|

We've been headed here all along, haven't we? The book's first full chapter begins with Nathan. The book's last interceding chapter ends with Nathan. He stands as the pivotal character in an ensemble, the one who can still change his course, if only he has the courage. Others have made their choices and lived, or died, with them. A lot is behind Nathan. More could yet be ahead. There's not much else I want to say, except this: For me, the suggestion of future change is the most satisfying part of literary characters. I'm far more interested in the idea that they could change than the actual shape and scope of that change. It's why I like open-ended endings so much: Presumably, life goes on, until it doesn't. While we're sentient and breathing, it's within us to deviate our path. Thanks for reading. (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) Previously

0 Comments

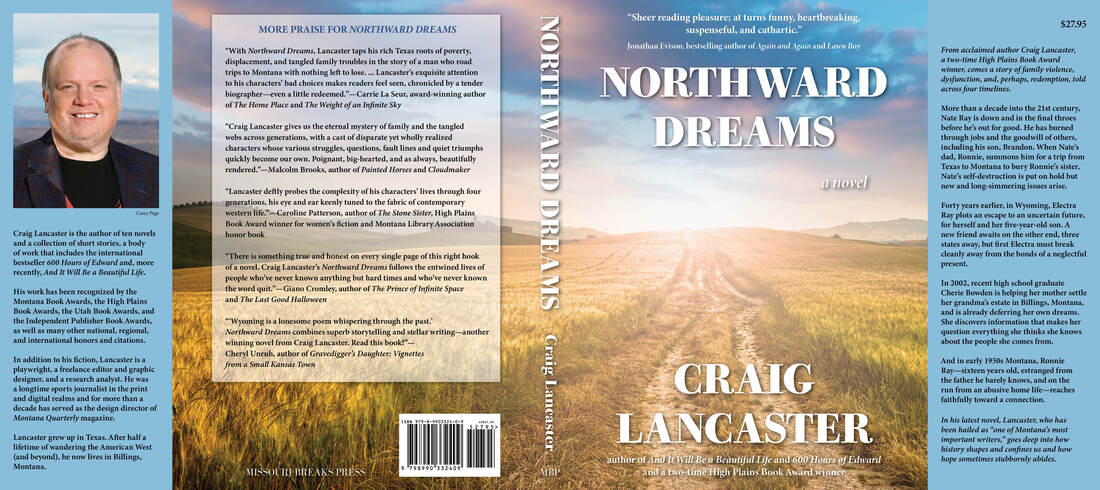

So I hear what you're saying: "Craig," you're saying, "just how much of this thing is memory and just how much is imagination? You're hinting at both, but you're not really giving me the scoop. Is Northward Dreams mostly memory or mostly imagination?" Yes. That's my answer. OK, OK, so as we dive deeper into the characters and their breakout chapters, here's where the imagination definitively comes in. Erica Stidham--Charley's eventual wife, Ronnie's former wife, Nathan/Nate's forever mom, a woman with her own power dependent on no man—is no longer with us. The woman whose life provided some inspiration for her—remember the great gift I talked about in the previous installment—is most assuredly still here. She's my mother. I ought to know. You happy now? A minor bit of craft talk: When I start writing something new, I usually know little about what is going to happen but much about who will be in the middle of it. That was mostly true for Northward Dreams, save for one character: Electra. I always knew she'd be leaving early, mostly because I deeply knew the pain her son was in, and would have to be in, and would spend the story fighting against. And sure enough, when the structure of the story began taking shape, we eventually got to Electra, and her busting loose from the established timelines had to happen in a way that fortified the loss of a little boy who grew to be a good, flawed, troubled man: It's one of the cruel jokes of the universe, that he'd come to you not a year and a half ago and said, Am I going to die someday? ... You'd had to sit him down for one of the Big Talks that's in all the child development books, and you'd had to explain that, yes, he will die someday, we all die after all, but not for a long, long time. Are you and Charley going to die? Yes, but not for a long, long time. Daddy? Yes. But again... More craft talk: I mention empathy a lot. It's an essential ingredient. When a memory prompts an idea, imagination sweeps in and leaves you with characters whose defining characteristics and subtleties are yet to be discovered. Empathy—understanding them and their thoughts, choices, and motivations—is the pathway to realizing what you wish to do with the work. I found empathy with Electra, and found her to have surface-level commonalities with my mother but also to possess qualities that were uniquely hers. I didn't have to imagine my mother's death—and good, because I would have hated to contemplate that. I had to feel what losing Electra would be like—her own sense of it, yes, but also, and especially, what it would do to her child. It was a gut punch, both ways. (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy. (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) Previously Now that Northward Dreams, at long last, is out in the world and available in hardcover and e-book (with the audiobook on the way!), I'm enjoying the payoff for all the lonely work of writing it and preparing it for delivery: the idea that there are people out there reading it. (Thank you!) If you're one of those people, you didn't have to go far—the very first words—to encounter one of the book's devices, for lack of a better word. Spread out among the 32 numbered chapters of the book, which encompass four timelines (1952, 1972, 2002, 2012), are nine chapters that focus on individual characters who inhabit the book. These chapters—which I've heretofore been misnaming as intercalaries—exist outside the story's established timelines and illuminate aspects of the characters that inform the whole of the narrative. They're also written in second person, a choice I expanded on in this interview with Chérie Newman: I think I went with the second-person point of view initially just to talk to them: Here's what's happening to you, what you're feeling, why it has gone the way it has. Any notion I had about changing that up went away once I saw the effect. There's an immediacy to the POV. Those characters are illuminated in ways they couldn't have been even in close third person. So that's why I did it, but this isn't really about that. (It's not expressly a craft talk.) Instead, I want to dig into who these characters are and why they spoke to me—and why they allowed me to speak to them—without giving away the essential plot, so to speak. (Before I get too far into that, about the errant use of intercalary: These chapters don't quite fit the accepted definition because they do involve main characters and are less about theme, I think, than they are about backstory. For a more traditional view of the intercalary, think of the turtle chapter of The Grapes of Wrath. I certainly do—I referenced it many years ago in a short story.) Opal goes first because...she goes. She dies, right there on Page 13: You kneel, the knees of your jeans in the mud, and you take the clipping shears from your apron pocket. You size up the job, and you pitch forward into the bush. Two crows, languid on the telephone line above, bear witness. Across the way, the hammering goes on, beating out a rhythm, a simple song for the dead and gone. Here's the thing about Opal, though: She is, in a significant way, the master key to the story, the connector of 1952 and 1972 and 2002, when she leaves us, and even 2012, when she's a full decade gone. Without Opal, the connections among Ronnie and Cherie and Nate and Electra—the four primary characters of those timelines—lack resonance. And without those four, Oscar and Anna and Charley and Brandon are four characters in search of a story. In subsequent installments of this series of posts, I'll introduce you to all of them. You'll just have to believe me that they all fit, eventually. Or read the book, please! (Be sure to note in comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.)

I'm going to tell this story only once, for posterity, perhaps, or maybe just because it's so bizarre that I'll want to have this record in a year or 10 years or 20, when I won't remember the fine details anymore.

Soon—very, very soon—my 10th novel will be out in the world, available in a variety of formats through just about any retailer that sells books. For the longest time—and that's part of the story, really, the loooong time—my assumption was that it would be called Dreaming Northward and would be released by the publisher behind my previous book, And It Will Be a Beautiful Life. We had a good relationship, this publisher and I, and I expected our association to go on and on, to the end of my career. But it didn't go that way. On March 11, the day before Dreaming Northward was set for a fractured release, with the e-book going out first and the hardcover and audiobook supposedly to follow at some ill-defined point, I asked the publisher to cancel the book and immediately revert all rights to me. (That request was granted, for which I am grateful.) I will not engage in a blow-by-blow description of all the ways I believe my trust and faith were compromised. And I have no desire to harm this publisher; indeed, despite it all, I have great affection for the guy running the operation and would even consider a return if certain factors that beleaguered this book were dealt with and overcome. Obviously, the publisher might not be interested in a reunion, given the events of the past week. I'm just being clear about where I am on this. I'm not mad. I'm not even hurt, not really. I'm just sad and disappointed over the outcome but also resolute that it had to happen. Dreaming Northward is gone. Northward Dreams lives.

So why did I do it? It's not like publishing contracts are easy to get. It's not like I'm a well enough known quantity that I can act like a spoiled child and get away with it (or even foment the impression that I'm a spoiled child). It's not like I have this notion that independent publishing is a dream trip. I've taken it, and it's not. It's a slog. It's exhausting. It's an endeavor undertaken with the odds ever against you.

So first, let me say this: I'm a lot of things, but I'm not a spoiled child. Second, I've been around enough publishing blocks—self-publishing, small publishing, big publishing with powerhouse marketing and backed by big-time agencies, etc.—to know that almost everything is a crapshoot for almost everybody. In this case, the promises made to me about how my book would be positioned and the marketing muscle that would be put behind it were, in retrospect, dependent on a round of funding my publisher kept promising was imminent, month after month after month. After this book slid from its original publication date in June 2023 all the way to the doorstep of last fall, I asked for a Spring 2024 date, thinking that might provide the necessary buffer for the funding to come through and for the marketing pieces to be put in play. Many, many times, I was told the funding was just a signature or a courier away from being realized. Month after month, it didn't show up. In late January, I asked if the March 12 release date was going to hold. Yes, I was told. But in the end, that cratered, too. The e-book was definitely going to come out, but the hardcover would have to be delayed. That was the eventual word. How long would the delay be? No one could say. I wasn't comfortable, but I was willing to go along and have faith. We were so close. Then came March 11 and word of another funding delay, and that ended my faith. I couldn't trust that the hardcover edition would ever come out. The more I considered it, the more I feared that the e-book would get launched, nothing else would come up behind, the whole thing would eventually crash, and I would have to pick up a barely breathing book and try to resuscitate it on the fly. It was just a bizarre episode. Not two days before I asked for a reversion, I stood in front of 50 people at the Billings Public Library, talked about And It Will Be a Beautiful Life (the most recent selection for the One Book Billings community reading program), and premiered a video about Dreaming Northward. (The video has been edited in light of recent events and can be seen below.)

I had every expectation that my book release, flawed as it might have been, would be realized. Then Monday dawned, and with it came another funding delay and my publisher's declaration that he was leaving his post for a couple of weeks amid this latest setback. He said he had to shore up his affairs in light of the situation. That was the final blow to my trust.

I asked for my book back. I made arrangements to publish it myself, through my own boutique house. In a frenzied 24-hour period, I conjured a new title, designed a new jacket, got hardcover files together and uploaded, got the e-book file to my designer, revamped this website, reworked marketing materials (such as Facebook headers and event posters), contacted booksellers and librarians who have already booked me, and, somewhere in there, bagged a few hours of sleep. Just last night, I approved the hardcover files with my printer/distributor and officially set a publication date: March 19, 2024. As I said on Facebook: I lost a week. I gained my whole book. It's not remotely what I anticipated or wanted. But it's my project now, and I'm determined to push it as far as it will go. I'll have to do some fundraising. I'll have to come up with some clever and creative marketing approaches. I'll have to look for people to say yes. Bring it on.

So the e-book comes out first. What's the big deal?

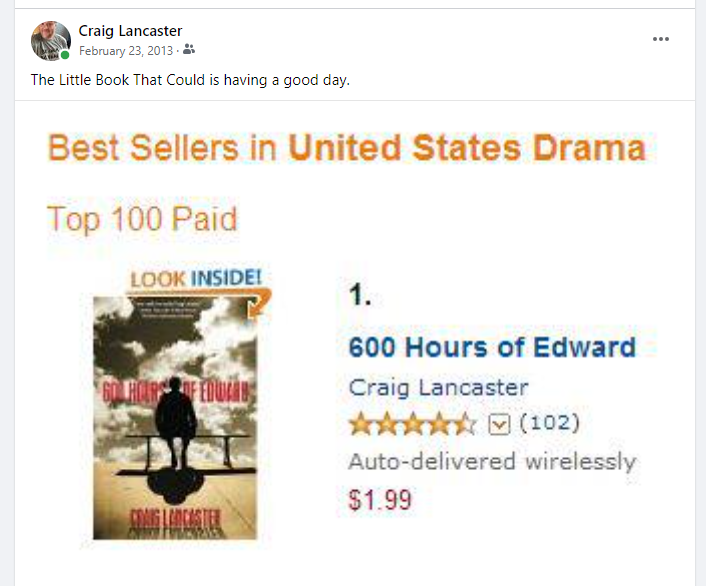

Look, I love e-books. That's how thousands and thousands of readers have been exposed to my work. But my passion lies in supporting independent bookstores, and this was always going to be a bookstore book. There were grand plans—personal letters to booksellers from my publisher and me, flashy campaigns through Bookshop.org, maybe a tour. All dependent on funding, of course. And it wasn't so much that the e-book would go first that bothered me as the fact that I no longer believed the hardcover would appear at all, given the dead promises along the way. There was no way to be OK with that. My faith was expended. That doesn't mean I wish bad things for my old publisher now that my book is out of the mix there. On the contrary, I hope I'm extraordinarily wrong about my suspicion of how that situation will finally play out. I hope he calls me in a few months and says, "You should have waited, buddy boy," and sends me videos of his lighting cigars with hundred-dollar bills. I'd be thrilled for him because he's a good man, and he was hands down the best editorial partner I've ever had. Publishing is hard work. It's even harder on a shoestring budget (as I well know and am about to experience again). I don't hold my publisher's inability to do right by this book against him. He was trying. Hard. But it wasn't happening, and in the face of that reality, my loyalty had to be to my work. In short, even if my publisher's highest ambitions come to fruition, I made the right call, given the track record. At the moment I had to make a decision, I made what I consider to be the brave one. I chose my work. I chose my sense of integrity. "If it's not hell yes, it's no" is a great clarifier in matters of choice. Sticking to that rubric, even when the answers aren't easy and even when the wish is for a different outcome, can keep one from committing reservedly to something that requires one's whole heart. I was no longer at "hell yes." Therefore, it had to be "no." Here's the dirty little secret of my life as a novelist: I'm terribly read, at least in the realm of fiction. When it comes to nonfiction, poetry, current events, studies about financial inclusion, etc., etc., things look better for me, but fiction is a weak spot in my repertoire. The reason is both simple and counterintuitive: I write fiction. I'm too busy doing what I do to spend as much time as I'd like on what other people do. This year, however, I've decided to dedicate a small part of each day—30 minutes, in the wee hours of the morning—to reading fiction. This means I move slowly. It also means I get to savor something—or live long with the bitter taste, depending on how I'm feeling about my selection. To focus my efforts, I've decided to read works that are generally regarded as classics. This, of course, still leaves a wide field from which to choose, and the criteria for curation are mine alone. My only rigid rule: If one month I read a work by a man, the next month I will read a work by a woman. And vice versa. I also intend to take in diverse work*, in as many forms of diversity as I can. Have a suggestion for me? Drop it here. I have every expectation that this will be a humbling exercise. I'm going to read books I should have read a long time ago, and I'm going to be accountable to myself here, which means I'll be accountable to you. I fully expect to be greeted with incredulous declarations of "you haven't read that book, you philistine?", and I rather think my layman's approach to literature—I am not, by any stretch, an academic—will expose my shortcomings in assessing what I've read. On the other hand, I will receive these books as I imagine most of their readers, historically, have received them. And to this reception I will bring some amount of knowledge about the decisions a novelist makes as he/she/they do the work. Today, I start this journey with The Razor's Edge, by W. Somerset Maugham. How I came to this one was a bit haphazard: I had gone to my local library to pick up To the Lighthouse, by Virginia Woolf, as my starter. No copy was available, so I perused the shelves, waiting to be inspired. I'd read Maugham's Of Human Bondage in high school and remembered liking it, although as god is my witness, I cannot recall why or even much about the book. Too many intervening years. So I plucked The Razor's Edge and started there, with the library loaner copy having a return date. I bought To the Lighthouse at This House of Books, so it's up next. The Razor's Edge  By W. Somerset Maugham Publisher: Vintage (2003 edition) Originally published: 1944 My review, in a nutshell: I couldn't wait for it to end I should say this in the book's favor at the outset: I found much to admire early on, particularly Maugham's style and sentences, which I think are what I also enjoyed as a callow teenager when I tackled Of Human Bondage. But in the final analysis, I found the book to be maddening and dense, and in the last 30 pages or so, rather than savoring each tender morsel, I found myself hanging in there out of pure animus and a desire to conquer it. Among the aspects I found irksome: 1. The decision to filter everything through a secondary or tertiary party—and to call that narrator "Mr. Maugham"—struck me as ineffective and bizarre. The central character—the one whose journey of self-discovery confounds the well-moneyed people who know him—is former military pilot Larry Darrell, and yet we don't experience his transformations through his eyes but rather through those who think they know him and, in small snippets, from Larry himself on those rare occasions when he drifts back into the social circles he knew as a younger man. Until we do see it through his eyes but have given up. See Point No. 2. 2. The book makes a great fuss of Larry's inscrutability and unwillingness to share much of himself ... until he drones on for hours toward the end of the book, telling Maugham (the character, not the author, but who knows?) all in hopelessly long paragraphs that unfurl endlessly, no bit of arcana to obscure to leave out. To what end? We don't really know. Larry used to not talk of himself much at all, and at the end he cannot shut up. I didn't buy it. 3. This, no doubt, is the perspective of someone born late in the 20th century and thus not applicable to the audiences that received this book in 1944, so take it as you will: I had quite my fill of snobbish society early in the book, which made the rest of it a gutful as I slogged through the (many, many) remaining chapters. Elliott Templeton, the uncle of awful Isabel, who loves Larry but never has him, is charming enough and decent enough, but I'd had enough of him long before he exited the stage. Enough, too, of Mr. Maugham (the character, not the ... oh, hell, never mind), although I'll grant you that he was a bit more accepting of human frailty and thus was easier to take. It's nice when you can write yourself—or your avatar of the same name, anyway—to best advantage, I guess. I found this to be a rare case of my vastly preferring the movie (for me, the 1984 version starring Bill Murray, although I have also seen the 1946 original starring Tyrone Power). The movies center on Larry as the main character on a baffling—to onlookers—search for meaning. The book, with Mr. Maugham (the character, not the ... well, you know) as the portal for all perspectives, mostly renders Darrell's experiences as nothing more than long soliloquies by the other characters. It's not nearly as effective. Those characters are glib and haughty and annoying, and they wear on the reader. This reader, anyway.  *—Now, about diversity ... Years ago, a friend with whom I eventually lost contact, knowing I was interested in all things Hemingway, gave me a book titled With Hemingway. In that book, written by a young North Dakotan named Arnold Samuelson, Hemingway offered a list of the books one must read to be educated, by Papa's estimation. "Some may bore you, others might inspire you, and others are so beautifully written they'll make you feel it's hopeless for you to try to write." Here's the list: The Blue Hotel and The Open Boat, by Stephen Crane Madame Bovary, by Gustave Flaubert The Red and the Black, by Stendhal Of Human Bondage, by W. Somerset Maugham Anna Karenina and War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy Buddenbrooks, by Thomas Mann Hail and Farewell, by George Moore The Brothers Karamazov, by Fyodor Dostoevsky The Oxford Book of English Verse The Enormous Room, by E.E. Cummings Wuthering Heights, by Emily Bronte Far Away and Long Ago, by W.H. Hudson The American, by Henry James It's entirely possible I'll poach a title or two from Hemingway's list—I very nearly picked up Madame Bovary for my third selection before opting for a Bradbury book—but this roster is notable for several things that don't appeal to me, notably that only one woman, a Bronte, passed muster. I think I can do better than that. Gonna try, anyway. 2/23/2024 0 Comments An Artifact of a Bygone EraThank goodness for Facebook memories—I guess—as I otherwise would not have seen that I posted this picture and this comment on my timeline 11 years ago: Eleven years seems like a long time ago, perhaps because it was a long time ago. And 11 years ago, I would have been loath to discuss the following topic, which I'm only too happy to discuss today: I am not, for the purposes of self-identity or self-esteem, a bestselling author or an international bestseller or an author whose works have been widely translated or a two-time High Plains Book Award winner. I am, for the purposes of advertising and marketing, all of those things. The differences between am not and am are profound, and learning to understand and appreciate those differences took me a long time and no doubt occasionally made me fairly insufferable. Live and learn. I think I can tell you exactly how my first novel, in 2013, went straight up to No. 1, if I may borrow from Bad Company. Of course, I'm biased in the analysis, so I'll tell you that writing a good book had something to do with it. I'm a realist, too, so I'll also say it had far more to do with a rising tide of readers eager to acquire e-books, a publisher with unparalleled access to those readers, and a price that encouraged those e-reader-wielding book lovers to take a chance on my novel without an onerous investment. Consequently, that book—and I—had a very, very good day (and week and month, and, really, a few good years). I'm nothing but grateful. And, sure, from a marketing perspective, I appreciate the bestseller label. It has had a far longer life than the actual bestselling ever did. We—the royal we of the publishing universe—hold fast to a bestseller status because we think it helps sell books. We festoon award stickers on hardcovers and paperbacks because we think it helps sell books. We seek out testimonials from other authors because we think it helps sell books. (And, on the flip side, we try to say yes to authors asking us to supply testimonials for their books because we really, really hope it helps sell books!) And at least to some extent, I'm certain all of that is helpful. But the degree of help is ephemeral and unmeasurable, and that's why the best an author can ultimately do is to (a) write the best book possible at the time of the undertaking and (b) work as hard as possible on its behalf once it has emerged into the world. Those are controllable factors. The rest...are not. Harder to accept, I think, is the truth that my friend Allen Morris Jones, one of my favorite authors, recently laid bare in his excellent newsletter, Storytelling for Human Beings: "There is very little rhyme to literary fame, almost no discernible reason. The breadth of your talent and the depth of your persistence are only a couple chunks of okra in that roiling, haphazard whatchagot stew of literary recognition. A few lucky souls end up making a reputation and a living. The rest of us tread water, watching our ship churn away over the horizon." That's sobering, yeah? Still, sobriety is vastly preferable to drunkenness on one's own marketing materials. I had a blast that day 11 years ago, I sold hundreds and hundreds of books, I made a fair amount of money (all of it now gone), and I didn't have to do anything stupid in the bargain. I'll continue to use the bestseller label, even if the fuller context is "author of a handful of bestselling books and a larger handful that you probably haven't read, not that he's complaining."

Luckily, the limited room on a book cover rewards brevity in these matters. 11/4/2023 0 Comments Saturday Morning Craft Talk......if you'll indulge me. Tonight, Yellowstone Repertory Theatre wraps up its nine-performance run of Straight On To Stardust, my first full-length play. To say it's been a privilege would be a damnable understatement. To say it's been fun would be to undersell the word. To say I'm going to miss it... Well. Yeah, I will. I hope this isn't the end, but if it is, I couldn't have enjoyed nine days and nights any more than I have, and I certainly couldn't have seen my play taken on a maiden voyage by any group more loving and talented than the YRT ensemble and its intrepid leader, Craig Huisenga. I'm a writer, so I'm not terribly unusual in that I want nothing more than to undertake the next writing project. Another play, perhaps. Maybe a novel. A short story. I don't know. The idea will tap me on the shoulder soon enough, and I'll be in my seat, doing what I do. In the meantime, I'd like to see where else Stardust might alight. Have some ideas? Talk to me. Want to download the media kit and read an excerpt, see some photos, read some reviews? Have at it. But about that craft talk... Occasionally, I'll read a book review, or even the book itself, and the reviewer and/or I will be awed by the incredible sweep of a story, how it captures an era or a movement or a moment in our lives, and I'll have that inevitable feeling of being unworthy: How, I'll wonder, can I call myself a writer of fiction when I lack the imagination to conjure a story that so richly conveys detail and so expertly takes in such abundant themes? This is doubt, by the way, standing on the shoulder and whispering poison into the ear. The problem: Those in the throes of such doubt often lack the ability to stand back and gain perspective in the moments when they most need it. So we ask ourselves why we should bother when someone else, or many someones else, do it so well. In my calmer, less doubt-ridden moments, I'm able to center myself in this truth: I am not, as yet, a writer of sweep. I am a writer of the interior, in ceaseless exploration of fear and sloth and errant motivation and mistrust and love and betrayal and every possible in-between that makes us maddeningly human. I write from the inside out to better understand not just others but myself. Maybe, ultimately, especially myself. On that subject, I am taking a lifelong postgraduate course from which there is no bestowing of a diploma. There is only the next lesson. I've been thinking of these things a lot in these past few weeks of repeatedly watching Straight On To Stardust play out in front of me. This is a story of family fractures and of interior lives that are explosive in combination: a son who misses his mother and stretches out, flailing, for his father; a daughter who searches for a way in with her inscrutable dad; an ex-wife who still loves the man who denies her intimacy; a friendship held, frozen, in time and the cosmos.

When you reside in the interior and work from there, you discover, eventually, that most of the scary things behind the door you keep trying to bust down have their roots in childhood. Anybody who's been in therapy knows this; it's why counselors start there as they help their patients tunnel into the now. Generational trauma flows from child to child, often through the clearinghouse of adulthood. When we don't handle our shit, we roll it downhill to the next person. Someone, eventually, tries to pay the overdue bill. It's a hell of an inefficient way of living, with incalculable damage inflicted in the main and on the margins, but here we are. Again and again and again. It doesn't take much imagination to consider how these interior damages have great reach beyond our own lives. How might the life of one particularly public narcissist have gone differently had he been hugged more often by his father or been told that he was loved? Or let me take this to an intensely personal place: Why did I equate love with eventual abandonment throughout my 20s and 30s and 40s? (It's rhetorical, this question. I know the answer. I know it now. I learned it the hard, necessary way in my mid-40s.) It's a hell of a thing, this trauma. It's given to us, in most cases. No instructions, no way of opting out, here it is, and it's ours to carry. It often happens when we're young, but there comes a time when that's no longer an acceptable excuse for our clinging to it. Yeah, we were just kids, and yeah, it should have gone another way, but it didn't, and now the onus is on us to not inflict it on someone else. You up for that, the responsibility of that? Some of the most wrenching, yet illuminating, stretches of my life have come while I strained to get to yes when faced with that question. It's why I write. To hold these things up to the light. To understand them. Sweep? I'm not thinking about sweep. I'm thinking about getting through this life. How do I do that? How do the characters I'm living with do that? Can I listen closely enough, feel acutely enough, be compassionate enough on their journey? Can they find their way through? Can I help as I walk with them? I want to. I need to. 10/7/2023 0 Comments Saturday Afternoon Craft Talk...

...if you'll indulge me.

This will be focused not on prose, necessarily, but on the blending of words, inspired by a lyric I can't stop thinking about. But first, a digression: At Christmas last year, my wife gave me a lot of stuff for my home office, knowing I would be starting a new job early in the new year. Chief among these gifts was a turntable, which has gone on to spur some prodigious purchasing of vinyl. Old stuff, mostly, but some new, too. One of the latter is the latest from Ben Folds, titled What Matters Most. I love this album. Love. It. And no song holds my adoration more than the last one of Side A, called "Kristine From the 7th Grade."

The song—about ending up on the mailing list of a QAnon-style conspiracy theorist the narrator remembers with fondness from long ago—has all the wonderful Folds touches that I've admired for almost half my life: melancholia and tenderness and empathy and yearning. It also has a sentence construction that just enchants me:

I got the emails these last two years, every day...

There's something about the order of things here that gives me the same spinal tingle I experience when I read a moving passage of prose, or hear a line delivered just so on film, or what have you. A journalist might be inclined to rearrange the boxcars into a more orderly procession: I got the emails every day for the last two years. But to my way of thinking, the magic goes right out of it if you do that. The point here is every day. It's the punctuation. The two years might have been endured if not for the every day. Paired with Folds' inimitable ability to tap into the emotion of what he's singing, the whole effect is purely and sadly beautiful.

Now, I don't know enough about songwriting to say with any authority what Ben Folds was aiming for here. Any number of factors could have influenced his decision about ordering the words. All I know is the feeling his choices, arranged this way, draw out of me. When my wife and I got together, we talked a lot about writing, which shouldn't surprise anyone. But as we dug into craft and habit and the rest, we also talked about what we admire in each other. I'll always be moved by her telling me that I arrange things in surprising patterns, with combinations and riffs that it wouldn't occur to her to try. (And why should she? Elisa is already a great writer.) I can't say I do so with any sort of overarching plan: By God, even if it kills me, I'm going to arrange these words in surprising patterns. But I do listen to the beats and consider the light and color of what I'm writing as much as I do what the words actually mean. It makes a difference. At least to me. In Parting...

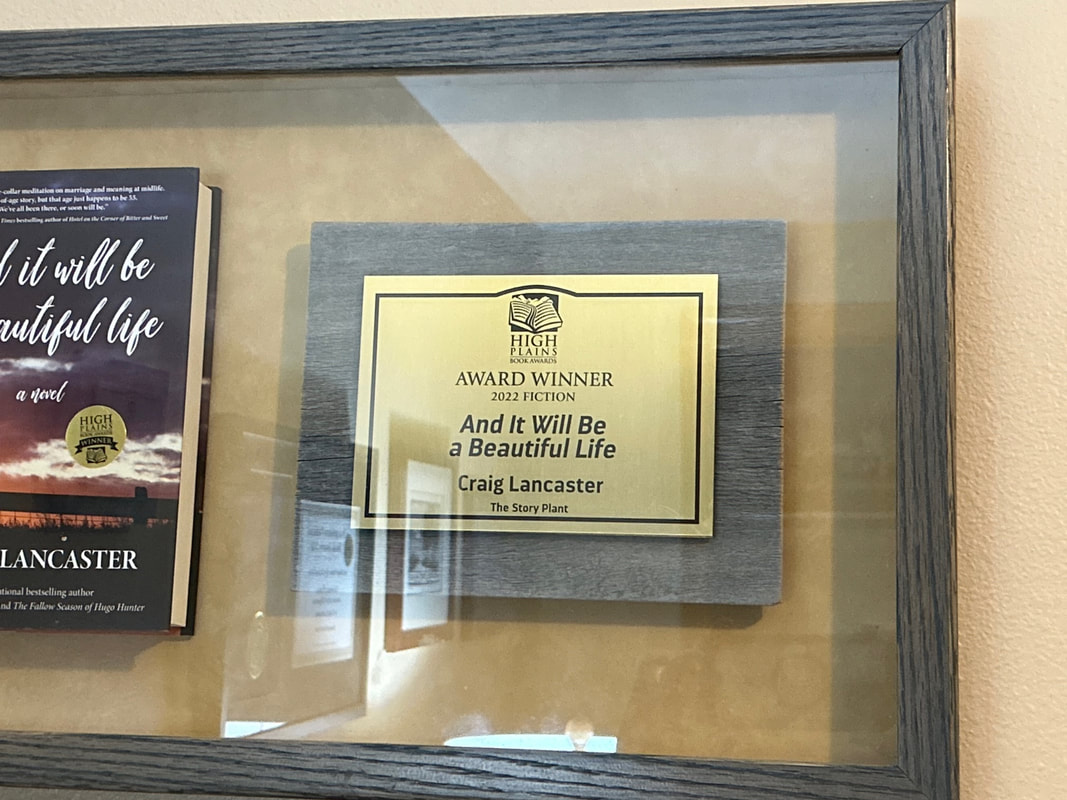

It's Saturday, October 7, and I'd much obliged if you'd hold a thought for the authors who have descended on Billings, Montana, this weekend. It was nearly a year ago to the day that I white-knuckled it through panel discussions and a lovely banquet, waiting to find out if And It Will Be a Beautiful Life had won the High Plains Book Award for fiction.

It had, which still fills me with wonder and gratitude.

A year has gone by, and 37 more books—spanning 13 categories—by some really terrific authors are up for consideration. In a short period, the High Plains awards have become among the most sought-after regional literary prizes in the country. It's quite an event and quite an honor.

Please send your best wishes to everyone who made it this far. 11/2/2022 0 Comments Launching ALL OF YOU

Now that the video is up at YouTube, I'd be grateful if you checked out this interview I did with my wife, Elisa Lorello, to mark the release of her new novel, All of You. I've been hoping for many, many years that I'd have a chance to get to know her better, so lucky me!

We get into a lot of stuff in a wide-ranging conversation (we really don't have any other kind). I'm just so proud of her and of this book, which is getting some rave reviews.

Want a signed copy? You can get it at our favorite bookstore, This House of Books in Billings, Montana. Just note in the comment box that you want it signed, and Elisa will oblige you. So, before I go off on a burst of happiness, I should do this: In the interest of consistency and intellectual rigor, I must adhere to my basic sense that happiness, as an emotional state of being, is highly overrated. It's too reliant on current circumstance to be trustworthy, and the factors that spur it—good news, fortuitous coincidences, pure serendipity, and the like—are too transient to be relied upon. My aim in saying this isn't to knock happiness—if you have it, brother or sister, be thankful for it and keep it as long as you're able—so much as it is to cast a vote for its more durable cousin, fulfillment. If you're fulfilled in where you are, whom you're with, what you're doing, where you're headed, you have something to hold tight to when the transience of happiness is with you and when it's against you. That's my theory, anyway. That said, I'm pretty (burbly-happy curse word) happy these days. Let me count the reasons ... 1. One night in Big SkyI'm just back from Big Sky, about three hours from where I live. The board of the Big Sky Community Library chose And It Will Be a Beautiful Life as the community read (One Book Big Sky) for the fall. Tuesday night was sort of the capstone of the event. I drove out, had a wonderful chat with folks who read the book, spent the night, and came home. It was a soul restorer in all the best ways. When writers and writers gather, it can be a lovely thing (see below), but it can also be a release of the pent-up frustration that only writers know and thus are in position to help each other through. When readers and writers gather, it's straight-up love. How lucky was I to spend an evening with a bunch of people who read my book, read it closely, had such interesting things to say about it, and wanted to come talk with me? The luckiest. No doubt about it. I rode those good feelings all the way home. The drive from Big Sky to Bozeman is one of the most visually arresting things you can see anywhere in these United States, so there's that, and believe me, I drank it in (figuratively). I made stops at libraries in Bozeman, Livingston, Big Timber, and Columbus, planting seeds for more days and nights like the one I'd just enjoyed. Here's hoping. 2. The blessings of good friends With AMERICAN ZION author Betsy Gaines Quammen. With AMERICAN ZION author Betsy Gaines Quammen. I think I'm only just now getting my considerable arms around how emotionally bereft the pandemic has left me (and so many other people, judging from what I'm reading and what I'm hearing). Honestly, I thought being chased inside and away from gatherings was a small blessing amid a horrible event, but it wasn't that at all. Now that I can see and meet the people I want to see and meet—while still being careful, of course—I'm realizing how much I craved it. Just in these past few weeks, I've gotten to hang in Butte, Missoula (thank you, Gwen Florio and Malcolm Brooks), Livingston (thank you, Amy Zanoni and Maggie Anderson), Bozeman (thank you, Betsy Gaines Quammen and Kryssa Marie Bowman), and Big Sky. I've had the fellowship of brilliant writers and thinkers, genuinely good people, and people who lovingly tend to the cultural life writ large. Man. I've needed that so much. So much. Happy? Yeah, I'm happy. But grateful most of all. 3. The work is going well Winning an American Fiction Award was a lovely bit of news to receive. Winning an American Fiction Award was a lovely bit of news to receive. OK, look, here's where I keep it honest: If my publisher had said, sorry, kid, but your manuscript stinks and I'd received a lot of hate mail and my dog was snubbing me, would I be Mr. Happy? I would not. This, of course, underscores my point about fulfillment vs. happiness. I work to a standard I set so I can know I've done my best regardless of what a gatekeeper says (or, at least, so I'll have the gumption to try again if I find the door closed). I try to approach the world with an open heart because I believe that's how we get past at least some of our divisions. I engage with my dog so he knows I'm his, and he's mine. That's fulfillment. The happiness of it comes and goes. But I can't deny that I'm really, really enjoying every side of the work right now: The creation of it, when it's just me and an idea and the challenge of getting from here to there. The production of it, where I interact with the publisher I wanted to be with and who wants my work on his list. The carrying it to readers and interacting with them, which can be such an incredible validation of the work put in. The awards, both realized and potential (talk about transience). I'm as energized for all of it, the whole arc, as I've ever been. In Missoula, while waiting to eat lunch, I happened upon a meeting with a well-regarded poet and fiction writer and a genuinely good human. I don't know him well, but I like him, and even so, in the worst of my do-I-want-this-anymore crisis a few years ago, I deleted him (and a whole lot of other writers) from my social contacts, in a clumsy, flailing attempt at ridding myself of reminders of an endeavor I wasn't sure I wanted anymore. So there I was in Missoula, nonexistent hat in hand, apologizing for something I'm sure he didn't even notice, telling him I was in a dark place. He was kind and compassionate, as I expected he would be. I still appreciate the grace. I hope, the next time I'm on the other side of that conversation, I extend it to someone who needs it. I'd like to think I've learned something. Certainly, I appreciate that the want-to came back to me, and I'm going to nurture it as much as I can. But what happens when rejection arrives (as it surely will), or awards don't (ditto)? I don't know. I'll try to remember now and then and remind myself that I can be in both places. Just not at the same time. 3b. That was a lot. Here's an anecdote. So I'm driving home from Big Sky and I'm talking on the phone—hands-free—with Elisa and I'm saying much of what I said above, only differently, and I'm telling her how energized I am, and I'm hearing how energized she is, and we come around to You, Me & Mr. Blue Sky. It's the novel—a romantic comedy that goes deeper, as Elisa's work does—she and I wrote together in 2018 and 2019. We released it ourselves ... and pretty much let it flop around out there. Our crises of confidence coincided. Those were hard, broken days. We had no energy for much of anything, and certainly not for getting out and trying to introduce a book to the world. We were too adrift in our personal lives to have the fire for the professional. Frankly, there were times I wasn't sure we'd make it. But we did, and we have, and we're going to. Elisa is back, too, and she said, you know what, we should put a new jacket on that old novel we never really got behind. Freshen it up. It's a story of brightness and hope, and it has this dreary cover that doesn't fit it. Let's give it some love. OK, she didn't say that exactly, but that was the gist. And here it is, dressed to meet the readers we hoped it would meet. 4. Health Elisa didn't join me in Big Sky because our cat, Spatz, has been ailing. The most recent health issue was one that had a small sliver of hope for resolution and a rather wide, grim likelihood in terms of what we'd have to do. I had an appointment I had to keep, and Elisa decided to stay behind and tend to our girl. And our girl, not for the first time, has proved resilient. Her issue has resolved itself—or, at the very least, has recessed into a place where she's her old self again for however long that lasts. She was a surprise when she came into our lives, and we've resolved to enjoy her for as long as we have her. That horizon, delightfully, has widened. We're thrilled. As Elisa is given to saying, she's our Rushmore, Max. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed