|

5/21/2024 0 Comments Texas. Redux.

I wrote about my home* state several weeks ago. It was a wide-angle, pulled-back view, and I thought I'd unloaded what was in my heart and my head. But here I go again...

No, really, here I go. It's a quick trip this time, not my usual two-day drive down, weeklong stay, and two-day drive back. I'm going for a reading and signing at a bookstore in Keller, the once-sleepy town just north of where I grew up. Like other parts of the North Texas I once knew, it doesn't really match up with my memories anymore. It's bigger, more congested, more diverse, more interesting.

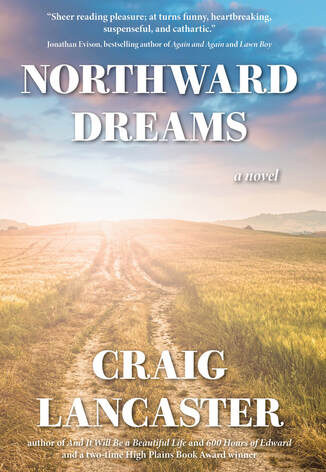

The book I'm taking with me, Northward Dreams, is the most personal piece of fiction I've ever written. The best thing I've ever written, too, not that anyone should trust me to judge such a thing. I'm proud of it. I'm proud of how I willed it into existence. And I really, really want to share it with the people who underpin it, in ways subtle and overt. They're in the book, all of them, whether they would recognize themselves or not. They're in it because they're in me, in the memories I carry around.

To that end, I sent out about 100 postcards earlier this year, addressed to people from across the years I spent in Texas: classmates, old neighbors, former bosses, teachers, colleagues, friends, former lovers. I asked them to come out and see me and to meet this book, to renew acquaintances or to prolong friendships that never ran dry. I'm hoping to see a constellation of faces I recognize come Saturday, but I've also put this event squarely in a holiday weekend, so who knows? I haven't always done a wonderful job of staying in touch as I've wandered the country, looking for the place I'd call home. I found it, years ago. But I've also come to realize that the place I'm from—as much as I'm from anywhere—is also home and always will be.

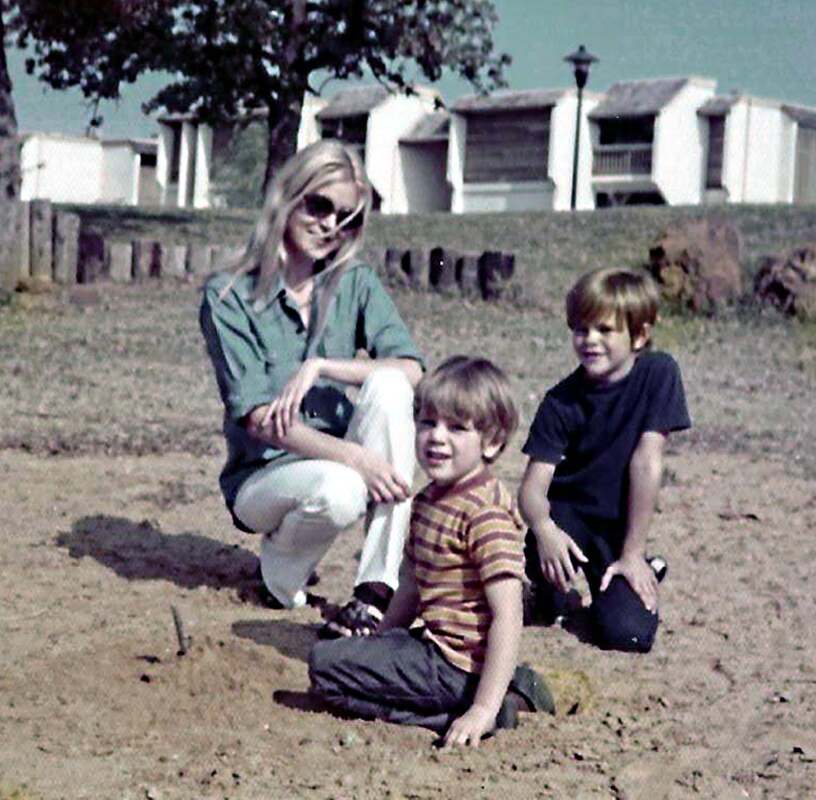

When I say Northward Dreams is my most personal book, I'm thinking, among other things, about this snippet from one of the four timelines the novel covers. Here, in 1972, Electra and her little boy have arrived at their new home in Texas:

After they’ve gone downstairs, after Electra has made her assessment of the pantry, after she’s pictured the days stretched out before them, after Nathan, red-faced and watery-eyed, has come down and asked for a glass of water, after Charley has fetched the rest of their things and stacked them by the door for sorting out later, after they’ve come back up the stairs, quieter, the three of them lie askew on the king bed. Charley is on his side, head propped up by an angular arm. Electra lies far opposite of him, attentive to her son, and Nathan sleeps in between, curled like a kitten’s paw and under a loose blanket. Electra reaches across the distance, and Charley takes her hand. “Probably not what you expected.” “It’s everything I expected,” he whispers. “You?” “It’s what I want,” she says. “Me, too.” “He’s really a good boy,” she says. “I know.” “It’s a lot to deal with.” “It is.” Charley sits himself up, careful not to jostle the boy. “Kids are resilient, though. I ever tell you about when we moved from Vernon to Wichita Falls?” “No. I’d remember.” “You went through both towns,” he says. “I know.” “I wish I could have been there.” “I know,” she says. “Fifty-some miles, might as well have been moving from earth to the moon. I was nine. Everything I knew, every friend I had, they were all in Vernon, but my dad, he was a history teacher, and the high school in Wichita Falls, they offered him $15 more a week, so we moved. I didn’t have any say.” “Had to be hard at that age.” She’s thinking now of Nathan’s best friends, the Miles boy two doors down and the Fletcher kid, the one she doesn’t much like but whom Nathan adores, and how she plucked him up and took him away without his getting to say goodbye. She hurts for him in a way that she hasn’t allowed herself to think about until now. “Hard at any age,” Charley says. “But the thing is, in the end, I made new friends. Wichita Falls became home, every bit as much as Vernon had been. I adjusted. He’ll adjust, too.” “Tomorrow,” she says, more thoughts she’s held at bay rushing toward her now. Enrolling Nathan in school. Finding a job. Learning where the supermarket is. “It’ll all get done,” he says, as if inside her head. It’s a talent he has. She leans across and kisses him for the first time. Where all of that comes from is both imagination and memory, little snippets that I heard, others I conjured, all of it front and center in my brain, ready to be accessed when I got hold of a story that needed it. This story. This place. Another time of life, forever salient because the decisions that were made had such gravity to them that their effects radiated out to lives yet to be launched. It's powerful stuff, fiction. Often more powerful than the real life that informs it.

0 Comments

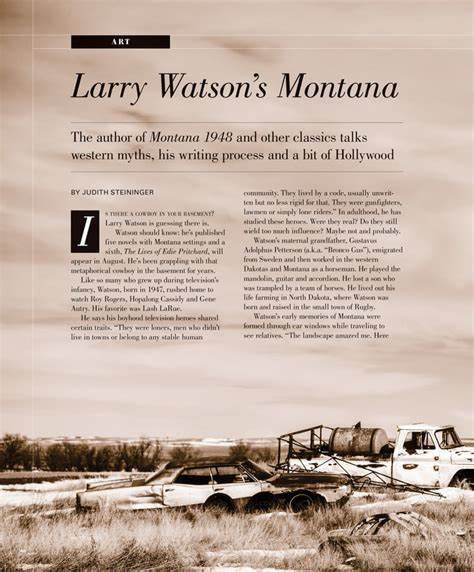

(Note: The original version of this post went up several months ago, in anticipation of the release of my new novel. That release never happened, at least not with the original publisher and not in the original form. But I feel too strongly about this piece to just let it go, so here it is, with some revisions to reflect the novel's current reality.)  I. On The Feeling My tenth novel, Northward Dreams, is just days away from its release date. I’m no more impervious to big, round numbers than anyone else is, and the imminent publication of a tenth novel—particularly when I once had serious, serious doubts that I’d ever write, much less publish, even one—is a good occasion for a bit of reflection. I’ve learned a lot about how to do this, enough that sometimes I’m even prepared to believe I’ve gotten good at it. I’ve learned a lot about humility, which forecloses any chance that I’ll linger long on “gee, I’ve gotten good at this.” (These latter-day lessons in being humbled have been particularly instructive. See the section titled On the Things That Aren't Love for more on that.) I’ve learned a lot about what’s fleeting and what’s durable. I’ve learned that it’s all about love. What that what the last bit looks like, for me, hinges on memory and imagination, the crucial elements of fiction, in my estimation, but also fairly punchless without love. It’s loving the work. Loving the characters who get conjured in the work. Loving each new project with the whole of your heart, even if—and especially if—you must love it enough to let it go. There has been a lot of this, more than I ever imagined there could be. When I get down to diagnosing why an idea didn’t take off the way I hoped it would, I almost always land on a memory to which I’ve insufficiently connected, which bogs down the imagination that is supposed to turn it into fiction, which subsequently demands the love that makes me say “this is not for me.” (If I were as good at that in my beyond-the-page life as I am in my writing life, I wouldn’t bruise so easily. But I digress.) Conversely, the idea that soars, that becomes something I see through to completion, is almost always built on the back of a memory, slathered with imagination, that becomes something else again. It’s almost magical, that feeling, even as it remains hard, word-rock-busting work to bring it forth. I love (that word again) that feeling. I chase it. Again and again and again. II. On Memory and Love A couple of years back, in an interview with Montana Quarterly (where I’ve been on the masthead since 2013), the great Larry Watson said something so profound that my greatest wish was that I’d said it first. Failing that, I cite this quote endlessly, with all due credit to Mr. Watson: I write from memory, not observation. Yet my memories are formed from observations, and then memory and imagination distort those observations into something useful for fiction and something that’s also truthful in its own way. That’s the ballgame, right there. Unsaid, but screamingly evident to anyone who has read Watson’s work, is the part where love comes in. That manifests in doing the work, in riding the work out, in achieving empathy with your characters, in knowing when to make the gradual turn from I’m writing this to engage my own need for the work to I’m writing this for someone to read someday, and thus I must be attentive to what it needs to be. Love is showing up faithfully. Love is holding at bay the world that will threaten your enthusiasm, your want-to, your ability to separate those things over which you have control and those that are mysterious variables. Love is having a standard for the work. Love is absolving yourself when, say, a pandemic swallows up your work like it never existed in the first place. It did. Your love made it manifest. Love is also forgiving yourself when you could have done better and somehow didn’t. Love is believing that you’ll do right by it the next time. Love is faith, and you’re gonna need a lot of it. Arthur Miller—I borrow only from the best—knew something about the staying power of the deeply imprinted memory. Perhaps nothing is as creatively propulsive as the blown chance, the missed boat, the shameful moment, the deep regret, the thing you ache to understand, the love you couldn’t hold. Here he is: Maybe all one can do is hope to end up with the right regrets. If you’ve had a bit of therapy—and only about eight percent of us have, which means ninety-two percent of us are in deficit—you’ve probably been told that regret is a feeling wasted on the unsustainable belief that you should have been perfect. Insofar as it applies to our lives and how we face up to them, I’m inclined to concede the point. But for the author who mines memory for stories, regret—particularly the right kind, which Miller doesn’t identify and thus is open to personal definition—is creative fuel. As I look back on ten novels, I see work and characters suffused with what I could give them through my grappling with memory and regret. Neurodivergent Edward Stanton (600 Hours of Edward, Edward Adrift, Edward Unspooled) and his fights with an illogical world. Mitch Quillen and his intractable father (The Summer Son). Hugo Hunter and his clay feet as a fighter and a father and a friend (The Fallow Season of Hugo Hunter). The Kelvig clan and their town and the pulling apart of what binds them (This Is What I Want). Sad-sack Carson McCullough and the demise of the newspaper business (Julep Street). Jo-Jo and Linus and the vagaries of attraction (You, Me & Mr. Blue Sky). Max Wendt and the status quo he doesn’t see crumbling (And It Will Be a Beautiful Life). And now, Northward Dreams, perhaps the most personal work of them all, one that required me to find the memory—and, always, the love—and enough imagination to make it something more than a transcript. So much more. So surprising in the end. So familiar that it could have kissed me. I’m in love. It keeps happening. III. On Imagination and Love How does this memory-fortified-with-imagination-backed-by-love thing work, in practical terms?I have an object lesson for that, drawn from Northward Dreams and its ingredients. The memory: If I’m prompted to give a short-hand accounting of who I am and how I got here, I say that I grew up in Texas and found my way to Montana as quickly as I could. The truth is a bit more nuanced. I wasn’t that quick. I got here when I was thirty-six years old, time enough for a dozen places in the interim that I tried, to varying degrees of success to make home. My first home, in fact, after I was born in Washington state and adopted by my parents, was in Mills, Wyoming, a little bedroom community north of Casper. For the first three years of my life, I lived in tiny clapboard house on an unpaved street, which sat across the street from one of the town’s water towers. After my mother left my father and moved us to Texas, I was largely absent from Mills save for occasional summer visits to see my dad. But the image of that water tower embedded in my psyche. Whenever I would see one like it, particularly in my suburban Texas town, I would feel the pangs of separation from my father. The imagination, in excerpt form: Ronnie goes down to the floor with his boy for a close-up view of the gas station in miniature. He watches as two round-headed figurines in a car, into which they fit like pegs, ride the elevator up to the top floor and the door opens and the car rolls out and careers down the ramp to the carpet beneath them. “Ain’t that something?” he says, and the boy squirms happily. “I got it for Christmas last year,” Nathan says. “I remember,” Ronnie says, a harmless lie, he thinks. “Hey, I saw that kid Richard, your friend, the other day. He says hello.” “He’s nice,” Nathan says. “Yeah, he’s a good kid.” Nathan bounces up and grabs his father’s hand. Ronnie clambers to his feet. “Come here,” Nathan says, tugging him. “OK.” Nathan pulls him to the window that looks out upon the suburban expanse. “See that?” “Yeah,” Ronnie says. “Buildings.” “No, that.” Nathan points, insistent. “What?” “The blue thing.” Ronnie stares down. “What blue thing?” “No, there.” The boy redirects his indicator, trying to get his father to follow the line. “The water tower?” “Yes.” “Yeah, I see it,” Ronnie says. “That’s where you live.” “It is?” “Yes. I live here. You live over there.” “No, son.” “Yes.” “No.” Ronnie makes a quarter-turn, facing the wall. He points at the blankness of it. “It looks the same as our water tower, but I live a thousand miles that way. North. Where you used to live.” He turns back to the window and points again. “That over there, that’s east. Understand?” “No.” “Well, come downstairs, Sport, and I’ll try to explain it, OK?” The love: It starts with what I feel, and have felt, for my father, a love that’s been constant but ever changing, ever shifting depending on the circumstances we find ourselves in. The unquestioning adoration I had for him when I was a little boy got replaced by an exasperated pity the more I learned about him and the more I witnessed. That, in turn, got supplanted by the responsibility I take for him in his dotage, the insistence I have of seeing him off this mortal coil and keeping fear, terror, and pain as far from him as I can. As his infirmities grow and he lashes out, I find myself with more and more days when I love him and simultaneously hope I can find a way to like him again. It’s not for wimps, this love thing. The water tower the boy points at insistently was, and is, in a Mid-Cities suburb between Fort Worth and Dallas, a town called Hurst. I used to climb into the tallest tree of my neighborhood in an adjoining town and find it on the flat horizon and try to convince myself that it was Mills, Wyoming, and that my father might be there at the base of it. I didn’t know north from east in those days. I couldn’t have envisioned the magnitude of a thousand miles. I just knew blue, cylindrical water towers and that one was in proximity of a man I missed. I tucked it all away. Years later, it came pouring out of me, a strong current of memory washed in imagination. That’s love. IV. On the Things That Aren’t Love

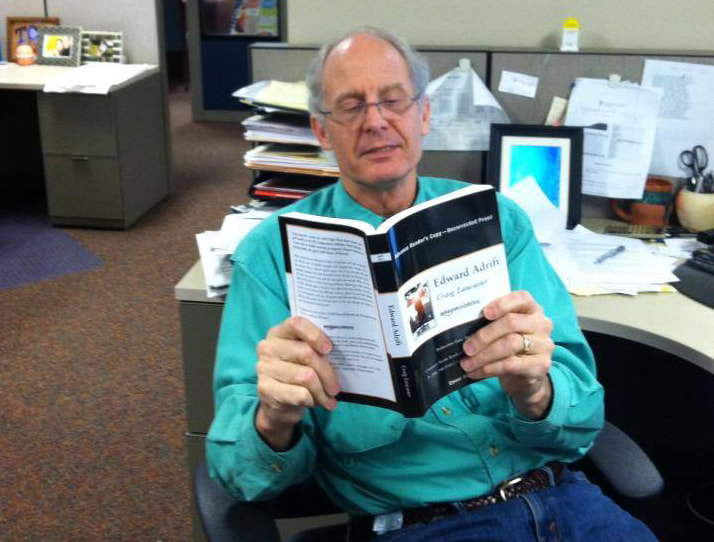

Soon after my third novel, Edward Adrift, came out in 2013, I was making enough money in royalties to grant serious consideration to trying to make a go of it as a full-time novelist. I had the big-time New York agent, a slew of foreign translations, a full calendar, and novels-in-progress lined up on the runway. My then-publisher had feted the onset of our relationship with “we want to be in the Craig Lancaster business.” That’s something—indeed, I suspect it’s something that most any author not in the one percent craves—but it’s not love. It’s validation, it’s success, it’s the fruits of one’s efforts, it’s unadulterated luck, but it’s not love. Love is what you give yourself when the royalties dry up, the big-time New York agent moves on from you, the foreign translations are harder to attract, the calendar is empty, and the ideas are taking on rust. When your publisher doesn’t want to be in the “you business” anymore. When the publisher you subsequently love makes promises that don't pan out and you pull a book just a day before it's supposed to come out, knowing you'll end up hating yourself and maybe him if you don't. And you don't want to hate anybody. Find love through that. It's not easy. But it's worth every effort you can give it. These are all things that can shoot your horse right out from under you. I’m not suggesting that you—or anyone—should just buck up and get through it, as if it’s not there, in your path like a boulder you can’t circumnavigate. Lean on your supports. Get your ass into therapy if you need it (ninety-two percent of us do!). Divert yourself with a hobby or a road trip or whatever. Take some time off, if that’s what’s calling to you. Don’t stop pushing, if pushing is what’s demanded. And while you’re doing all of that, remember the love. The love of a memory, an idea, an approach. The love of the work. The love of the characters and the settings and the structure of what you’re trying to create. The love of revising it and honing it until it’s just what you want. The love of taking the finished thing—the first or the tenth or the hundredth—and offering it up with a hopeful, open heart. I made this. I fell in love. Again. 2/7/2024 2 Comments Mind the LadderThere is a point to this, I promise, but I can't get there without first telling a sweet little story. So just bear with me, please... I've been contacting old friends on Facebook and other social sites, collecting mailing addresses. I'm having a literary reading and book signing this May in Texas, my first one in my home state in many years, and seldom does one get a chance to gather his foundational friends and acquaintances in one place and say thank you, for everything. I'm going to take that shot. The address search eventually led me to a man named Jim Fuquay, and that's where both the sweet little story and the point come in. Jim, an avid gardener, told me he was fighting the doldrums of February by reconnecting with old friends, that it had been a nifty little coincidence that I had reached out when I did. He asked me to give him a call, and I did, and let me tell you, it's been a long time since I enjoyed a half-hour as much as I did that one. But that's not the point. Jim was the first person to give me steady work in my first chosen field. It's been many years since that happened—thirty-five of them as of November of last year—and we both are, to state the obvious, much older now. We established on the call that he's eighteen years my elder (I honestly never knew the age gap, only that when we met, he was a fully mature man and I was...not). Eighteen years doesn't seem like that many now that I'm breathing heavily on age 54, but when I was eighteen years old and standing in his office, asking to be turned loose on writing newspaper articles, he sure seemed like an elder. An exceptionally kind and accessible elder, yes, but an elder just the same. Here's how I described Jim's decision to hire me in a public lecture I gave several years ago: The month before, I’d answered an ad in the Star-Telegram seeking correspondents for weekly community sections of the newspaper. I was eighteen, and the hiring editor wasn’t much interested in me until he read my clips. ... He gave me a job: the lowest-level, worst-paying, crappiest-assignment kind of writing job there was, but a job. Our deal was that I’d keep plugging away at school, he’d feed me a story opportunity every week or so, pay me $50 per, and let me build up a body of work. By late December...I had a story on the front page of the main newspaper. I was 18 years old, and I’d climbed a mountaintop of sorts. I wasn’t in the place I’d wanted to be, and I hadn’t made much headway into my half of the bargain with my boss, but I was getting somewhere. So many somewheres, as it turned out. During our phone call, I couldn't help reflecting on something that has crossed my mind plenty of times in my long working life, when I've considered how I got from there to here (and all the destinations in between): Jim didn't have to hire me. He could have given me a cursory look and sent me on my way, and his life would have been continued apace. Mine changed that day. A life has some number of true turning points, and that was one of mine. What Jim did that was so kind, so basic, and yet so uncommon is that he took a good look at me and imagined what I could be rather than fixating on what I was not. I was eighteen; I had no track record. I had only potential and gumption. Jim said yes to a kid who badly needed to hear that word. This is my point. And this is my plea: If ever you're in a position to take a gamble on someone, to surprise someone with a "yes" when you could save yourself time and aggravation with a brush-off, breathe that "yes" into the air. It could be the break that unlocks everything else for the recipient of that welcome word. I talk about this a lot with a friend with whom I lunch regularly. Where is the ladder anymore? What's a kid who doesn't emerge from the traditional mold supposed to do? What is a career and how does anybody get one?

When I was eighteen years old, in 1988, I was audacious in seeking a job, but at least I knew where to look. I had my eyes on a journalism career, and the procession into one was fairly well established at that point. You went to college. You gathered some experience. You did an internship. You caught on somewhere and started swimming. If you didn't read my public lecture, linked above, perhaps take a look now. I inverted that formula. More than that, I yanked it up by its feet and bounced it off its head. I bombed the college part, eventually. Internship? Never had one, at least not in a traditional sense. Experience? Not so much, no, not at that point. I came to Jim that fall bearing clips of stories I'd written for my high school paper. Not exactly a bastion of journalistic excellence. I came to him with chutzpah because chutzpah was all I had. Still, he said yes. He knew where the ladder was, knew he'd climbed it himself, knew the responsibility he had to make sure it was in good stead for someone else. He'd gained some latitude in his profession and spent some of it on me. A simple word, "yes," with fraught possibilities and potentially difficult outcomes. But what's the good of having a "yes" in your pocket if you're not willing to draw it out and slap it on the table? As we rang off, I thanked him for taking a chance back then. "I've never regretted it," he said. Neither have I, Jim. Neither have I. 2/3/2024 0 Comments Texas.I moved to Texas when I was three years old. No one consulted me, and I wasn't happy about it, but Texas and I, we found our way. In time, I came to view that move as the most consequential event in my life. When I left Texas for the first time, I was fifteen years old, about to be a sophomore in high school, and I made a snap decision that I'd like to live with my father in rural New Mexico. He'd just been through a divorce, a particularly bad one, and I thought maybe he needed me. It didn't take. A lot of lessons in that, some that got under my skin immediately and others that steeped for many years before I understood. Among the latter group, probably one of the most important lessons: You can't fix for someone else what he must mend on his own. By the end of December, I was back home in North Texas, where I belonged, even if I still felt the fit was a little tight. When I left Texas for the second time, I was twenty-one, and I pointed my nose toward just about the farthest-away dot on my map. I went to Kenai, Alaska, for a sports editor's job. That didn't take, either--though some vital friendships did—and I came scurrying back not six months later. When I left Texas for the third time, I was twenty-three, and it was a job I left behind, a fairly miserable nine-month stint in Texarkana. Texas and I, we were living together uneasily amid irreconcilable differences. I worked at night on the Texas side, then hustled back across the line to Arkansas to set down my head. When I had a chance to leave Texas, off to Kentucky I went. When I left Texas for the fourth—and, as yet, final—time, I was thirty years old and adrift, in the midst of one of those Worst Years Ever that seem to surface every decade. I'd bounced from San Jose to San Antonio, and I'd found Texas to be what it always had been: inscrutable, beautiful, alluring, interesting, and not for me. Back to San Jose I went, but first with a three-month misdirection in Olympia, Washington, and it's like I said: bad year. This is all to say that I've left Texas a lot. But Texas has never left me. The math doesn't lie. Texas had me for most of eighteen years, then nine months, then eight months. Nineteen and a half years, let's call it. Add in various visits over the years—can you really leave a place that harbors your parents and your siblings and your formative memories and some of the best friends you've ever had?—and the total still falls short of twenty years, but let's round it up. Fine. Twenty years of Texas. I'm fifty-three, and on the cusp of the next number up. The scales tip heavily toward everywhere else. Here before too long, Montana will sink its years deeper into me than Texas ever did. It already has more of my heart, more influence on my creativity, a bigger share of my identity. Still, Texas abides. Still, Texas claims me. Still, I claim Texas. Those holds are coming up through my work first, which means they're coming up in my memories. My latest work is drenched in Texas, even if most of it unfolds farther north. There was no way to imagine Nathan Ray, the central character of the ensemble, without first cozying up to the Texas I knew as a boy, then conjuring a backstory where the Texas he knows is a backdrop of pain and disillusionment and gifts he cannot yet see. It's in the next book—the one with a title in flux, the one that may emerge in 2025, or maybe '26—that Texas takes a star turn, a place both abandoned and returned to. Here's a snippet: Texas was gone, falling behind us a mile a minute, and I was relieved and scared all at the same time. You leave Texas little by little and then all at once, yes, but Texas is also a magnet—a big, southerly magnet pulling at everyone else in the country with myths and manufactured romance and jobs and cheap living and low taxes. You can get away, but can you ever really leave? My answer, beyond the bounds of fiction? It's complicated. You can leave, sure. But you come back. The only thing is, I've never made a return stick. But it's early yet. I'm still upright and breathing. In the foreseeable term, of course, I'm not going anywhere. I live in Montana, I love living in Montana, and the father with whom I couldn't live in 1985 really does need me now. He lives in Montana. As long as he draws breath, and probably longer, here I'll be.

But I can't quit Texas, and unlike the answer I'd have given you twenty years ago, I don't want to. It's in my head and my heart and my memories, and the last of those is the most essential ingredient in doing this thing I do. That, I believe, is why Texas seems so insistent these days, like a song that I can't get out of my ears. It's having its say in my work, and I'm making room for it there. Perhaps, in some future I cannot yet see, I'll make other accommodations for it, too. Occasionally, either not knowing my history or not caring, a friend or acquaintance will say something cutting about the place that shaped my boyhood, and thus my life. And I'll cringe, because the cuts are easy enough to administer when Texas serves up such ridiculous stereotypes, such a bloody history, such casually cruel politics. On a day when I can find patience and indulgence for a friend's carelessness, I will say, OK, yes, but Texas is also a vast and beautiful place, full of beautiful people who contain multitudes. Texas isn't made for anyone's tidy little box. It's destined to spill out from whatever attempts to contain it. In short, it cannot be seen in simplicities when its complexities abound. 5/15/2023 1 Comment Dan GenselFriendships are funny things. Sometimes, they exist in a fixed place and time, sturdy and strong for a particular period in our lives. A counselor of mine, Jane Estelle, once told me that human relationships are often like cab rides. They have beginnings and ends. That was wise. It's true. Sometimes, though, friendships are a ride that never ends. You don't reach a station and get out of the car. You keep going, through years and locales and jobs and other relationships and seasons of your life. And sometimes they are both. They are fixed in time and endless. Those are the best friendships. Dan Gensel was that kind of friend to me. Dan Gensel is gone. I moved to Kenai, Alaska, in November of 1991. I was 21 years old, and I didn't know anybody there. I'd come from my hometown, North Richland Hills, Texas, and had taken a job as the sports editor at the Peninsula Clarion newspaper. Why? Why not? I was 21 and unencumbered. Alaska was far away. I wanted to go and could go, and that's a combination I wasn't always going to be able to put together. Now, for example. Couldn't do it. Won't do it. Want-to isn't even a factor. Years ago, I wrote a piece for the radio program Reflections West about that time in my life and the factors compelling me to move north. You can listen to it here. My first week in Alaska, I covered a Kenai Central High School-Soldotna High School girls basketball game. It featured two of the best players in the state, two of the best players in the history of the state: Stacia Rustad of Kenai and Molly Tuter of Soldotna. On one sideline was Coach Craig Jung of Kenai, a man I'd come to greatly admire in my brief time there. On the other sideline was Coach Dan Gensel. He and Craig were great friends and ardent competitors. Stacia and Kenai were coming off a state championship; Molly and Soldotna would win one a year later. I didn't know any of that. I was just a new-in-town sportswriter, trying to figure things out. The photo above, of Dan and Melissa Smith, one of the kids I covered that season, isn't from the game in question, but it's a good approximation of the Dan Gensel of my memories. After the game, which Kenai won, he sat in the bleachers with me and just talked. Where you from? How'd you come to this job? What's your background? Getting-to-know-you stuff. I liked him, right from the start. Later, I met his wife, Kathy, and his daughter, Andrea, and liked them, too. In time, it became love. But it was like, from the get-go. Those were lonely days for me, 4,000 miles from home, alone, barely scraping by, driving an on-the-verge Ford Escort and living in a one-room apartment. Dan and Kathy took me out for my 22nd birthday, just a few months later. Dan gave me seats on school buses to far-flung tournaments and let me sleep on his hotel room floor sometimes when that was the difference between my being able to cover something and not. He also gave me a basketball education, one I tucked away, then unveiled when I wrote a short story about a wunderkind basketball player and a coach and a town that loses all sense of proportion. Here's an excerpt from Somebody Has to Lose: “Mendy, it’s like this.” He squared up to the basket, squeezing the ball between his hands and planting a pivot foot. “First option: jump shot.” Into the air he went, releasing the ball at the peak of his jump and watching it backspin softly into the net. Cash, her face red, gathered the ball and rifled it back to him. “Second option: drive.” Paul took two dribbles into the lane and then fell back to his spot on the periphery. “Third option: make the next pass.” He slung the ball to Victoria Ford, directly to his left on the wing. “You know better than to just throw the ball over without even looking.” Paul turned to the players clumped on the sideline. “Shoot, drive, pass. When you get the ball in this offense, that’s the sequence. I don’t want anybody not following it, you got that?” Yes, sir,” the girls answered glumly. "You get the ball. If the defender has collapsed into the middle, you shoot the open shot. If they’re crowding you, drive around them. If you’re covered, make the next pass. This is not difficult. Run it again.” That right there, in just a few paragraphs, is the Dan Gensel philosophy of basketball. It inverts the conventional wisdom of the time—pass first, shoot later—into a kinetic, high-scoring, fun way of playing. And, man, was he ever successful. Won a lot of games. Won a state championship. Made the hall of fame. But that's not what I remember most about him. I remember that he and Kathy and Andrea became family, particularly after I came back to Alaska in 1995 for a three-plus-year stint at the Anchorage Daily News. I remember that I was a regular guest on their downstairs couch, so much so that it developed an imprint of me. I remember that they tolerated movie nights when I'd make them watch Ed Wood and Pulp Fiction, fare that was decidedly not up their alley. I remember later visits in California and Las Vegas. I remember Andrea's wedding in the early aughts down in San Diego, when Dan asked me to give the speech before the father's speech. Predictably, I went for funny and warm, extolling my love for a family and a young woman I'd watched grow up. Dan, after me, had everybody in tears with his love for his little girl. Later, in a quiet moment between us, Dan said, "I knew you'd take them one way and I'd bring them back the other." Teamwork, baby. I remember Dan's closing out the wedding reception by climbing atop a table and lip-synching "Don't Stop Believing." I hate that song, but I love that man. I remember, a few years later, Dan's serving as the best man at my first wedding. The marriage didn't last. The friendship endured. I remember all the times we talked about getting together over the past decade or so. I remember that we didn't make it happen. That'll be the only thing I regret. It's like I said: It's a friendship fixed in time and eternal. I'll carry it now, for however long I'm around. There's been a lot of that these past few years. Too much.  It's been a long while since Dan was a basketball coach. In his final years, he was a sports radio guy--a damned good one—and a grandpa, a role he made his own in an inimitable way. He and Kathy became community stalwarts in Soldotna. Andrea and her husband, Lee, are right there. It's been a good life. It will continue to be a good life, I'm sure, but those who love Dan will have to live with a big hole in it. It's a testament to the community Dan helped me build thirty-odd years ago that one of his former players, someone with whom I've been close since I was a 21-year-old green sportswriter riding a school bus, contacted me with the news. I spent just six months in that job at the Peninsula Clarion. My Facebook page is full of people I knew then and still know now, and I'm a lucky boy, indeed. Dan was 34 when I met him and 66 when he died, and that's both a long time and not nearly enough of it. I'll miss him. 1/15/2023 0 Comments Memory + Imagination = Fiction Elisa and I took our new presentation, title above, out for its first spin Saturday at the Stillwater County Library in Columbus, Montana. (Cool side note: The centerpiece pictured here was on our table at Grand Fortune, a Chinese restaurant in Columbus that we hit before the event. I can definitely say that's a career first for me. For Elisa, too.) To say that we were thrilled with the response to our program would be, perhaps, to diminish the meaning of "thrilled." We had a group of about 20 people who dug in with us, asked excellent questions and provided terrific insights, and even gamely took on a writing exercise at the end. The idea was to take The Word—the go-to warmup exercise I've written about from time to time—and apply the principles of memory harvesting to create the short fictional work that resulted. So we had the folks give us a passel of words, then we ran a random-number generator to choose one that would apply to everyone's work. That word: hayloft. Elisa and I wrote along with everyone else. I had the advantage of my laptop, so I was able to write about 630 words in the 20 minutes of the exercise. As I told everybody afterward, if the current manuscript took on words that quickly, I'd be done with it back in November. Of 2020. What follows is my effort ... HayloftMom told me I would be sorry if I didn’t go, if I didn’t see where my grandfather, her father, had grown up. I was dubious, to say the least. I liked our hotel, I liked the pool—the pool was about the only thing that made southwestern Minnesota in summer bearable to me—and I wanted to stay. She insisted that I go. I was nine. Guess who won that debate? The whole way over, our 1978 Chevy Citation baking on the blacktop, Mom told me that she’d only been here once, long, long ago, when she was a little girl, after grandpa had come back from the war in Italy. “It was like a magical place, Jeff,” she said, and I sat there thinking she should see some better magic. “Tractors. Gardens. Corn you can eat off the stalk. A hayloft, Jeff, with a tire swing. You can launch yourself clear into the rafters and come down in a soft landing.” I harumphed. Something good was on TV, and I was missing it. We made a little turn off the two-laner and went down this rutted two-track, between two fields of corn headed for silage. I wasn’t going to be eating anything off these stalks, I figured, but seeing as how I was a civilized boy, I didn’t need anything that didn’t come in a can anyway. But maybe I could slop the hogs and shovel out the chicken coop. Boy, howdy. At the end of the lane stood my grandfather, all unfolded six-foot-six of him, encased like a sausage in denim overalls and a gingham workshirt. I’d never seen him looking like that before; the guy was a navigator for Alaska Airlines, not a goat roper, but I guess it was the same nostalgia trip for him that it was for Mom, making his way to the place where he’d grown up. Beside him, another couple—that’d be great Uncle Leo and great Aunt Darlaine, I supposed, the proprietors now of the farm. I’d never met them, I didn’t think. Mom started crying once they came into view, and I shrank down in the seat, both because they were all waving stupidly at us and because Mom cried a lot that summer, and it had become clear I couldn’t do much other than let her hug my neck. We got out. Grandpa came at us, and Mom collapsed into him, crying at a stronger pitch. He folded her in like the bear of a man he was, and he reached out with a mitt and pulled me in, too. “We’ve been waiting,” he said. “I know,” Mom said, her voice muffled by his overalls. “I don’t think I remembered how far out it is.” Leo and Darlaine, having waited their turn, moved in, too. More hugs. More crying. Pinched cheeks on me, Darlaine’s doing, as she called me a beautiful boy. Torture. Sheer torture. “Jeff,” Grandpa said, holding me at an arm’s length. “What do you have to say for yourself?” “Nothing,” I said. “Well, you’ll need to do better than that.” “Mom says you’ve got corn here I can eat,” I said. “That we do.” “Where?” I asked. “Soon,” he said. “I’ll show you. What do you think of the place?” I cast a look around, for his benefit. All of them—Mom, Grandpa, Leo, Darlaine—had a look like something major would be hinging on my answer. “I’ve seen better,” I said. And then, deflation, right down the line. Grandpa gripped me by the neck, a gesture that looked loving enough but had a little pinch to it. I’d been mouthy. I knew I’d best not be mouthy again. “Well,” he said, “maybe that’s so. But someday you’ll lose a few things, and you’ll know better.” Because part of the exercise involves sharing both the memory and how the imagination was applied to it, here's closing the circle:

The memory: Hayloft was a word that led just about everybody to a farm, in one way or another. A word like that spawns more similarities, even in a large group, than a word like, say, forgettable would. I thought of the farm my grandfather grew up on, which I saw only once, when I was a little boy. I grabbed the name of his younger brother, Leo, and Leo's wife, Darlaine, because it was easier than making up new names. But Leo and Darlaine weren't the proprietors of the farm back then. (That would have been Forrest, another brother, and his wife, Margaret.) Everything else is imagination ... The imagination: Jeff's grandmother is conspicuous by her absence. My grandmother lived until 2017. Jeff's father isn't in the picture. Mine, both of mine, definitely were and are. I can't say I wasn't mouthy, or even that I don't remain mouthy, but I wasn't mouthy like that. I don't remember a hotel. Pretty sure we slept in campground barracks along with the rest of the out-of-town relatives that summer. Soon after that 1979 family reunion, we started losing people, which I'm sure is why it remains so firmly lodged in my mind. And so it goes. Really cool, unexpected, interesting things happen when I do The Word. It's why I love it so. 10/12/2022 0 Comments The Past's PresenceEven though it's been a lively few weeks, Elisa and I have been feeling the pull of something peaceful. We scuttled our anniversary plans at the beginning of the month because Spatz the Cat was ailing, then a calendar filled with wonderful things—the High Plains Book Awards for me, a new novel launch for her—conspired against just-the-two-of-us time. Today, we grabbed a little of that, heading off on a day trip to one of our favorite places anywhere, Chief Plenty Coups State Park. There, less than an hour's drive from Billings, is a place both sacred and accessible to all, a preservation of the great chief's words and artifacts and vision. Every time we go, we take a lunch, then we visit the museum, then we take the long, looping walk around his home and his orchard, basking in the quiet and the peacefulness. A visit truly is a salve. On the drive back home to Billings, just outside the town of Pryor, I stopped for one more picture. You can't see much; the gate at the property was closed and locked, and my little iPhone camera couldn't do much with the scene.

Out there, though, is a house that once belonged to a rancher named Herman Hamilton, who is long dead and even longer not the owner of the spread. And somewhere on that patch of land where the house sits once sat a tiny little trailer home, way back in the early 1960s. It was there that my mother and father lived for a short while as Dad helped Herman tend to his ranch. The time that they lived there far predates me. They've been divorced for nearly 50 years—almost the entirety of my life—and probably haven't been in each other's presence more than a dozen times in all those years. When I'm with them in the same room, it's less a case of the gang is back together and more a case of my looking at them and wondering, "How the hell did this pairing ever happen?" (Answer: Youth and beauty and mutual desire. Move on, Craig.) Anyway, this isn't about that, not so very much. It's not even about this place that sits mere miles from somewhere Elisa and I regularly go. No, this is about the adage that gets fixed to Montana sometimes when it's described as one small town with really long streets. Herman Hamilton, you see, not only was my dad's long-ago employer but also was my best friend Bob's great uncle. Bob, whom I've known only since 2013 or so. Bob, who became friends with my dad because they both owned condominiums in the same development and were chatting one day and Dad mentions Herman Hamilton and Bob says, "Holy crap ..." The world really does shrink sometimes. (Herman was also a bank robber of some repute in the 1930s, but I suppose that's another story for another time.) 9/5/2022 0 Comments Finding the Wind AgainFrom time to time, on no fixed schedule, I drop a post into Facebook that starts like this: A little [whatever day it is] craft talk, if you'll indulge me ... I then hold forth on whatever's in my head, fixating on various aspects of the writing life (structure, pacing, idea management, etc.). I'm nobody's paragon of craft discipline, that much is certain. With regard to art, I am, for better or worse, a do-it type rather than a talk-about-it type. And because I didn't come from the academy or any kind of writing program—unless you count the immersive education of journalism—I'm not really comfortable with the conversations anyway. They too quickly expose the gaps I've papered over with intuition and practice. But I do have my moments. This morning brought one of them. I talked about how an idea I got charged up about a few weeks ago stalled out on me fewer than 20,000 words in ... and how I resuscitated it. Let's go deeper ... The idea is the thing Here's how it works for me, with the acknowledgment that everything herein has a disclaimer of your mileage may vary:

The idea that recently stalled on me had a fairly quick gestation. I'd say within a couple of weeks of thinking about it a lot, I decided to start writing (having a deadline was no small factor, I'd reckon). The decision to write is the crucial one, because that locks me into a commitment I'm not quick to make (my output over the past 14 years notwithstanding). One of my favorite quotes comes from Stephen King, who likened the writing of a novel to sailing a bathtub across the ocean. The decision to start writing puts me in the bathtub, and between you and me, I'd rather be on the couch. Experience, in my, uh, experience, is a double-edged sword. Writing a novel is much harder now than it was when I wrote the first one. Harder mentally, harder emotionally, harder physically (not that I'm unloading shipping vessels here or anything, but yer boy is older than he used to be, and things like eyes and fingers and butt cheeks aren't as hardy as they once were). All of that difficulty is offset, somewhat, by a greater ability to differentiate between a garden-variety idea and one that has the legs (or sea legs, if we're to stick to the sailing metaphor) to get from here to there. The stall-outs still happen, though. Sometimes I'm able to salvage them into a short story. Sometimes they just sit forevermore, dead husks taking up space on my hard drive. So there's that. When I sit down to work, I do have more confidence now that I'll be able to cross the ocean in my bathtub than I did years earlier on other projects. I don't have a guarantee—because of how I work, which some writers call pantsing, I'm never entirely sure where I'm headed—but I have the experience of seeing these ideas through, which grants me some confidence that I'll reach the other shore. But still: Bathtub. Ocean. And sometimes the wind leaves those sails without much warning. The stalling out I discovered I was adrift at about the 17,000-word mark. On the face of it, that's not a good sign. At that point, you're barely coming out of the early part of a novel-length work into the murky middle, where you have every right to expect that you'll feel lost (particularly if you're a pantser) while you're drafting the thing. I was scared—all that work, jeopardized—but not panicked. I set my work down and I made myself quiet. Over the next couple of weeks, I considered many things:

These thoughts began competing with each other, to the point that a haze formed and settled on my head and blocked my vision. In response to that, I got quieter. I focused harder. I listened more intently to what my inner assessments were trying to tell me. And then the haze lifted. Back in the bathtub Over the past four or five days, I've revisited the manuscript in progress. I've reread every word, from number one to number 17,751. I've recast many of them. And I've come to a few conclusions:

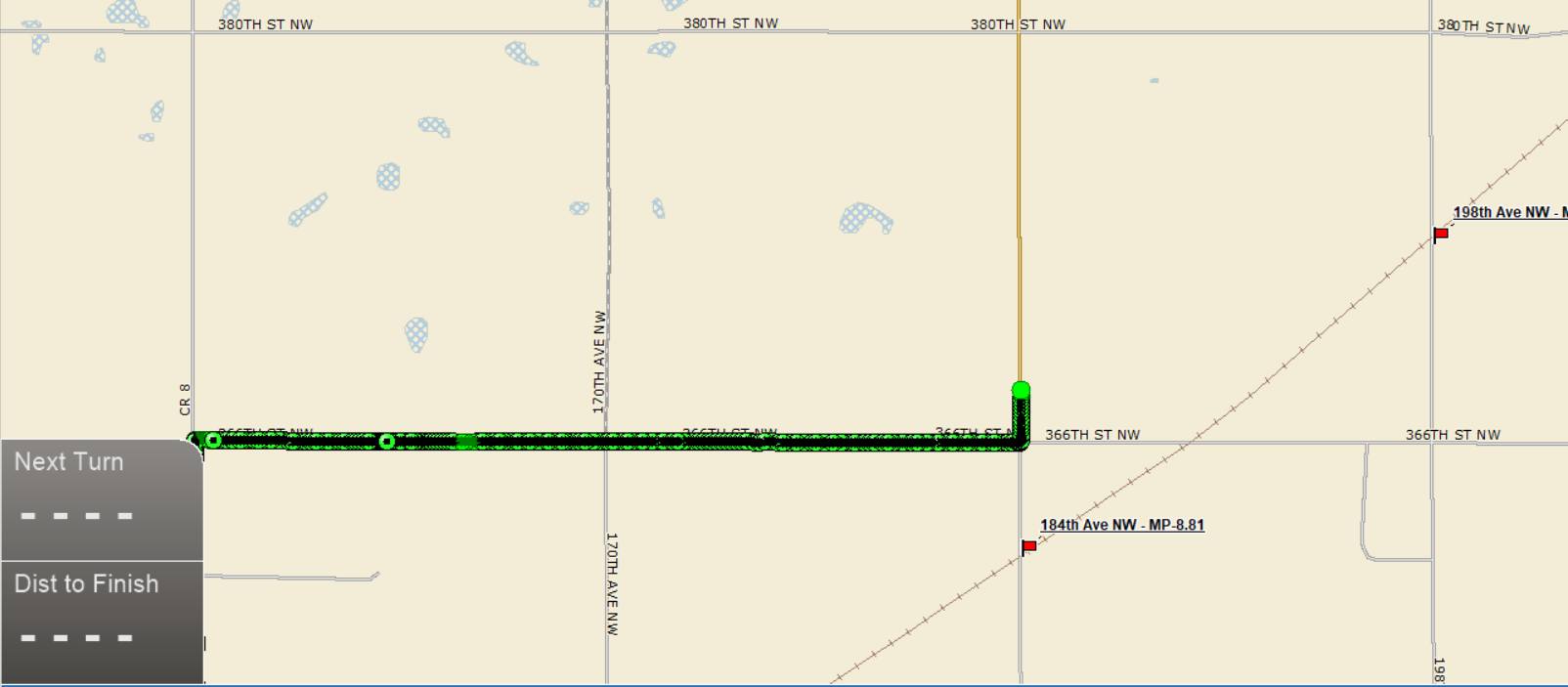

So onward we go. The sails are up. The knots are tightened. I might run the Jolly Roger up the mast, just to be a badass about it. In the meantime, there's a lot of open water ahead, but I have faith that the shore waits for me out there somewhere. 6/25/2022 2 Comments The Road Called, and We AnsweredHere we are, nearly halfway through 2022, and I've only just caught up to reconciling something that happened in late 2021. (I suspect this is either because I'm slow on the uptake or because I just hadn't taken the time to lean into my feelings and sort them out. Maybe even both!) At any rate, at the end of the year, the company for which I'd done some occasional pipeline inspection work for the past several years folded up its U.S. operations. Just like that, I was out of a gig. First, the important stuff: It wasn't more than a trickle of an income stream, so it's not like I was jobless or under the threat of imminent financial disaster. It wasn't and never had been a career, so I wasn't grappling with the loss of self. The point being, it wasn't a massive blow to the bottom line or self-identity. And yet ... It was a blow, undeniably. I felt the absence, and I felt a little unmoored by the fact that I didn't have any work trips coming up. I found myself thinking inordinately about the places I would commonly go on these work trips—Buffalo, N.Y., and Chelsea, Mich., and Michigan's Upper Peninsula, and the far reaches of Minnesota and Wisconsin. My thoughts would drift to Minot, N.D., where I'd gone for my first such job, way back in 2015. And then it occurred to me: What I'm really missing here is that liberating sense of being gone. I'm 52 years old, and I've never lost that urge toward motion, travel, getting in the car and going, any direction will do. I like hotels and corner restaurants. I like people watching in places where I don't know anyone. I like seeing what's over the next horizon, even if I've seen it before. By now, I surely most know that it's incurable. So I told my understanding wife that I needed to go, and I packed up the dog and a week's worth of clothes, and I went. The idea was to go to Minot and, from there, launch revisits of a few pipeline routes that emanate from there. The Minot part was easy enough. The rest, though, went against my expectations. Here's a glimpse (material stolen from a subsequent Facebook post):  See the orange post there? I tracked my first pipeline tool from that site (smack in Berthold, N.D.) back in 2015. See the orange post there? I tracked my first pipeline tool from that site (smack in Berthold, N.D.) back in 2015. I haven't missed the pipeline work—which, you know, is work—nearly as much as I've missed the travel and the solitude. The solitude most of all. I don't think happiness exists in a fixed place; it is, instead, what you make of it and where. But if I'm wrong about that and happiness really is out there in a place you can pin on a map, then I'm fairly certain that place is on a tertiary road in some lonely precinct where no one goes on vacation. I came here thinking I'd ride the full length of a few lines, stopping at every checkpoint and taking them in, and I was wrong about that. I don't need that much immersion. I just needed to be out. Away. Gone. Just for a few hours at a time. God, how I loved it. God, how I've missed it. On our last full day in North Dakota, Fretless and I rode a small portion of an 85-mile line that runs northwest from Berthold, N.D., to the Canadian border. It was, simultaneously, a total kick of nostalgia and an entirely new experience. The only time I did this line for real occurred in the deepest of winter, 2017. It was bitterly cold that night. The snow was in drifts. The wind blew the snow around in ways that would mess with your perception of things. On those dirt roads, some of them just two-track, you'd see a pile of snow and you'd stop the car and get out, the wind biting your face, and you'd walk it first to make sure you wouldn't get stuck. You don't want to get stuck, believe me. It's happened to me, more than once. It's bad. I once waited for seven hours in Wisconsin, my work vehicle sunk to its axles in a blizzard, for a tractor to come and yank me out. You don't want this. See the pipeline marker in the photo above. To do my job, I'd have to wade through snow, sometimes chest-deep, and put my sensory equipment there to record the tool passing by, deep underground. Then, after a passage, I'd have to wade back out and get the equipment, then try to swim back to the vehicle, hoping I didn't get hung up alone out there. Meanwhile, the tool was zipping along to the next checkpoint at about 7 mph, which is really hauling ass. It was desolately lonely and dark and cold and scary. I loved it so much. The line parallels railroad tracks (see the map above), which cross the road at uncontrolled intersections. In the night and the cold and the dark, snow flying sideways and obscuring your vision, you'd have to be careful, hanging out in those places. When Fretless and I went out, though, it was different. Warm and clear. Sunny. No snow. No drifts. More red-winged blackbirds than I could count, although not one of them stood still long enough for me to get a picture. Farmland was verdant with moisture, not gray and white and foreboding like in my memories. That night I ran the line for real, in March 2017, we finished at the border and the snow was coming down in massive clumps. I drove to my waiting hotel in Williston, more than 100 miles away, unable to see a damn thing, holding my phone in front of me and using the GPS program to keep my truck on the road, or where the road was supposed to be. I didn't tell my wife about that until a day later, when I was safely home. I don't miss that kind of stuff. A little more than a week ago, when I'd had enough, I asked Fretless, in the backseat, if he wanted to go back to the hotel. He wagged his tail agreeably. I cracked the windows, letting in some fresh air, and we got the hell out of there. It was glorious. Every little bit of it. I had to work the evening of getaway day, and long gone are the days when I can drive for eight hours and work for another eight, so we stayed that night in Sidney, Montana, another dot on the map rich with memories. Again, borrowing from Facebook:  See the windbreak there? That's on the southern edge of Fairview, Montana, a little town that straddles the Montana-North Dakota line. In late summer 1981, when my dad was in the midst of moving his drilling rig from one town to another, the right-front tire on his International Harvester Paystar 5000 blew out and he, with much effort, brought it to a stop right there. I have a clear memory of this because I was in the passenger seat, so it was my side of the truck that dipped precipitously, as if we were going to pitch over on our side. I also well remember it because it was a classic bad news-good news scenario. Bad for obvious reasons, and for these reasons: Dad's hired hands, who'd ordinarily be following him, had gone out ahead of us by a couple of hours. We were alone. Good because there's a house right there, and a small town just ahead. Easy to make a call, even in 1981, and get some help dispatched. Now, lemme ask you this: What do you suppose the percentage chance was that this boy, who lived at the time in Texas, 26 years later would marry a woman from tiny Fairview (population now 900, but much smaller then)? As it turned out, 100 percent. (We divorced seven years later, so it's less a fairy tale than an interesting coincidence. But still.) OK, let's move a dozen miles down the road to Sidney. That train engine, in Veterans Memorial Park, with Fretless offered for scale? I climbed all over that thing that summer. I was 11 years old, and that's pretty much the recreation that was available to me. The city fathers hadn't yet fenced it off, so I was free to clamber wherever I could get to. I also chewed illicit tobacco, given to me by my dad's helpers, who encouraged me to have all I wanted, knowing full well what would happen to me. Bastards. Anyway. Across the street, still standing but no longer operational, it seems, was the Park Place Motel. I lived that summer in one of the bottom-floor rooms, with dad and his wife. It was entirely too cozy, entirely too stifling, entirely too familiar. And yet, I'm thankful for the memories, which quite without my realizing it were becoming fodder and fuel. I've set stories in that park, and in those fields beyond it. With very little disguise (or even much of a name change), I've turned Fairview into a character all its own, the little town of Grandview in This Is What I Want.

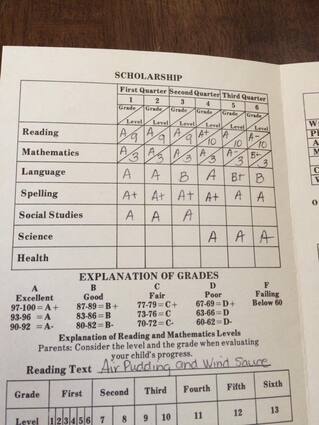

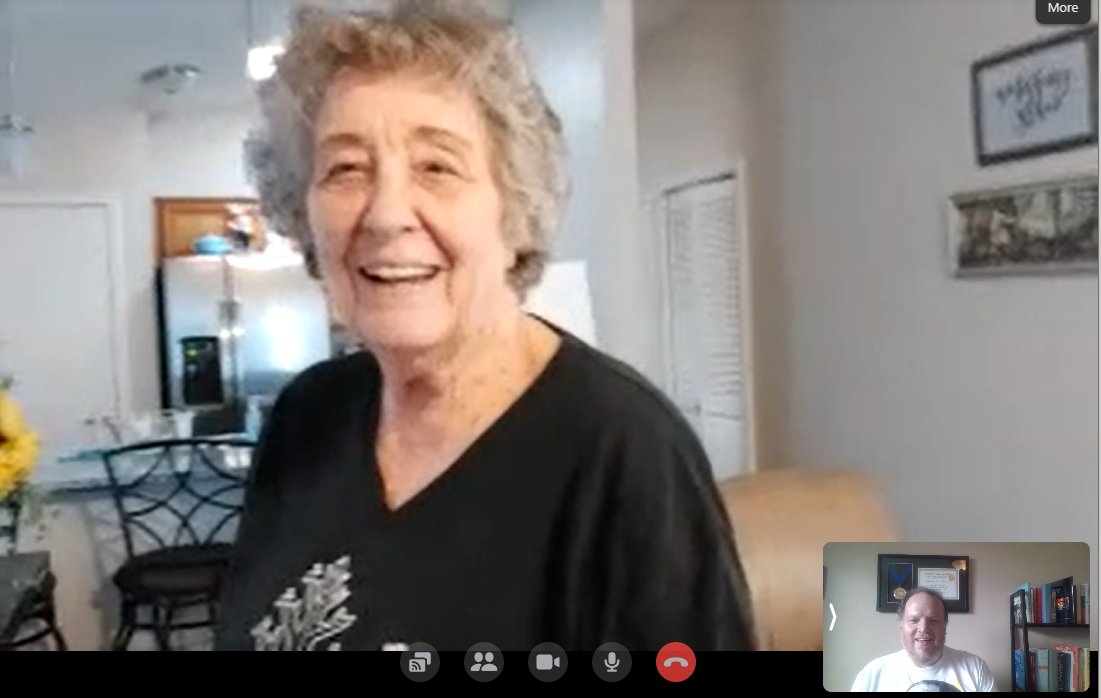

It's all been a gift, every bit of it. I'm grateful, all the time. And I can't wait for the next trip ... 5/25/2022 0 Comments Some Who Shaped Me That's not a chair for reading, son. That's not a chair for reading, son. Today's little trip through the memory banks requires us to visit late summer 1978, a suburb of Fort Worth, Texas, called North Richland Hills, a neighborhood (and its elementary school) called Smithfield. Smithfield, in fact, was what most folks who lived there called the place back then. North Richland Hills, now a sprawling burg of about 70,000 people, was a relatively new concern in those days, having been voted into its own municipality 25 years earlier when Richland Hills, the now much smaller adjacent community, declined to annex the area. By 1960, North Richland Hills had gobbled Smithfield, a freestanding community to its north. The census in 1970 put North Richland Hills' population at just a shade more than 16,000 people. We were 30,000 strong by 1980, so you can sort of suss out the math for '78. We were getting bigger britches, for sure, but we were a cozy group. If you were to cleave off the people who thought of Smithfield as Smithfield, because that's what it had always been to them, you'd be left with an even smaller subset. Anyway, it was a different time and, in its way, a different place from what it is now. I was a different boy. There at the left, that's a pretty good approximation of what I'd have looked like (minus the wicker chair) as I pedaled off on a summer day to our neighborhood school, Smithfield Elementary, to see if the classroom assignments for the coming school year had been posted. When I saw that I had been assigned to Charlotte Cooke's classroom, I know I was overjoyed, for that's the teacher I'd been hoping to get as I moved on from second grade to third. So here's the thing: I didn't spend long in Mrs. Cooke's class. Maybe a week. Maybe less. I don't remember, exactly. What I do remember is that a new third-grade teacher started at Smithfield that year, a newly minted graduate who had been a late hire and was getting her first classroom at our school. As I recall, a class was built for her first by asking for volunteers to shift over from their assigned teacher to this new one. After that, the administration would do it by conscription. Again, here's where the finer details are lost to me in the intervening 44—holy shit, 44!—years, but I do remember that I volunteered. I do remember being concerned that if kids didn't act like they wanted to be part of this new teacher's class, she would get discouraged and think she was unwanted. I am certain—utterly certain—that given my affection for Mrs. Cooke, volunteering wasn't what I wanted. I felt like I needed to do it. Where such a notion came from, I have no idea.  I've made a lot of stupid decisions in my life. Made a lot of fortuitous ones, too, and volunteering for Donna Spurgeon's third-grade class in 1978-79 is a standout in the latter group. I loved her almost from the get-go—I do recall some initial cold feet about leaving Mrs. Cooke's class that my mother told me I'd have to overcome, having made a commitment—and I've loved her straight through. She later had my sister (twice, I think, after she moved up to a fifth-grade classroom), she changed schools and I kept up with her, I visited her classes a few times through the years, I was able to wish her a "well done!" when her retirement came through, and we keep the conversation going on Facebook even today. Back then, in 1978-79, I ended up feeling like I got the best outcome possible. Mrs. Cooke still figured into things, teaching me the perilous math of third grade (fractions!) and breaking me of the annoying habit of making my fours look like nines. But Donna was an all-timer, the kind of teacher I made it a point to keep up with as the seasons changed, for both of us. She started as a teacher (and even raked me pretty hard on my language skills, as evidenced by the report card above), then ended up as a friend. Doesn't get any better than that. So what of Mrs. Cooke. Well ... Sadly, I didn't keep up with her. I liked her, appreciated her, enjoyed her instruction, but time went on and so did I. And so did she. But let's go back to this idea of Smithfield as a place in time and as a heart's memory, just for a second ... There's a dedicated group of people who are from where I'm from, who've stayed, who haven't let the idea of Smithfield get too far away even as its time as a stand-alone town recedes. Every year, first weekend in May, there's a reunion. Living several hundred miles away, as I do and as I have for most of the past 35 years, I've never been to it. That's my failing. This year, I sent a stack of books to be included in a raffle, to hopefully play some small part in keeping these annual get-togethers going. A few days after the event, I got a text message from one of the organizers. She said someone had dropped by, seen the books with my name on them, and remembered me. Charlotte, she wrote. She was Charlotte Cooke, and she's Charlotte Williams now. Well, I'll be damned. A torrent of memory came on. You can see it, in every paragraph above. The organizer, LaDonna Powell, and I launched a conspiracy. We'd send her a book. I'd enclose a card. We'd spring a video chat on her. We'd close this circle that's been hanging open since Jimmy Carter was president. There she is, and there I am, all smiles for our long trip back to each other. I'd like to say I would have known her on sight, on the street, but I probably wouldn't have, and I'm certain she wouldn't have known me. But as we talked—just briefly—I could see the flickers of kindness and care that made her such a wonderful teacher for all those years, one whose classroom I badly wanted to be in when I was 8 years old and rode my bicycle down to the school to see if the luck of the draw had been with me. It had been, and yet I asked to be reassigned, which turned out to be only one of the most consequential decisions of my growing-up years.

Sometimes, it all works out. What I said to Mrs. Williams, in our chat and in the card I included with her book, is between the two of us. In the broad strokes of it, I can say only that I'm grateful. For the kindness of the teachers I've known, whether chosen by me or for me. For the intercession of LaDonna. For the chance to say thank you, and to mean it. Thank you. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed