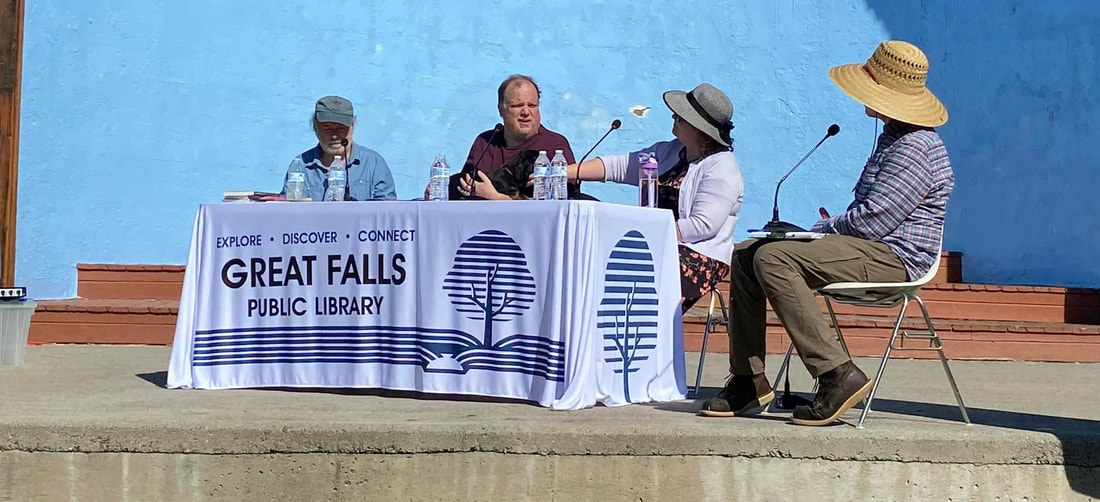

Life has some funny cycles. As I write this, I'm just a handful of hours home from a couple of days in Great Falls, that visit coming on the heels of another Great Falls trip the previous week. Before that, I think the last time I was in Great Falls other than just passing through was ... 2010? 2011? A long time ago. I hope this means I'll be going back sooner rather than later. I like that town.

I was there to take part in a panel discussion of Montana authors, sponsored by the Great Falls Public Library as part of the Big River Ruckus festival. It was a blistering-hot morning, and my planet-sized melon sizzled. As is often the case for literary events, we didn't have a big crowd (I believe the applicable adjectives are "small" and "appreciative"), but we had good times in abundance. I joined poet Dave Caserio (a Billings denizen, like me) and writer Kristen Inbody, and we had a rollicking good time talking about writing in the West, ideas, how place figures into our writing, and much more.

Whenever I do an event, I'm put in mind of a line from a Pernice Brothers song: It doesn't matter if the crowd is thin / we sing to six the way we sing to ten ...

It's a funny line, of course, but the sentiment is dead-on. I've seen everything there is to see at readings, book signings, and the like: small gatherings, no gatherings, full houses, whatever. Whatever you get, you deliver as best you can to whoever was kind enough to show up. It's a charming business in that way. Every hand that's there to shake—or the only hand that's there to shake—is another chance to make a connection. And connections are everything. One person showed up? Great! Take that person out for dinner or a drink. The whole town showed up? Fantastic! Now you've got a party.

Love is love, and we love the stage ...

Before heading home Sunday, I drove out northwest of Great Falls to see the dairy farm my father grew up on. It was only the third time I've been there, and the second was just a drive-by, but I remembered the route just fine. I drove down the long driveway to where the house is, but nobody came out, and I wasn't about to go knocking on doors, so I took a quick look, then slipped out of there quietly.

Here's a nice shot from atop the bench, about a mile and a half from the farmhouse. Sorry for the telephone pole bisecting Square Butte.

When I talk about writing and where it comes from, as I did during our discussion Saturday, I'm apt to talk about how we are born with stories. We're not blank slates. Going to a place that was formative for my father (in mostly devastating ways, unfortunately) is a good demonstration of what I mean. It allows me to put eyes on his life, to process it, and to make sense of my own. Because of the way his life was shaped by his early experiences, he had a story to transfer to me, one that I would start to carry when I came into the world, along with the one I would live out in my own days. The same is true, of course, with my mother, and her parents, and his parents, and their parents before them, and on and on. The stories are inside us, already coded. We draw them out, interpret them, weave them with imagination and memory (in the case of fiction), give them purpose. It's a beautiful thing. Even when the underlying material is made up of mostly terrible things.

"Before you climb the mountain, first the foothills must appear."

It was a long, hot, empty drive home for Fretless and me. He mostly slept. I mostly sang along with the random shuffle of iTunes, something I can get away with when I'm alone. (I certainly wouldn't subject any human to my singing voice.)

On the final stretch home, I received a particular delight when iTunes served up one of my favorite songs but also one that doesn't often swim to the top of the heap. I suppose most songs remind us of something, someone or some point in time. Certainly, this one does that for me. There's a tinge of melancholy, though, because it's a reminder of a friendship I miss. It's been many years since it went by the wayside, and I've come to embrace something I was told a long time ago when I was seeing a counselor while in the midst of divorce: Some friendships are like cab rides. They have a beginning and an end. Indeed, they do.

Anyway, it was nice to hear the song at that moment, with my head where it was (reeling in other memories), to recall good times with someone who was a good friend, and to put out a silent wish: I hope the good life has found you where you are.

It certainly has found me. Coming home—to Billings, to Elisa, to Spatz the cat—is the best arrival I've ever known. It makes the leaving worthwhile. 8/5/2022 0 Comments Great Falls, AdequatelyCome October 1st, it will be six years of marriage and about seven and a half years of togetherness for Elisa and me, and let me tell you: That's long enough that most of the stories have been told, mine to her and hers to me. We scooted away for an overnight trip to Great Falls this week. I had an event at Cassiopeia Books and an overdue acquaintance to make with owner Millie Whalen, and it was nice that Elisa and I could get away, just the two of us, for a little while. On the trip home, one of those untold stories spilled out ... Great Falls is where a lot of my family lore resides—my father, born in Conrad, grew up around there, and he and my mother married there long before I showed up—but it's not somewhere I often go. In nearly sixteen years of living in Montana, I've been only a handful of times, far less often than I've been to Missoula or Bozeman or Livingston or Helena or, heck, Miles City or Glendive. But in 1992, I almost moved there. That's the story that had gone untold. Now, when I say "almost," some qualifiers are in order. I wanted to move to Great Falls (or thought I did). The sports editor at the Great Falls Tribune at the time, a wonderful guy named George Geise, wanted me to move to Great Falls. The man who could make it happen, a senior-level editor at the paper I'd just as soon not name (but whose name I've never forgotten), made it clear I wouldn't be welcome there. The reason: I didn't have a college degree, and he didn't think I was qualified for the job without one. (I still don't have a sheepskin, but that's another story.) Now, let's be clear: This guy was flat-out wrong. I could handle the job I'd applied for (sports copy editor/page designer). I was handling it at a paper of similar size in Texarkana, Texas, and I would go on to handle it at progressively larger, more prestigious papers. I would, in time, become well-decorated and well-traveled. I would lead workshops in editing. I would direct a large sports department at a large West Coast newspaper. I would ... but I hadn't yet. Not in 1992. Then, I was a 22-year-old kid with some talent and, in fairness to the Executive Who Shall Not Be Named, some cockiness that was a bit out of proportion to the skills I'd honed to that point. And that imbalance, I think, would have been a perfectly valid reason for him to say, "Sorry, kid, not going to happen here." But that's not what he said. He fixated on the degree I didn't have. I didn't get the job. George Geise was disappointed. So was I. There was personal history to unearth in Great Falls, and I was already well in love with Montana, an affair that goes on and on. I thought I was missing out on something important. So, stuck for a while longer at a job in Texarkana I no longer wanted*, I made a resolution, one that has stuck for 30 years: No way was a guy like that going to be right about me. I made sure of it. *—In Texarkana, the single most appalling moment of my journalism career, now more than three decades old, happened. When Magic Johnson rejoined the NBA after his HIV-positive diagnosis, I played the story big on the front page of the sports section (as did just about every paper in America). The next day, a copy of the page was in my mailbox, the story circled in red pen, along with a note from an executive at the paper: "Magic Johnson is an immoral HIV carrier, and none of our readers care about him." I should have quit on the spot. It's to my eternal chagrin that I did not. I did, however, start looking for a new job immediately.  Me with Zula (RIP), clowning around in Great Falls in 2007. Me with Zula (RIP), clowning around in Great Falls in 2007. Now ... Did I miss out on something by not finding my way to Great Falls in 1992? Well, yes. Something. But not everything, and not the most important things. I didn't make it to Montana and stick here until 2006, when I was 36. Within a couple of years, I was writing books, something I'd have not even attempted 14 years earlier. By the time I got here, I'd already dug into the personal history that was faintly compelling me in my early 20s. I'd found my grandfather and closed an open question. I'd begun to talk to my dad about his life and his memories, so I could find ways to get closer to him. In subsequent years, I'd help, in whatever meager way I could, to put ghosts to rest. The headstone pictured below on my grandmother's grave (in Great Falls) went in just 15-plus years ago, well after her death, as my father began to forgive her for the ways she'd wronged him, a thawing of feelings that came about because he and I started digging in the hard soil of his past. On some level, I'm just guessing, but I doubt any of that would have happened the way it did if I'd shown up in Great Falls at the callow age of 22 and burned through that job the way I burned through others during that time in my life. Montana might have been over and done with before I could have gotten to know her. I might have missed the best years I've enjoyed here. The very best years of my life, as it turns out.

So far, anyway. This is a story of a bookstore. It's a story of a bookstore that was baked from scratch, with not a lot of ingredients, by a lot of people who'd never baked a bookstore before, trying a method that, if not unprecedented, certainly is uncommon. The bookstore is This House of Books, in the town where I live, Billings, Montana. Its name is a nod to perhaps the most famous work of perhaps the most famous Montana author, Ivan Doig. What we call it is one of my favorite things about it, but not my very favorite. No, my very favorite thing about it lies within the many people who love it and sustain it, and then that smaller set of stalwarts who ensure that it keeps going, who dig deep into their own pockets to give it an occasional transfusion, who pour their sweat equity into its needs, which are both predictable and unpredictable. Who are there for the biggest moments in its life. Like when it moves, as it did this holiday weekend, going from one lovely downtown space to another. Elisa and I offered some modest help with the move, just a few hours and just a few dolly loads. We're part of the larger support system, the people who shop there, who invested early in its co-op model, who take advantage of its generous policy of holding events for local authors. Today, for example, I dropped in for an hour and helped stock shelves (including my own, below). A small contribution. The stalwarts, they'll be there into the deeper hours, as they have been all weekend. Bless them. We would not have this community pillar if not for them. And it is a pillar, a status the bookstore has achieved against what Alex Chilton, in another context, called "unbelievable odds." It's the brainchild of author Carrie La Seur, whose admirable tenacity ensured that we didn't just talk about having a bookstore in Billings but also got it done. Its funding model was suggested by former Billings mayor Chuck Tooley. It wobbled into a standing position on underfunded legs, but it found a way to walk, and it's walking still. That's thanks to talented and selfless folks who volunteer their time and energy. And, of course, it's thanks to the people who shop there.

The continued existence of This House of Books feels personal to me, and not because of the money Elisa and I have sunk into it (not all that much, relatively speaking) or the labor we've done (ditto). No, it feels personal because the bookstore exemplifies the promise and the attraction of where we live. It feels like a stand for the homegrown, the funky, the only-in-Billings, the same as the non-chain restaurants and the little shops and the independent coffee bars here. It feels like something the billionaires and the hedge funds can't get their claws into, if we don't let them, if we consider where we buy and why and act on those values. Downtown Billings was a moribund place for many years, and it's not anymore. I'd like to think our little bookstore has something to do with that. If you've got one—an independent bookstore—cherish it. If you've always dreamed of owning one, feel free to claim a piece of mine. Ours. 6/18/2022 0 Comments Scenes from a GetawayWords from the getaway—four days in North Dakota and the edge of Montana—to follow ... soonish. For now, enjoy the pictures!

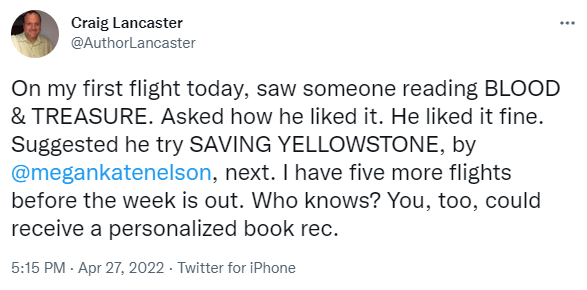

5/20/2022 0 Comments History as I Wish I'd Learned It Several months ago, one of my journalism and writing heroes, Tom Zoellner, invited me to review Saving Yellowstone for the Los Angeles Review of Books. I was a bit cowed by the prospect, to be perfectly honest. I don't have any standing, in senses literary or academic, to critique the work of Dr. Megan Kate Nelson, the book's author. I hadn't yet read her previous book, The Three-Cornered War, which had been a Pulitzer finalist. I was, upon first consideration, well out of my depth and not particularly inclined to take on the assignment. And then I reconsidered. If Dr. Nelson's literary ambition is to peel back history and explain it to a general audience—as well seems to be the case—then I'm about as general as they come. I'm curious and informed, I live in the region where the events of Dr. Nelson's book unfolded, and I try to live my ideal that an engaged life and mind require making some inroads into all you don't know (a considerable pile for me) and challenging those things you think you do know (also a considerable pile). In those ways, I was redeemed by reading and reviewing Saving Yellowstone—and by backtracking to read The Three-Cornered War. The review speaks for itself, I think. Beyond the completion of my assignment, the book has stayed with me. I've repeatedly recommended it, in sometimes obnoxious ways (see the tweet below). I've put it in the hands of friends. I've pondered the way Dr. Nelson's presentation of history—as something connected, something that breathes and reverberates—stands at odds with the lessons of the garden-variety public education I received in my Texas suburb, in which events were stand-alones and dates were to be memorized and regurgitated. Dr. Nelson's book details the Hayden expedition into Yellowstone, yes, and the establishment of our first national park, but also so much more, including the influences of capitalism, the literal and figurative erasure of Indigenous peoples, how the grappling with Reconstruction was not just a southern story but also a western one. One of the jarring lessons of the read, for me, was seeing the way the Grant administration's attempt to bring freed slaves into the body politic lay parallel with a policy of dispossession and extermination of Indigenous peoples in the West. The aims of the former policy largely failed; the aims of the latter were vastly realized. The result of both has been lasting inequality. The book is a triumph of dot connecting, of context, of presenting the bigger picture that lies outside conventional framing. It cannot be read without the realization that the fracture points of yesterday linger today. In the reading, I was reminded of something I often impart to editing clients when I sense that their narrative has gone passive (something that is NOT an issue for the history Dr. Nelson illuminates or the way she goes about telling it). The "and then, and then, and then" structure of storytelling will not compel an audience's attention or investment. I mentioned the polished-up version of history I absorbed and spat out for tests in my youth. That's how it was often (not always, but often) presented to me: Here's this. Here's this. Here's another thing. Here's still another. Hey, why is your head down and what's with all the drooling? Dr. Nelson's book, a work of scholarship, clicks along the way good storytelling does. It has sinew and electricity and a heaping measure of "but therefore ..." It moves. It speaks. It is kinetic. You must read this book. Yesterday, I drove from Billings to Livingston to see a lecture by Dr. Nelson and by Dr. Shane Doyle, who detailed the fascinating history of Indigenous peoples in Yellowstone.

Their presentations were sponsored by Elk River Arts & Lectures and the Park County Environmental Council and served as a fundraiser for the All-Nations Teepee Village, an event "to honor and recognize the many Tribal Nations with connections to Yellowstone and highlight the indigeneity of the landscape." To learn more about that effort (and to donate), go here, please. I've been in Montana for a while now--much longer in my heart than in my physical presence—and every day that has included a trip to Livingston can be filed away under the heading of "Best Days." Beers and yuks with the great Scott McMillion (who wrote the quintessential Livingston appreciation). A quick bite and more imbibing with Marc Beaudin. Chatting with Elise Atchison and Max Hjortsberg and Tandy Miles Riddle. Seeing pals on almost every corner. May your life be blessed with interesting travel and good friends. My friend Caroline Patterson has a new novel coming out Sept. 15. It's titled The Stone Sister, and it promises to be an absorbing, fascinating read. It's getting some fantastic endorsements from the likes of Ann Patchett, Annick Smith, and Kim Zupan. Here's a book trailer: Looks fascinating, doesn't it? Well, go get it.

And while you're at it, be sure to check out Caroline's exquisite new website and learn more about her and her work. 8/11/2021 0 Comments The Trip That Wasn't

I shouldn't be sitting here typing these words.

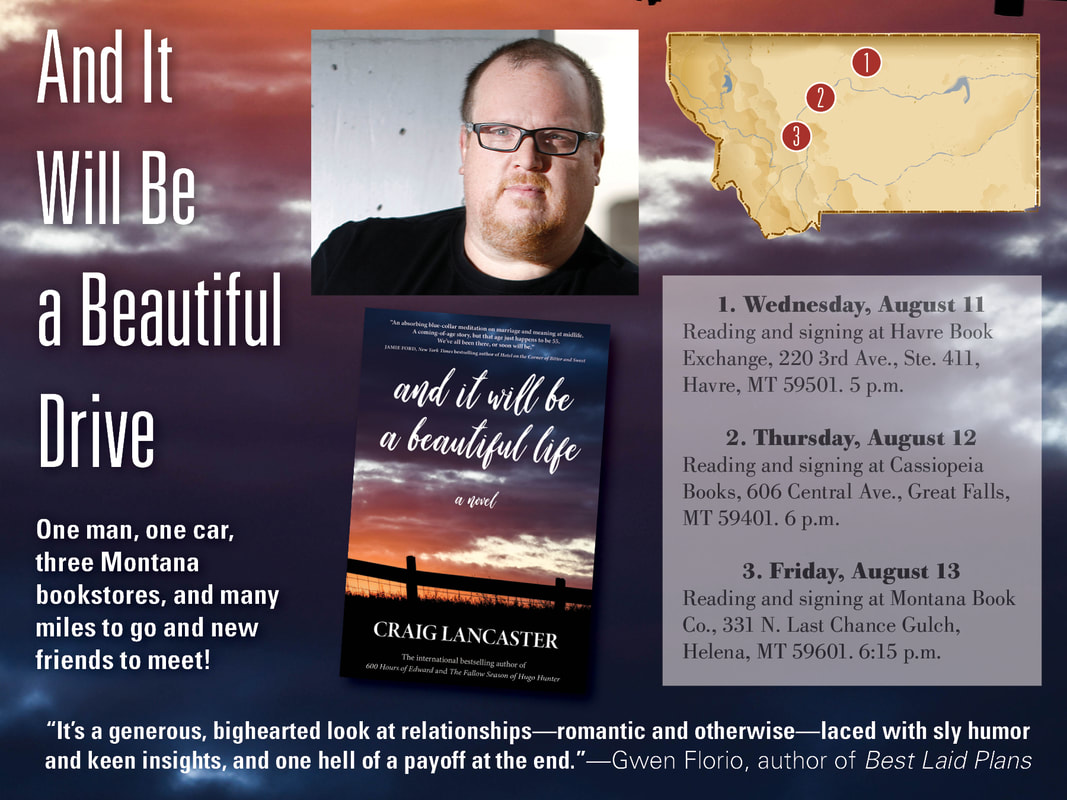

Were plans rock-solid, immutable things, I would be in my car right now, its nose pointed north, my pup Fretless in his bed in the backseat, on my way to a three-day adventure of meeting readers and introducing my new book to new friends. Plans, alas, are not rock-solid and immutable. They are, as Death Cab for Cutie noted*, "a tiny prayer to Father Time." I'll not be in Havre tonight and Great Falls tomorrow and Helena on Friday, making visits to these independent bookstores that I love. In two cases, it couldn't be helped. In one, it could be, but we—the collective we; remember that?—seem unwilling to do what's necessary, a problem that's far, far bigger than my picayune book event.  Fretless after Hospitalization No. 1. That's a good boy. Fretless after Hospitalization No. 1. That's a good boy.

Fretless took ill last week, leading to a frustrating series of escalating vet visits (and costs—oof). The poor little guy gave up first on food and then on water, and when his underlying bloodwork numbers and vital signs were otherwise pretty unremarkable, it all became this weird sort of Occam's Razor guessing game. At one point, the thinking was that he might have atypical Addison's disease (he doesn't, thankfully). Twice, the veterinarians pumped a liter of water into him. He has a pharmacy of meds lined up on the kitchen counter.

Finally, we found the culprit: pancreatitis, which is scary but treatable. He'll be fine. He's already well on his way to that, a welcome sight, but by the time we got our arms around the thing, I'd already canceled the gigs in Havre (Havre Book Exchange) and Great Falls (Cassiopeia Books). I hope we can reschedule, either later this fall with the hardcover or next spring when the paperback emerges. It's been years since I've been on the road with a book, and I was jonesing for this trip. Plans, man. They're tenuous things.

By the time I pulled the plug in Havre and Great Falls, the Helena trip (Montana Book Co.) was already off the board, a casualty of the spike in Delta variant cases. It's a completely understandable decision by the store. Believe me, no one wants live events more than bookstores do. As adaptable as they have all been to videoconferencing and trying to maintain community—the entire foundation upon which they are built—amid a pandemic, they know that there's nothing quite like an intimate gathering of people who love books.

But nothing is more important than safety. Please, get vaccinated. Wear your mask. Do it for others and for yourself. It's been far too long since we saw each other.

* — What Sarah Said

|

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed