|

My friend Caroline Patterson has a new novel coming out Sept. 15. It's titled The Stone Sister, and it promises to be an absorbing, fascinating read. It's getting some fantastic endorsements from the likes of Ann Patchett, Annick Smith, and Kim Zupan. Here's a book trailer: Looks fascinating, doesn't it? Well, go get it.

And while you're at it, be sure to check out Caroline's exquisite new website and learn more about her and her work.

0 Comments

8/29/2021 0 Comments A Few Words about 'The Word' Several years ago, I would rope my Facebook friends into this weekly crowdsourced writing project called "The Word." The exercise was not my invention. I lifted it from Janet Fitch after I'd read something from her about it, and it quickly became something I did both on my own time and on those rare occasions when I would lead a writing workshop. It's such a simple concept, full of creative potential: You solicit a single word, then proceed like so: That word inspires a short story that you're to write in a nominal amount of time (say, an hour), and the resulting story must include the word. It's so much fun to give a single word to a large group of writers—say, for example, a group of inmates at the Oregon State Prison, where I led a workshop several years ago—and see the wide diversity of what comes back. So every week for the better part of a year, I'd say something like this on Facebook: "Give me a word. Any word will do. Give it to me." I'd accept suggestions for an hour or so, run a random number generator, choose the corresponding word, then sit down and write. Below is an example of a resulting story, taken from my collection The Art of Departure. If I remember correctly, the word that prompted this one was "squab." It ended up taking quite the backseat in the story it inspired. PonziIn September of that year, our neighbor Wayne had this idea that he could get rich by selling groceries Amway-style, and he booted his twelve-year-old boy out of his own bedroom and put up shelves loaded with packages of spaghetti, cans of roast beef, soda pop by the case and other non-perishable goods. Soon after, Wayne came over to our house and gave my folks the pitch, showed them how, if they just signed up a few friends and those friends signed up a few friends, and so on, they could make as much as $10 million a month, all by making a little bit on every transaction. “Everybody needs groceries,” Wayne said, mopping sweat off the folds of blubber on his neck. “It’s the perfect plan.” My pop liked Wayne, liked going out with him occasionally and tossing back some suds, and he paid the ten-dollar membership fee and accepted the tabbed folder that contained the list of goods and prices, as well as several pages of helpful hints for enrolling friends in the program. “We’ll see what we can do with it, Wayne,” Pop said, showing him to the door. “It’s an interesting idea you have here.” The old man had said something similar a few times before. We still had a shed full of cleaning chemicals that Wayne had foisted on Pop in an earlier scheme. The stuff was supposed to get rid of deep grime on contact, and sure enough, it performed as advertised. It also ate a hole in our carpet. Pop put the stuff in the storage shed because, I think, he didn’t quite know how to dispose of it, and he didn’t want to hurt Wayne’s feelings. A similar sensibility had driven him to sneak out of the house one night and open the door to the pigeon coop Wayne had insisted he build. The next morning, the flock had flown away, and Pop went across the street and told Wayne that they wouldn’t be making that killing on squab. “You’re a soft touch, Leonard,” Mom scolded him, and Pop mumbled something about how it didn’t hurt anything. Mom often said that the old man “enabled” Wayne’s irresponsible behavior; most of Mom’s vocabulary came from the self-help books she consumed with the fervor of the newly touched religious. That idea never seemed to resonate with Pop. Mom thumbed through the folder. “This isn’t going to work.” “Why not?” Pop asked. “Seems like a decent idea. Like Wayne said, everybody needs groceries.” “Yeah, but look at this.” Mom thrust the folder at him. “Now just look at that: Cheer laundry detergent for $2.49. I can get it for a dollar less down at Skaggs. And $1.50 for a two-liter bottle of Coke? I got it for 99 cents yesterday!” It went on like that for another half-hour or so. After the first few broadsides by Mom against Wayne’s plan, Pop looked for an escape. He tuned in to the Texas Rangers game on the radio, while Mom sat at the kitchen table and lingered over the list of products and prices. Their interplay was a series of exclamations in one room and knob adjustments in the other. “Two-ninety-nine for Sanka!” Pop turned up the volume on the radio. “A buck eighty-nine for Doritos!” Pop flipped over to Bill Mack on WBAP. “A dollar-ten for a can of tuna!” The old man turned off the radio and went outside. “Rangers lost,” I said. I held open a lawn bag so Pop could scoop a load of early fallen leaves into it.

“Figures,” he said. I shook the bag to settle the leaves and then tied off the top. Pop fished his smokes from his front pocket and lit up. “I guess Wayne’s idea has a few flaws,” I said. “Guess so.” The old man exhaled a string of smoke from the side of his mouth, upwind of me. “You know, he kicked Ethan out of his own bedroom so he could put food in there.” Pop didn’t say anything, but I could see his jaws clench. He was chewing on something that was giving him trouble. Whatever it was, I knew I’d never hear about it. “Men sometimes lose their way, Jon.” He crushed the cigarette into the brick of the house, behind the hedge where no one would see the mark. “Come on,” he said. “It’s getting late.” 8/23/2021 15 Comments Jon Ehret, My BrotherNot that we’re back in eighth grade or anything, but in the couple of days that this thing has been sitting on my head, wanting to come out through my fingertips even as I had no idea how I would start it or where I would end it or what I would put in the middle of it—and, Jesus, now I’m quoting Seger, what to leave in, what to leave out—I’ve been thinking about a decidedly eighth-grade question: Who’s your best friend? Seriously, who? Is it your spouse, the person you spend the most time with, the person who hears and tolerates and rides out all the stupid shit you say, the person who’s in bed with you, who knows every embarrassing thing, who shares all the same things with you, who knows where the hurts and the hopes and the hesitations are? That would be a good answer, your spouse. In most considerations, yes, that’s absolutely the answer for me. Or is it your work confidant? Your childhood friend who has somehow endured? The high school classmate you didn’t know then but are connected with now and cannot imagine not knowing and loving? Your college roomie? Is it your neighbor, the person in the pew every Sunday at church, the father of your kid’s best friend? Or, maybe, is it someone who has rippled through your life, like a pebble sending slow-moving water rings to the shore? You had something going for a while, then life and distance intervened, then you picked it up and it was just as good as before—no, no, it was better—and then you set it down again, and then it came back one more time and it stuck for good. It has survived decades and losses and different cities and different sensibilities and different marriages and different jobs, and it’s the same thing it always was and it’s also something new, something evolving, something surprising and cherished. Couldn’t the person with whom you share all that be your best friend? Shouldn’t the person with whom you share all that be your best friend? Jon Ehret was my best friend. Jon Ehret is gone. How am I supposed to do this without him? Before I get into the various specific times and qualities and shared experiences that made Jon my friend, I need to answer broadly the question of why it worked for us, why we latched onto this friendship in the last decade of the previous century and saw it through for thirty years. No offense intended, but I don’t need to answer that question for you. The world can go on spinning if you don’t understand it, and while the world certainly will go on spinning if I don’t answer for me, here’s the deal: In hindsight, I can see it, all of it, what we shared and why it mattered and why it stuck. And hindsight is all I have, now. The drive Elisa and I never made to see him and Laura in their new house in Santa Fe, that’s not happening. His invitation for me to head down and meet him in Utah, where he was picking up a rescue bird (there will be more on this), the one I turned aside with “damn, my work schedule” and “invite me on the next one”—there won’t be a next one, and thus there will be no invitation. The last time I was in Buffalo, N.Y., his hometown (there will certainly be more on this), and invited him to fly out and he turned me aside with “damn, I’ll be at a wedding in Texas.” Yeah, that’s not happening, either. It’s all hindsight and memories and smart-ass ripostes on Facebook and a text thread on my phone that I will never erase, in hopes that I can someday bear to look at it again. That’s all there is. So here’s why it happened and why it mattered and why it stuck, and if this is too abstract, you’ll just have to trust me: Jon and I were the same but different, and this is the second time in a week I’ve used those words to describe the way I’m hard-bonded to someone. And because those bonds were so difficult for each of us to find with other people—there’s nothing like the unexpected death of your best friend to serve as a reminder that you make friends broadly but struggle to hold on to them deeply—we held tight to the fact that we found them with each other. I think we always knew what it was, but we took a long time to acknowledge it with a nod and longer still to say it and put wind under the words. We did, though. For that, I’m grateful. I have that, too, and so does he, wherever he’s off to. So, look, I should hope it doesn’t happen to you, but maybe it already has, and the longer you live, the greater the likelihood that it someday will. Your phone rings one bright day, and it’s Laura, and you know it when you hear her voice, because although you’ve known her for as long as you’ve known him, and you love her as much as you love him, he’s still the conduit by which the whole thing goes, and if she’s calling, that must mean Jon cannot, and so here it comes. This all occurs to you in a whisper of a fraction of a second. It’s fucking insane how fast and final it all is. Jon died at work, at the bird rescue center in New Mexico where he had found purpose in semi-retirement. He was in his joy, and then he was gone before his coworkers found him. Fifty-five years old. Heart attack, it would seem. No warning, no chance at intervention and another outcome. Gone. I spent the better part of a decade flat-out ignoring a condition that I knew would kill me if I let it. Jon had a lovely day with his wife, then went off to his birds, and never came home. We’re the same but different. Laura tells you all this, and you remember another phone call, 1993, Owensboro, Kentucky, to Buffalo, New York, and you were the one piercing the bright day and saying our friend, Brian, he’s dead, and Jon says, “Why?” And you realize that’s one hell of a good question, then and now, because it’s the only question you have: Why? Nobody fucking knows why. And you bounce to another memory, Brian and Jon at the center of it, where you’re at work as a sports clerk at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, couldn’t have been later than fall of 1991, and you’re making fun of your boss’ phone manner, because you’re 21 and a smartass, and you pick up a dead phone and say, “Staaaaar-TelegramsportsthisisEd,” because that’s how Ed says it, and all the editors on the desk are laughing, because you’re one funny sumbitch, and you don’t see Ed behind you and he says, “That’s pretty good. Good skill for your next job.” And here’s Brian: “I just got a warm feeling.” And here’s Jon: “That’s not a warm feeling. That’s Lancaster pissing himself.” And here you are, missing them. We met at the Star-Telegram. Jon was 24, and I was 20. He had a master’s degree from the University of Missouri in hand, and I was steadily on my way to bombing out of college for good. The same but different. He liked The Who and King Crimson. I liked Paul McCartney and R.E.M. I was making plans to move to Alaska (for the first time), and he thought that was the coolest thing in the world. I thought he was the smartest guy I knew, a brilliant layout man (we drew them in those days, kids) and someone worthy of emulation. We were big, lumbering guys, often more comfortable in our interior lives than we were on the outside. I covered up with a sort of zany bearing and kept a lot of my deeper thoughts to myself. Jon balanced anger and the most generous heart I've ever known. The same but different. Later, the connections went deeper. A weekend with the Ehrets after he and Laura moved to Buffalo, a day trip to Niagara Falls, an introduction to Newcastle Brown Ale, before it went all corporate. A snowy night, the last of the trip, when we ordered in and he urged me to get a cheeseburger sub and when I hesitated, he was all, “Man, it’s a cheeseburger on better bread. What’s the problem?” No problem at all. Delicious. And while we had surely eaten meals together before then, in my memories that’s the line of demarcation where shared food experiences became part of the deal: Jak’s in West Seattle, barbecue in Texas, seafood in Damariscotta, a legendary birthday meal at Walkers here in Billings on a minus-12-degree day, his urging me toward Ted’s Hot Dogs and Duff's in Buffalo, and my going to both, every time I'm there, even though we were never again there together, now much to my eternal regret. “Buffalo is a great fatboy town.” I say it. I live it. Jon said it first. In 1996, I decided, after some consideration, to seek out my birthmother. I told Jon what I was doing, because I knew Jon would have both an appreciation and a point of view, as an adoptee himself. He didn’t tell me not to, but he presented every you-oughtta-be-careful-here he could think of. He said he couldn’t imagine doing it. I did it anyway. Many years later, when he could imagine such a thing, I could give him some on-the-ground intel. I could validate the things he got right, contradict the ones he got wrong, and throw up flags around the ones neither of us thought of. He did it anyway. And, our being the same but different, we had more to talk about, in conversations that had the width and breadth and depth of galaxies. The kind we had so much difficulty having with other people and yet never had trouble getting into together. Another night of spotty sleep draws near, so let me just wrap it up this way:

I have four brothers in a family line that looks like a tangle of kudzu more than it does a tree. There’s the brother I inherited when my mother and my stepfather got together. We lost him four years ago. There’s another who was born to that union. And there are two half-brothers who came with the search for my birthmother, the one I pressed forward with despite Jon’s admonitions, just as he pressed forward later with his own quest and his own questions. Neither of us, I think, would turn aside the decision we made after it was done. The same but different. Then there’s the fifth brother, the one I chose, and the one who chose me. I know he’s my brother because he told me so, and because I told him so, and because he was the kind of guy who didn’t use words he didn’t intend, and he told me these a long time ago: If you ever need anything at all, you tell me, OK? I took him up on it, too, in ways that seemed picayune at the time and register even more inconsequentially now. I was lucky, I guess. I never needed anything substantial and life-changing. A kidney. A roof over my head. A slayer of the wolves at the door. You know, the biggies. A heart. He filled mine. He broke it, too, just the other day. I’ll patch it up. He lives there now. 8/11/2021 0 Comments The Trip That Wasn't

I shouldn't be sitting here typing these words.

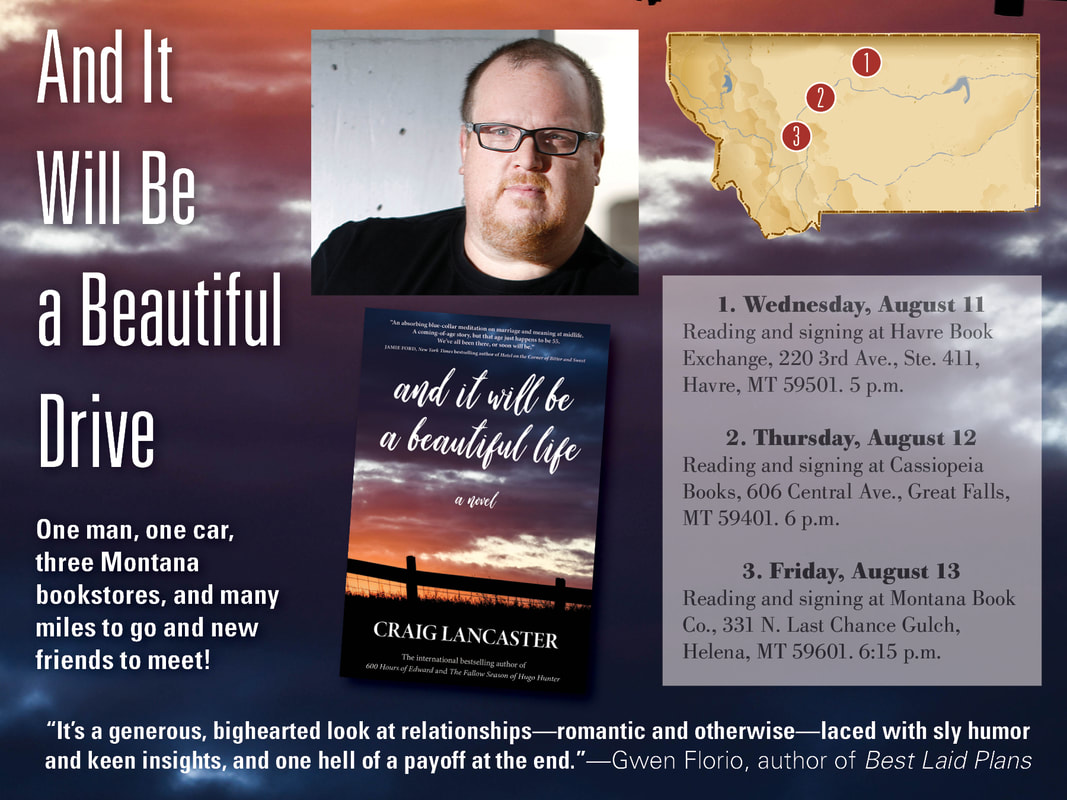

Were plans rock-solid, immutable things, I would be in my car right now, its nose pointed north, my pup Fretless in his bed in the backseat, on my way to a three-day adventure of meeting readers and introducing my new book to new friends. Plans, alas, are not rock-solid and immutable. They are, as Death Cab for Cutie noted*, "a tiny prayer to Father Time." I'll not be in Havre tonight and Great Falls tomorrow and Helena on Friday, making visits to these independent bookstores that I love. In two cases, it couldn't be helped. In one, it could be, but we—the collective we; remember that?—seem unwilling to do what's necessary, a problem that's far, far bigger than my picayune book event.  Fretless after Hospitalization No. 1. That's a good boy. Fretless after Hospitalization No. 1. That's a good boy.

Fretless took ill last week, leading to a frustrating series of escalating vet visits (and costs—oof). The poor little guy gave up first on food and then on water, and when his underlying bloodwork numbers and vital signs were otherwise pretty unremarkable, it all became this weird sort of Occam's Razor guessing game. At one point, the thinking was that he might have atypical Addison's disease (he doesn't, thankfully). Twice, the veterinarians pumped a liter of water into him. He has a pharmacy of meds lined up on the kitchen counter.

Finally, we found the culprit: pancreatitis, which is scary but treatable. He'll be fine. He's already well on his way to that, a welcome sight, but by the time we got our arms around the thing, I'd already canceled the gigs in Havre (Havre Book Exchange) and Great Falls (Cassiopeia Books). I hope we can reschedule, either later this fall with the hardcover or next spring when the paperback emerges. It's been years since I've been on the road with a book, and I was jonesing for this trip. Plans, man. They're tenuous things.

By the time I pulled the plug in Havre and Great Falls, the Helena trip (Montana Book Co.) was already off the board, a casualty of the spike in Delta variant cases. It's a completely understandable decision by the store. Believe me, no one wants live events more than bookstores do. As adaptable as they have all been to videoconferencing and trying to maintain community—the entire foundation upon which they are built—amid a pandemic, they know that there's nothing quite like an intimate gathering of people who love books.

But nothing is more important than safety. Please, get vaccinated. Wear your mask. Do it for others and for yourself. It's been far too long since we saw each other.

* — What Sarah Said

|

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed