|

7/13/2024 0 Comments The Vicissitudes of Life**--I used this phrase in my most recent newsletter, and one of my dearest friends wrote me a wonderful email with it as the subject line. Consider this a case of virtuous recycling. It has been nearly two months since I put something new up here. Sorry/not sorry, as the saying goes. So much has happened, and I have so little to say about it, and that's a strange combination. Confronted by this dynamic in the past, I've found it best to turtle up and wait until something worthwhile comes to mind. If you're seeking mindless blather, surely there's a high-frequency, low-content Substack site out there for you. And yet, enough has changed, and enough good intentions have been met with poor follow-through, that an accounting is in order. Let's do this scattershot style: I've moved. But that's not all. Elisa covered this beautifully in her own newsletter, so I'll neither say a lot more nor take issue with any of it. She now lives in New England, her other heart earth, and I still live in Montana, mine. I'm renting space in a lovely old rambling house in my favorite Billings neighborhood, pushing on with life and art. I have a beautiful office setup that is a joy to pile into each morning. My primary work, which I find interesting and fulfilling, continues apace (you can read a piece I wrote for PaymentsJournal here). Fretless and I take walks, sometimes alone, sometimes with my roommate and her dog. I tend to my dad. I have lunch with friends. It's a good life but also a different life, and I think Elisa would say the same thing. Fiction: At a standstill Once I decided to spring Northward Dreams loose from its intended publisher, spring became a blur as I pushed out a retitled, re-jacketed version of the book and embarked on an ambitious series of appearances. Those have largely subsided as summer has come on, and it will probably be fall before I rev up again. The paperback comes out in November, and that's a good opportunity to hit the road again. I had so much fun with the hardcover. What hasn't been fun—and I'm only being honest here—is going through the wringer of publishing, which can be a heartbreaking business. Writing is the best kind of joy—challenging, yes, but also a test of self, of the quality of ideas, of endurance. Publishing...Well, if I can't say something nice, and I can't, best not to say anything at all. It's not like my travails register as important in the larger scheme of things; hell, they're not even all that interesting to me given all the ways the world is on fire (literally). But if I'm going to write stories—and I am—I will have to resolve my attitude one way or another. Right now, I feel three impulses: 1. Forget publishing altogether. 2. Find another partner like the one I just dispatched, something I never wanted to do, and approach the altar again. 3. Do with every subsequent book exactly what I did with this one. Until my heart settles, I'll do nothing. Playwriting: Stay tuned After the final curtain closed on Straight On To Stardust last fall, I set about writing a new play and turned it around quickly. It's called The Garish Sun--know your Shakespeare—and I hope to have some interesting news to pass along soon. #deliberatetease At this juncture, I'm much more interested in and satisfied by working as a dramatist than I am in writing another novel. These feelings, of course, are subject to change (and always do), so I wouldn't read anything into that declaration. Just something I wouldn't have predicted, say, three years ago. Life, man. Let's have a conversation At the beginning of July, I joined at the speaker roster at Humanities Montana. I'm thrilled about this, as a longtime admirer of and sometimes participant with this organization that advances the humanities in Montana's public life. My program, titled Where Memory and Imagination Meet, draws on subjects that have long held fascination for me—the roles of memory as an ignition point and imagination as the building blocks of fiction—but expands the idea to take in such diverse topics as family, background, community, even citizenship. When we talk about our memories of the things that shaped us and marry those with imagining different ways of talking and connecting, great things can happen. My program, like all the others sponsored by Humanities Montana, is available to schools, libraries, civic groups, and other such gatherings. Information at the link above. If you have a group in Montana that would benefit from this conversation, let's talk! Yeah, but what about all the other stuff? Oh, you mean Craig Reads the Classics? The Saturday craft talks? General keeping in touch?

What can I say? I've been quiet lately. But I'll be back. That's a promise.

0 Comments

5/21/2024 0 Comments Texas. Redux.

I wrote about my home* state several weeks ago. It was a wide-angle, pulled-back view, and I thought I'd unloaded what was in my heart and my head. But here I go again...

No, really, here I go. It's a quick trip this time, not my usual two-day drive down, weeklong stay, and two-day drive back. I'm going for a reading and signing at a bookstore in Keller, the once-sleepy town just north of where I grew up. Like other parts of the North Texas I once knew, it doesn't really match up with my memories anymore. It's bigger, more congested, more diverse, more interesting.

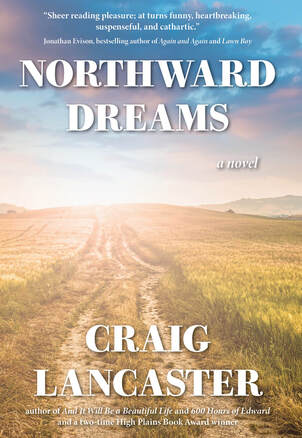

The book I'm taking with me, Northward Dreams, is the most personal piece of fiction I've ever written. The best thing I've ever written, too, not that anyone should trust me to judge such a thing. I'm proud of it. I'm proud of how I willed it into existence. And I really, really want to share it with the people who underpin it, in ways subtle and overt. They're in the book, all of them, whether they would recognize themselves or not. They're in it because they're in me, in the memories I carry around.

To that end, I sent out about 100 postcards earlier this year, addressed to people from across the years I spent in Texas: classmates, old neighbors, former bosses, teachers, colleagues, friends, former lovers. I asked them to come out and see me and to meet this book, to renew acquaintances or to prolong friendships that never ran dry. I'm hoping to see a constellation of faces I recognize come Saturday, but I've also put this event squarely in a holiday weekend, so who knows? I haven't always done a wonderful job of staying in touch as I've wandered the country, looking for the place I'd call home. I found it, years ago. But I've also come to realize that the place I'm from—as much as I'm from anywhere—is also home and always will be.

When I say Northward Dreams is my most personal book, I'm thinking, among other things, about this snippet from one of the four timelines the novel covers. Here, in 1972, Electra and her little boy have arrived at their new home in Texas:

After they’ve gone downstairs, after Electra has made her assessment of the pantry, after she’s pictured the days stretched out before them, after Nathan, red-faced and watery-eyed, has come down and asked for a glass of water, after Charley has fetched the rest of their things and stacked them by the door for sorting out later, after they’ve come back up the stairs, quieter, the three of them lie askew on the king bed. Charley is on his side, head propped up by an angular arm. Electra lies far opposite of him, attentive to her son, and Nathan sleeps in between, curled like a kitten’s paw and under a loose blanket. Electra reaches across the distance, and Charley takes her hand. “Probably not what you expected.” “It’s everything I expected,” he whispers. “You?” “It’s what I want,” she says. “Me, too.” “He’s really a good boy,” she says. “I know.” “It’s a lot to deal with.” “It is.” Charley sits himself up, careful not to jostle the boy. “Kids are resilient, though. I ever tell you about when we moved from Vernon to Wichita Falls?” “No. I’d remember.” “You went through both towns,” he says. “I know.” “I wish I could have been there.” “I know,” she says. “Fifty-some miles, might as well have been moving from earth to the moon. I was nine. Everything I knew, every friend I had, they were all in Vernon, but my dad, he was a history teacher, and the high school in Wichita Falls, they offered him $15 more a week, so we moved. I didn’t have any say.” “Had to be hard at that age.” She’s thinking now of Nathan’s best friends, the Miles boy two doors down and the Fletcher kid, the one she doesn’t much like but whom Nathan adores, and how she plucked him up and took him away without his getting to say goodbye. She hurts for him in a way that she hasn’t allowed herself to think about until now. “Hard at any age,” Charley says. “But the thing is, in the end, I made new friends. Wichita Falls became home, every bit as much as Vernon had been. I adjusted. He’ll adjust, too.” “Tomorrow,” she says, more thoughts she’s held at bay rushing toward her now. Enrolling Nathan in school. Finding a job. Learning where the supermarket is. “It’ll all get done,” he says, as if inside her head. It’s a talent he has. She leans across and kisses him for the first time. Where all of that comes from is both imagination and memory, little snippets that I heard, others I conjured, all of it front and center in my brain, ready to be accessed when I got hold of a story that needed it. This story. This place. Another time of life, forever salient because the decisions that were made had such gravity to them that their effects radiated out to lives yet to be launched. It's powerful stuff, fiction. Often more powerful than the real life that informs it. Now we come to a man in Northward Dreams who's misunderstood, misjudged, and taken too lightly. He's also a ghost and a whisper in time. He's the father sixteen-year-old Ronnie, in the 1952 timeline, reaches faithfully toward. He ends up being the car bumper in the dog's teeth. You've got him. What are you going to do now? When Oscar's timeline-breaking chapter comes in, roughly halfway through the book, it's the dawn of the 1970s, and he's far afield of where we discover him in the main narrative, working his handyman schemes. In an episode of Rich Ehisen's Open Mic podcast, I described Oscar as walking unwittingly into the teeth of his own demise. An excerpt: That's the thing about rooking people out of what's dear to them. It doesn't always work—and when it goes wrong, it's sometimes spectacularly so—but the cops almost never get called. The shame of it all is too great. How could they be so stupid, so naive? It's what you count on—that they are, in fact, so stupid, and that when the deed goes down, one way or another, their primary concern is making sure nobody else finds out. Isn't it pretty to think so, Oscar, you fated man? Read on... (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) PreviouslySo I hear what you're saying: "Craig," you're saying, "just how much of this thing is memory and just how much is imagination? You're hinting at both, but you're not really giving me the scoop. Is Northward Dreams mostly memory or mostly imagination?" Yes. That's my answer. OK, OK, so as we dive deeper into the characters and their breakout chapters, here's where the imagination definitively comes in. Erica Stidham--Charley's eventual wife, Ronnie's former wife, Nathan/Nate's forever mom, a woman with her own power dependent on no man—is no longer with us. The woman whose life provided some inspiration for her—remember the great gift I talked about in the previous installment—is most assuredly still here. She's my mother. I ought to know. You happy now? A minor bit of craft talk: When I start writing something new, I usually know little about what is going to happen but much about who will be in the middle of it. That was mostly true for Northward Dreams, save for one character: Electra. I always knew she'd be leaving early, mostly because I deeply knew the pain her son was in, and would have to be in, and would spend the story fighting against. And sure enough, when the structure of the story began taking shape, we eventually got to Electra, and her busting loose from the established timelines had to happen in a way that fortified the loss of a little boy who grew to be a good, flawed, troubled man: It's one of the cruel jokes of the universe, that he'd come to you not a year and a half ago and said, Am I going to die someday? ... You'd had to sit him down for one of the Big Talks that's in all the child development books, and you'd had to explain that, yes, he will die someday, we all die after all, but not for a long, long time. Are you and Charley going to die? Yes, but not for a long, long time. Daddy? Yes. But again... More craft talk: I mention empathy a lot. It's an essential ingredient. When a memory prompts an idea, imagination sweeps in and leaves you with characters whose defining characteristics and subtleties are yet to be discovered. Empathy—understanding them and their thoughts, choices, and motivations—is the pathway to realizing what you wish to do with the work. I found empathy with Electra, and found her to have surface-level commonalities with my mother but also to possess qualities that were uniquely hers. I didn't have to imagine my mother's death—and good, because I would have hated to contemplate that. I had to feel what losing Electra would be like—her own sense of it, yes, but also, and especially, what it would do to her child. It was a gut punch, both ways. (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy. (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) PreviouslyOnward we go into primary, secondary, and even tertiary characters from Northward Dreams who break away from the main narrative in a series of chapters that exist beyond the boundaries of the book's four established timelines. My role is not to play favorites with characters. My job, such as it is, lies in achieving empathy with all of them, listening to what they have to say, and, at least in the case of these chapters, talking to them. But if I were inclined to play favorites, Charley might well be my choice. You don't have to know a lot about me to know why. The most consequential male role model in my life is my stepfather. That my mother imagined something different for our lives and took us to him remains the single biggest gift I'll ever receive. That's well-covered ground. One could argue—I certainly would—that without that gift, this novel wouldn't have come to me. I would further surmise that the writing life itself might have been beyond my reach without that gift's presence, but that is an unknowable for which I am grateful. As I often say, though, there is memory (what actually happened, or what we perceive happened in our faulty hindsight), there is imagination (the fanciful stuff of world- and character-building), and there is what comes where the two meet. Charley Stidham won't tell you a thing about the life of the boy I was (and why should you be interested?). He'll tell you much about what it is to love, and to yearn, and to find gifts in the unexpected. As Charley's chapter dawns, he is arriving at the concluding paragraph of a life spent with words. Retirement. It's 2005, and he has seen a lot. There have been losses along the way, as there are for anyone with the audacity to live long enough to see them. He also has a whale of a surprise lurking at a public event he reluctantly attends: You're struck by something. You can still hear her when his mouth flies open, can see her inside his eyes and the small of his mouth, remember the way she would sometimes throw herself between the two of you in a fraught moment, until she learned to trust, and until you made your own way with him and all of you became a three-legged family and learned how to lope along together. And then... And then? You'll have to read the book. (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) Previously Now that Northward Dreams, at long last, is out in the world and available in hardcover and e-book (with the audiobook on the way!), I'm enjoying the payoff for all the lonely work of writing it and preparing it for delivery: the idea that there are people out there reading it. (Thank you!) If you're one of those people, you didn't have to go far—the very first words—to encounter one of the book's devices, for lack of a better word. Spread out among the 32 numbered chapters of the book, which encompass four timelines (1952, 1972, 2002, 2012), are nine chapters that focus on individual characters who inhabit the book. These chapters—which I've heretofore been misnaming as intercalaries—exist outside the story's established timelines and illuminate aspects of the characters that inform the whole of the narrative. They're also written in second person, a choice I expanded on in this interview with Chérie Newman: I think I went with the second-person point of view initially just to talk to them: Here's what's happening to you, what you're feeling, why it has gone the way it has. Any notion I had about changing that up went away once I saw the effect. There's an immediacy to the POV. Those characters are illuminated in ways they couldn't have been even in close third person. So that's why I did it, but this isn't really about that. (It's not expressly a craft talk.) Instead, I want to dig into who these characters are and why they spoke to me—and why they allowed me to speak to them—without giving away the essential plot, so to speak. (Before I get too far into that, about the errant use of intercalary: These chapters don't quite fit the accepted definition because they do involve main characters and are less about theme, I think, than they are about backstory. For a more traditional view of the intercalary, think of the turtle chapter of The Grapes of Wrath. I certainly do—I referenced it many years ago in a short story.) Opal goes first because...she goes. She dies, right there on Page 13: You kneel, the knees of your jeans in the mud, and you take the clipping shears from your apron pocket. You size up the job, and you pitch forward into the bush. Two crows, languid on the telephone line above, bear witness. Across the way, the hammering goes on, beating out a rhythm, a simple song for the dead and gone. Here's the thing about Opal, though: She is, in a significant way, the master key to the story, the connector of 1952 and 1972 and 2002, when she leaves us, and even 2012, when she's a full decade gone. Without Opal, the connections among Ronnie and Cherie and Nate and Electra—the four primary characters of those timelines—lack resonance. And without those four, Oscar and Anna and Charley and Brandon are four characters in search of a story. In subsequent installments of this series of posts, I'll introduce you to all of them. You'll just have to believe me that they all fit, eventually. Or read the book, please! (Be sure to note in comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.)

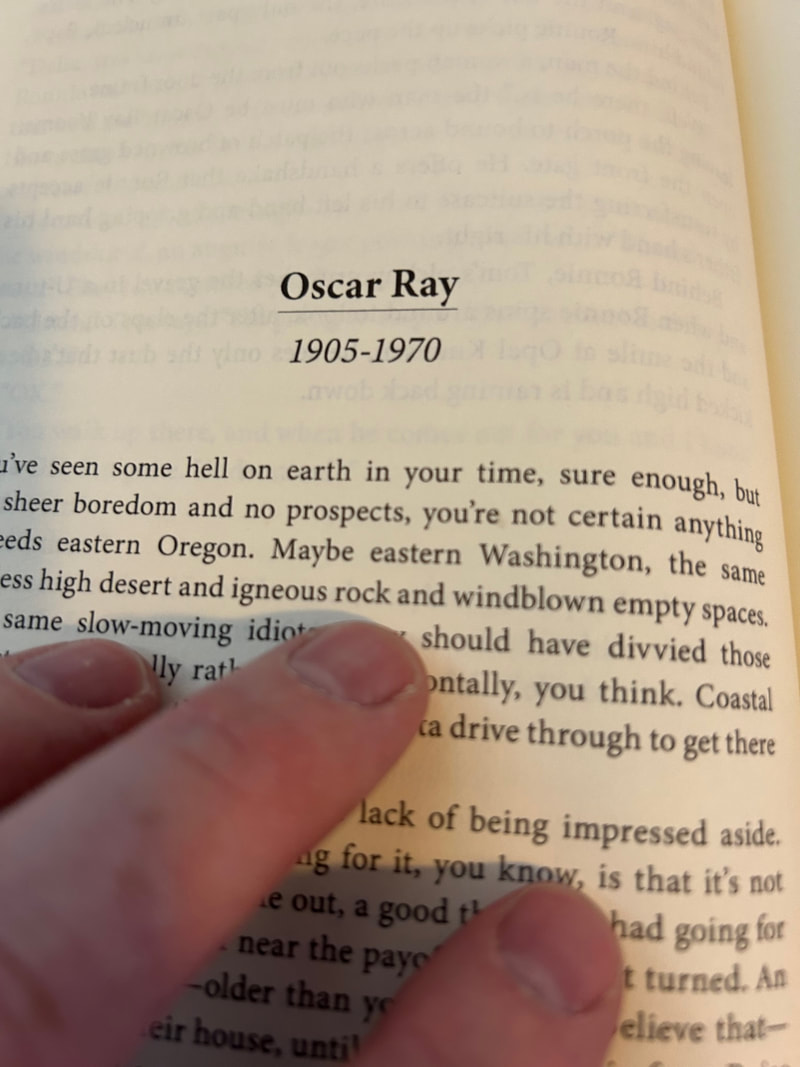

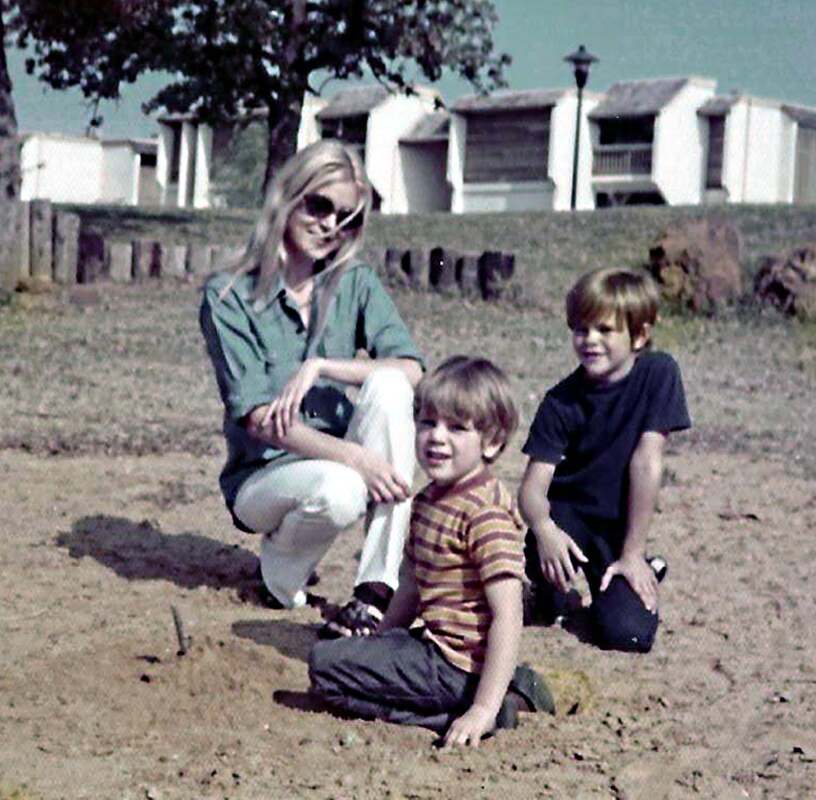

(Note: The original version of this post went up several months ago, in anticipation of the release of my new novel. That release never happened, at least not with the original publisher and not in the original form. But I feel too strongly about this piece to just let it go, so here it is, with some revisions to reflect the novel's current reality.)  I. On The Feeling My tenth novel, Northward Dreams, is just days away from its release date. I’m no more impervious to big, round numbers than anyone else is, and the imminent publication of a tenth novel—particularly when I once had serious, serious doubts that I’d ever write, much less publish, even one—is a good occasion for a bit of reflection. I’ve learned a lot about how to do this, enough that sometimes I’m even prepared to believe I’ve gotten good at it. I’ve learned a lot about humility, which forecloses any chance that I’ll linger long on “gee, I’ve gotten good at this.” (These latter-day lessons in being humbled have been particularly instructive. See the section titled On the Things That Aren't Love for more on that.) I’ve learned a lot about what’s fleeting and what’s durable. I’ve learned that it’s all about love. What that what the last bit looks like, for me, hinges on memory and imagination, the crucial elements of fiction, in my estimation, but also fairly punchless without love. It’s loving the work. Loving the characters who get conjured in the work. Loving each new project with the whole of your heart, even if—and especially if—you must love it enough to let it go. There has been a lot of this, more than I ever imagined there could be. When I get down to diagnosing why an idea didn’t take off the way I hoped it would, I almost always land on a memory to which I’ve insufficiently connected, which bogs down the imagination that is supposed to turn it into fiction, which subsequently demands the love that makes me say “this is not for me.” (If I were as good at that in my beyond-the-page life as I am in my writing life, I wouldn’t bruise so easily. But I digress.) Conversely, the idea that soars, that becomes something I see through to completion, is almost always built on the back of a memory, slathered with imagination, that becomes something else again. It’s almost magical, that feeling, even as it remains hard, word-rock-busting work to bring it forth. I love (that word again) that feeling. I chase it. Again and again and again. II. On Memory and Love A couple of years back, in an interview with Montana Quarterly (where I’ve been on the masthead since 2013), the great Larry Watson said something so profound that my greatest wish was that I’d said it first. Failing that, I cite this quote endlessly, with all due credit to Mr. Watson: I write from memory, not observation. Yet my memories are formed from observations, and then memory and imagination distort those observations into something useful for fiction and something that’s also truthful in its own way. That’s the ballgame, right there. Unsaid, but screamingly evident to anyone who has read Watson’s work, is the part where love comes in. That manifests in doing the work, in riding the work out, in achieving empathy with your characters, in knowing when to make the gradual turn from I’m writing this to engage my own need for the work to I’m writing this for someone to read someday, and thus I must be attentive to what it needs to be. Love is showing up faithfully. Love is holding at bay the world that will threaten your enthusiasm, your want-to, your ability to separate those things over which you have control and those that are mysterious variables. Love is having a standard for the work. Love is absolving yourself when, say, a pandemic swallows up your work like it never existed in the first place. It did. Your love made it manifest. Love is also forgiving yourself when you could have done better and somehow didn’t. Love is believing that you’ll do right by it the next time. Love is faith, and you’re gonna need a lot of it. Arthur Miller—I borrow only from the best—knew something about the staying power of the deeply imprinted memory. Perhaps nothing is as creatively propulsive as the blown chance, the missed boat, the shameful moment, the deep regret, the thing you ache to understand, the love you couldn’t hold. Here he is: Maybe all one can do is hope to end up with the right regrets. If you’ve had a bit of therapy—and only about eight percent of us have, which means ninety-two percent of us are in deficit—you’ve probably been told that regret is a feeling wasted on the unsustainable belief that you should have been perfect. Insofar as it applies to our lives and how we face up to them, I’m inclined to concede the point. But for the author who mines memory for stories, regret—particularly the right kind, which Miller doesn’t identify and thus is open to personal definition—is creative fuel. As I look back on ten novels, I see work and characters suffused with what I could give them through my grappling with memory and regret. Neurodivergent Edward Stanton (600 Hours of Edward, Edward Adrift, Edward Unspooled) and his fights with an illogical world. Mitch Quillen and his intractable father (The Summer Son). Hugo Hunter and his clay feet as a fighter and a father and a friend (The Fallow Season of Hugo Hunter). The Kelvig clan and their town and the pulling apart of what binds them (This Is What I Want). Sad-sack Carson McCullough and the demise of the newspaper business (Julep Street). Jo-Jo and Linus and the vagaries of attraction (You, Me & Mr. Blue Sky). Max Wendt and the status quo he doesn’t see crumbling (And It Will Be a Beautiful Life). And now, Northward Dreams, perhaps the most personal work of them all, one that required me to find the memory—and, always, the love—and enough imagination to make it something more than a transcript. So much more. So surprising in the end. So familiar that it could have kissed me. I’m in love. It keeps happening. III. On Imagination and Love How does this memory-fortified-with-imagination-backed-by-love thing work, in practical terms?I have an object lesson for that, drawn from Northward Dreams and its ingredients. The memory: If I’m prompted to give a short-hand accounting of who I am and how I got here, I say that I grew up in Texas and found my way to Montana as quickly as I could. The truth is a bit more nuanced. I wasn’t that quick. I got here when I was thirty-six years old, time enough for a dozen places in the interim that I tried, to varying degrees of success to make home. My first home, in fact, after I was born in Washington state and adopted by my parents, was in Mills, Wyoming, a little bedroom community north of Casper. For the first three years of my life, I lived in tiny clapboard house on an unpaved street, which sat across the street from one of the town’s water towers. After my mother left my father and moved us to Texas, I was largely absent from Mills save for occasional summer visits to see my dad. But the image of that water tower embedded in my psyche. Whenever I would see one like it, particularly in my suburban Texas town, I would feel the pangs of separation from my father. The imagination, in excerpt form: Ronnie goes down to the floor with his boy for a close-up view of the gas station in miniature. He watches as two round-headed figurines in a car, into which they fit like pegs, ride the elevator up to the top floor and the door opens and the car rolls out and careers down the ramp to the carpet beneath them. “Ain’t that something?” he says, and the boy squirms happily. “I got it for Christmas last year,” Nathan says. “I remember,” Ronnie says, a harmless lie, he thinks. “Hey, I saw that kid Richard, your friend, the other day. He says hello.” “He’s nice,” Nathan says. “Yeah, he’s a good kid.” Nathan bounces up and grabs his father’s hand. Ronnie clambers to his feet. “Come here,” Nathan says, tugging him. “OK.” Nathan pulls him to the window that looks out upon the suburban expanse. “See that?” “Yeah,” Ronnie says. “Buildings.” “No, that.” Nathan points, insistent. “What?” “The blue thing.” Ronnie stares down. “What blue thing?” “No, there.” The boy redirects his indicator, trying to get his father to follow the line. “The water tower?” “Yes.” “Yeah, I see it,” Ronnie says. “That’s where you live.” “It is?” “Yes. I live here. You live over there.” “No, son.” “Yes.” “No.” Ronnie makes a quarter-turn, facing the wall. He points at the blankness of it. “It looks the same as our water tower, but I live a thousand miles that way. North. Where you used to live.” He turns back to the window and points again. “That over there, that’s east. Understand?” “No.” “Well, come downstairs, Sport, and I’ll try to explain it, OK?” The love: It starts with what I feel, and have felt, for my father, a love that’s been constant but ever changing, ever shifting depending on the circumstances we find ourselves in. The unquestioning adoration I had for him when I was a little boy got replaced by an exasperated pity the more I learned about him and the more I witnessed. That, in turn, got supplanted by the responsibility I take for him in his dotage, the insistence I have of seeing him off this mortal coil and keeping fear, terror, and pain as far from him as I can. As his infirmities grow and he lashes out, I find myself with more and more days when I love him and simultaneously hope I can find a way to like him again. It’s not for wimps, this love thing. The water tower the boy points at insistently was, and is, in a Mid-Cities suburb between Fort Worth and Dallas, a town called Hurst. I used to climb into the tallest tree of my neighborhood in an adjoining town and find it on the flat horizon and try to convince myself that it was Mills, Wyoming, and that my father might be there at the base of it. I didn’t know north from east in those days. I couldn’t have envisioned the magnitude of a thousand miles. I just knew blue, cylindrical water towers and that one was in proximity of a man I missed. I tucked it all away. Years later, it came pouring out of me, a strong current of memory washed in imagination. That’s love. IV. On the Things That Aren’t Love

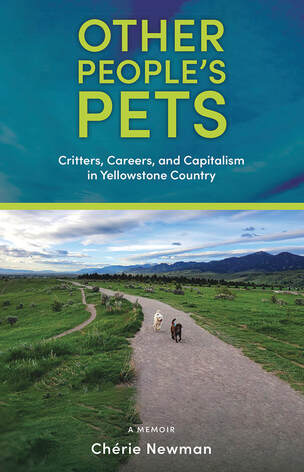

Soon after my third novel, Edward Adrift, came out in 2013, I was making enough money in royalties to grant serious consideration to trying to make a go of it as a full-time novelist. I had the big-time New York agent, a slew of foreign translations, a full calendar, and novels-in-progress lined up on the runway. My then-publisher had feted the onset of our relationship with “we want to be in the Craig Lancaster business.” That’s something—indeed, I suspect it’s something that most any author not in the one percent craves—but it’s not love. It’s validation, it’s success, it’s the fruits of one’s efforts, it’s unadulterated luck, but it’s not love. Love is what you give yourself when the royalties dry up, the big-time New York agent moves on from you, the foreign translations are harder to attract, the calendar is empty, and the ideas are taking on rust. When your publisher doesn’t want to be in the “you business” anymore. When the publisher you subsequently love makes promises that don't pan out and you pull a book just a day before it's supposed to come out, knowing you'll end up hating yourself and maybe him if you don't. And you don't want to hate anybody. Find love through that. It's not easy. But it's worth every effort you can give it. These are all things that can shoot your horse right out from under you. I’m not suggesting that you—or anyone—should just buck up and get through it, as if it’s not there, in your path like a boulder you can’t circumnavigate. Lean on your supports. Get your ass into therapy if you need it (ninety-two percent of us do!). Divert yourself with a hobby or a road trip or whatever. Take some time off, if that’s what’s calling to you. Don’t stop pushing, if pushing is what’s demanded. And while you’re doing all of that, remember the love. The love of a memory, an idea, an approach. The love of the work. The love of the characters and the settings and the structure of what you’re trying to create. The love of revising it and honing it until it’s just what you want. The love of taking the finished thing—the first or the tenth or the hundredth—and offering it up with a hopeful, open heart. I made this. I fell in love. Again. 3/2/2024 0 Comments Q&A: Chérie NewmanToday, it's my pleasure to host one of my all-time favorite human beings, Chérie Newman, as she answers some questions about her book Other People's Pets: Critters, Careers, and Capitalism in Yellowstone Country.  One of the things I like best about Chérie is how deeply she thinks about things, a tendency of hers that is written across her answers to my questions (and I promise, we're getting there soon). Then, of course, I'd have to consider the other things I like about Chérie, and the list grows. She has wide-ranging talents, she's a supportive pillar of the culture she exists in, and as I know from personal experience, she'll drive a few hours to see your play. (Well, maybe not yours. But mine. Thanks again, Chérie!) I've known her for going on two decades, and I'm continually impressed by the breadth of what she dips into and becomes proficient at doing. Without further ado, then, here's Chérie Newman and her thoughts about Other People's Pets...  I'm fascinated with the resumption of your—not career, really, but work—as a pet sitter after a long break from it. What prompted that? Was it like riding a bike, as the saying goes, or were there rigors to the second go-round you didn't anticipate? The resumption of my work as a pet sitter happened during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Before March of 2020, I earned most of my freelance income as a podcast editor, working with audio files recorded during live events. Then, suddenly, there were no live events. No live events meant no money for me. My hasty reaction to the loss of income was to accept a job as an office manager. Yuck!! I do not like office work. So, I quit that after a year and agreed to become a subcontractor for a Bozeman pet sitter who had way more work than she could handle. This was the end of 2021, when many people were starting to travel again. She started sending me on interviews and that’s when the fun began. Although, I’ve taken care of other people’s pets all my life, it was mostly for friends and family. Right now, I can only think of four or five people—“clients”—who hired me as a professional, home-stay pet sitter between 1990 and 2022. The rigors, as you say, of these new situations were complicated and multi-faceted. Most of the people I worked for were nice. But they weren't paying a lot, and their expectations were high. And, I have to say, that even though they were paying me two or three times the amount I’d earned before, the average hourly rate came out to about $4 an hour. Four dollars an hour for being on duty 24/7 is not great. Especially when you factor in responsibilities for other people’s property, package delivery (Why do people order stuff when they know they’re leaving town?), invisible fences that fail and other high-stress events, and the fact that most of the houses were located far from central Bozeman. The $4/hr didn’t include fuel and other travel expenses. It didn’t include travel expenses incurred when I drove 30 miles for an interview. At what point did you realize you were gathering book-worthy material? When my friends started yelling, “You have to write a book about this!” every time I told stories about my experiences at dinner parties. I love how the book uses something as seemingly picayune as pet sitting to explore much deeper themes about where we live and how. What are the big takeaways for you regarding our relationships with our animals and the places we call home? Well, first let me say that I’ve noticed a trend: pets are now treated more as children than animals. The love-of-my-life dog, MooJee, lived with me for 15 years, but I never considered her my child. She was a beloved companion and, of course, I did everything I could to keep her happy and safe. She was dependent on me for that. But. She. Was. A. Dog. During my recent pet sitting adventures I noticed an increase in bad pet behavior. Lots of neurotic animals, made so, I believe, by their people. For example, I took care of two Irish setters whose daily schedule included cocktail weenies at 4:30 p.m. and an 8 o’clock bedtime. They also expected their lunch at 2 p.m. and acted out if it wasn’t served on time. By acting out I mean behavior such as opening the freezer and letting food thaw or dragging kitchen scraps out of the sink and throwing them all over the floor or hiding car keys under a dog bed. The places we (some of us, anyway) call home seem to be much more temporary than they were in the past. And people who have more than one house/home often leave their animals with a pet sitter while they live somewhere else for long periods of time or take pets with them and leave their houses empty. I wonder about all the huge, often uninhabited houses standing on Montana land, places that used to support wildlife, land upon which wildlife can no longer migrate or find food. What have you learned about humans through their pets? I’ve noticed an increase in the human need for external approval, which some people try to extract from their pets. Kind of crazy. Pet pics on social media attract lots of attention, which offers online validation for people. But of course, pet pictures and stories are entertaining and fun. We can’t safely post images of children online these days. Maybe our pets are stand-ins? And then there’s the amount of money people in the U. S. spend on their pets—nearly 150 billion dollars in 2023, according to Market Watch. So, your question is insightful. Are humans devolving as the status of pets rises? Are pets usurping control of our behavior and finances? What's next for you (wide-open question; I'm talking books, music, vocation, avocation, etc., etc.)? Ha! Thanks for asking. My mind is always blazing with new ideas. I just published another book, Do It in the Kitchen: a step-by-step guide to recording your life stories (or someone else’s). When they find out I’m an audio producer, people often ask me questions about recording audiobooks and oral histories, or want to know how to create a podcast. This book will help anyone who has those kinds of urges. I just finished writing a children’s book about a dog who saves his family from a house fire (true story). The process of finding an illustrator has been, well…interesting. I wish I had better drawing skills. (But maybe not because then I’d draw and I have too much other stuff to do.) My list of podcast clients has grown again during the past few months, so I do that editing/production work as it comes in. I’m also a musician and play in a band called Ukephoria Montana. We perform public and private concerts and participate in twice-monthly sing-along sessions at the Gallatin Rest Home. I participate in a songwriting collaborative and write songs on my own, as well. Every so often, I land a public speaking or workshop facilitator gig. I can’t name names, but I’m talking with an educational group about the possibility of producing a podcast series for them. It would be a dream gig for me. All fingers crossed, please. Since I’m self-employed, the marketing and PR tasks are endless. There’s always something new to learn. And, oh yeah, I read a lot of books and listen to several audiobooks a week. Yep, a week. Recent favorites:

What am I missing? What else would you like to say?

Oh, you are a brave man. I always have something else to say and usually say way too much. But I’ll stop now, except for this and this:

Wait! One more thing: Thank you for these questions and for reading my book. Oh, and another thing: I’m champing (yes, champing — to more precisely convey “impatience” — not chomping) at the bit to talk with you about your new novel, Dreaming Northward. Okay, that’s all my things. Maybe. But you should stop reading now. 2/7/2024 2 Comments Mind the LadderThere is a point to this, I promise, but I can't get there without first telling a sweet little story. So just bear with me, please... I've been contacting old friends on Facebook and other social sites, collecting mailing addresses. I'm having a literary reading and book signing this May in Texas, my first one in my home state in many years, and seldom does one get a chance to gather his foundational friends and acquaintances in one place and say thank you, for everything. I'm going to take that shot. The address search eventually led me to a man named Jim Fuquay, and that's where both the sweet little story and the point come in. Jim, an avid gardener, told me he was fighting the doldrums of February by reconnecting with old friends, that it had been a nifty little coincidence that I had reached out when I did. He asked me to give him a call, and I did, and let me tell you, it's been a long time since I enjoyed a half-hour as much as I did that one. But that's not the point. Jim was the first person to give me steady work in my first chosen field. It's been many years since that happened—thirty-five of them as of November of last year—and we both are, to state the obvious, much older now. We established on the call that he's eighteen years my elder (I honestly never knew the age gap, only that when we met, he was a fully mature man and I was...not). Eighteen years doesn't seem like that many now that I'm breathing heavily on age 54, but when I was eighteen years old and standing in his office, asking to be turned loose on writing newspaper articles, he sure seemed like an elder. An exceptionally kind and accessible elder, yes, but an elder just the same. Here's how I described Jim's decision to hire me in a public lecture I gave several years ago: The month before, I’d answered an ad in the Star-Telegram seeking correspondents for weekly community sections of the newspaper. I was eighteen, and the hiring editor wasn’t much interested in me until he read my clips. ... He gave me a job: the lowest-level, worst-paying, crappiest-assignment kind of writing job there was, but a job. Our deal was that I’d keep plugging away at school, he’d feed me a story opportunity every week or so, pay me $50 per, and let me build up a body of work. By late December...I had a story on the front page of the main newspaper. I was 18 years old, and I’d climbed a mountaintop of sorts. I wasn’t in the place I’d wanted to be, and I hadn’t made much headway into my half of the bargain with my boss, but I was getting somewhere. So many somewheres, as it turned out. During our phone call, I couldn't help reflecting on something that has crossed my mind plenty of times in my long working life, when I've considered how I got from there to here (and all the destinations in between): Jim didn't have to hire me. He could have given me a cursory look and sent me on my way, and his life would have been continued apace. Mine changed that day. A life has some number of true turning points, and that was one of mine. What Jim did that was so kind, so basic, and yet so uncommon is that he took a good look at me and imagined what I could be rather than fixating on what I was not. I was eighteen; I had no track record. I had only potential and gumption. Jim said yes to a kid who badly needed to hear that word. This is my point. And this is my plea: If ever you're in a position to take a gamble on someone, to surprise someone with a "yes" when you could save yourself time and aggravation with a brush-off, breathe that "yes" into the air. It could be the break that unlocks everything else for the recipient of that welcome word. I talk about this a lot with a friend with whom I lunch regularly. Where is the ladder anymore? What's a kid who doesn't emerge from the traditional mold supposed to do? What is a career and how does anybody get one?

When I was eighteen years old, in 1988, I was audacious in seeking a job, but at least I knew where to look. I had my eyes on a journalism career, and the procession into one was fairly well established at that point. You went to college. You gathered some experience. You did an internship. You caught on somewhere and started swimming. If you didn't read my public lecture, linked above, perhaps take a look now. I inverted that formula. More than that, I yanked it up by its feet and bounced it off its head. I bombed the college part, eventually. Internship? Never had one, at least not in a traditional sense. Experience? Not so much, no, not at that point. I came to Jim that fall bearing clips of stories I'd written for my high school paper. Not exactly a bastion of journalistic excellence. I came to him with chutzpah because chutzpah was all I had. Still, he said yes. He knew where the ladder was, knew he'd climbed it himself, knew the responsibility he had to make sure it was in good stead for someone else. He'd gained some latitude in his profession and spent some of it on me. A simple word, "yes," with fraught possibilities and potentially difficult outcomes. But what's the good of having a "yes" in your pocket if you're not willing to draw it out and slap it on the table? As we rang off, I thanked him for taking a chance back then. "I've never regretted it," he said. Neither have I, Jim. Neither have I. 2/3/2024 0 Comments Texas.I moved to Texas when I was three years old. No one consulted me, and I wasn't happy about it, but Texas and I, we found our way. In time, I came to view that move as the most consequential event in my life. When I left Texas for the first time, I was fifteen years old, about to be a sophomore in high school, and I made a snap decision that I'd like to live with my father in rural New Mexico. He'd just been through a divorce, a particularly bad one, and I thought maybe he needed me. It didn't take. A lot of lessons in that, some that got under my skin immediately and others that steeped for many years before I understood. Among the latter group, probably one of the most important lessons: You can't fix for someone else what he must mend on his own. By the end of December, I was back home in North Texas, where I belonged, even if I still felt the fit was a little tight. When I left Texas for the second time, I was twenty-one, and I pointed my nose toward just about the farthest-away dot on my map. I went to Kenai, Alaska, for a sports editor's job. That didn't take, either--though some vital friendships did—and I came scurrying back not six months later. When I left Texas for the third time, I was twenty-three, and it was a job I left behind, a fairly miserable nine-month stint in Texarkana. Texas and I, we were living together uneasily amid irreconcilable differences. I worked at night on the Texas side, then hustled back across the line to Arkansas to set down my head. When I had a chance to leave Texas, off to Kentucky I went. When I left Texas for the fourth—and, as yet, final—time, I was thirty years old and adrift, in the midst of one of those Worst Years Ever that seem to surface every decade. I'd bounced from San Jose to San Antonio, and I'd found Texas to be what it always had been: inscrutable, beautiful, alluring, interesting, and not for me. Back to San Jose I went, but first with a three-month misdirection in Olympia, Washington, and it's like I said: bad year. This is all to say that I've left Texas a lot. But Texas has never left me. The math doesn't lie. Texas had me for most of eighteen years, then nine months, then eight months. Nineteen and a half years, let's call it. Add in various visits over the years—can you really leave a place that harbors your parents and your siblings and your formative memories and some of the best friends you've ever had?—and the total still falls short of twenty years, but let's round it up. Fine. Twenty years of Texas. I'm fifty-three, and on the cusp of the next number up. The scales tip heavily toward everywhere else. Here before too long, Montana will sink its years deeper into me than Texas ever did. It already has more of my heart, more influence on my creativity, a bigger share of my identity. Still, Texas abides. Still, Texas claims me. Still, I claim Texas. Those holds are coming up through my work first, which means they're coming up in my memories. My latest work is drenched in Texas, even if most of it unfolds farther north. There was no way to imagine Nathan Ray, the central character of the ensemble, without first cozying up to the Texas I knew as a boy, then conjuring a backstory where the Texas he knows is a backdrop of pain and disillusionment and gifts he cannot yet see. It's in the next book—the one with a title in flux, the one that may emerge in 2025, or maybe '26—that Texas takes a star turn, a place both abandoned and returned to. Here's a snippet: Texas was gone, falling behind us a mile a minute, and I was relieved and scared all at the same time. You leave Texas little by little and then all at once, yes, but Texas is also a magnet—a big, southerly magnet pulling at everyone else in the country with myths and manufactured romance and jobs and cheap living and low taxes. You can get away, but can you ever really leave? My answer, beyond the bounds of fiction? It's complicated. You can leave, sure. But you come back. The only thing is, I've never made a return stick. But it's early yet. I'm still upright and breathing. In the foreseeable term, of course, I'm not going anywhere. I live in Montana, I love living in Montana, and the father with whom I couldn't live in 1985 really does need me now. He lives in Montana. As long as he draws breath, and probably longer, here I'll be.

But I can't quit Texas, and unlike the answer I'd have given you twenty years ago, I don't want to. It's in my head and my heart and my memories, and the last of those is the most essential ingredient in doing this thing I do. That, I believe, is why Texas seems so insistent these days, like a song that I can't get out of my ears. It's having its say in my work, and I'm making room for it there. Perhaps, in some future I cannot yet see, I'll make other accommodations for it, too. Occasionally, either not knowing my history or not caring, a friend or acquaintance will say something cutting about the place that shaped my boyhood, and thus my life. And I'll cringe, because the cuts are easy enough to administer when Texas serves up such ridiculous stereotypes, such a bloody history, such casually cruel politics. On a day when I can find patience and indulgence for a friend's carelessness, I will say, OK, yes, but Texas is also a vast and beautiful place, full of beautiful people who contain multitudes. Texas isn't made for anyone's tidy little box. It's destined to spill out from whatever attempts to contain it. In short, it cannot be seen in simplicities when its complexities abound. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed