|

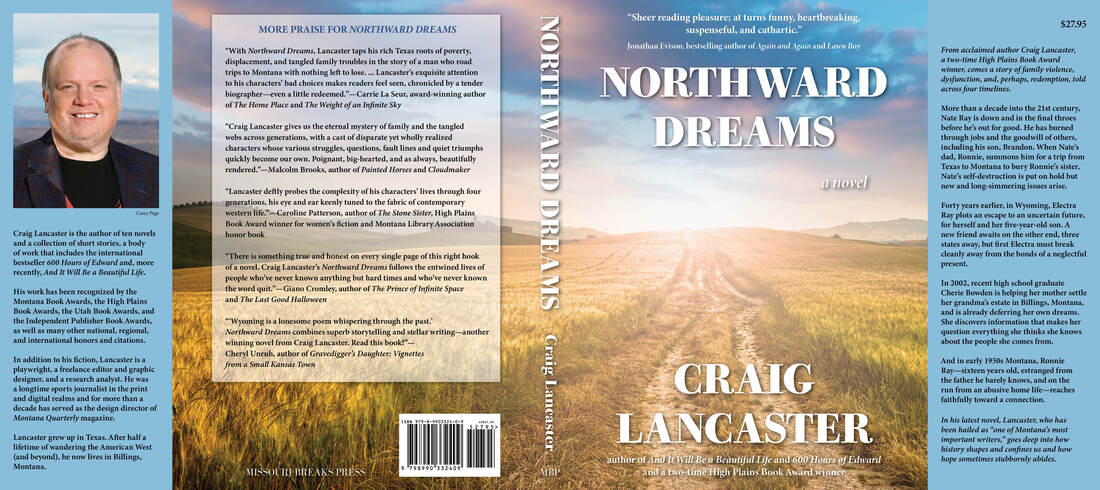

7/13/2024 0 Comments The Vicissitudes of Life**--I used this phrase in my most recent newsletter, and one of my dearest friends wrote me a wonderful email with it as the subject line. Consider this a case of virtuous recycling. It has been nearly two months since I put something new up here. Sorry/not sorry, as the saying goes. So much has happened, and I have so little to say about it, and that's a strange combination. Confronted by this dynamic in the past, I've found it best to turtle up and wait until something worthwhile comes to mind. If you're seeking mindless blather, surely there's a high-frequency, low-content Substack site out there for you. And yet, enough has changed, and enough good intentions have been met with poor follow-through, that an accounting is in order. Let's do this scattershot style: I've moved. But that's not all. Elisa covered this beautifully in her own newsletter, so I'll neither say a lot more nor take issue with any of it. She now lives in New England, her other heart earth, and I still live in Montana, mine. I'm renting space in a lovely old rambling house in my favorite Billings neighborhood, pushing on with life and art. I have a beautiful office setup that is a joy to pile into each morning. My primary work, which I find interesting and fulfilling, continues apace (you can read a piece I wrote for PaymentsJournal here). Fretless and I take walks, sometimes alone, sometimes with my roommate and her dog. I tend to my dad. I have lunch with friends. It's a good life but also a different life, and I think Elisa would say the same thing. Fiction: At a standstill Once I decided to spring Northward Dreams loose from its intended publisher, spring became a blur as I pushed out a retitled, re-jacketed version of the book and embarked on an ambitious series of appearances. Those have largely subsided as summer has come on, and it will probably be fall before I rev up again. The paperback comes out in November, and that's a good opportunity to hit the road again. I had so much fun with the hardcover. What hasn't been fun—and I'm only being honest here—is going through the wringer of publishing, which can be a heartbreaking business. Writing is the best kind of joy—challenging, yes, but also a test of self, of the quality of ideas, of endurance. Publishing...Well, if I can't say something nice, and I can't, best not to say anything at all. It's not like my travails register as important in the larger scheme of things; hell, they're not even all that interesting to me given all the ways the world is on fire (literally). But if I'm going to write stories—and I am—I will have to resolve my attitude one way or another. Right now, I feel three impulses: 1. Forget publishing altogether. 2. Find another partner like the one I just dispatched, something I never wanted to do, and approach the altar again. 3. Do with every subsequent book exactly what I did with this one. Until my heart settles, I'll do nothing. Playwriting: Stay tuned After the final curtain closed on Straight On To Stardust last fall, I set about writing a new play and turned it around quickly. It's called The Garish Sun--know your Shakespeare—and I hope to have some interesting news to pass along soon. #deliberatetease At this juncture, I'm much more interested in and satisfied by working as a dramatist than I am in writing another novel. These feelings, of course, are subject to change (and always do), so I wouldn't read anything into that declaration. Just something I wouldn't have predicted, say, three years ago. Life, man. Let's have a conversation At the beginning of July, I joined at the speaker roster at Humanities Montana. I'm thrilled about this, as a longtime admirer of and sometimes participant with this organization that advances the humanities in Montana's public life. My program, titled Where Memory and Imagination Meet, draws on subjects that have long held fascination for me—the roles of memory as an ignition point and imagination as the building blocks of fiction—but expands the idea to take in such diverse topics as family, background, community, even citizenship. When we talk about our memories of the things that shaped us and marry those with imagining different ways of talking and connecting, great things can happen. My program, like all the others sponsored by Humanities Montana, is available to schools, libraries, civic groups, and other such gatherings. Information at the link above. If you have a group in Montana that would benefit from this conversation, let's talk! Yeah, but what about all the other stuff? Oh, you mean Craig Reads the Classics? The Saturday craft talks? General keeping in touch?

What can I say? I've been quiet lately. But I'll be back. That's a promise.

0 Comments

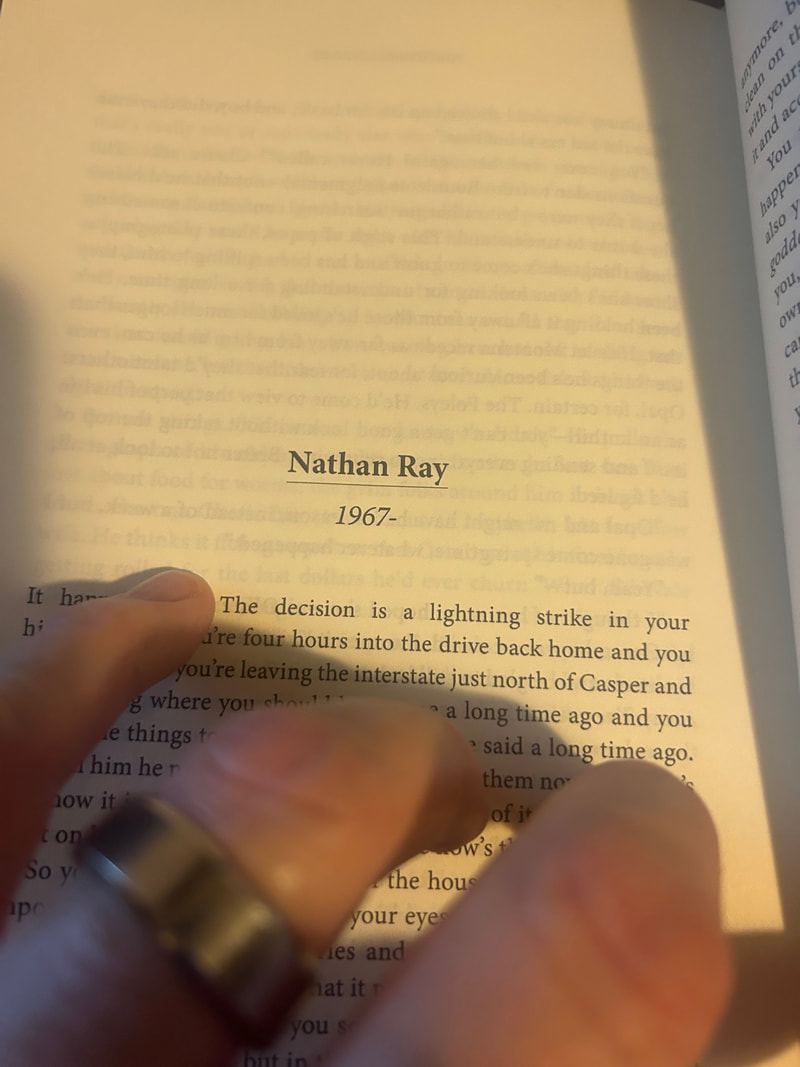

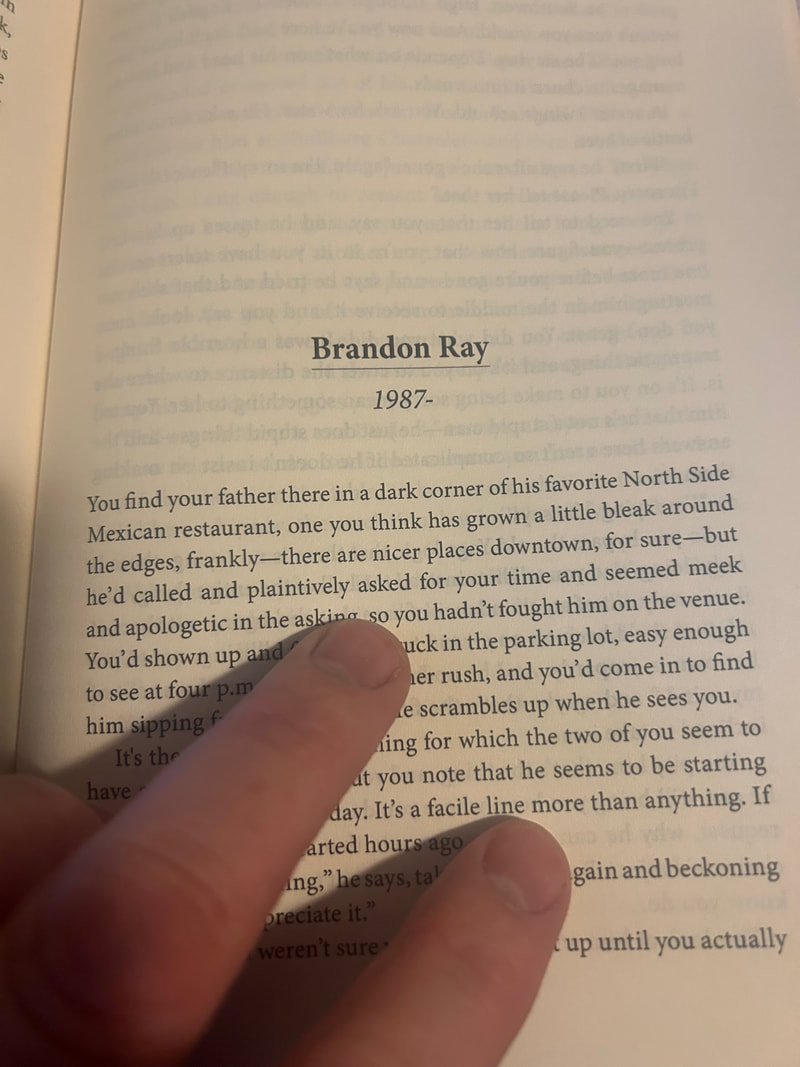

We've been headed here all along, haven't we? The book's first full chapter begins with Nathan. The book's last interceding chapter ends with Nathan. He stands as the pivotal character in an ensemble, the one who can still change his course, if only he has the courage. Others have made their choices and lived, or died, with them. A lot is behind Nathan. More could yet be ahead. There's not much else I want to say, except this: For me, the suggestion of future change is the most satisfying part of literary characters. I'm far more interested in the idea that they could change than the actual shape and scope of that change. It's why I like open-ended endings so much: Presumably, life goes on, until it doesn't. While we're sentient and breathing, it's within us to deviate our path. Thanks for reading. (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) PreviouslyOf these nine timeline-busting chapters—just one to go after today—this one is the anomaly. It features a character who never appears on camera, as it were. Brandon Ray, son of Nathan, grandson of Ronnie, interacts with his father in phone calls that are clipped, distant, and loaded up with tension. And yet, he's essential, in that the book traffics heavily in fathers and sons and what gets passed on and where the fault lines lie. Brandon and his father are mirrors and opposites, a dynamic that also follows daughter (Cherie) and mother (Anna) in another timeline. Brandon was largely raised by another man—quite successfully, Nathan knows, and that's a source of pride and an unwanted memory, given his own path. And there's something between them—something bigger and more immediate than their shared past—and in this chapter Brandon lays out the choice the older man has in the matter. It's in the book. (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) PreviouslyOne of the interesting things about human development—to me, at least—is the occasional alignment with physics in the equal-and-opposite-reaction sense. Cherie, the centering character of the 2002 timeline in Northward Dreams, is uncommonly wise and strong for her age. Her mother, Anna, provides some of the underpinning for these qualities through her frailty and failures. Together, they make for a compelling pair. There's love and genetic bonding and deep care and frustration and exasperation. Cherie exists because Anna created her. Cherie is who she is, in part, because she must compensate for her mother. That's a hard road. Anna's inserted chapter arrives fairly late in the entire span of the book. She has made a fateful decision, the kind we don't get to walk back once it's in place. There's not a whole lot more to say without saying too much. You should read the book. (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) Previously

I'm going to tell this story only once, for posterity, perhaps, or maybe just because it's so bizarre that I'll want to have this record in a year or 10 years or 20, when I won't remember the fine details anymore.

Soon—very, very soon—my 10th novel will be out in the world, available in a variety of formats through just about any retailer that sells books. For the longest time—and that's part of the story, really, the loooong time—my assumption was that it would be called Dreaming Northward and would be released by the publisher behind my previous book, And It Will Be a Beautiful Life. We had a good relationship, this publisher and I, and I expected our association to go on and on, to the end of my career. But it didn't go that way. On March 11, the day before Dreaming Northward was set for a fractured release, with the e-book going out first and the hardcover and audiobook supposedly to follow at some ill-defined point, I asked the publisher to cancel the book and immediately revert all rights to me. (That request was granted, for which I am grateful.) I will not engage in a blow-by-blow description of all the ways I believe my trust and faith were compromised. And I have no desire to harm this publisher; indeed, despite it all, I have great affection for the guy running the operation and would even consider a return if certain factors that beleaguered this book were dealt with and overcome. Obviously, the publisher might not be interested in a reunion, given the events of the past week. I'm just being clear about where I am on this. I'm not mad. I'm not even hurt, not really. I'm just sad and disappointed over the outcome but also resolute that it had to happen. Dreaming Northward is gone. Northward Dreams lives.

So why did I do it? It's not like publishing contracts are easy to get. It's not like I'm a well enough known quantity that I can act like a spoiled child and get away with it (or even foment the impression that I'm a spoiled child). It's not like I have this notion that independent publishing is a dream trip. I've taken it, and it's not. It's a slog. It's exhausting. It's an endeavor undertaken with the odds ever against you.

So first, let me say this: I'm a lot of things, but I'm not a spoiled child. Second, I've been around enough publishing blocks—self-publishing, small publishing, big publishing with powerhouse marketing and backed by big-time agencies, etc.—to know that almost everything is a crapshoot for almost everybody. In this case, the promises made to me about how my book would be positioned and the marketing muscle that would be put behind it were, in retrospect, dependent on a round of funding my publisher kept promising was imminent, month after month after month. After this book slid from its original publication date in June 2023 all the way to the doorstep of last fall, I asked for a Spring 2024 date, thinking that might provide the necessary buffer for the funding to come through and for the marketing pieces to be put in play. Many, many times, I was told the funding was just a signature or a courier away from being realized. Month after month, it didn't show up. In late January, I asked if the March 12 release date was going to hold. Yes, I was told. But in the end, that cratered, too. The e-book was definitely going to come out, but the hardcover would have to be delayed. That was the eventual word. How long would the delay be? No one could say. I wasn't comfortable, but I was willing to go along and have faith. We were so close. Then came March 11 and word of another funding delay, and that ended my faith. I couldn't trust that the hardcover edition would ever come out. The more I considered it, the more I feared that the e-book would get launched, nothing else would come up behind, the whole thing would eventually crash, and I would have to pick up a barely breathing book and try to resuscitate it on the fly. It was just a bizarre episode. Not two days before I asked for a reversion, I stood in front of 50 people at the Billings Public Library, talked about And It Will Be a Beautiful Life (the most recent selection for the One Book Billings community reading program), and premiered a video about Dreaming Northward. (The video has been edited in light of recent events and can be seen below.)

I had every expectation that my book release, flawed as it might have been, would be realized. Then Monday dawned, and with it came another funding delay and my publisher's declaration that he was leaving his post for a couple of weeks amid this latest setback. He said he had to shore up his affairs in light of the situation. That was the final blow to my trust.

I asked for my book back. I made arrangements to publish it myself, through my own boutique house. In a frenzied 24-hour period, I conjured a new title, designed a new jacket, got hardcover files together and uploaded, got the e-book file to my designer, revamped this website, reworked marketing materials (such as Facebook headers and event posters), contacted booksellers and librarians who have already booked me, and, somewhere in there, bagged a few hours of sleep. Just last night, I approved the hardcover files with my printer/distributor and officially set a publication date: March 19, 2024. As I said on Facebook: I lost a week. I gained my whole book. It's not remotely what I anticipated or wanted. But it's my project now, and I'm determined to push it as far as it will go. I'll have to do some fundraising. I'll have to come up with some clever and creative marketing approaches. I'll have to look for people to say yes. Bring it on.

So the e-book comes out first. What's the big deal?

Look, I love e-books. That's how thousands and thousands of readers have been exposed to my work. But my passion lies in supporting independent bookstores, and this was always going to be a bookstore book. There were grand plans—personal letters to booksellers from my publisher and me, flashy campaigns through Bookshop.org, maybe a tour. All dependent on funding, of course. And it wasn't so much that the e-book would go first that bothered me as the fact that I no longer believed the hardcover would appear at all, given the dead promises along the way. There was no way to be OK with that. My faith was expended. That doesn't mean I wish bad things for my old publisher now that my book is out of the mix there. On the contrary, I hope I'm extraordinarily wrong about my suspicion of how that situation will finally play out. I hope he calls me in a few months and says, "You should have waited, buddy boy," and sends me videos of his lighting cigars with hundred-dollar bills. I'd be thrilled for him because he's a good man, and he was hands down the best editorial partner I've ever had. Publishing is hard work. It's even harder on a shoestring budget (as I well know and am about to experience again). I don't hold my publisher's inability to do right by this book against him. He was trying. Hard. But it wasn't happening, and in the face of that reality, my loyalty had to be to my work. In short, even if my publisher's highest ambitions come to fruition, I made the right call, given the track record. At the moment I had to make a decision, I made what I consider to be the brave one. I chose my work. I chose my sense of integrity. "If it's not hell yes, it's no" is a great clarifier in matters of choice. Sticking to that rubric, even when the answers aren't easy and even when the wish is for a different outcome, can keep one from committing reservedly to something that requires one's whole heart. I was no longer at "hell yes." Therefore, it had to be "no." 3/2/2024 0 Comments Q&A: Chérie NewmanToday, it's my pleasure to host one of my all-time favorite human beings, Chérie Newman, as she answers some questions about her book Other People's Pets: Critters, Careers, and Capitalism in Yellowstone Country.  One of the things I like best about Chérie is how deeply she thinks about things, a tendency of hers that is written across her answers to my questions (and I promise, we're getting there soon). Then, of course, I'd have to consider the other things I like about Chérie, and the list grows. She has wide-ranging talents, she's a supportive pillar of the culture she exists in, and as I know from personal experience, she'll drive a few hours to see your play. (Well, maybe not yours. But mine. Thanks again, Chérie!) I've known her for going on two decades, and I'm continually impressed by the breadth of what she dips into and becomes proficient at doing. Without further ado, then, here's Chérie Newman and her thoughts about Other People's Pets...  I'm fascinated with the resumption of your—not career, really, but work—as a pet sitter after a long break from it. What prompted that? Was it like riding a bike, as the saying goes, or were there rigors to the second go-round you didn't anticipate? The resumption of my work as a pet sitter happened during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Before March of 2020, I earned most of my freelance income as a podcast editor, working with audio files recorded during live events. Then, suddenly, there were no live events. No live events meant no money for me. My hasty reaction to the loss of income was to accept a job as an office manager. Yuck!! I do not like office work. So, I quit that after a year and agreed to become a subcontractor for a Bozeman pet sitter who had way more work than she could handle. This was the end of 2021, when many people were starting to travel again. She started sending me on interviews and that’s when the fun began. Although, I’ve taken care of other people’s pets all my life, it was mostly for friends and family. Right now, I can only think of four or five people—“clients”—who hired me as a professional, home-stay pet sitter between 1990 and 2022. The rigors, as you say, of these new situations were complicated and multi-faceted. Most of the people I worked for were nice. But they weren't paying a lot, and their expectations were high. And, I have to say, that even though they were paying me two or three times the amount I’d earned before, the average hourly rate came out to about $4 an hour. Four dollars an hour for being on duty 24/7 is not great. Especially when you factor in responsibilities for other people’s property, package delivery (Why do people order stuff when they know they’re leaving town?), invisible fences that fail and other high-stress events, and the fact that most of the houses were located far from central Bozeman. The $4/hr didn’t include fuel and other travel expenses. It didn’t include travel expenses incurred when I drove 30 miles for an interview. At what point did you realize you were gathering book-worthy material? When my friends started yelling, “You have to write a book about this!” every time I told stories about my experiences at dinner parties. I love how the book uses something as seemingly picayune as pet sitting to explore much deeper themes about where we live and how. What are the big takeaways for you regarding our relationships with our animals and the places we call home? Well, first let me say that I’ve noticed a trend: pets are now treated more as children than animals. The love-of-my-life dog, MooJee, lived with me for 15 years, but I never considered her my child. She was a beloved companion and, of course, I did everything I could to keep her happy and safe. She was dependent on me for that. But. She. Was. A. Dog. During my recent pet sitting adventures I noticed an increase in bad pet behavior. Lots of neurotic animals, made so, I believe, by their people. For example, I took care of two Irish setters whose daily schedule included cocktail weenies at 4:30 p.m. and an 8 o’clock bedtime. They also expected their lunch at 2 p.m. and acted out if it wasn’t served on time. By acting out I mean behavior such as opening the freezer and letting food thaw or dragging kitchen scraps out of the sink and throwing them all over the floor or hiding car keys under a dog bed. The places we (some of us, anyway) call home seem to be much more temporary than they were in the past. And people who have more than one house/home often leave their animals with a pet sitter while they live somewhere else for long periods of time or take pets with them and leave their houses empty. I wonder about all the huge, often uninhabited houses standing on Montana land, places that used to support wildlife, land upon which wildlife can no longer migrate or find food. What have you learned about humans through their pets? I’ve noticed an increase in the human need for external approval, which some people try to extract from their pets. Kind of crazy. Pet pics on social media attract lots of attention, which offers online validation for people. But of course, pet pictures and stories are entertaining and fun. We can’t safely post images of children online these days. Maybe our pets are stand-ins? And then there’s the amount of money people in the U. S. spend on their pets—nearly 150 billion dollars in 2023, according to Market Watch. So, your question is insightful. Are humans devolving as the status of pets rises? Are pets usurping control of our behavior and finances? What's next for you (wide-open question; I'm talking books, music, vocation, avocation, etc., etc.)? Ha! Thanks for asking. My mind is always blazing with new ideas. I just published another book, Do It in the Kitchen: a step-by-step guide to recording your life stories (or someone else’s). When they find out I’m an audio producer, people often ask me questions about recording audiobooks and oral histories, or want to know how to create a podcast. This book will help anyone who has those kinds of urges. I just finished writing a children’s book about a dog who saves his family from a house fire (true story). The process of finding an illustrator has been, well…interesting. I wish I had better drawing skills. (But maybe not because then I’d draw and I have too much other stuff to do.) My list of podcast clients has grown again during the past few months, so I do that editing/production work as it comes in. I’m also a musician and play in a band called Ukephoria Montana. We perform public and private concerts and participate in twice-monthly sing-along sessions at the Gallatin Rest Home. I participate in a songwriting collaborative and write songs on my own, as well. Every so often, I land a public speaking or workshop facilitator gig. I can’t name names, but I’m talking with an educational group about the possibility of producing a podcast series for them. It would be a dream gig for me. All fingers crossed, please. Since I’m self-employed, the marketing and PR tasks are endless. There’s always something new to learn. And, oh yeah, I read a lot of books and listen to several audiobooks a week. Yep, a week. Recent favorites:

What am I missing? What else would you like to say?

Oh, you are a brave man. I always have something else to say and usually say way too much. But I’ll stop now, except for this and this:

Wait! One more thing: Thank you for these questions and for reading my book. Oh, and another thing: I’m champing (yes, champing — to more precisely convey “impatience” — not chomping) at the bit to talk with you about your new novel, Dreaming Northward. Okay, that’s all my things. Maybe. But you should stop reading now. 2/19/2024 2 Comments Like Planes on the RunwayI suppose this could be a Saturday Morning Craft Talk, except it's not Saturday morning* and it's not particularly crafty. So scratch that. No. No, it couldn't. It does, however, speak to an aspect of the writing life, one that varies wildly from writer to writer, if my conversations with colleagues and contemporaries are any guide. What does one do with the ideas when they're not actively being worked on? It's a good question, one with a slapdash answer for me. I'd love to be a capital-letter Artiste, with a leather-bound notebook that never leaves my side, with stacks of brimming journals, with a catalog of every thought I've ever had and a handwritten account of every beauty I've ever witnessed. Alas. I'm just a guy with a brain, such as it is. My ideas—what I've thought of doing, what I'd like to do, what I'm considering, what I've started and not finished, etc.—are all in there, in some stage of marination. It's no doubt a terribly inefficient system, but I'm not complaining. I wrote my first novel in 2008, a breakthrough that came after years of wanting to and not really knowing how. Since then, I've not lacked ideas; indeed, I often describe my notions as being backed up like planes on the runway. But an archivist, I am not. Nor an inventory specialist. Nor a tour guide. Whatever I will or might do is up here—*taps head with index finger*—and I'm the guy with the key. I'll take the key, and the ideas, with me when I go. And that will be that. I've written before about the linear way in which I work—start at the beginning, then write straight through until the end, if I can get there. (I've also written before about how that linearity is subject to the needs of revision, when I'll happily move things around, delete things altogether, or augment the bits that aren't quite cooked.) This, too, is a terribly inefficient system, in that my early days of writing fiction were marked by a sense of loss and bewilderment when a manuscript just didn't go. I'd stash whatever I'd managed to do on a hard drive somewhere, nurse my wounds, shake off the disappointment, then try again with another idea. Fortunately, a new one would be at the ready. Planes and runways and all that. Those half-baked attempts, tucked away in their little folders, were dead things I couldn't bring myself to bury, even though I knew I wouldn't resuscitate them. A few things got salvaged for other purposes--Somebody Has to Lose, at 14,000 words my longest short story, is one such reclamation. But mostly, they take up computer memory and lie dead and crumbling. This used to bother me a lot, just from the standpoint of industry: All that work for nothing. All those words expended and nothing tangible to hold. Boy, was I wrong.  For one thing—and apologies for such a hoary cliche—there's a lesson in every failure, and not every failure is what it seems. This would have come as quite the surprise to the me of 15 years ago, who upon breaking through and at last writing a novel thought he had figured everything out. I didn't know anything. If possible, I know even less today than I knew then. Or I simply know different, better things. For instance... I've learned to wait on it. The manuscript that became And It Will Be a Beautiful Life came out slowly amid several stops and starts, and over the course of a few years. I started it in Montana, pecked away at it in Maine, and found my way through, at last, upon returning to heart earth. It wasn't entirely a function of geography, though I'm convinced that had much to do with it. I simply had the patience to wait for the memories and the imagination to steep properly. That's age. That's experience. That's trust. That's love. A while back, an artist friend introduced me to a well-known author with this: "Craig is a book-a-year guy." True once, but not so much anymore. As a less experienced novelist, I wouldn't have trusted myself to wait for the right idea to emerge in its own time. I wanted, needed, to write the next book, and quickly, if only to prove to myself that I still could. Today, I have no such worries. I know I can do it. I also know the idea I should be working on will let me know when it's ready. Giving it time and space to bloom is granting myself grace in the bargain. I'm increasing the likelihood that I'll find my way through because I'm letting the thing come to me instead of stampeding it. So, about the planes and the runway...

My next novel is just a couple of weeks from being released, the idea having germinated and taken root and blossomed nicely. The one likely to be next is written and ready for the publishing gamut, and that took me the better part of a decade, start to finish. After that? Planes on the runway, baby. I have three manuscripts in various stages of development. I suspect, but don't know, that all will find their way to the finish line. (Big disclaimer: If I have enough time. I've reached a time of life when I worry less about the ideas and more about whether I'll be around to snag all of them.) I'm enchanted with all three stories, but it's not time to finish any of them yet. Soon. Eventually. I trust the process, if not the clock. At long last, I trust the process. *--It's Monday afternoon. Thanks for the long weekend, presidents. 1/7/2024 3 Comments Sunday Morning Craft Talk*

*—if you'll indulge me.

Let's talk about sentimentality. The hook for this is simple enough; just yesterday, I posted something old/new at The Short Story Project: a 2011 story of mine called Comfort and Joy, which appears in my collection The Art of Departure. In the blurb that accompanies the post, I described the story as "unabashedly sentimental," which it is, then I proceeded to be bothered by that description for the next few hours, until I sat down to write this.

Why was I bothered? Perhaps because sentimentality is not highly regarded as a quality of serious fiction. While I'm fairly solid in my commitment to not caring terribly much what someone thinks of me personally—within limits, of course, my being human and all—I do get a bit crinkled when my work isn't taken seriously. See again: being human and all. Let me be clear here: I'm not holding out Comfort and Joy as some superior work of art. It's not. I haven't read it in years, but I know where it fell in the course of my fiction-writing career (early), and I'm certain that if I looked at it again, I would see much I wanted to do differently were I given another shot at it. But for better and worse—tilted heavily toward better—there are precious few do-overs in publishing. Mostly, you do it and live with it. I can live with Comfort and Joy. Its primary strength is this, more than a decade after it was written: It is precisely what I wanted it to be. I am taken with Capra-esque cinema, and I set out to write a Christmas story that captured a similar feel: an isolated old man with a compelling but obscure backstory, a little boy burdened by loss, a mother at loose ends, and the unlikelihood of their forging connections with each other. Happy ending? God, yes. Essential. Like George Bailey being rescued by the people whose lives he made better. Like Clarence getting his wings. Comfort and Joy hit every note I wished to play. Can you occasionally hear my fingers on the strings? Quite probably. But that's a limitation of the craftsman, not a failure of the story. One of my all-time favorite quotes is this one from Roger Ebert: "It's not what a movie is about, it's how it is about it." So it is with any artistic endeavor, I believe. Did you, the artist, do what you set out to do with the work? Yes? Congratulations! You've found success. What other people think you ought to have done is beside the point. Let them write their own stories if they feel so strongly about it.

My intent here is not to launch a spirited defense of my own work but to pose an essential question: If art is about the human condition—its variables, its beauty, its ugliness, and all the imaginable in-betweens—how can sentimentality be relegated to the outside of that? I'm not talking about the glorification of treacle or granting myself free rein to load up stories with so much sugar that readers' teeth fall out. I'm talking about acknowledging a human yearning for sentiment, a human response to what is stirred up in its wake, the emotional outlet it supplies. To my mind, it's rather like humor, another quality often underplayed and undervalued in so-called serious literature. Zaniness may not carry the heft and complexity of irony, but it damn sure offers a compelling reflection of humanity as I know it and aspects of human beings as I know them.

Finally, let's talk about happy endings.

There's little upside to being scholarly about my own work—let me acknowledge that before I say this next bit—but if my stories demonstrate anything, it's that the narrative and the pages eventually end but the story never really does. Think of Edward Stanton looking across the street or Mitch Quillen driving home to his kids, or, more recently, Max Wendt waiting to find out where the flow will take him next. There's so much story beyond the page, and my particular way of writing often compels me to put the responsibility in readers' hands when my words are expended: It goes somewhere from here. Where do you imagine that is? I love doing the same with the stories I'm told. George, the richest man in town, isn't going to jail or being run out of town on a rail. Is Potter? Will Nick someday move along and open a more rollicking joint for men who want to get drunk fast? Do George's kids eventually get out of Bedford Falls, the way he wished to, and will he encourage them in the way his own sainted father encouraged him? It's up to me. What a great privilege.

So, in my unabashedly sentimental short story, the ending comes as the old man stares out of a broken window and beholds unfettered joy. But the lives inhabiting the story, presumably, go on, into other days and moments, into other happinesses and heartbreaks, into gains and losses and despair and redemption. Experience enough of those things and you just might become sentimental about them.

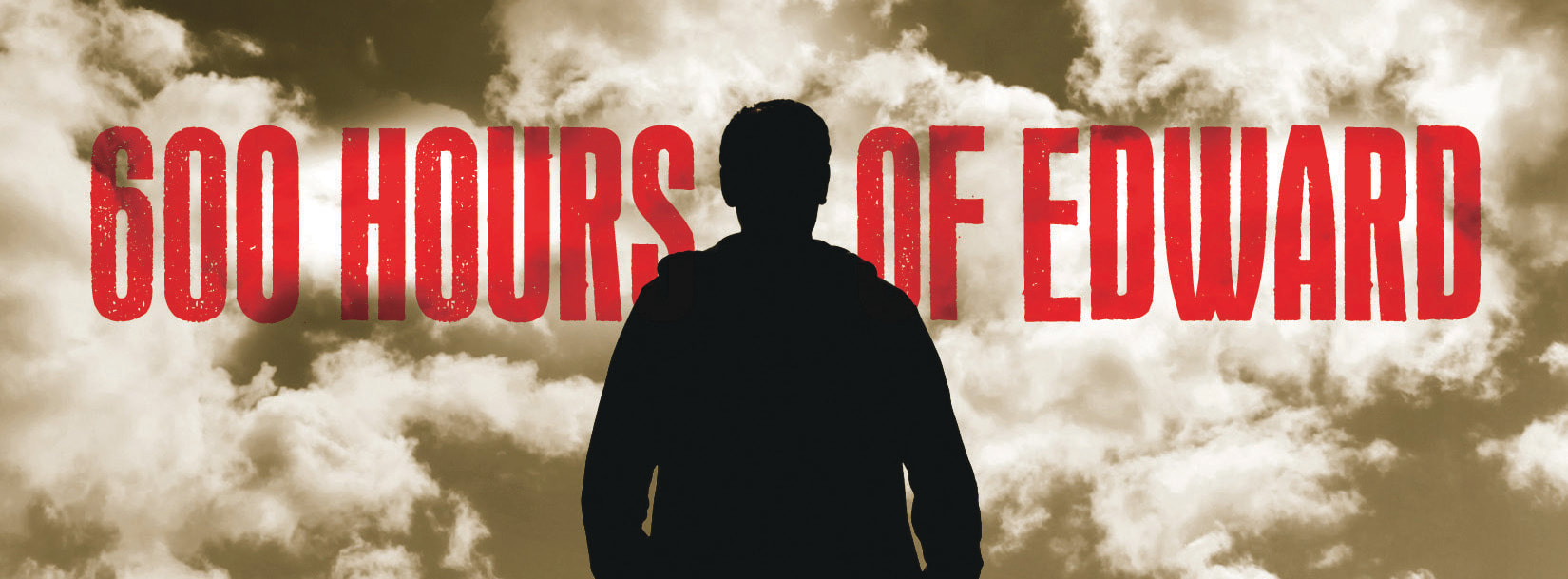

12/15/2023 0 Comments 'It's Not the Trophy. It's the Game.'The title here is paraphrased from something I saw on LinkedIn. (For a whole different view of how I spend my days, hit me up over there.) It resonated for a couple of reasons. One, it was a different wording of an old concept, and that's always appealing. Second, and more important, I was a day removed from a six-hour stretch of standing in front of high school classes and talking to kids about the writing life. (Quick side note: Whatever your talents, whatever your field(s) of endeavor, I cannot recommend classroom visits highly enough. It's a chance to contribute, to give a teacher a much-needed respite, and to help give shape to students' possibilities beyond the classroom, a time that is coming up on them quickly and for which they're probably not fully prepared.) During my visit, I would start by introducing myself to each class and saying, yes, I wrote the book you just read (in this case, 600 Hours of Edward, which is on the approved reading list for Billings high schools), but I also do other things. At the time I wrote 600 Hours, I was a copy editor at the Billings Gazette. Later, I was a pipeline inspection specialist (a fancy title for pig tracker). Still later, I was a senior editor at The Athletic. Now, I'm an analyst for a research firm. I design Montana Quarterly magazine. I take on freelance editing and design gigs that interest me. I write novels and plays and sometimes even poems, although those are mostly bad. Those are a lot of different things, but they share one key commonality: They're not just ways to make a buck. They are things I do and things I am, and that manner of describing them is something I trot out regularly, because it's such a complete summation. That intrinsic sense of purpose and being keeps me focused through the vicissitudes and drudgeries of a workaday life. That work, whether for a salary or for the variable and uncertain recompense of royalties, can't just be about making a buck, necessary as that is. I told the classes that, yes, of course, I sometimes find myself wishing I had more time for the creative things I do. But the truth is, I would miss the payments analyst part of my life if I gave it up every bit as much as I'd miss the toil of writing a novel if that fell away from me. It is at this point that I diverge from some of the artists I admire most, who talk about the art-centered life in almost monastic terms. Or maybe I just use a different definition to arrive at the same idea. Art is at the center of my life, in that there would not be a life worth living without it, but it shares that space with myriad other things that constitute who I am and how I engage with the world around me. So ... the trophy and the game. Some people don't think they've made it until they've made it: until they've reached some perch, garnered some award, ascended to some income bracket, been elevated to some stratosphere. And, in some cases, reaching those levels is the test case for happiness. I think that puts happiness—a transitory quality anyway—in a narrow, often inaccessible place. The game—the process, if you will—is where the action is. Play the game hard and faithfully, however it's defined, and the trophies have a way of either showing up or making a subtle reveal of themselves as something you never imagined they could be. 10/12/2023 4 Comments Closing the Loop: On EndingsThis, I suppose, could fall into the category of a Saturday Afternoon Craft Talk, except it's Thursday afternoon and I don't much feel like being bound by time. We're coming up hard on the first of November, and that will mark 15 years since I began writing my first novel, 600 Hours of Edward. The backstory of how that book came to be is oft-told, no repeats necessary. I will say simply that it was not only my first novel but also the first book-length manuscript I ever finished, which marked something of a watershed by showing me I really could finish something of that size. Before then, I'd always had hope, which is something, but it's far less durable than evidence. I'd like to say I learned something important about how to write a novel by completing that first literary marathon, but I'm not certain that's the case. If you're trying to stretch yourself and grow thematically and ambitiously—and I certainly try—you quickly learn that each new project is a distinct challenge, with its own factors that are highly distinguishable from those that influenced previous works. I suppose that earlier quality, hope, has been replaced by faith, in that I know I've done it before and can do it again. I'm less apt to be cowed by things like hard sledding or the great murky middle, when I'm adrift in a manuscript and not yet sure how it's all going to resolve. But each project rises and falls not on past performance but on indicators I've learned to wait on: the spark of memory, the hard-bond connection to it, the imagination that gets set free, the impossible-to-ignore compulsion, at last, to sit down and start writing. Consequently, my occasional opportunities to talk to aspiring writers about how to go about tackling a novel tend toward mundane platitudes: 1. You have to start it. 2. You have to keep at it. 3. You have to bear down when it gets tough. 4. You have to keep going. Point is, I'm not gifted in the ways of teaching writers. I figured out what works for me, and even then, my success rate falls well short of 100 percent. Not everything I start gets finished. Not everything I finish is worth publishing. It's just the way of things. As for my flaccid advice above, it is, at the least, accurate. You can't write a novel unless you start writing a novel. But let's look at the other side of it: You can't finish one without ending it, either. My favorite moment in the process of drafting a novel comes fairly late, when at last I see not only where the road ends but also a clear view of how I'm going to get there. When, exactly, this moment comes is variable. Sometimes I see it from the distance of thousands of words and have to buckle up for a long ride to it. Sometimes I don't see it until I'm almost on top of it, rather like rounding a bend and seeing your destination city laid out and sparkling before you. Whenever the moment comes, it heralds an important development: I'm going to finish the first draft of this thing. First drafts lead to second drafts, which are my favorite part. That's when I find out whether this thing I've done is worth a damn. I've never made much of a secret of this: I often know how a story will end before I write the first word of it. Now, I'm not always right. But I often am. In the case of 600 Hours of Edward, I knew every word of the last line before I wrote any of the other 70-some-odd-thousand words that precede it. And sure enough, when Edward got there, the ending I envisioned was waiting for him. I had no expectation that such a thing would happen again—hell, I had no expectation that there would be a second novel—and that lack of assumption has served me well in the inevitable cases of endings that never come because I can't get out of the muck and arrive at them. But it has happened occasionally, a function of cinematic thinking, I believe. When I write, I'm also cueing a movie that never gets released and plays for an audience of one: It's an interior visual guide to the look and feel and tone and quality of the story I'm trying to write. Even when Edward was just a flicker of a thought, I could see an ending for him. The struggle lay in getting him there. I had no idea how to do that. That's the voyage of discovery that makes the whole undertaking worthwhile. Here, then, are nine novels' worth of endings (I'll leave the ending of Dreaming Northward to you, sometime this coming spring), along with any interesting (or not) details about them (click the covers to learn more about the books):  "All I have to do is look both ways and cross." As I said above, these were the 11 words I knew when I began to write Edward's story on Nov. 1, 2008. What the rest would be was a delicious mystery that I hoped I could solve.  "And still I wondered: If my children someday learn my secrets, what will they think of me?" I'm not a father (except of pups and kitties), but a couple of times, I've had to find my way with a character who is. Mitch Quillen was speaking clearly to me by the end of that book.  "I know she is." Despite Edward Stanton's love of language, my dude tends toward the simple observations. In the second novel featuring him, he ended with brevity. I didn't see it coming.  "I know this much, too: Never again will we keep our hearts waiting." I'm going to say it: This one remains a little cryptic, even to me. But sportswriter Mark Westerly said it with such finality that I had to trust him.  "His son moved closer, almost imperceptibly, and then, in an instant, fully there, and Samuel slipped a hand across the older man’s shoulders, and Sam leaned into the warmth of his child and waited and hoped for the despair to pass, as all things surely must." I got nothin'. Didn't see it coming. I love open endings, and man, is that one wide freakin' open.  "That’s a fact." Hi, Edward. Of all the characters I've written, he's the least like me but also the one who speaks most unmistakably to me. Will I write him again? If he demands it, absolutely.  "Can you believe that?" Out of context, it's a little hard to catch the nuance of what disgraced and defeated newspaper editor Carson McCullough is saying. It's pure incredulity, a good sign for his life beyond the page, I think.  "Be the ripple." As it turns out, this was Elisa's line, and I think it's just perfect. She, in fact, was the one who recommended ending the story the way we did; I'd had a different, lesser idea. Collaboration for the win!  "Even without doing the math, Max could see so many ways all of this could flow." I knew where the story for Max Wendt would end. (Max, in my opinion, goes on and on beyond the strictures of the book.) But I didn't know the words until we got there and found them shimmering on the Maine seashore. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed