|

2/3/2024 0 Comments Texas.I moved to Texas when I was three years old. No one consulted me, and I wasn't happy about it, but Texas and I, we found our way. In time, I came to view that move as the most consequential event in my life. When I left Texas for the first time, I was fifteen years old, about to be a sophomore in high school, and I made a snap decision that I'd like to live with my father in rural New Mexico. He'd just been through a divorce, a particularly bad one, and I thought maybe he needed me. It didn't take. A lot of lessons in that, some that got under my skin immediately and others that steeped for many years before I understood. Among the latter group, probably one of the most important lessons: You can't fix for someone else what he must mend on his own. By the end of December, I was back home in North Texas, where I belonged, even if I still felt the fit was a little tight. When I left Texas for the second time, I was twenty-one, and I pointed my nose toward just about the farthest-away dot on my map. I went to Kenai, Alaska, for a sports editor's job. That didn't take, either--though some vital friendships did—and I came scurrying back not six months later. When I left Texas for the third time, I was twenty-three, and it was a job I left behind, a fairly miserable nine-month stint in Texarkana. Texas and I, we were living together uneasily amid irreconcilable differences. I worked at night on the Texas side, then hustled back across the line to Arkansas to set down my head. When I had a chance to leave Texas, off to Kentucky I went. When I left Texas for the fourth—and, as yet, final—time, I was thirty years old and adrift, in the midst of one of those Worst Years Ever that seem to surface every decade. I'd bounced from San Jose to San Antonio, and I'd found Texas to be what it always had been: inscrutable, beautiful, alluring, interesting, and not for me. Back to San Jose I went, but first with a three-month misdirection in Olympia, Washington, and it's like I said: bad year. This is all to say that I've left Texas a lot. But Texas has never left me. The math doesn't lie. Texas had me for most of eighteen years, then nine months, then eight months. Nineteen and a half years, let's call it. Add in various visits over the years—can you really leave a place that harbors your parents and your siblings and your formative memories and some of the best friends you've ever had?—and the total still falls short of twenty years, but let's round it up. Fine. Twenty years of Texas. I'm fifty-three, and on the cusp of the next number up. The scales tip heavily toward everywhere else. Here before too long, Montana will sink its years deeper into me than Texas ever did. It already has more of my heart, more influence on my creativity, a bigger share of my identity. Still, Texas abides. Still, Texas claims me. Still, I claim Texas. Those holds are coming up through my work first, which means they're coming up in my memories. My latest work is drenched in Texas, even if most of it unfolds farther north. There was no way to imagine Nathan Ray, the central character of the ensemble, without first cozying up to the Texas I knew as a boy, then conjuring a backstory where the Texas he knows is a backdrop of pain and disillusionment and gifts he cannot yet see. It's in the next book—the one with a title in flux, the one that may emerge in 2025, or maybe '26—that Texas takes a star turn, a place both abandoned and returned to. Here's a snippet: Texas was gone, falling behind us a mile a minute, and I was relieved and scared all at the same time. You leave Texas little by little and then all at once, yes, but Texas is also a magnet—a big, southerly magnet pulling at everyone else in the country with myths and manufactured romance and jobs and cheap living and low taxes. You can get away, but can you ever really leave? My answer, beyond the bounds of fiction? It's complicated. You can leave, sure. But you come back. The only thing is, I've never made a return stick. But it's early yet. I'm still upright and breathing. In the foreseeable term, of course, I'm not going anywhere. I live in Montana, I love living in Montana, and the father with whom I couldn't live in 1985 really does need me now. He lives in Montana. As long as he draws breath, and probably longer, here I'll be.

But I can't quit Texas, and unlike the answer I'd have given you twenty years ago, I don't want to. It's in my head and my heart and my memories, and the last of those is the most essential ingredient in doing this thing I do. That, I believe, is why Texas seems so insistent these days, like a song that I can't get out of my ears. It's having its say in my work, and I'm making room for it there. Perhaps, in some future I cannot yet see, I'll make other accommodations for it, too. Occasionally, either not knowing my history or not caring, a friend or acquaintance will say something cutting about the place that shaped my boyhood, and thus my life. And I'll cringe, because the cuts are easy enough to administer when Texas serves up such ridiculous stereotypes, such a bloody history, such casually cruel politics. On a day when I can find patience and indulgence for a friend's carelessness, I will say, OK, yes, but Texas is also a vast and beautiful place, full of beautiful people who contain multitudes. Texas isn't made for anyone's tidy little box. It's destined to spill out from whatever attempts to contain it. In short, it cannot be seen in simplicities when its complexities abound.

0 Comments

8/14/2022 0 Comments Small. Appreciative.

Life has some funny cycles. As I write this, I'm just a handful of hours home from a couple of days in Great Falls, that visit coming on the heels of another Great Falls trip the previous week. Before that, I think the last time I was in Great Falls other than just passing through was ... 2010? 2011? A long time ago. I hope this means I'll be going back sooner rather than later. I like that town.

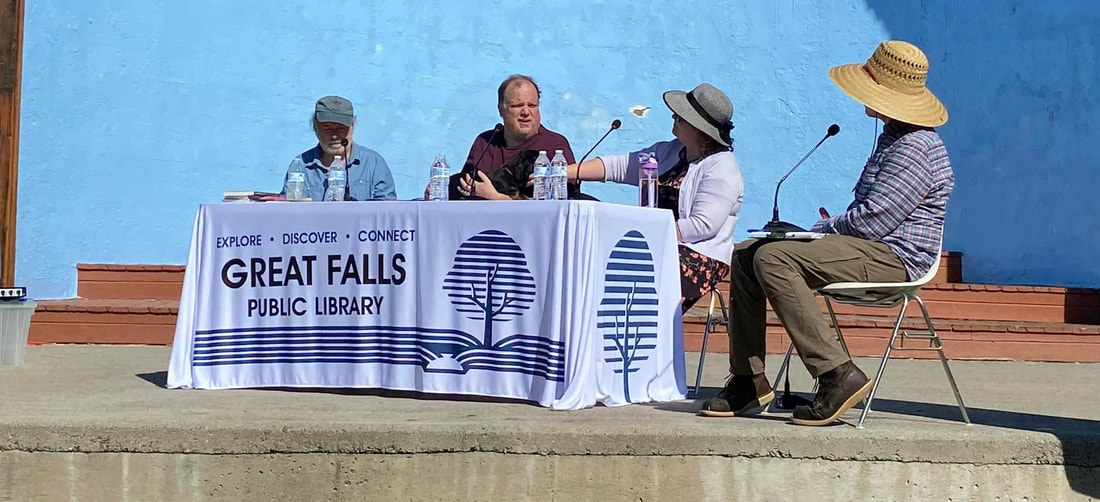

I was there to take part in a panel discussion of Montana authors, sponsored by the Great Falls Public Library as part of the Big River Ruckus festival. It was a blistering-hot morning, and my planet-sized melon sizzled. As is often the case for literary events, we didn't have a big crowd (I believe the applicable adjectives are "small" and "appreciative"), but we had good times in abundance. I joined poet Dave Caserio (a Billings denizen, like me) and writer Kristen Inbody, and we had a rollicking good time talking about writing in the West, ideas, how place figures into our writing, and much more.

Whenever I do an event, I'm put in mind of a line from a Pernice Brothers song: It doesn't matter if the crowd is thin / we sing to six the way we sing to ten ...

It's a funny line, of course, but the sentiment is dead-on. I've seen everything there is to see at readings, book signings, and the like: small gatherings, no gatherings, full houses, whatever. Whatever you get, you deliver as best you can to whoever was kind enough to show up. It's a charming business in that way. Every hand that's there to shake—or the only hand that's there to shake—is another chance to make a connection. And connections are everything. One person showed up? Great! Take that person out for dinner or a drink. The whole town showed up? Fantastic! Now you've got a party.

Love is love, and we love the stage ...

Before heading home Sunday, I drove out northwest of Great Falls to see the dairy farm my father grew up on. It was only the third time I've been there, and the second was just a drive-by, but I remembered the route just fine. I drove down the long driveway to where the house is, but nobody came out, and I wasn't about to go knocking on doors, so I took a quick look, then slipped out of there quietly.

Here's a nice shot from atop the bench, about a mile and a half from the farmhouse. Sorry for the telephone pole bisecting Square Butte.

When I talk about writing and where it comes from, as I did during our discussion Saturday, I'm apt to talk about how we are born with stories. We're not blank slates. Going to a place that was formative for my father (in mostly devastating ways, unfortunately) is a good demonstration of what I mean. It allows me to put eyes on his life, to process it, and to make sense of my own. Because of the way his life was shaped by his early experiences, he had a story to transfer to me, one that I would start to carry when I came into the world, along with the one I would live out in my own days. The same is true, of course, with my mother, and her parents, and his parents, and their parents before them, and on and on. The stories are inside us, already coded. We draw them out, interpret them, weave them with imagination and memory (in the case of fiction), give them purpose. It's a beautiful thing. Even when the underlying material is made up of mostly terrible things.

"Before you climb the mountain, first the foothills must appear."

It was a long, hot, empty drive home for Fretless and me. He mostly slept. I mostly sang along with the random shuffle of iTunes, something I can get away with when I'm alone. (I certainly wouldn't subject any human to my singing voice.)

On the final stretch home, I received a particular delight when iTunes served up one of my favorite songs but also one that doesn't often swim to the top of the heap. I suppose most songs remind us of something, someone or some point in time. Certainly, this one does that for me. There's a tinge of melancholy, though, because it's a reminder of a friendship I miss. It's been many years since it went by the wayside, and I've come to embrace something I was told a long time ago when I was seeing a counselor while in the midst of divorce: Some friendships are like cab rides. They have a beginning and an end. Indeed, they do.

Anyway, it was nice to hear the song at that moment, with my head where it was (reeling in other memories), to recall good times with someone who was a good friend, and to put out a silent wish: I hope the good life has found you where you are.

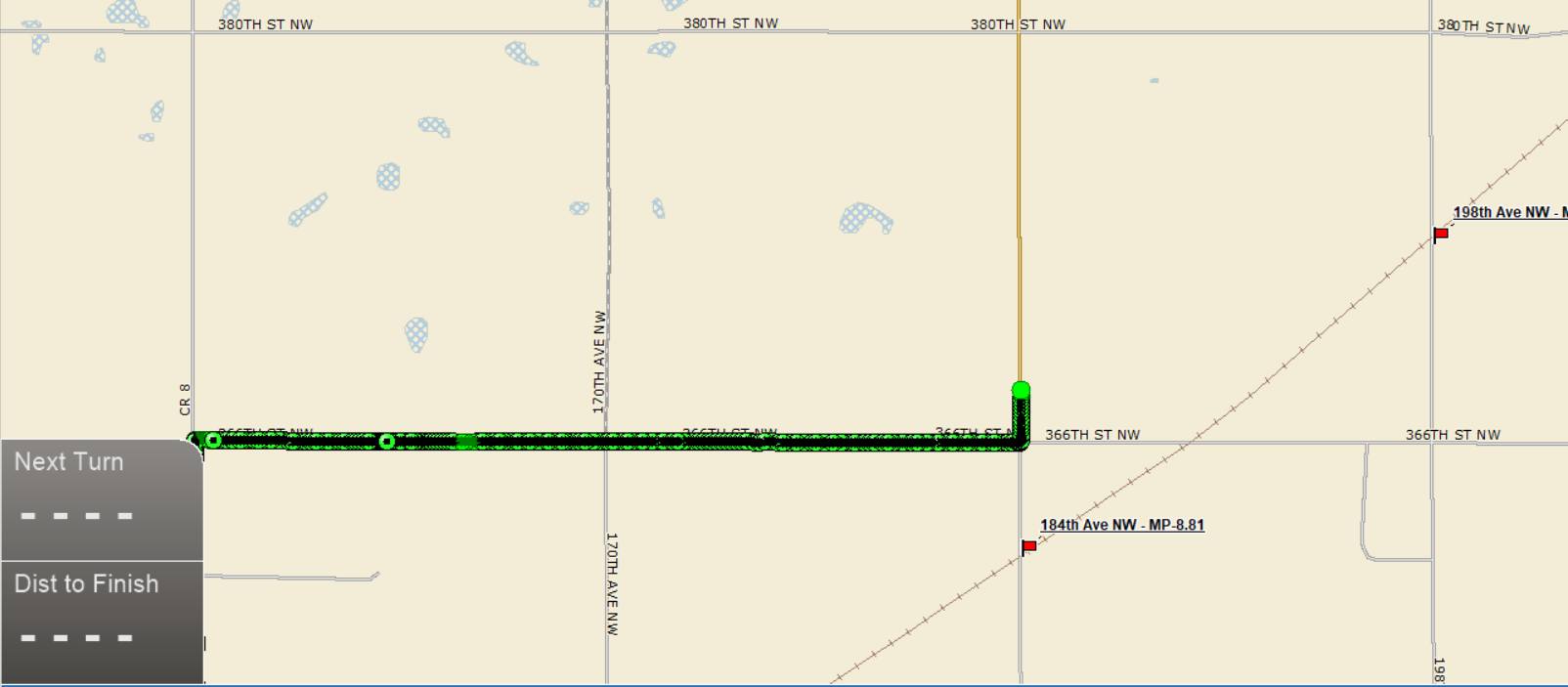

It certainly has found me. Coming home—to Billings, to Elisa, to Spatz the cat—is the best arrival I've ever known. It makes the leaving worthwhile. 6/25/2022 2 Comments The Road Called, and We AnsweredHere we are, nearly halfway through 2022, and I've only just caught up to reconciling something that happened in late 2021. (I suspect this is either because I'm slow on the uptake or because I just hadn't taken the time to lean into my feelings and sort them out. Maybe even both!) At any rate, at the end of the year, the company for which I'd done some occasional pipeline inspection work for the past several years folded up its U.S. operations. Just like that, I was out of a gig. First, the important stuff: It wasn't more than a trickle of an income stream, so it's not like I was jobless or under the threat of imminent financial disaster. It wasn't and never had been a career, so I wasn't grappling with the loss of self. The point being, it wasn't a massive blow to the bottom line or self-identity. And yet ... It was a blow, undeniably. I felt the absence, and I felt a little unmoored by the fact that I didn't have any work trips coming up. I found myself thinking inordinately about the places I would commonly go on these work trips—Buffalo, N.Y., and Chelsea, Mich., and Michigan's Upper Peninsula, and the far reaches of Minnesota and Wisconsin. My thoughts would drift to Minot, N.D., where I'd gone for my first such job, way back in 2015. And then it occurred to me: What I'm really missing here is that liberating sense of being gone. I'm 52 years old, and I've never lost that urge toward motion, travel, getting in the car and going, any direction will do. I like hotels and corner restaurants. I like people watching in places where I don't know anyone. I like seeing what's over the next horizon, even if I've seen it before. By now, I surely most know that it's incurable. So I told my understanding wife that I needed to go, and I packed up the dog and a week's worth of clothes, and I went. The idea was to go to Minot and, from there, launch revisits of a few pipeline routes that emanate from there. The Minot part was easy enough. The rest, though, went against my expectations. Here's a glimpse (material stolen from a subsequent Facebook post):  See the orange post there? I tracked my first pipeline tool from that site (smack in Berthold, N.D.) back in 2015. See the orange post there? I tracked my first pipeline tool from that site (smack in Berthold, N.D.) back in 2015. I haven't missed the pipeline work—which, you know, is work—nearly as much as I've missed the travel and the solitude. The solitude most of all. I don't think happiness exists in a fixed place; it is, instead, what you make of it and where. But if I'm wrong about that and happiness really is out there in a place you can pin on a map, then I'm fairly certain that place is on a tertiary road in some lonely precinct where no one goes on vacation. I came here thinking I'd ride the full length of a few lines, stopping at every checkpoint and taking them in, and I was wrong about that. I don't need that much immersion. I just needed to be out. Away. Gone. Just for a few hours at a time. God, how I loved it. God, how I've missed it. On our last full day in North Dakota, Fretless and I rode a small portion of an 85-mile line that runs northwest from Berthold, N.D., to the Canadian border. It was, simultaneously, a total kick of nostalgia and an entirely new experience. The only time I did this line for real occurred in the deepest of winter, 2017. It was bitterly cold that night. The snow was in drifts. The wind blew the snow around in ways that would mess with your perception of things. On those dirt roads, some of them just two-track, you'd see a pile of snow and you'd stop the car and get out, the wind biting your face, and you'd walk it first to make sure you wouldn't get stuck. You don't want to get stuck, believe me. It's happened to me, more than once. It's bad. I once waited for seven hours in Wisconsin, my work vehicle sunk to its axles in a blizzard, for a tractor to come and yank me out. You don't want this. See the pipeline marker in the photo above. To do my job, I'd have to wade through snow, sometimes chest-deep, and put my sensory equipment there to record the tool passing by, deep underground. Then, after a passage, I'd have to wade back out and get the equipment, then try to swim back to the vehicle, hoping I didn't get hung up alone out there. Meanwhile, the tool was zipping along to the next checkpoint at about 7 mph, which is really hauling ass. It was desolately lonely and dark and cold and scary. I loved it so much. The line parallels railroad tracks (see the map above), which cross the road at uncontrolled intersections. In the night and the cold and the dark, snow flying sideways and obscuring your vision, you'd have to be careful, hanging out in those places. When Fretless and I went out, though, it was different. Warm and clear. Sunny. No snow. No drifts. More red-winged blackbirds than I could count, although not one of them stood still long enough for me to get a picture. Farmland was verdant with moisture, not gray and white and foreboding like in my memories. That night I ran the line for real, in March 2017, we finished at the border and the snow was coming down in massive clumps. I drove to my waiting hotel in Williston, more than 100 miles away, unable to see a damn thing, holding my phone in front of me and using the GPS program to keep my truck on the road, or where the road was supposed to be. I didn't tell my wife about that until a day later, when I was safely home. I don't miss that kind of stuff. A little more than a week ago, when I'd had enough, I asked Fretless, in the backseat, if he wanted to go back to the hotel. He wagged his tail agreeably. I cracked the windows, letting in some fresh air, and we got the hell out of there. It was glorious. Every little bit of it. I had to work the evening of getaway day, and long gone are the days when I can drive for eight hours and work for another eight, so we stayed that night in Sidney, Montana, another dot on the map rich with memories. Again, borrowing from Facebook:  See the windbreak there? That's on the southern edge of Fairview, Montana, a little town that straddles the Montana-North Dakota line. In late summer 1981, when my dad was in the midst of moving his drilling rig from one town to another, the right-front tire on his International Harvester Paystar 5000 blew out and he, with much effort, brought it to a stop right there. I have a clear memory of this because I was in the passenger seat, so it was my side of the truck that dipped precipitously, as if we were going to pitch over on our side. I also well remember it because it was a classic bad news-good news scenario. Bad for obvious reasons, and for these reasons: Dad's hired hands, who'd ordinarily be following him, had gone out ahead of us by a couple of hours. We were alone. Good because there's a house right there, and a small town just ahead. Easy to make a call, even in 1981, and get some help dispatched. Now, lemme ask you this: What do you suppose the percentage chance was that this boy, who lived at the time in Texas, 26 years later would marry a woman from tiny Fairview (population now 900, but much smaller then)? As it turned out, 100 percent. (We divorced seven years later, so it's less a fairy tale than an interesting coincidence. But still.) OK, let's move a dozen miles down the road to Sidney. That train engine, in Veterans Memorial Park, with Fretless offered for scale? I climbed all over that thing that summer. I was 11 years old, and that's pretty much the recreation that was available to me. The city fathers hadn't yet fenced it off, so I was free to clamber wherever I could get to. I also chewed illicit tobacco, given to me by my dad's helpers, who encouraged me to have all I wanted, knowing full well what would happen to me. Bastards. Anyway. Across the street, still standing but no longer operational, it seems, was the Park Place Motel. I lived that summer in one of the bottom-floor rooms, with dad and his wife. It was entirely too cozy, entirely too stifling, entirely too familiar. And yet, I'm thankful for the memories, which quite without my realizing it were becoming fodder and fuel. I've set stories in that park, and in those fields beyond it. With very little disguise (or even much of a name change), I've turned Fairview into a character all its own, the little town of Grandview in This Is What I Want.

It's all been a gift, every bit of it. I'm grateful, all the time. And I can't wait for the next trip ... 6/18/2022 0 Comments Scenes from a GetawayWords from the getaway—four days in North Dakota and the edge of Montana—to follow ... soonish. For now, enjoy the pictures!

9/24/2021 5 Comments Back to the Fork in the RoadIt's Sunday, September 19, and I'm on Interstate 25 in Casper, the nose of my car pointed north, toward home, a few hours away. I'm tired. My dog, Fretless, lies languidly in the passenger seat. He's had enough after a week away. So have I. Home, my wife, the cat—they all await. We have plenty of gas, had a bite to eat back in Douglas, fifty miles behind us. We have everything we need. The smart play is to get beyond this oil town and open up the cruise control a bit, see what this Toyota can do as we zip back into the emptiness of Wyoming and, eventually, get pulled into the embrace of Montana. So, of course, I exit the interstate, pick my way through downtown Casper, find CY Avenue—I once called it, in a novel, "the spine of the Casper grid system," which may or may not be true—and follow its familiar path to where I turn off for Mills, a little town north of Casper, and as I do, the well-trod memories come at me again. What I've come to see has been seen before, many times, and is likely to be seen many times yet, and if this particular side trip is taken as evidence that my life is in reruns, I will say only this in disputing that notion: Context is important, in all things and especially in this: I find it instructive, or at least perspective-granting, to be reminded of the life I might have had so I can better appreciate the one I'm swimming through. It's Friday, September 24, the day I'm writing this, and I'm reflecting on a spontaneous turn in a phone conversation with my mother this morning as we talked about other things. We talked, quite organically, about a decision she made for both of us in 1973, my third year. I was a capable kid, even at that age, blessed with an ability to carry on conversations with adults, but this matter was beyond my perception. She didn't want to live in Mills, Wyoming, anymore. That was surely half of it. The other half was that she didn't want me to live in Mills, Wyoming, anymore. She looked at the present, our life with my father there and what it seemingly held for us, and she projected out her future and mine and didn't like where those lives seemed likely to end up, and she did something about it. She took us out of there, into life with a man she'd met that year, the brother of her best friend, a man who lived in Euless, Texas. Not that it's anyone's business, but they hadn't had an affair. They'd had a connection, a chance meeting at a party that turned into a deep conversation that blossomed into a friendship and has become a nearly 48-year marriage. We talked about it this morning, Mom and I, this decision that with each passing year strikes me as more and more brave, more and more essential to both of us (and now to so many others—generations of others), more and more the line of demarcation, in strictly selfish terms for me, between where my life was pointed and where it ended up. I can see now, when I'm more than two decades older than she was then, how much gumption it required for her to do what she did. She was alone there, much of the time. She was 28 years old, and while Dad might not have represented maturity or loving or grace (I love the man, but let's be honest about the limitations), our prospects there were much more certain than they were anywhere else. There was a home well on its way to being paid off, an ascendant business, money in the bank. It would have been all too easy to stay. Many people have stayed for less. Mom saw the future and she left. I'll never receive a finer gift. So, you see, Mills, Wyoming, is actually a bit player in this what-might-have-been contemplation. It wasn't Mills we were escaping so much as who was there and what our life was there. It could have happened in Moline or Schenectady or Topeka. Could have, but didn't. This is, at its heart, a human story, a story of a boy with three parents who've imprinted him in wildly varying ways. I love my father, a love that shines through my struggles to understand him and his to understand me. It's a love strong enough to withstand my suspicion that my start in life would have been less than it was had I finished my growing-up years in his house. The math of that situation is inconceivable to me, given the way it all went. It would have been Mom and me in some kind of alignment agaInst the gravity of the way he is, the work that was always taking him away from us, and the instability of the home we were living in. I'm certain Mom's decision all those years ago hurt him. I'm also certain, if Dad can access clarity and honesty, that he'd say it needed to happen. For all of us. And what can a boy like me say about his mother that hasn't been said in better ways by better thinkers? She is pure love when it comes to her children and her children's children, but to leave it at that misses the fullness of who she is. At an age that seems to me, now, to be impossibly young, she was relentlessly wise. She had aspirations for herself (and has them still). To my ongoing gratitude, she could see a time coming when her son would have them, too. In so doing, she brought me into the sphere of the man who became my stepfather. Back then, he was a 31-year-old sportswriter at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, a man who had his own broken first marriage, a son, and regrets. He also had a shared hope with Mom that they could make a go of it together. I can scarcely remember a time before his presence in my life, and he has never, not once, treated me as anything but his own. That has made all the difference. I go back to Mills to remind myself that it could all have gone another way. Could have, but didn't. So what do I make of Mills, all these years later?

I think it would be presumptuous of me to make anything of it beyond my sliver of experience there. It's steeped in nostalgia and memories and wonder. Its presence on the outskirts of my life has been a professional gift, surely (the old memory + imagination thing), as well as fodder for the occasional facile joke. (One could certainly quip about "welcome to Mills, please set your watch back 20 years" or wax irreverent about how hard the wind blows there.) The thing is, I've lived enough places and known enough people to realize something important: Most anyplace can be home, depending on who's doing the inhabiting and what they bring to it. I suspect—but don't know for certain—that my life would have harder and less interesting had I grown up in Mills. It's the not knowing, of course, that makes it such a delicious ponderable. So I go back, and I look around, and I try to imagine who that boy might have been, what kind of man he might have become, where he might have gone and what he might have seen. And because Mom imagined something else entirely, way back in 1973, I can be ever grateful for the real story that lies alongside the conjecture. 6/10/2021 0 Comments The Pig Life, in the DarkOriginally published January 21, 2021

A preamble, then we’ll amble: I’ve had what I consider to be four careers, and they’ve lain together haphazardly, overlapping in some ways and standing free in others. I was a newspaperman before I was a novelist, then I was both of those things together, then I ditched the newspaper life while I kept writing and started freelancing, then I became a particular kind of pipeline worker (1) while writing and freelancing, then I returned to journalism, this time on the digital side, while I kept writing and freelancing and occasionally pipelining. I point all of this out not to build a résumé—there’s been quite enough of that, thank you—but instead to get at something I’ve realized about myself only in the past few years: I’m happier when I’m busy on several fronts. I’m less likely to be thrown by life’s intrusions, I feel more a part of the existence I’ve been granted, my energy level stays up, my mind remains limber. It’s good to know yourself and your peculiarities. Beats the alternative, anyway. When I left print journalism in 2013, it was entirely a function of opportunity and sloth. I was making more money writing fiction than I was building newspapers on the swing shift, and I had to work a lot more doggedly in the office for that lesser recompense. I granted myself a release and the gift of laziness. But here’s the thing: After twenty-five years’ worth of having somewhere to be five nights a week, I quickly grew bored with all of my wonderful freedom. That’s when I became a pipeliner. And that’s where we’re going today: into the finer details of a job that gets done while its doer hides in plain sight. As the pipeline flows, it’s a shade over 330 miles from a certain launch station in east-central Missouri to a certain receive valve in northeastern Oklahoma (2). That’s line flow. If you’re a pig tracker—and I was, and I am—you’re confined to surface roads, so the distance is considerably longer. My first multi-day tracking job, back in 2015, covered this distance at the robust rate of three miles per hour. You can do the math, right? That’s 110 hours from the time the pig—the pipeline tool—is put into the system and sent downstream until it is received on the other end. Further math brings that 110 hours to four and a half days. After a pig is launched, there must be twenty-four-hour coverage of its underground movements until it arrives at the receive valve. This is where the pig tracker comes in. This person drives to pre-determined places where the pipeline crosses the surface roads and, using an array of sensory tools, takes the measure of the pig’s progress—how fast it’s traveling, how long it took to cover the distance from the previous checkpoint to the current one, when it should arrive at the next crossing, and so on. On the crew I was on, we worked in two shifts, day (noon to midnight) and night (midnight to noon). I worked nights that week. The experience struck me as an inversion of reality, casting me almost into a dreamlike state for the entirety of the week, rather like the one Alaska visitors sometimes experience when they travel there during the summer solstice (3). If not for an intricate series of alarms on my smartphone, I would have lost all sense of time (4). More than once, I lost touch with the day I was in, snoozing (or trying to) in the daylight hours and being active while the world around me slept. I explored frontiers of exhaustion I’ve not yet revisited, even as I’ve done dozens of jobs since. I also tumbled irretrievably into love not just with the work—which isn’t terribly strenuous and is done easily enough if you can run a basic suite of software—but also with the intrinsic perks of it. My friend and best man Jim Thomsen found his way into both fiction writing and freelancing at about the same time I did and, like me, made the transition after a long career in print journalism. We’ve had a lot to bond over during these years of our friendship, and of the many things he’s said that I agree with, this one stands out for its perspicacity: Writers have overdeveloped interior lives. Guilty. And let me tell you, pig tracking is an orgy of indulgence for someone who lives largely within the confines of his own thoughts. First, there’s the silent solitude. It doesn’t begin and end. It begins, it endures, then it’s interrupted by a passage of the pig, then it’s engaged again, then it endures some more, then it’s interrupted again. And so on. On my first full night of this particular job, my partner and I had thirty passes, covering our twelve hours on shift, as we went leapfrogging down the line. That’s a lot of sitting around and waiting for the pig to pass by. That’s a whole lot of exploring your own notions about a whole lot of things. Second, there’s the way the hours flow one into the next. “Night shift” is a bit of a misnomer, because by the time you join the line at midnight, night is already well along and cruising hard toward daybreak. When you’re alert—senses attenuated, your eyes adjusted to the darkness, your skin a prickle—at a time when most everything else slumbers, you notice a lot of things you might otherwise miss. How much noise you make just walking around in the dark (5). The rhythm of your own breathing. The spin of the earth, as the moon moves around you and then cedes to the sun. The migrations of nocturnal animals. The fullness of the sunrise, both the actual unveiling and those final minutes of darkness that trickle into it. How the hours beyond the dawn feel a little like they did after senior prom, when you’d stayed up for hours and emerged fuzzy-headed into the light. The only difference is that you’re wearing a yellow safety vest instead of a cummerbund. I found a lot of latitude to go deep on the things that sat in my head. That time alone was a great gift, an opportunity to noodle out some story I was working on, to reconsider some past encounter, to perhaps even reach out in the wee hours and offer amends to someone with whom I was at loggerheads. My wife, then my girlfriend, and I were a year out from our wedding when that job occurred, living across the country from each other and working steadily toward merging our lives. I had a lot of time to envision the shape of the days that were coming our way. Some people go deep into the backcountry to do their thinking. I’ve managed to find my solitude along fencelines in Missouri and Kansas and Oklahoma (6). The worst part is the first couple of hours after a night shift ends. The principle of reporting to or disengaging from that kind of work goes something like this: Save the long drives for the daytime. So if your shift ends at noon, you have to calculate where the pig is going to be twelve hours on and go find a hotel room close to that spot, so you can quickly get back to it. It’s both art and science, anticipation merged with the variables of time, speed, and distance. On that job, I slept in Marshall, Missouri, and Harrisonville, Missouri, and Iola, Kansas, and Bartlesville, Oklahoma. Every one of them was a long drive, fifty-plus miles, from where my shift ended. The sun is up, the day is in full, and you’re driving into it while trying to fight off exhaustion. You get headachy. You get to your hotel and maybe they’re not ready for you, because, you know, check-in is at 3 p.m., and that’s far too late—by then, you’ll want to be deep into the REMs. So you beg and you plead, and if you’re lucky, they’ll finally give you a room. You shower, then you eat wherever you can, because you really ought to eat something, and you do not want to turn on that TV, believe me, because you’ll never get all the way down into the best sleep if you do that. And sometimes you flip it on anyway and the news of the day gets the attention you should be giving to your pillow. The most tired I’ve ever been, in the confines of a single day, happened about fifteen years ago, on a trip with my first wife before she became my first wife. We drove from Billings to Yellowstone National Park and all through it, then came on home. Fourteen hours, and I did all the driving, except the last thirty miles, when I told her, in all seriousness, that I could see dinosaurs running alongside the road. She rightly asked me to pull over so she could take the wheel. I never saw dinosaurs on a pigging job, nor did I ever see bedsprings in the trees (7). The weariness swallows you in a different way out there. After the Yellowstone trip, I slept for one night and was subsequently fine. During a five-day pigging trip while on the night shift (8), your compromised sleep rolls over from one day to the next, and each round, you’re just a little more punchy. It’s a weird duality, though, because the sluggishness exists outside the job—I didn’t have the bandwidth for answering personal emails or undertaking complicated phone conversations, but in the narrow scope of tracking the pig, keeping the records, staying on top of where it was and where it would be, I felt ever sharp. It’s a strange thing to live in immediate clarity but to feel the mushiness and see the slow-motion unfolding of everything else just beyond your frame of vision. And here’s a kick: I love the night shift. I vastly prefer it to the more normal cycle of the day shift. The dreamlike state beckons me, I think, because I come by it honestly. Away from the pipeline, I’d have to indulge in alcohol or some other powerful drug to feel the same sensation, and I’m not indulgent in those ways. Time and motion and the absence of light achieve the same state at a much lesser cost. A new novel came out this year, my first solo effort since 2017. It’s titled And It Will Be a Beautiful Life, and at its center is a man named Max Wendt. He’s a pig tracker. It was probably inevitable that this sliver of my working life, something I initially undertook to fend off boredom, would find its way into fiction, but you’ll just have to trust me that I didn’t become a pig tracker so I could write about a pig tracker (9). The great Larry Watson, interviewed in Montana Quarterly several issues back, said something that sent me into a fit of fervent nodding. “I write from memory, not observation,” he said. “Yet my memories are formed by observations, and then memory and imagination distort those observations into something useful for fiction and something that’s also truthful in its own way.” Mr. Watson’s words are an eloquent cousin of a cruder equation I’ve often sketched out: memory + experience + imagination = fiction. The memories and experiences (and distorted observations, as Mr. Watson points out) of being a pig tracker inform the character of Max Wendt. But my life on the pipeline is not his. More important, his life off the pipeline is not mine. One of the great and worthwhile struggles of this existence is figuring out how to balance who we are and what we do and finding a way to stow the overlap. It’s hard to be good at what you do if it’s not also, at least to some extent, what you are. And yet, it’s so easy to lose yourself inside what you do to the point that you lose touch with who you are. That, I think, is the central struggle of Max Wendt. He’s a pig tracker. It’s what he does and how he sees himself, and much to his consternation, it turns out to be not nearly enough. I am not him, and he is not me, but I get it, man. I do. Endnotes (1) — Pig tracker. It doesn’t dazzle on a business card, which is OK, because not many pig trackers have business cards. (2) — I don’t talk about the companies for which I do work, for obvious reasons. I will say, though, that the job of a pig tracker exists on the safety end of things, and even if you’re anti-pipeline, you ought to be glad someone is doing that work. The pipelines are out there. Do a Google image search for “U.S. pipeline map” and behold the tangle. (3) — People mow their lawns at midnight. It’s wild. (4) — The alarms are to ensure ongoing communication with the pipeline control system. You lose track of time out there. An alarm reminds you to call in and let the engineers know where you are. (5) — And yet, there’s no fear. At least, I’ve never experienced it. I’ve been careful not to wake up folks in nearby farmhouses, and I’ve certainly been startled (a dog running loose, raccoon hunters tramping out of the woods, even a bear crashing through the brush), but I am not afraid of walking into the dark. (6) — And Michigan and Ohio and New York and Illinois and Indiana and Minnesota and Wisconsin and North Dakota. I’ve been everywhere, man. (7) — A musher I knew in Alaska, Tim Osmar, talked about seeing mattresses in the trees toward the end of the Iditarod one year. He needed some sleep. (8) — The day shift, on the other hand, is a cinch. Easy to bag eight hours of sleep. Easy to take your breakfast at the usual time. Boring, if you ask me. (9) — Who else are you going to believe? I’m the only one who knows. Originally published January 12, 2021

In September 2019, my wife and I came to a decision we had been nearing at different speeds and while balancing factors that both aligned and diverged: We would put our house in Boothbay, Maine, up for sale and return to Billings, Montana, the city we had left in late May 2018. We’d had a short, but sufficient, tenure in Maine and found it wanting in terms of our day-to-day life. Or, perhaps, we were the lacking ones and simply didn’t have what it takes to live there contentedly. Whatever the case, after several months of disharmony prompted by a move that just hadn’t worked out, we stood on common ground: We would end the Maine portion of our life together and haul ourselves and our pets and our stuff (and my father and his dog) back to Montana. Let me cut to the chase here: It has been a good decision, the proper one. We are relieved to be back in the house in Montana that we couldn’t sell in the first half of 2018 (a house that now would be plucked up almost instantaneously for a price that would subsequently lock us out of the market; time is weird, and so are the unforeseen consequences of a pandemic). With so much in flux and uncertain—the arc of the coronavirus, when we might see loved ones again, the republic itself—we check in with each other from time to time: Is everything still good? Are we still OK with this decision we’ve made? The answers are yes, right down the line. Nonetheless, my thoughts often do wind back fifteen months to that decision, and to the subsequent six-month interregnum between the listing and what eventually followed: the purchase contract and the closing and the loadout. I ponder how freeing it was to simply commit to a course of action, how calm we were after the decision was made, how we never got over-eager or frustrated as we waited for a buyer to fall in love with our little Cape house. And how, in a quite unlikely and unexpected way, I made my peace with Maine on the long fadeout. This is about that last part, in particular. I wrote about this for the Boothbay Register while we were still in Maine, so here’s the TL;DR version: The adoption of our miniature dachshund, Fretless, was followed shortly by my doctor’s admonition that I was approaching fifty and needed to exercise a good bit more than I had been. His final words on the subject: “Make Maine your playground. Take that dog with you.” Never let it be said that I can’t obey orders. The Boothbay Region Land Trust is the steward for twenty-six preserves on the peninsula, and while Fretless and I didn’t get to all of them, we made frequent use of the ones nearest us. I fell deeply in love with this particular aspect of Maine, and while it alone was not enough to offset all of the factors compelling me (and us) back to Montana, the love was and is real and deep and true. Those coastal rivers are breathtaking. I was enchanted by how easily I could walk away from my car at a trailhead and disappear into a stillness and a silence that were not at all intimidating. I could hear my breath and my heartbeat and Fretless’ little steps in the woods. It hard-bonded us, making him my faithful companion and me his trusted doggie dad. At the outset of our relationship, we needed what those walks together gave us. It’s different now, here in our part of Montana. The most easily accessible trail in our neighborhood is a concrete suburban path we can walk out our door and join. Or I can pitch Fretless into the car and take a short drive to Lake Elmo State Park, where there’s a manmade reservoir featuring a perfectly adequate, perfectly flat trail looping around the water. The prescribed exercise is good, and Fretless has no complaints, but that slip into the silence of my own head doesn’t really happen here. There’s more sky than scenery, an inversion of the Maine experience, and we’re never far away from the sight of houses and the sound of cars and the scents of an encroaching small city. It’s not lesser, necessarily. Just … different. And when our walk is through, we return to the car and to our house and to the contentedness we’ve found here after nearly two years away. That part, certainly, is a considerable improvement. So what’s the difference here? Why was one place home and the other wasn’t, and why did we have to leave to find this out? As much as I wish I could, I don’t think I could tabulate it on a worksheet. So much of what works or doesn’t work in our lives—I’m talking jobs, relationships, what we do, where we go, where we live—comes down to timing and current circumstance. Once we learn to account for the variable of timing, it’s easier to let go of the things that don’t happen the way they might if we had full control—or any control—over the essential details. It also neutralizes the hard sells of commerce and the trafficking of romantic tropes. You learn to appreciate circumstantial convergences. You also learn to discount the notion of magic when timing can adequately carry the explanation. We moved to Maine and wanted to make it home. We had loved it from afar, and we had spent time there before the move, and we thought we and it would be a match. We were not. There were outside factors that augured against our really settling in. We’d had some income loss that was harder to replace there. My father, with whom I have a loving but often fraught relationship, came with us and moved into a basement apartment in the house we bought, and his presence in such proximity to us had a negative effect on the life we tried to live independent of him. We moved to a county that trended quite a bit older than we are, full of nice people who were insular and embedded into their own patterns. Maine was easy to move to and hard to become a part of, in our experience, but that, too, is a matter of timing. Does the picture come out differently if it had been just the two of us and we’d picked a house in Portland, where there are more people and more outlets for our interests? Perhaps. I don’t know. That time has passed. Or maybe it’s coming around and we just can’t see it yet. Or perhaps we’ll someday find a place we call home somewhere else. Long Island, where Elisa grew up. Texas, where I grew up. Virginia. North Carolina. North Dakota (that would be a surprise, but hey, whatever). Or perhaps, having taken our opportunity to return to Montana, we’re in the place where we’ll stay until we return to stardust. I would be more than OK with that. Time will tell. One way or another. A few weeks ago, as Fretless and I completed our lap around Lake Elmo, we approached a massive flock of Canada geese lazing on the shore. Fretless, the world’s most ironically named dog, one frightened of a melting pile of snow, strained just a little at the end of the leash, curious about these creatures he was encountering for the first time. He wasn’t threatening, yet the geese seemed to have a line, and we crossed it. They took briefly to the air in a mighty thumping of wings. They settled a few yards out in the water and scolded us for the intrusion. It wasn’t quite the majesty Fretless and I often enjoyed in the last place we lived. But it would be unseemly to be anything less than grateful for our chance to go there and take in a sliver of a much more complete picture. I made our apologies to the ruffled geese, and we walked the short distance to the car, and we loaded up. Five minutes later, we were home. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed