|

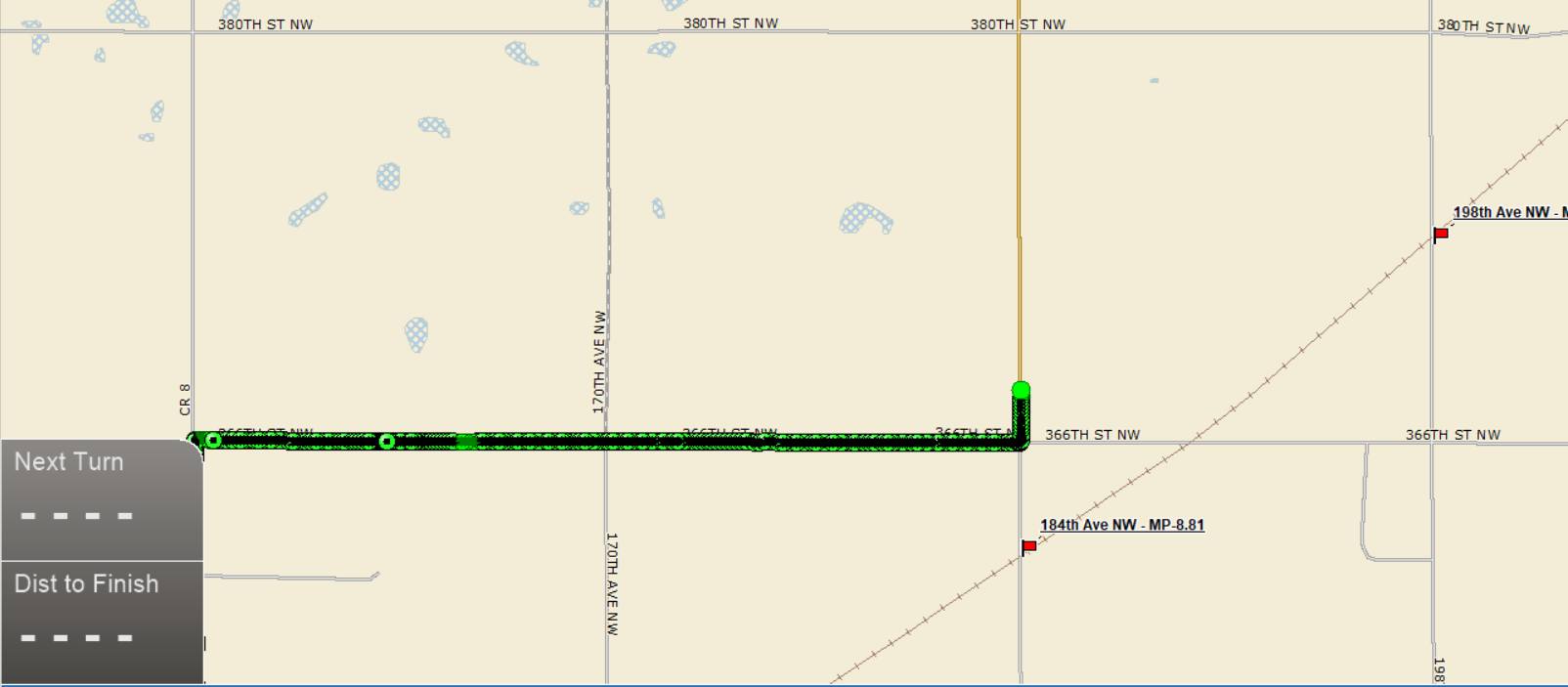

6/25/2022 2 Comments The Road Called, and We AnsweredHere we are, nearly halfway through 2022, and I've only just caught up to reconciling something that happened in late 2021. (I suspect this is either because I'm slow on the uptake or because I just hadn't taken the time to lean into my feelings and sort them out. Maybe even both!) At any rate, at the end of the year, the company for which I'd done some occasional pipeline inspection work for the past several years folded up its U.S. operations. Just like that, I was out of a gig. First, the important stuff: It wasn't more than a trickle of an income stream, so it's not like I was jobless or under the threat of imminent financial disaster. It wasn't and never had been a career, so I wasn't grappling with the loss of self. The point being, it wasn't a massive blow to the bottom line or self-identity. And yet ... It was a blow, undeniably. I felt the absence, and I felt a little unmoored by the fact that I didn't have any work trips coming up. I found myself thinking inordinately about the places I would commonly go on these work trips—Buffalo, N.Y., and Chelsea, Mich., and Michigan's Upper Peninsula, and the far reaches of Minnesota and Wisconsin. My thoughts would drift to Minot, N.D., where I'd gone for my first such job, way back in 2015. And then it occurred to me: What I'm really missing here is that liberating sense of being gone. I'm 52 years old, and I've never lost that urge toward motion, travel, getting in the car and going, any direction will do. I like hotels and corner restaurants. I like people watching in places where I don't know anyone. I like seeing what's over the next horizon, even if I've seen it before. By now, I surely most know that it's incurable. So I told my understanding wife that I needed to go, and I packed up the dog and a week's worth of clothes, and I went. The idea was to go to Minot and, from there, launch revisits of a few pipeline routes that emanate from there. The Minot part was easy enough. The rest, though, went against my expectations. Here's a glimpse (material stolen from a subsequent Facebook post):  See the orange post there? I tracked my first pipeline tool from that site (smack in Berthold, N.D.) back in 2015. See the orange post there? I tracked my first pipeline tool from that site (smack in Berthold, N.D.) back in 2015. I haven't missed the pipeline work—which, you know, is work—nearly as much as I've missed the travel and the solitude. The solitude most of all. I don't think happiness exists in a fixed place; it is, instead, what you make of it and where. But if I'm wrong about that and happiness really is out there in a place you can pin on a map, then I'm fairly certain that place is on a tertiary road in some lonely precinct where no one goes on vacation. I came here thinking I'd ride the full length of a few lines, stopping at every checkpoint and taking them in, and I was wrong about that. I don't need that much immersion. I just needed to be out. Away. Gone. Just for a few hours at a time. God, how I loved it. God, how I've missed it. On our last full day in North Dakota, Fretless and I rode a small portion of an 85-mile line that runs northwest from Berthold, N.D., to the Canadian border. It was, simultaneously, a total kick of nostalgia and an entirely new experience. The only time I did this line for real occurred in the deepest of winter, 2017. It was bitterly cold that night. The snow was in drifts. The wind blew the snow around in ways that would mess with your perception of things. On those dirt roads, some of them just two-track, you'd see a pile of snow and you'd stop the car and get out, the wind biting your face, and you'd walk it first to make sure you wouldn't get stuck. You don't want to get stuck, believe me. It's happened to me, more than once. It's bad. I once waited for seven hours in Wisconsin, my work vehicle sunk to its axles in a blizzard, for a tractor to come and yank me out. You don't want this. See the pipeline marker in the photo above. To do my job, I'd have to wade through snow, sometimes chest-deep, and put my sensory equipment there to record the tool passing by, deep underground. Then, after a passage, I'd have to wade back out and get the equipment, then try to swim back to the vehicle, hoping I didn't get hung up alone out there. Meanwhile, the tool was zipping along to the next checkpoint at about 7 mph, which is really hauling ass. It was desolately lonely and dark and cold and scary. I loved it so much. The line parallels railroad tracks (see the map above), which cross the road at uncontrolled intersections. In the night and the cold and the dark, snow flying sideways and obscuring your vision, you'd have to be careful, hanging out in those places. When Fretless and I went out, though, it was different. Warm and clear. Sunny. No snow. No drifts. More red-winged blackbirds than I could count, although not one of them stood still long enough for me to get a picture. Farmland was verdant with moisture, not gray and white and foreboding like in my memories. That night I ran the line for real, in March 2017, we finished at the border and the snow was coming down in massive clumps. I drove to my waiting hotel in Williston, more than 100 miles away, unable to see a damn thing, holding my phone in front of me and using the GPS program to keep my truck on the road, or where the road was supposed to be. I didn't tell my wife about that until a day later, when I was safely home. I don't miss that kind of stuff. A little more than a week ago, when I'd had enough, I asked Fretless, in the backseat, if he wanted to go back to the hotel. He wagged his tail agreeably. I cracked the windows, letting in some fresh air, and we got the hell out of there. It was glorious. Every little bit of it. I had to work the evening of getaway day, and long gone are the days when I can drive for eight hours and work for another eight, so we stayed that night in Sidney, Montana, another dot on the map rich with memories. Again, borrowing from Facebook:  See the windbreak there? That's on the southern edge of Fairview, Montana, a little town that straddles the Montana-North Dakota line. In late summer 1981, when my dad was in the midst of moving his drilling rig from one town to another, the right-front tire on his International Harvester Paystar 5000 blew out and he, with much effort, brought it to a stop right there. I have a clear memory of this because I was in the passenger seat, so it was my side of the truck that dipped precipitously, as if we were going to pitch over on our side. I also well remember it because it was a classic bad news-good news scenario. Bad for obvious reasons, and for these reasons: Dad's hired hands, who'd ordinarily be following him, had gone out ahead of us by a couple of hours. We were alone. Good because there's a house right there, and a small town just ahead. Easy to make a call, even in 1981, and get some help dispatched. Now, lemme ask you this: What do you suppose the percentage chance was that this boy, who lived at the time in Texas, 26 years later would marry a woman from tiny Fairview (population now 900, but much smaller then)? As it turned out, 100 percent. (We divorced seven years later, so it's less a fairy tale than an interesting coincidence. But still.) OK, let's move a dozen miles down the road to Sidney. That train engine, in Veterans Memorial Park, with Fretless offered for scale? I climbed all over that thing that summer. I was 11 years old, and that's pretty much the recreation that was available to me. The city fathers hadn't yet fenced it off, so I was free to clamber wherever I could get to. I also chewed illicit tobacco, given to me by my dad's helpers, who encouraged me to have all I wanted, knowing full well what would happen to me. Bastards. Anyway. Across the street, still standing but no longer operational, it seems, was the Park Place Motel. I lived that summer in one of the bottom-floor rooms, with dad and his wife. It was entirely too cozy, entirely too stifling, entirely too familiar. And yet, I'm thankful for the memories, which quite without my realizing it were becoming fodder and fuel. I've set stories in that park, and in those fields beyond it. With very little disguise (or even much of a name change), I've turned Fairview into a character all its own, the little town of Grandview in This Is What I Want.

It's all been a gift, every bit of it. I'm grateful, all the time. And I can't wait for the next trip ...

2 Comments

6/10/2021 0 Comments Darrin. Originally published January 7, 2021 There’s no clever way to start this, and from the vantage point of these scant words, I feel as though there’s only one place to end it: with anger. Which sucks. Darrin Marie Murdoch is dead. As I sit writing this—on Christmas Eve, for publication in a couple of weeks—she’s been dead for four months and ten days. I’ve known for the ten days. That’s it. And I’m pissed, mostly that Darrin was plucked from this life when she was so young and so loved and so needed (which I’ll get to soon), but partly because I didn’t know she was gone until a succession of thoughts came to me: 1. I haven’t seen updates from Darrin in a while. Facebook and its confounded algorithms are hiding her from me. 2. I’ll visit her page. 3. Oh, god, no. I could castigate myself for not seeing her obituary in the newspaper or online. I could lash out at our common friends who did know she was gone and didn’t tell me. (I could do it, but I would be wrong and I would be unkind.) I blame the pandemic. Not for taking her, because that doesn’t appear to be the case. She’d had a host of health difficulties and a recent surgery, and she went to sleep one night and didn’t wake up on the other side of it. This is life and the bargain that comes with it. You gulp in that first big breath, then you start playing your time against a clock that stops at some indeterminate hour. I get all that. What I don’t get, and what I’m continually angry about in a universal sense, is why it had to be this way. Those of us who have acted responsibly (and aren’t frontline health care professionals or essential workers) have gone into our silos for nine months and counting while the government fails all of us and while we fail each other with selfishness and a miscast notion that freedom can stand independent of responsibility. Our lives have gotten smaller, if indeed we’re fortunate enough to have hung on to them at all. In the house my wife and I share, we wake up, we have breakfast, we split up for work, we reconvene periodically throughout the day, we climb into bed, and we do it all again. We have each other and our pets, and that’s a lot, but it’s also not nearly enough. Meanwhile, in the larger sense of this country’s collective COVID-19 failure, we’re all losing what binds us even as we’re inured to the loss. It feels as though, on the other side of this, we owe each other forgiveness for the things we have and haven’t said and the things both done and undone. I feel the weight of the penance I need to do, the amends I must make, and the grace I need to offer. I also feel the burden of anger that lights up and burns like flash paper. How does anyone balance all of that? In April, just a couple of weeks after we arrived back in Montana after a nearly two-year sojourn in Maine, I wrote these words for an anthology called Stop the World: Snapshots from a Pandemic. They felt visceral then. They feel something else now, in retrospect—hopeless even as the vaccines roll out (amid one final failure from the outgoing administration), sadly outdated in the death toll, and prescient in a way I never wanted to be: We’re alive, if not entirely living as we once thought of it, while we wait for something resembling normalcy to return. As I put down these words, the U.S. death toll has crossed 50,000, a number surely to rise. Only in the awful solitude of my imagination do I dare consider what it might be before these words find your eyes. I don’t want to know. But I’m going to. If I live to see the final toll. If I’m lucky. The word lucky has never been so perverse. If you’ll forgive the coldly corporate nomenclature, COVID-19 has a cost structure, and the tolls seem random: Some pay with isolation. Some pay with inconvenience. Some pay with sickness followed by recovery. Many millions have paid with their jobs. Tens of thousands, so far, have paid with their lives in the U.S. Worldwide, it’s hundreds of thousands more. The only bitterly sure thing is that we’re all paying with something. I was supposed to see Darrin again. Surely, in a normal set of circumstances, I’d have seen her between April and August. Failing that, surely, in a time unencumbered by social distancing and voluntary withdrawal, I’d have been engaged with our shared social structure enough to know she had gone. I would have been at her funeral. I would have hugged her mother, who has lost all of her children these past few years. I would have said goodbye instead of oh, god, I didn’t even know you were gone. This is part of the toll. Darrin was a teacher*. She loved those children with her whole heart. She especially loved the poorest of them, the most neglected, the ones with the biggest hurdles to overcome at the youngest ages. She believed in them, and for that reason more than any other, she should have lived forever. She was also fun, and smart, and bawdy, and loud, and loved. Every time she saw me--every time—I got a chaste kiss on the cheek. For several years, I had a standing invitation to her book club’s Christmas party, an annual date I hope will be renewed when we can gather again, although in the next beat I wonder how it can go on without her. Nobody loved the food or the drink more than she did. Nobody was more willing to say what she really thought of that month’s book than she was. (I know this firsthand, having a memory of this exchange: “Listen, your last book didn’t have an ending.” “Yeah, it did.” “Craig, no, it didn’t.”) Goddammit. I should have had time to tell her she was right about that. *If, like me, you believe that public schools and public education are worth fighting for, and that teachers like Darrin Murdoch stand between the rest of us and the wolves at the door, I implore you to offer a gift to the Education Foundation for Billings Public Schools in the name of Darrin Marie Murdoch. Thank you for considering it. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed