|

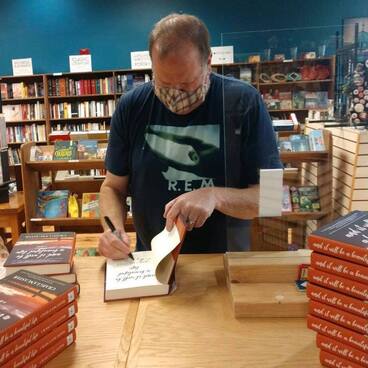

4/18/2022 0 Comments Who I Am. What I Do.**—If I'm doing it right, there's both overlap and freestanding territory. For years and years, I didn't do it right. Facebook, I've noted before, isn't good for much, but it's damn near essential for a few things: easy keeping up with far-flung friends and relatives, recipes, irritating others with your daily Wordle grid, cat memes, birthday greetings (the most heartwarming day of the year, every year), etc. Increasingly, I'm finding value in the stored-up daily memories, especially the things I don't remember writing or don't remember the impetus for writing. Today (April 18) served up this kick to the hippocampus: My newspaper career started in October 1988, when Jim Fuquay gave me a job as a part-time correspondent at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. It ended in August 2013, when I left my job as night city editor at the Billings Gazette. In between, I worked at nine newspapers in six states. Some jobs I took for the adventure (Peninsula Clarion, Kenai, Alaska, age 21). Some I took for money (Dayton Daily News, 1994). I almost always regretted those, by the way. Some I took for escape (Anchorage Daily News, 1995, to get away from Dayton). Some I took because I knew they'd make me better (San Jose Mercury News, 1998). One I took to correct a mistake (San Jose Mercury News, 2000, after bouncing to both San Antonio and Olympia, Wash., earlier that year). Twice I accepted jobs and then backed out before I was due to report (particular apologies to the Lewiston (Maine) Sun Journal). I took different jobs for different reasons. Sometimes those reasons panned out and sometimes they didn't. But most of the time, what I was really looking for in a new job was some new version of me. I never found that. Not once. It feels good to finally admit this. Let's unpack this, shall we? Elisa and I were talking about this the other day, having reached an age at which there's plenty in the rearview to examine and second-guess and (we hope) plenty of road ahead to consider other pathways: If we had it to do again, would we make different career choices? What might we have done instead? Because those ponderings inevitably run up against the butterfly effect, we ended up in a predictable place: Nope. We're good. But it remains an interesting thought experiment, if only for the clarity you find about the choices you did make. I ran toward print journalism—and stayed there a good long time—because it made good use of my particular talents and because it was, in my narrow sense of the word, a daily adventure. Within the strictures of daily newspaper production—you have to gather the stories and stats and pictures, you have to edit the material, you have to design the pages upon which it all rests—were wide variables in what you dealt with daily. The news was always different. The pages began, every day, as blank canvases. I loved that. What I traded for that was significant, though: Friends in other lines of work made more money, enjoyed greater security and stability, had evenings and weekends free, etc. These are not insignificant things. Who I was and my stance with regard to work, especially in my 20s, are so entirely removed from who I am now that I have to strain to remember that guy. I know that his entire definition of self was wound up in being a journalist, that he went to bed thinking about it and woke up each morning with it on his mind, that he bounced up to the world with that shingle around his neck. I lived to work, and I sought out any chance I had to work extra hours, to get plum assignments, to make myself as close to indispensable as I could (an illusion, of course, but one I willingly bought in those years). It's what I didn't do that taunts me now. I didn't fall in love in those years; how could I, when the aggrandizement of Craig the Journalist was front and center among my priorities? I get at that idea in the Facebook memory above: In all my wandering around, looking for some new version of me, I carried my old self into each new situation (wherever you go, there you are). I didn't learn to play the guitar or take a judo class or write a novel. Until, you know, I wrote a novel. When I was trying to emerge from brokenness and impending divorce in 2014-15, I spent a lot of time with a counselor (highly recommended) and with my nose in reading material aimed at my mental/emotional state (e.g., King Warrior Magician Lover) and my soul (The Rag and Bone Shop of the Heart). I wanted to understand what was happening to me, why it had happened, the parts for which I had responsibility (many) and the parts I had to let go (also many). I also read a lot of shorter pieces, some with resonance and some without. Two that stick out, years after the fact, were written by Mark Manson. I recommend these highly, whatever your situation: Fuck Yes or No: "Since you’re now freeing up so much time and energy from people you’re not that into, and people who are not that into you, you now find yourself perpetually in interactions where people’s intentions are clear and enthusiastic. Sweet!" The Guide to Strong Relationship Boundaries: "People with poor boundaries typically come in two flavors: those who take too much responsibility for the emotions/actions of others and those who expect others to take too much responsibility for their own emotions/actions." I hear what you're saying. Craig, you're saying, this is great, but you're talking about personal relationships now, and you were talking about work, and I'm confused. No, no, I'm still talking about work. This is the point. In the extreme emotional duress of a divorce—a traumatic thing I do not recommend, unless, of course, it's the thing that will skirt an even bigger trauma—and with the help of a well-trained, compassionate human and the collected wisdom of learned thinkers, I began to unlock some problems I'd dragged into every area of my life: my interpersonal relationships and my relationship with work. This hard process of dredging up changed me. Better personal boundaries also meant better work boundaries. I'm no less good at what I do—in fact, I'd argue that I'm much, much better than I've ever been—but no longer am I defined entirely by a magazine spread that I've designed, or a report I've edited, or a chapter I've written. What I do is also who I am, but it's not the entirety of the picture. It was written mostly as a joke, but like any good joke, there's truth inside it. In the sidebar on this blog, I define myself this way: Craig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. I can live with that.  Signing copies at This House of Books in Billings. Signing copies at This House of Books in Billings. In some significant ways, what's happening now in the American workforce—this thing they're calling the Great Resignation—is a manifestation of an assertion of boundaries. We've been through a lot: social tumult, a deadly pandemic, a rebalancing and cross-pollination of work lives and home lives. People are reconsidering what they value, how they want to toil, whom they want to toil for, and what price they're willing to accept for those vast swaths of their finite lives. Good. It's healthy in the long run, even if it's upsetting to the status quo in the shorter term. The last time I moved—packed up my life and my car and my expectations--for a job was more than 20 years ago, when I left Olympia, Wash., to return to San Jose, a place I never should have left in the first place. I can't imagine doing it again, although one of the benefits of growing older is learning that one really shouldn't say never. My point is that although I plan to strap on the work boots for a good long time—I like to work, a fact that was clear even 30 years ago, if badly applied--where I am and who I am and how I'll share those parts of me need more than just a job. I need a multidimensional identity, too, and at last I have one. That's what I was missing in all those moves cited in the Facebook post above. The last time I recast how I define myself professionally occurred when I wrote and published that first book and I figured I could finally call myself a novelist instead of just a guy who wished he had one inside him that he could extract. That was nice, too, but it's not everything. Without the laying about and eating breakfast and doting on my nieces and nephews and being a son and a brother and worrying about the Dallas Mavericks and spinning through this life with my wife, in fact, it wouldn't mean much at all.

0 Comments

3/30/2022 0 Comments EmergingLike many people, I've come to loathe Facebook in as many ways as I find it an indispensable means of keeping up with close friends and loved ones. Perhaps it's the indispensability that I loathe most. I also post things there deliberately, knowing that I'll be shown them again, year after year, so I can remember certain days with some degree of precision. Two years ago, March 30 was just such an occasion. On this day in 2020, the moving trucks showed up at our house in Boothbay, Maine, and whisked away our stuff. By then, it wasn't even our house anymore; we had closed on its sale a few days earlier and were just extremely short-term renters. We loved that house. We liked Maine. But neither love nor like was enough to hold us. That's old ground that needn't be gone over again. What's hard to remember now, even two short years later, is just how frightening the whole thing was. The world had closed up. We had moving guys tromping through the house, and we—Elisa, me, the dog, the cat, my dad, his dog—kept our distance and hoped they weren't sick. Hoped we weren't sick. Wouldn't be entirely sure how to know if we were or they were. There was a lot of taking things on faith. There was a lot of handwashing and surface disinfecting. There was a lot of uncertainty about what awaited us on the road. That first night, we stayed at a hotel in Portland. I, wearing rubber gloves and a paper mask, fetched dinner for everyone and brought it back to the two rooms (guys and dogs in one, woman and cat in another). Same drill for the subsequent nights, in Buffalo and Chicago and Minneapolis and Bismarck. We limited our points of contact. I did all the gassing up for the two cars, which were similarly subdivided with occupants. I wrangled all the meals, meeting Doordash and Uber Eats in hotel lobbies. In the East, where the pandemic initially hit hardest, we stared in wonder at empty turnpikes and rest stops. The farther west we drove, the more lax people seemed about what was happening. In Janesville, Wisconsin, I turned on my heel and left a store after seeing scores of unmasked people there. In North Dakota, a convenience store clerk poked fun at my mask. In Ohio, I asked a guy to move down a urinal, and he reacted with anger: "I'm not sick." "Fine," I said, "but maybe I am." When we got to Billings, it was more of the same. We were diligent, about our hands and our faces and our surfaces. We were scared. We sequestered ourselves away for two weeks and hoped we wouldn't get sick. The unknown was a menace. We weren't alone in feeling that. It's two years hence. We're just back from a two-week vacation. We saw loved ones. We hugged old friends. We gathered with thousands in a sports arena in downtown Dallas. We crowded into a banquet hall and said goodbye to a friend. The pandemic remains with us, of course, but it's different now, too. We're vaxxed and boosted, and soon to be boosted again. In recent weeks, we've begun stepping out again. Our first sitdown meal in a restaurant happened a few weeks before we traveled to Texas. Our first evenings out to see plays (masked), too. We carry the vax cards and the masks, in case they're needed. I imagine I'll wear one forevermore in airplanes and on trains and in crowded supermarkets. I'm cool with that. It's not a burden. We've been through two flu seasons now without the flu, a first for either of us. Credit the masks. Our doctor surely does. And yet, with the specter of omicron and whatever new variants might emerge, we worry about a scratchy throat or some mild congestion. Just the other day, we broke out a test for Elisa, who was feeling a little poorly. Negative. We've been lucky. No doubt about that. But we've also been diligent. We'll try to stay so, even as we dip further into what used to be normal life. The point of all this? There is no point, really. Gratitude. Caution.

We've had a hard two years, all of us. We've lost people we shouldn't have lost. We've grown isolated and angry. We've missed things we shouldn't have missed. May we find grace. May we offer it, too. 3/23/2022 0 Comments We Who Loved JonElisa and I are just back from a two-week vacation, one spent doing all the things one should do when granted such a release from ordinary life. We saw our favorite basketball team (a loss, but whatever), we ate good food, we hugged loved ones and old friends, and we explored a bit of the Texas coast. A damn good time. And then, to finish it off, we headed to Santa Fe and said goodbye to Jon Ehret. Somehow, the world has kept on spinning since he left us on Aug. 21, 2021. He's often on my mind, always in my heart, and badly missed by everyone who grew to love him. On a late-March day in New Mexico, we raised a toast. It was beautiful. He was beautiful. And it made me wish, again, that he could have been at the table with us, noshing on good food and reveling in good memories. I met Jon when I was 20 years old. I lost him when I was 51. We packed a lot into those 30-plus years. Just not enough. It would have never been enough. Saying goodbye, though painful, was a gift. His celebration of life brought out two men I knew at a crucial point—at the same point, roughly, that I met Jon—when I was a youngster who needed some direction and role models in a career I'd chosen but didn't quite know how to get myself into. In 1990 and 1991, I was working as an agate* clerk in the sports department of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Jon, just out of grad school, was an editor on the sports desk, particularly gifted at page design, the discipline I fancied for myself and yet had never really done**. Frank Christlieb was a copy editor on that desk. Steve Waggoner was a copy editor and layout man. All three of them were heroes to me, along with an entire crew I can still mostly name, all these years later. Hille and Ed and Darrell and Dano and Doug (RIP) and Bullet and Sven and Lisa and Susan and Joe Mac and Joe and Coach and Tod (also RIP) and Brian (yet another RIP) and even my stepfather, Charles Clines, though we never made much of our connection while at work; we were too circumspect for that. So, there I am, Saturday afternoon, waiting outside the venue where we're to say our goodbyes to Jon (dammit, I still cannot believe it), and Frank is the first one I see. It's been upward of 30 years since we've lain eyes on each other, but thanks to social media, it's instant recognition and a hug. Waggoner comes, too, and it's the same thing. Thirty years gone, but time, for a few moments anyway, has stood still and let us greet each other. Ana, his wife, same thing. She was there all those years ago at the Star-Telegram, and she was there Saturday, and it was nothing short of wonderful to see all of them. And it was the next day, on the first leg of a two-session drive home to Montana, that I realized how Jon had blessed me with another gift. I got to hang out with those folks, to hear their stories and to tell mine, and maybe to impart in some way how much I was affected by being around them when I was a little pissant editorial scrub. Not because they condescended to me (they did not) or because they were especially nurturing (they sometimes were, but they had jobs to do that didn't involve nursing me along), but because they provided an example: Here's how the work is done, here's how you take it seriously, here's the difference between being diligent and being lazy, and here's what it looks like when you've done well. I carried that stuff with me to other states and other newspapers and other jobs***, right up until 2013, when I left the print business. I hucked those lessons onto my shoulders when I resumed my career as a journalist****. I was lucky, indeed, to have such role models at such an age. And we were all lucky to have a friend like Jon. As for the celebration of life itself, it was bittersweet, as such things tend to be. Jon was well loved by many, and they came out to toast him. Elisa has a really nice remembrance of him at her blog. You should read that. I gave one of the eulogies, which I'll mostly leave to the air that carried it, but there's one part, at the end, that I need to remember for the next loss that takes me to my knees. You live long enough, and they come:

I could rage against the fates that took him so young—when he had a son to see deeper into life, and a wife who loves him so and with whom he made common cause, and birds to tend to, and veterans to honor, and talents yet to be mined and developed, and chicken wings yet to debone. And yet, I don’t. I’m not angry at the universe for calling him back to stardust, no matter how unfair the timing might seem. How could I be angry, when it’s the universe that gave him to us in the first place? He is my brother. He has been that since the first day he and I looked at each other and mutually acknowledged, yeah, OK, I’ll take a few spins with this wacky bastard. That was our call, our decision, and the vagaries of life and loss have no say in it. Jon's still here. He's not accessible in the way that I would prefer, but he's with us. And we are with him. Always. End notes * — Agate, dears, is the small type you see in newspaper box scores and the like. At a major metro paper like the Star-Telegram in the early '90s, it was a full-time job to compile agate, set it, take call-ins over the phone, make a dinner run for the editors, etc. ** — I ended up winning some nice page design awards in my newspaper career, and I've done the design work on an esteemed quarterly magazine for nine years now. It's nice when aspiration meets opportunity. *** — I went into all that in a Substack post. **** — See this. 1/24/2022 0 Comments My BoyLet me tell you a little something about this boy … As of tomorrow, January 25, he’ll be 3 years old. And because I’m nearly 52 and have learned how fast time seems to go, I have to check myself sometimes against pre-emptively mourning what will happen if the actuarial tables are true for both of us: I’ll have to say goodbye to him and let him go. Most of the time, I can get my head straight, tell myself to enjoy the time I have with him, but sometimes I get fixated not on the past, as is my wont, but on the future. This is one of those times, because he’s hit this milestone. Contrary to the old saying, he's not my best friend. That is and always will be my wife, as she should be. But he’s my best buddy. I’ve lived to an age—and lived through a pandemic, so far—that has calcified my lack of interest in spending great scads of my time with other people. I’d rather stick to my house and my patterns and our tight little circle here, two people and a cat and a dog. I say again: He is my best buddy. He goes where I go. He hears my thoughts. I check in with him, and he checks in with me. We move around each other like an old married couple, which we're not, but it speaks to the familiarity. So, anyway, three years ago … It was Jan. 27, 2019, and Elisa and I were about to step into a movie theater in Brunswick, Maine. Before we did, I checked my email via phone. I had a message from Doxy Den in Mechanic Falls, a breeder (I know, I know—I wanted a dachshund, and this is not a mill; it's a family that loves their dogs): “The puppies arrived on Friday! We had 5 boys! I have 3 black/tan long hair males available! There are pictures up on our Facebook page. Groot, Drax and Rocket are the puppies that are available. Rocket is tiny but strong and doing well. Groot has a little bit of white on his chin and the tips of his toes.” I went to the Doxy Den Facebook page, looked at the pups, and made my choice: I’d take Groot (but not the name). Over the weeks that followed, I watched him grow, from a distance. Because I had a trip back to Montana planned for March, I didn’t pick him up until April 9. He was the last of the five boys to go to his permanent home. The Doxy Den owner’s granddaughter cried because she had to give him up. I cried when I got him to the car on a wintry day, for the long drive home. I'd been waiting on him, and he was finally with me. He spent the better part of an hour and a half trying to crawl from his bed into my lap while I tried to drive. Finally, late in the trip home, he hit the wall (see below). I’ve had many dachshunds, and I’ve loved them all. Just get me going on Sniffer and Mitzi and Zula and Bodie. I loved them equally, but they came to me at different times in my life, and thus their impacts have been different. Fretless’ importance to me has, perhaps, been a little outsized. My world has gotten smaller these past three years. He’s filling more of it than he might have in another time.

Fretless came to me at a time when we lived in a beautiful place that didn’t feel much like home, and we were still struggling with what to do about that. Fretless and I, almost immediately, began taking long walks in the woods, and he helped me make my peace with Maine. In hindsight, I can see how much I needed that. Long may he be with me. We're not near done yet. 9/24/2021 5 Comments Back to the Fork in the RoadIt's Sunday, September 19, and I'm on Interstate 25 in Casper, the nose of my car pointed north, toward home, a few hours away. I'm tired. My dog, Fretless, lies languidly in the passenger seat. He's had enough after a week away. So have I. Home, my wife, the cat—they all await. We have plenty of gas, had a bite to eat back in Douglas, fifty miles behind us. We have everything we need. The smart play is to get beyond this oil town and open up the cruise control a bit, see what this Toyota can do as we zip back into the emptiness of Wyoming and, eventually, get pulled into the embrace of Montana. So, of course, I exit the interstate, pick my way through downtown Casper, find CY Avenue—I once called it, in a novel, "the spine of the Casper grid system," which may or may not be true—and follow its familiar path to where I turn off for Mills, a little town north of Casper, and as I do, the well-trod memories come at me again. What I've come to see has been seen before, many times, and is likely to be seen many times yet, and if this particular side trip is taken as evidence that my life is in reruns, I will say only this in disputing that notion: Context is important, in all things and especially in this: I find it instructive, or at least perspective-granting, to be reminded of the life I might have had so I can better appreciate the one I'm swimming through. It's Friday, September 24, the day I'm writing this, and I'm reflecting on a spontaneous turn in a phone conversation with my mother this morning as we talked about other things. We talked, quite organically, about a decision she made for both of us in 1973, my third year. I was a capable kid, even at that age, blessed with an ability to carry on conversations with adults, but this matter was beyond my perception. She didn't want to live in Mills, Wyoming, anymore. That was surely half of it. The other half was that she didn't want me to live in Mills, Wyoming, anymore. She looked at the present, our life with my father there and what it seemingly held for us, and she projected out her future and mine and didn't like where those lives seemed likely to end up, and she did something about it. She took us out of there, into life with a man she'd met that year, the brother of her best friend, a man who lived in Euless, Texas. Not that it's anyone's business, but they hadn't had an affair. They'd had a connection, a chance meeting at a party that turned into a deep conversation that blossomed into a friendship and has become a nearly 48-year marriage. We talked about it this morning, Mom and I, this decision that with each passing year strikes me as more and more brave, more and more essential to both of us (and now to so many others—generations of others), more and more the line of demarcation, in strictly selfish terms for me, between where my life was pointed and where it ended up. I can see now, when I'm more than two decades older than she was then, how much gumption it required for her to do what she did. She was alone there, much of the time. She was 28 years old, and while Dad might not have represented maturity or loving or grace (I love the man, but let's be honest about the limitations), our prospects there were much more certain than they were anywhere else. There was a home well on its way to being paid off, an ascendant business, money in the bank. It would have been all too easy to stay. Many people have stayed for less. Mom saw the future and she left. I'll never receive a finer gift. So, you see, Mills, Wyoming, is actually a bit player in this what-might-have-been contemplation. It wasn't Mills we were escaping so much as who was there and what our life was there. It could have happened in Moline or Schenectady or Topeka. Could have, but didn't. This is, at its heart, a human story, a story of a boy with three parents who've imprinted him in wildly varying ways. I love my father, a love that shines through my struggles to understand him and his to understand me. It's a love strong enough to withstand my suspicion that my start in life would have been less than it was had I finished my growing-up years in his house. The math of that situation is inconceivable to me, given the way it all went. It would have been Mom and me in some kind of alignment agaInst the gravity of the way he is, the work that was always taking him away from us, and the instability of the home we were living in. I'm certain Mom's decision all those years ago hurt him. I'm also certain, if Dad can access clarity and honesty, that he'd say it needed to happen. For all of us. And what can a boy like me say about his mother that hasn't been said in better ways by better thinkers? She is pure love when it comes to her children and her children's children, but to leave it at that misses the fullness of who she is. At an age that seems to me, now, to be impossibly young, she was relentlessly wise. She had aspirations for herself (and has them still). To my ongoing gratitude, she could see a time coming when her son would have them, too. In so doing, she brought me into the sphere of the man who became my stepfather. Back then, he was a 31-year-old sportswriter at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, a man who had his own broken first marriage, a son, and regrets. He also had a shared hope with Mom that they could make a go of it together. I can scarcely remember a time before his presence in my life, and he has never, not once, treated me as anything but his own. That has made all the difference. I go back to Mills to remind myself that it could all have gone another way. Could have, but didn't. So what do I make of Mills, all these years later?

I think it would be presumptuous of me to make anything of it beyond my sliver of experience there. It's steeped in nostalgia and memories and wonder. Its presence on the outskirts of my life has been a professional gift, surely (the old memory + imagination thing), as well as fodder for the occasional facile joke. (One could certainly quip about "welcome to Mills, please set your watch back 20 years" or wax irreverent about how hard the wind blows there.) The thing is, I've lived enough places and known enough people to realize something important: Most anyplace can be home, depending on who's doing the inhabiting and what they bring to it. I suspect—but don't know for certain—that my life would have harder and less interesting had I grown up in Mills. It's the not knowing, of course, that makes it such a delicious ponderable. So I go back, and I look around, and I try to imagine who that boy might have been, what kind of man he might have become, where he might have gone and what he might have seen. And because Mom imagined something else entirely, way back in 1973, I can be ever grateful for the real story that lies alongside the conjecture. 8/23/2021 15 Comments Jon Ehret, My BrotherNot that we’re back in eighth grade or anything, but in the couple of days that this thing has been sitting on my head, wanting to come out through my fingertips even as I had no idea how I would start it or where I would end it or what I would put in the middle of it—and, Jesus, now I’m quoting Seger, what to leave in, what to leave out—I’ve been thinking about a decidedly eighth-grade question: Who’s your best friend? Seriously, who? Is it your spouse, the person you spend the most time with, the person who hears and tolerates and rides out all the stupid shit you say, the person who’s in bed with you, who knows every embarrassing thing, who shares all the same things with you, who knows where the hurts and the hopes and the hesitations are? That would be a good answer, your spouse. In most considerations, yes, that’s absolutely the answer for me. Or is it your work confidant? Your childhood friend who has somehow endured? The high school classmate you didn’t know then but are connected with now and cannot imagine not knowing and loving? Your college roomie? Is it your neighbor, the person in the pew every Sunday at church, the father of your kid’s best friend? Or, maybe, is it someone who has rippled through your life, like a pebble sending slow-moving water rings to the shore? You had something going for a while, then life and distance intervened, then you picked it up and it was just as good as before—no, no, it was better—and then you set it down again, and then it came back one more time and it stuck for good. It has survived decades and losses and different cities and different sensibilities and different marriages and different jobs, and it’s the same thing it always was and it’s also something new, something evolving, something surprising and cherished. Couldn’t the person with whom you share all that be your best friend? Shouldn’t the person with whom you share all that be your best friend? Jon Ehret was my best friend. Jon Ehret is gone. How am I supposed to do this without him? Before I get into the various specific times and qualities and shared experiences that made Jon my friend, I need to answer broadly the question of why it worked for us, why we latched onto this friendship in the last decade of the previous century and saw it through for thirty years. No offense intended, but I don’t need to answer that question for you. The world can go on spinning if you don’t understand it, and while the world certainly will go on spinning if I don’t answer for me, here’s the deal: In hindsight, I can see it, all of it, what we shared and why it mattered and why it stuck. And hindsight is all I have, now. The drive Elisa and I never made to see him and Laura in their new house in Santa Fe, that’s not happening. His invitation for me to head down and meet him in Utah, where he was picking up a rescue bird (there will be more on this), the one I turned aside with “damn, my work schedule” and “invite me on the next one”—there won’t be a next one, and thus there will be no invitation. The last time I was in Buffalo, N.Y., his hometown (there will certainly be more on this), and invited him to fly out and he turned me aside with “damn, I’ll be at a wedding in Texas.” Yeah, that’s not happening, either. It’s all hindsight and memories and smart-ass ripostes on Facebook and a text thread on my phone that I will never erase, in hopes that I can someday bear to look at it again. That’s all there is. So here’s why it happened and why it mattered and why it stuck, and if this is too abstract, you’ll just have to trust me: Jon and I were the same but different, and this is the second time in a week I’ve used those words to describe the way I’m hard-bonded to someone. And because those bonds were so difficult for each of us to find with other people—there’s nothing like the unexpected death of your best friend to serve as a reminder that you make friends broadly but struggle to hold on to them deeply—we held tight to the fact that we found them with each other. I think we always knew what it was, but we took a long time to acknowledge it with a nod and longer still to say it and put wind under the words. We did, though. For that, I’m grateful. I have that, too, and so does he, wherever he’s off to. So, look, I should hope it doesn’t happen to you, but maybe it already has, and the longer you live, the greater the likelihood that it someday will. Your phone rings one bright day, and it’s Laura, and you know it when you hear her voice, because although you’ve known her for as long as you’ve known him, and you love her as much as you love him, he’s still the conduit by which the whole thing goes, and if she’s calling, that must mean Jon cannot, and so here it comes. This all occurs to you in a whisper of a fraction of a second. It’s fucking insane how fast and final it all is. Jon died at work, at the bird rescue center in New Mexico where he had found purpose in semi-retirement. He was in his joy, and then he was gone before his coworkers found him. Fifty-five years old. Heart attack, it would seem. No warning, no chance at intervention and another outcome. Gone. I spent the better part of a decade flat-out ignoring a condition that I knew would kill me if I let it. Jon had a lovely day with his wife, then went off to his birds, and never came home. We’re the same but different. Laura tells you all this, and you remember another phone call, 1993, Owensboro, Kentucky, to Buffalo, New York, and you were the one piercing the bright day and saying our friend, Brian, he’s dead, and Jon says, “Why?” And you realize that’s one hell of a good question, then and now, because it’s the only question you have: Why? Nobody fucking knows why. And you bounce to another memory, Brian and Jon at the center of it, where you’re at work as a sports clerk at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, couldn’t have been later than fall of 1991, and you’re making fun of your boss’ phone manner, because you’re 21 and a smartass, and you pick up a dead phone and say, “Staaaaar-TelegramsportsthisisEd,” because that’s how Ed says it, and all the editors on the desk are laughing, because you’re one funny sumbitch, and you don’t see Ed behind you and he says, “That’s pretty good. Good skill for your next job.” And here’s Brian: “I just got a warm feeling.” And here’s Jon: “That’s not a warm feeling. That’s Lancaster pissing himself.” And here you are, missing them. We met at the Star-Telegram. Jon was 24, and I was 20. He had a master’s degree from the University of Missouri in hand, and I was steadily on my way to bombing out of college for good. The same but different. He liked The Who and King Crimson. I liked Paul McCartney and R.E.M. I was making plans to move to Alaska (for the first time), and he thought that was the coolest thing in the world. I thought he was the smartest guy I knew, a brilliant layout man (we drew them in those days, kids) and someone worthy of emulation. We were big, lumbering guys, often more comfortable in our interior lives than we were on the outside. I covered up with a sort of zany bearing and kept a lot of my deeper thoughts to myself. Jon balanced anger and the most generous heart I've ever known. The same but different. Later, the connections went deeper. A weekend with the Ehrets after he and Laura moved to Buffalo, a day trip to Niagara Falls, an introduction to Newcastle Brown Ale, before it went all corporate. A snowy night, the last of the trip, when we ordered in and he urged me to get a cheeseburger sub and when I hesitated, he was all, “Man, it’s a cheeseburger on better bread. What’s the problem?” No problem at all. Delicious. And while we had surely eaten meals together before then, in my memories that’s the line of demarcation where shared food experiences became part of the deal: Jak’s in West Seattle, barbecue in Texas, seafood in Damariscotta, a legendary birthday meal at Walkers here in Billings on a minus-12-degree day, his urging me toward Ted’s Hot Dogs and Duff's in Buffalo, and my going to both, every time I'm there, even though we were never again there together, now much to my eternal regret. “Buffalo is a great fatboy town.” I say it. I live it. Jon said it first. In 1996, I decided, after some consideration, to seek out my birthmother. I told Jon what I was doing, because I knew Jon would have both an appreciation and a point of view, as an adoptee himself. He didn’t tell me not to, but he presented every you-oughtta-be-careful-here he could think of. He said he couldn’t imagine doing it. I did it anyway. Many years later, when he could imagine such a thing, I could give him some on-the-ground intel. I could validate the things he got right, contradict the ones he got wrong, and throw up flags around the ones neither of us thought of. He did it anyway. And, our being the same but different, we had more to talk about, in conversations that had the width and breadth and depth of galaxies. The kind we had so much difficulty having with other people and yet never had trouble getting into together. Another night of spotty sleep draws near, so let me just wrap it up this way:

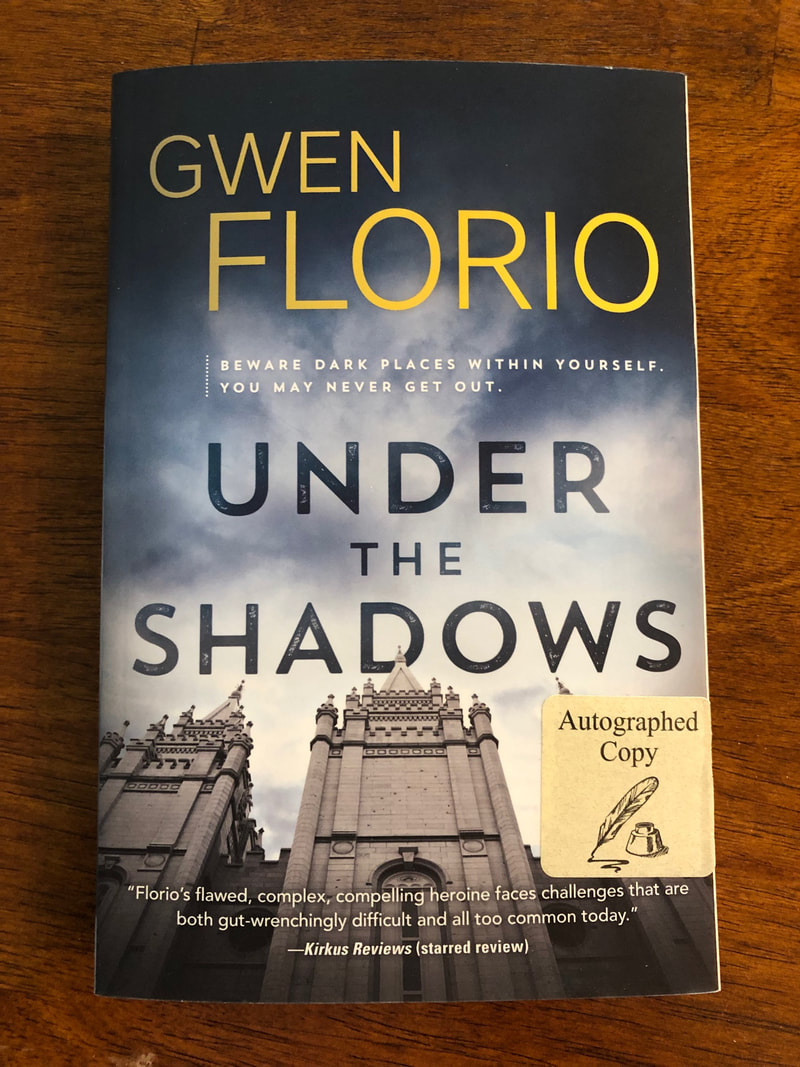

I have four brothers in a family line that looks like a tangle of kudzu more than it does a tree. There’s the brother I inherited when my mother and my stepfather got together. We lost him four years ago. There’s another who was born to that union. And there are two half-brothers who came with the search for my birthmother, the one I pressed forward with despite Jon’s admonitions, just as he pressed forward later with his own quest and his own questions. Neither of us, I think, would turn aside the decision we made after it was done. The same but different. Then there’s the fifth brother, the one I chose, and the one who chose me. I know he’s my brother because he told me so, and because I told him so, and because he was the kind of guy who didn’t use words he didn’t intend, and he told me these a long time ago: If you ever need anything at all, you tell me, OK? I took him up on it, too, in ways that seemed picayune at the time and register even more inconsequentially now. I was lucky, I guess. I never needed anything substantial and life-changing. A kidney. A roof over my head. A slayer of the wolves at the door. You know, the biggies. A heart. He filled mine. He broke it, too, just the other day. I’ll patch it up. He lives there now. 6/11/2021 0 Comments How to Spend a Day in Montana** — one of an endless number of permutations 9:50 a.m.: Head out of Billings due west with fair Elisa. Destination: Livingston, 117 miles down Interstate 90. There is much I could say about Livingston, although it would be nothing that hasn't been said before by better observers with keener insights. I made a friend laugh earlier today by calling it my Emergency Backup Montana Hometown. That's how I feel about it and the people I encounter there. (It was good to see you, Marc Beaudin. It's always good to see you.) 11:45 a.m.: Meet Kris King for lunch at Neptune's. In my early days of designing Montana Quarterly, Kris—one of the magazine's steady contributors (she does the author interview each issue)—gave me shelter on my overnights to Livingston for final magazine production. She's a whip-smart, offbeat, fun, funny, wonderful friend who has been extraordinarily kind to us, and it was the first time we'd seen her in more than three years. (We moved to Maine. We moved back. There was/is a pandemic.) If you've read my short story Remember Me in Istanbul, you might remember the ex-girlfriend's house that a guy and his wife let themselves into on a winter night. I modeled that house, and the spirit within it, on Kris' place. Now you know ... Around 12:40 p.m.: Head a few blocks over and get a sneak preview of the forthcoming Edd Enders Retrospective. (June 18-19 in Livingston, and you should totally go if you're within driving distance.) It's one magical thing to be able to stare deeply into a single Enders work, which we're fortunately able to do every morning, as one adorns our bedroom wall. (I mentioned Kris King and her kindnesses; the painting below is one, a wedding gift that we treasure.) It's quite another to see canvas upon canvas, crossing all eras of his wonderful work. What a thrill for us. Around 1:15 p.m.: Head out for Bozeman, another 26 miles west. We ended up at the Emerson Center, a place I'd often heard about but never visited. There, I dropped off a copy of And It Will Be a Beautiful Life to Rachel Hergett, one of Montana's premier writers about the arts. It was our first face-to-face meeting, another unfortunate byproduct of the pandemic. Can't wait to renew acquaintances again and again. I'm telling you, there was a buoyancy to the entire day in this regard. We're opening up, and hope is flooding in where darkness once settled. I'm allowing myself to dream of literary readings and concerts and sporting events and dinners with friends. Around 2:45 p.m.: Two more stops, both essential. First, Country Bookshelf, one of the finest bookstores you'll find anywhere. What a wonderful feeling to see the new book paired up in the window with Sweeney on the Rocks by Allen Morris Jones. Allen and I are doing a virtual event hosted by Country Bookshelf on June 30. We'd love to see you. And then to also see it on the shelves ... I also scored a Gwen Florio novel. Signed. Who's the lucky kid? Finally, no trip to Bozeman is complete without a stop at The Baxter and the little chocolate shop in the lobby, La Châtelaine. Elisa had the Hawaiian red salt caramel truffle. I had the French martini truffle (below). We split a Meyer lemon truffle. No regrets! After that? Eh, there's not much to report. Just a 143-mile drive through some of the most beautiful countryside there is, pulled along by the mighty, north-flowing Yellowstone River, a ribbon to guide us home. In the best iteration of myself, I try to be grateful for the life I have and the way I'm able to live it, but circumstance and the intrusion of transient difficulties sometimes get in the way. Perfectly natural, of course, but also something that can swallow your perspective if you let it.

Today was all gratitude all the time. For this life, for this place, for these friends, for these adventures, for the next bend in the highway ... 6/9/2021 0 Comments On Restlessness Vision of a sunrise near Douglas, Wyoming. My pipeline inspection equipment sits roadside in the foreground. Vision of a sunrise near Douglas, Wyoming. My pipeline inspection equipment sits roadside in the foreground. Originally published December 10, 2020 In the first piece I wrote for whatever this series of essays is becoming, I blithely noted a lifelong tendency toward restlessness. It’s a force that has driven research papers, inspired literature, informed film, and, in real-life situations, has ripped apart families, ended jobs, and launched fanciful and ill-fated dreams by the millions. A worthy topic, no? Here’s one small slice: In my primary career, that of a print journalist, I worked for ten newspapers (1) in seven states (2) over the course of twenty-five years (1988 to 2013). The shortest stint in a job was three months (hello, The Olympian, and the tumultuous year 2000 (3)). The longest stint was the final one, seven-plus years at The Billings Gazette, from summer 2006 to late fall 2013. In all of those years and all of those moves, I would pull up the stakes and fill the UHaul trailer for many reasons—money (4), status, opportunity, a sense of running to or running away—but the only factor that cut across every decision was this one: There looked better to me than here. That’s restlessness. If you read a lot of pop psychology (5), you come across the phrase “Wherever you go, there you are.” It has a subtle efficacy, straddling the line between inane (it is what it is) and something much more profound. In my case—and, I suspect, in many cases—it manifested like this: I could spot another job (believe it or not, newspaper gigs flourished in the early years of my career), I could apply for it and get it (because I was good at what I did), and I could pack up all my crap and haul it somewhere new, put down first and last on an apartment, find a new grocery store and some restaurants that suited me, meet new co-workers and bosses, and make a startling, yet thoroughly unsurprising realization days or weeks later: I’m the same broken jackass I was at the last place! It took me a long time to learn that I wasn’t feeding the part of me that required some care, the part that had yet to suss out the important differences between fulfillment and happiness amid the considerable overlaps. Not long after my initial career ended, I was picking through the debris field of a marriage with a counselor’s help, and with a lot of reflection and reading, some of these concepts started to click for me. I said to her: “Jesus. I must be the dumbest man alive not to have figured it out before now. (6)” And she smiled at me the way my mother sometimes does when I am in the vicinity of a realization without actually arriving there. “You’re in your mid-forties,” she said. “That’s when most men get it, if they get it at all.” (7) I don’t think I’ve gotten it. Sometimes, I think I’m asking the right questions, though. That’s progress. I followed my stepfather into journalism. The difference between us—and it’s vast—is that the job was something he did, not something he was. I used to think I’d figured out something vital that had eluded him, that by pouring myself into the job and remaining mobile (no kids, no attachments), I was making my career work for me. That was an illusion. Truth was, the job was working me, and I was willingly giving it some of my best years without insisting on my share of that time. My stepfather, meanwhile, rode out the vicissitudes of employment in a single place. Whether the job was good or bad or something in between, whether the bosses were genuinely caring or ogres, he did his work and came home to his family and his home and his life. He knew the difference between durable fulfillment and transient happiness. Like many dumbasses, I thought I was so smart. Let’s get back to restlessness. Certainly, that’s a condition that can lead a guy to choose the fleeting over the sustainable (8), to think he’s improving his lot when he’s really just going deeper into the hole. Restlessness, in itself, is not the problem. But restlessness is a gateway to transformative decisions, and those can be problems. Restlessness, applied well, can be a good and useful thing. And if restlessness is in you, I believe it’s there to stay, so better to manage it than to be managed by it. My newspaper career ended in 2013, and in the denouement, I was luckier than most: I granted myself release on my own recognizance. My first few novels had started to sell (9), I saw an opportunity to go, and I went. That first year of not having any obligation that I didn’t willingly take on, I slowly unwound the spring in my chest. I wrote when I wanted to write, I played golf when I wanted to do that, I traveled, I made merry, I finished crashing my first marriage on the rocky outcroppings of incompatibility and disregard. And somewhere in there, I felt the old stirring again. I wanted something to do, something to learn, somewhere to be. I was bored, a condition that’s the precursor to restlessness, which in turn is the spark that leads to decisions, good or bad. This is how I became a pig tracker. (10) In mid-October 2015, after a few weeks of dropping inscrutable hints about what I was up to, I wrote this on Facebook: I'm working on a pipeline crew, if I haven't been perfectly clear in my pig ramblings this week. Specifically, I'm a pig tracker. A pig is a tool placed in the pipeline that runs from point to point. Different pigs have different uses. Some clean. Some scan the interior of the pipeline. Some purge. And so on. A tracker stays in front of the pig—the tracker hopes—and records its passage at various crossings, gathering information on time, speed, etc. On a long, gentle run like this one, where the pig is moving about 3 mph and has to cover about 330 miles, that means the trackers work in shifts, day and night, 24 hours daily, all the time. We've been at it since Wednesday morning. We have a ways to go yet. I'm on the night shift. Midnight to noon. Then I find a hotel somewhere down the line and I bang out some sleep. I just finished that part. It's a weird, thrilling, lonely thing to skulk around the pipeline in the dark pitch of night. There's a lot of hurry up and wait on this job. There is, occasionally, a lot of hurry up and hurry up. You have to anticipate. You have to react. You have to figure out time and distance. It's fun. It's tedious, too, on occasion. Three days (nights) in, I'm exploring new frontiers of exhaustion. I'm reinforcing an old lesson, that Super 8's are, in many cases, not so super, and that Comfort Inns are not so comforting. … What I love is that I'm seeing the America I don't know well. Dirt roads and empty precincts and ghost houses and forgotten cemeteries, and a million other things. … I'm not doing it for money, although I'll certainly take it. I joke sometimes that I do it to stave off boredom, but that's too glib by half. No, it's something else. A chance to see and do and learn. All my life, I've been touched with wanderlust, that compulsion to see beyond present horizons. But I'm getting older and more rooted … I don't wander the way I used to. I miss it sometimes. Here, I can do it on my particular terms—work when I want it, without a desk on some office island, without some new corporate paradigm being triangulated by tiers of bosses. It's me and my night-shift buddy and our day-shift counterparts and the pig. We all keep rolling on. Pig tracking falls into the good-decision bucket. It's never been more than an occasional job—too many other things to do: books to write, stories to edit, magazines to design, life with Elisa to savor—but the work speaks to both who I am and what I’m fundamentally interested in. Time and speed and distance, man. Wherever we are, however we live, those are the measurements that build our equations. Without restlessness tugging at me, pestering me, maybe I never see that in such sharp relief. Endnotes (1) Deep breath: Fort Worth Star-Telegram; Peninsula Clarion; Texarkana Gazette; Owensboro Messenger-Inquirer; Dayton Daily News; Anchorage Daily News; San Jose Mercury News (twice); San Antonio Express-News; The Olympian; The Billings Gazette. (2) Shallower breath: Texas (thrice); Alaska (twice); Kentucky; Ohio; California (twice); Washington; Montana. (3) In less than a calendar year, I moved from San Jose, Calif., to San Antonio to Olympia and back to San Jose, where I clearly should have just stayed in the first place. (4) Not too damned much of it, in retrospect. (5) Guilty. (6) Hubris dies hard. (7) Men are in a lot of trouble. More on this later, I’m sure. (8) Guilty, many times. (9) Talk about transience. It was glorious while it lasted, though. (10) The main character in my upcoming novel, And It Will Be a Beautiful Life, is a pig tracker. This is not a coincidence. 6/9/2021 0 Comments The Shape of TimeOriginally published December 3, 2020

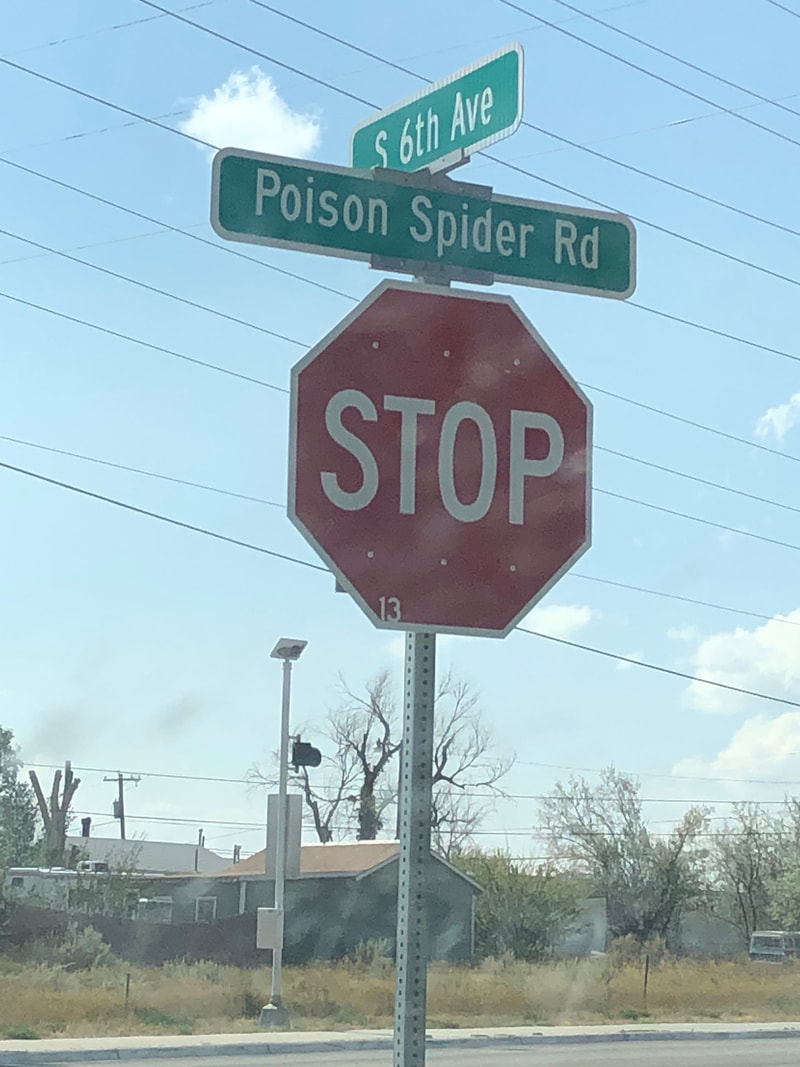

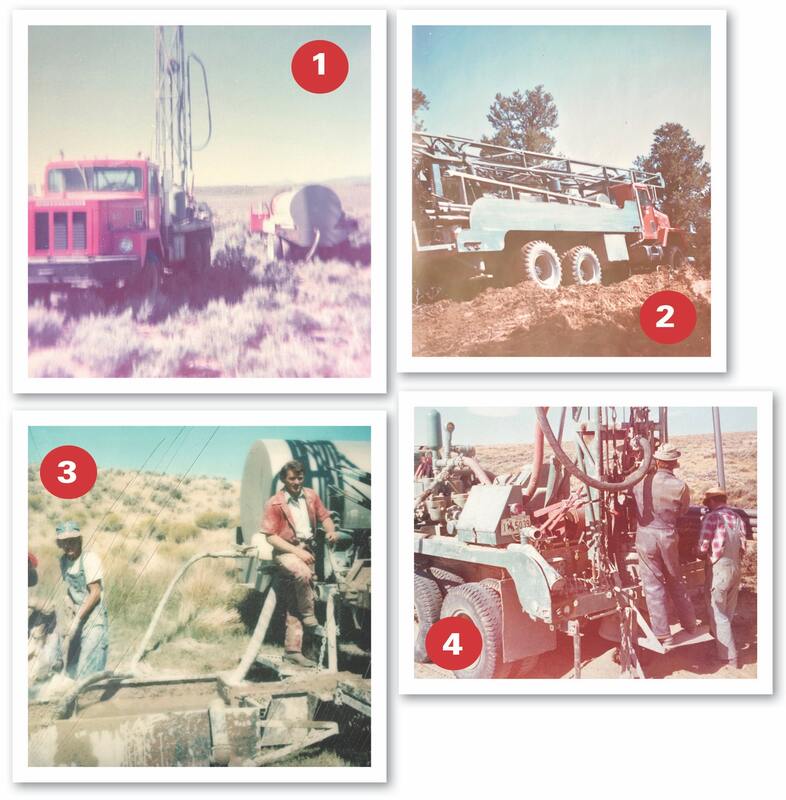

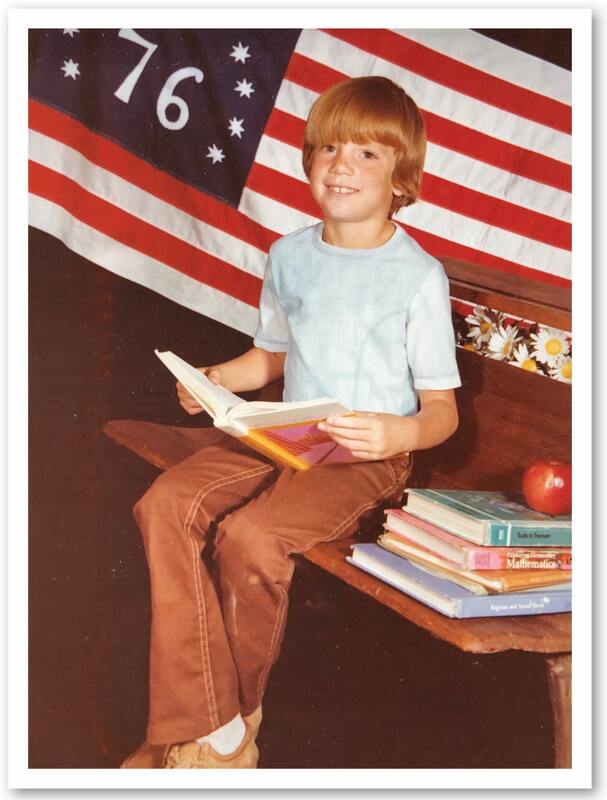

Just when you think Facebook has turned you away for good with its money- and data-grubbing perniciousness—and I do think this, on the regular—a friend posts something that commands your attention and sends you down the rabbit holes of memory and easy information, among the few reliable outposts in a pandemic that has separated us from each other. The compelling headline: “The Rare Humans Who See Time & Have Amazing Memories.” The friend who posted it, Ingrid Ougland, commented: “I see the months of the year as this sphere or oval, with December and January at the top, spring months slide down to the right, the summer months are at the bottom and kind of flat, then we climb back up with the fall months. I can’t visualize it any other way!” Envy was mine. I don’t see time that way at all. If anything, I see it in the old-timey movie effect of the passage of days, calendar sheets flying off in the wind, and suddenly Joseph Cotten (1) is a grownup standing in a place once occupied by a boy. Seconds tumble into minutes tumble into days tumble into weeks and months and years. Time compresses and stacks up, and I occasionally marvel that a colleague, blessed with what seems to be boundless youth, is, in fact, in his mid-thirties and should probably think now about doubling his 401(k) contribution. I wish I had (2). I would love to see coming time in colors or shapes, if only to make the inevitable passing of it more interesting. Upon thinking about it more—and herein lies the gift of Ingrid’s post: subsequent ruminations on time (3)—I realized that rather than seeing the days to come in some sort of order, I account for the days gone by with a storage system that’s varied in its cross-referencing and startling in the level of detail it allows me to access long after the time has slipped my grasp. It’s difficult to get at proving this thesis with any degree of abstraction, so here is a concrete example pulled from the archives, such as they are. Summer of 1976 A basic fact before we proceed, as it will clarify this anecdote and, in all likelihood, future writings: My mother and father divorced in 1973, when I was three years old. This is not an event that causes me to look backward in wistfulness, wondering if things might have gone better for me had those crazy kids stayed together. Indeed, things almost certainly would have been worse for at least two of us (my father, alas, never had it so good). So, please, if you feel compelled to pity, exercise it for a freckle-faced kid in some alternative universe who had to grow up in that household under the umbrella of that marriage. I’m fine. Really. What their breach did saddle me with was a sort of bifurcated childhood—two wildly different existences that I had to stitch together as a whole. During school months, I lived in a suburban house out of central casting, with two and sometimes three siblings (my stepbrother Keith being the wild card there), a mother who ran the homefront operation and a stepfather who worked hard and was present to his family life. Call it Cleaver-esque if you wish. That’s not an entirely on-target assessment—there are a few sprinkles of Yours, Mine and Ours, too—but if shorthand is your thing, I’m not going to let us get derailed on the particulars. Once school was out, my father would send for me, and I would spend summers with him in remote precincts of the West. Dad was an exploratory well digger, a job that scarcely exists anymore. (Slight deviation for self-promotion: My second novel, The Summer Son, will satisfy even the heartiest appetites for tales about well-digging.) He would drive from job to job with his truck-mounted drilling rig and a crew of helpers (sometimes one, usually two, and when I was around, I’d make three—or maybe two and a half) and would dig test holes that were subsequently detonated and picked over by geologists, whose task was to determine whether the findings warranted further extraction. These jobs lasted for varying lengths—sometimes a couple of weeks, sometimes a couple of months—and so I have this passel of childhood summers spent in such places as Montpelier, Idaho, and Baggs, Wyoming, and Limon, Colorado, and Sidney, Montana, and Price, Utah. I slept in motel rooms and on fold-out couches in fifth wheels, and, occasionally, in tents. Every morning, I’d ride with my father and his crew out to the fields where they were working, my sleepy head bouncing on Dad’s shoulder as he made the daybreak commute. We spent the summer of 1976 in Elko, Nevada, and here’s where the cross-tabbing of memory comes in. I remember it was ’76 because Dad’s helpers were my new uncle Barry and my new stepbrother Ronnie (4). I remember because Dad and his new wife and Ronnie and I were jammed up in a Holiday Rambler, often unable to escape each other, and I remember that the fissures in the marriage were almost immediately exposed by such unceasing proximity. I remember because “Play That Funky Music” was ever-present on the radio, and because I told Ronnie that I liked “Silly Love Songs” better and he told me I was just a dumb kid. I remember because, one day, another family in another trailer pulled in and set up camp, and their kid, a few years older than I was, punched me in the nose, bloodying it (and, perhaps, contributing to my fear of such confrontations). I remember because Dad and Uncle Barry responded to this assault in a way that can be described, only with considerable charity, as disproportionate. They carried baseball bats to the other family’s campsite, waggled the lumber with menace, and suggested those folks move along. Dad still tells this story from time to time, when he gets enough alcohol in him to open the dark rooms of his recall, and he always finishes with a laugh and a “man, you’ve never seen anybody drive away so fast.” I remember because I have to live with two distinct reactions to that sight, separated by years of reconsideration: In the moment, as a bloodied little boy, being in awe of these men who stepped in on my behalf, as if they were superheroes. And now, much older than either man was that day, wondering what the hell was wrong with them. Forty-four years’ worth of calendar pages have been cast to the wind, and I can sit here today and close my eyes and see the terror on the faces of that man, his wife, and their boy. I am much more in tune with how scared they were than I am with how I felt as a six-year-old who watched the scene unfurl. Summer of 2006 On Day 1 of my two-day move from California to Montana, I skirted along Elko on Interstate 80, and recall was stoked not just by the name but also by the bends in the highway and by the hills in the distance. I guided my pickup-UHaul combo off the interstate and, with neither GPS nor memory of the name of the campground we had stayed in thirty years earlier, I drove right to where it was. I knew the direction and the topography, I knew the hill it sat upon, and I knew the turns I had to make to get there. Had it occurred to me that this was unusual, I might have made more of it, but I’d been doing similar things in other places throughout my adult life, and I’ve continued to do it since. Drop me most anywhere I’ve spent an appreciable amount of time, whether as a child or a man, and I can find my way to the places I occupied in some past era of my life. And once I’m there, the time gone by indeed has shape and color. It settles uneasily atop or alongside whatever is happening there now. I can stand in front of my first house, off Poison Spider Road in Mills, Wyoming, as I did this past summer, and I will see the boxy white house with the single-car garage, ever-present in my memories since I last lived there in 1978, and I will also see what it is now: a sort of cinnamon red, the garage long ago converted into more living space, the street out front paved rather than dirt and gravel. I can connect with what was and allow it to coexist with what is. I have to. There is no other choice. Time is a slow-motion wrecking ball—it wipes out businesses that once existed on corners, housing developments, schools, the names by which we know things. Few human constructions can survive it. But none of that matters if it’s the corners to which you’re beholden and not what sat upon them while you were passing through. Those corners call to me. Endnotes (1) I’m not sure why Joseph Cotten popped out of the ol’ cranium for that example. I’m not terribly familiar with the bulk of his work, although he looms large with me for two reasons: First, Shadow of a Doubt might be the best movie ever, and yes, I’m willing to fight you. Second, I always momentarily confuse him with Josef Sommer, which is thoroughly inexplicable. (2) Seriously, retirement is a pipe dream. I’m going to have to die with my hands on the keyboard. (3) I mean, I’m not Proust, but I do spend an inordinate amount of my energy ruminating on the illusions and erosions of time. (4) While it’s true that I’m an ardent believer in the benefits of a necessary divorce, I really would like to urge those among us who cannot sustain the institution of marriage (in this case, I’m looking at you, Dad) to keep the rest of us out of it. At one point in my young life, I had three brothers and three sisters, thanks to the kudzu-like entanglements of several mergers. And then, with the stroke of a divorce judge’s pen, half of them were gone. I did not get a vote in the decision to add these sort-of siblings in the first place. Nonetheless, I accepted them as my own and loved them. I also didn’t get a vote in their departure. It sucks. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed