|

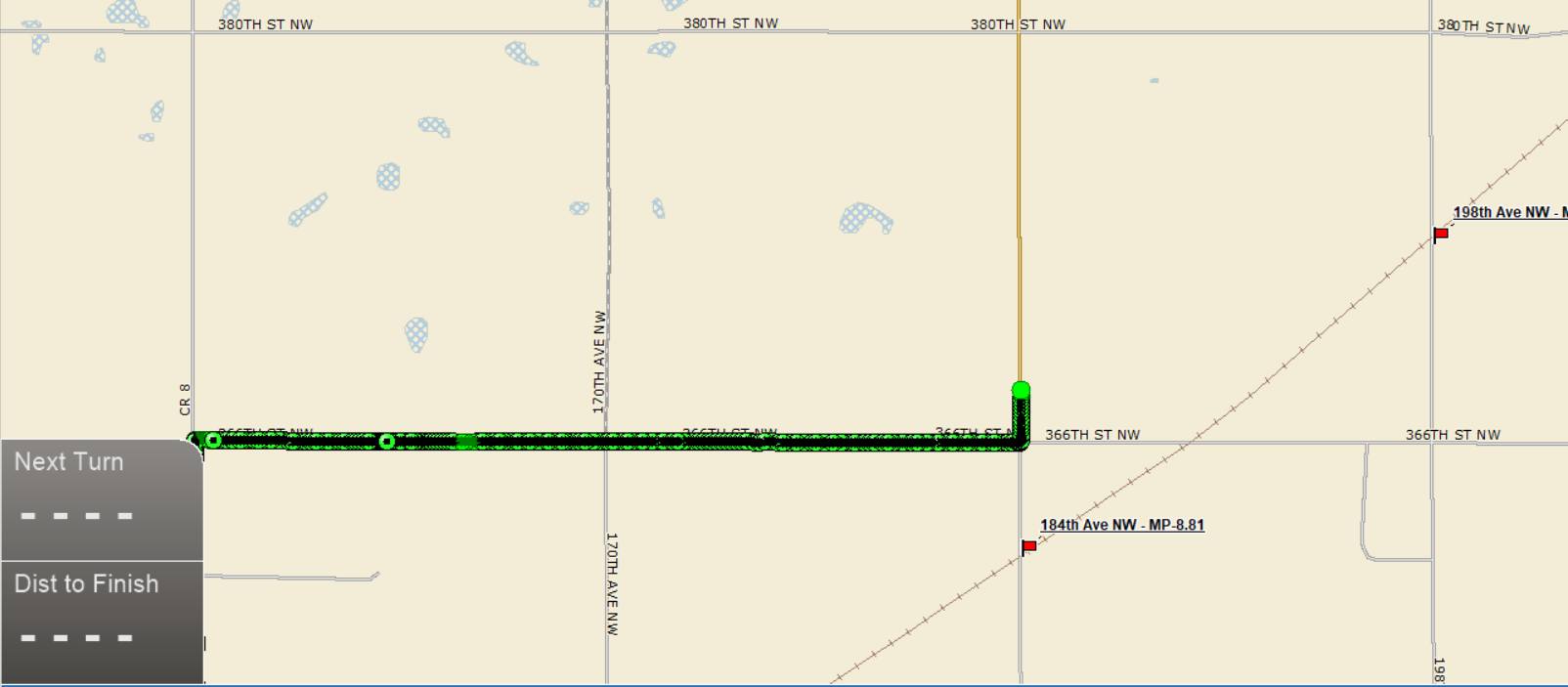

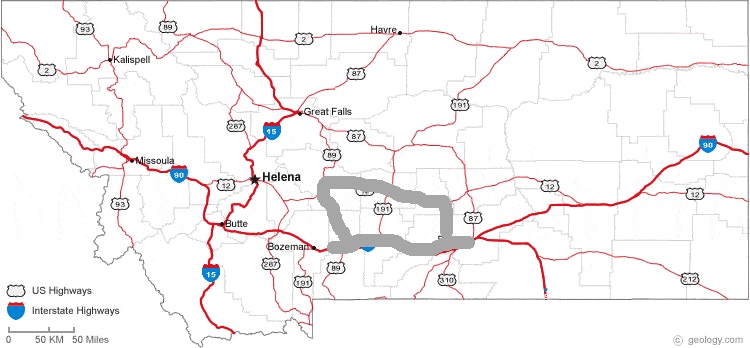

6/25/2022 2 Comments The Road Called, and We AnsweredHere we are, nearly halfway through 2022, and I've only just caught up to reconciling something that happened in late 2021. (I suspect this is either because I'm slow on the uptake or because I just hadn't taken the time to lean into my feelings and sort them out. Maybe even both!) At any rate, at the end of the year, the company for which I'd done some occasional pipeline inspection work for the past several years folded up its U.S. operations. Just like that, I was out of a gig. First, the important stuff: It wasn't more than a trickle of an income stream, so it's not like I was jobless or under the threat of imminent financial disaster. It wasn't and never had been a career, so I wasn't grappling with the loss of self. The point being, it wasn't a massive blow to the bottom line or self-identity. And yet ... It was a blow, undeniably. I felt the absence, and I felt a little unmoored by the fact that I didn't have any work trips coming up. I found myself thinking inordinately about the places I would commonly go on these work trips—Buffalo, N.Y., and Chelsea, Mich., and Michigan's Upper Peninsula, and the far reaches of Minnesota and Wisconsin. My thoughts would drift to Minot, N.D., where I'd gone for my first such job, way back in 2015. And then it occurred to me: What I'm really missing here is that liberating sense of being gone. I'm 52 years old, and I've never lost that urge toward motion, travel, getting in the car and going, any direction will do. I like hotels and corner restaurants. I like people watching in places where I don't know anyone. I like seeing what's over the next horizon, even if I've seen it before. By now, I surely most know that it's incurable. So I told my understanding wife that I needed to go, and I packed up the dog and a week's worth of clothes, and I went. The idea was to go to Minot and, from there, launch revisits of a few pipeline routes that emanate from there. The Minot part was easy enough. The rest, though, went against my expectations. Here's a glimpse (material stolen from a subsequent Facebook post):  See the orange post there? I tracked my first pipeline tool from that site (smack in Berthold, N.D.) back in 2015. See the orange post there? I tracked my first pipeline tool from that site (smack in Berthold, N.D.) back in 2015. I haven't missed the pipeline work—which, you know, is work—nearly as much as I've missed the travel and the solitude. The solitude most of all. I don't think happiness exists in a fixed place; it is, instead, what you make of it and where. But if I'm wrong about that and happiness really is out there in a place you can pin on a map, then I'm fairly certain that place is on a tertiary road in some lonely precinct where no one goes on vacation. I came here thinking I'd ride the full length of a few lines, stopping at every checkpoint and taking them in, and I was wrong about that. I don't need that much immersion. I just needed to be out. Away. Gone. Just for a few hours at a time. God, how I loved it. God, how I've missed it. On our last full day in North Dakota, Fretless and I rode a small portion of an 85-mile line that runs northwest from Berthold, N.D., to the Canadian border. It was, simultaneously, a total kick of nostalgia and an entirely new experience. The only time I did this line for real occurred in the deepest of winter, 2017. It was bitterly cold that night. The snow was in drifts. The wind blew the snow around in ways that would mess with your perception of things. On those dirt roads, some of them just two-track, you'd see a pile of snow and you'd stop the car and get out, the wind biting your face, and you'd walk it first to make sure you wouldn't get stuck. You don't want to get stuck, believe me. It's happened to me, more than once. It's bad. I once waited for seven hours in Wisconsin, my work vehicle sunk to its axles in a blizzard, for a tractor to come and yank me out. You don't want this. See the pipeline marker in the photo above. To do my job, I'd have to wade through snow, sometimes chest-deep, and put my sensory equipment there to record the tool passing by, deep underground. Then, after a passage, I'd have to wade back out and get the equipment, then try to swim back to the vehicle, hoping I didn't get hung up alone out there. Meanwhile, the tool was zipping along to the next checkpoint at about 7 mph, which is really hauling ass. It was desolately lonely and dark and cold and scary. I loved it so much. The line parallels railroad tracks (see the map above), which cross the road at uncontrolled intersections. In the night and the cold and the dark, snow flying sideways and obscuring your vision, you'd have to be careful, hanging out in those places. When Fretless and I went out, though, it was different. Warm and clear. Sunny. No snow. No drifts. More red-winged blackbirds than I could count, although not one of them stood still long enough for me to get a picture. Farmland was verdant with moisture, not gray and white and foreboding like in my memories. That night I ran the line for real, in March 2017, we finished at the border and the snow was coming down in massive clumps. I drove to my waiting hotel in Williston, more than 100 miles away, unable to see a damn thing, holding my phone in front of me and using the GPS program to keep my truck on the road, or where the road was supposed to be. I didn't tell my wife about that until a day later, when I was safely home. I don't miss that kind of stuff. A little more than a week ago, when I'd had enough, I asked Fretless, in the backseat, if he wanted to go back to the hotel. He wagged his tail agreeably. I cracked the windows, letting in some fresh air, and we got the hell out of there. It was glorious. Every little bit of it. I had to work the evening of getaway day, and long gone are the days when I can drive for eight hours and work for another eight, so we stayed that night in Sidney, Montana, another dot on the map rich with memories. Again, borrowing from Facebook:  See the windbreak there? That's on the southern edge of Fairview, Montana, a little town that straddles the Montana-North Dakota line. In late summer 1981, when my dad was in the midst of moving his drilling rig from one town to another, the right-front tire on his International Harvester Paystar 5000 blew out and he, with much effort, brought it to a stop right there. I have a clear memory of this because I was in the passenger seat, so it was my side of the truck that dipped precipitously, as if we were going to pitch over on our side. I also well remember it because it was a classic bad news-good news scenario. Bad for obvious reasons, and for these reasons: Dad's hired hands, who'd ordinarily be following him, had gone out ahead of us by a couple of hours. We were alone. Good because there's a house right there, and a small town just ahead. Easy to make a call, even in 1981, and get some help dispatched. Now, lemme ask you this: What do you suppose the percentage chance was that this boy, who lived at the time in Texas, 26 years later would marry a woman from tiny Fairview (population now 900, but much smaller then)? As it turned out, 100 percent. (We divorced seven years later, so it's less a fairy tale than an interesting coincidence. But still.) OK, let's move a dozen miles down the road to Sidney. That train engine, in Veterans Memorial Park, with Fretless offered for scale? I climbed all over that thing that summer. I was 11 years old, and that's pretty much the recreation that was available to me. The city fathers hadn't yet fenced it off, so I was free to clamber wherever I could get to. I also chewed illicit tobacco, given to me by my dad's helpers, who encouraged me to have all I wanted, knowing full well what would happen to me. Bastards. Anyway. Across the street, still standing but no longer operational, it seems, was the Park Place Motel. I lived that summer in one of the bottom-floor rooms, with dad and his wife. It was entirely too cozy, entirely too stifling, entirely too familiar. And yet, I'm thankful for the memories, which quite without my realizing it were becoming fodder and fuel. I've set stories in that park, and in those fields beyond it. With very little disguise (or even much of a name change), I've turned Fairview into a character all its own, the little town of Grandview in This Is What I Want.

It's all been a gift, every bit of it. I'm grateful, all the time. And I can't wait for the next trip ...

2 Comments

6/18/2022 0 Comments Scenes from a GetawayWords from the getaway—four days in North Dakota and the edge of Montana—to follow ... soonish. For now, enjoy the pictures!

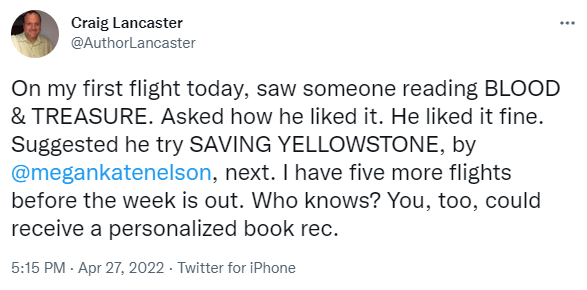

5/20/2022 0 Comments History as I Wish I'd Learned It Several months ago, one of my journalism and writing heroes, Tom Zoellner, invited me to review Saving Yellowstone for the Los Angeles Review of Books. I was a bit cowed by the prospect, to be perfectly honest. I don't have any standing, in senses literary or academic, to critique the work of Dr. Megan Kate Nelson, the book's author. I hadn't yet read her previous book, The Three-Cornered War, which had been a Pulitzer finalist. I was, upon first consideration, well out of my depth and not particularly inclined to take on the assignment. And then I reconsidered. If Dr. Nelson's literary ambition is to peel back history and explain it to a general audience—as well seems to be the case—then I'm about as general as they come. I'm curious and informed, I live in the region where the events of Dr. Nelson's book unfolded, and I try to live my ideal that an engaged life and mind require making some inroads into all you don't know (a considerable pile for me) and challenging those things you think you do know (also a considerable pile). In those ways, I was redeemed by reading and reviewing Saving Yellowstone—and by backtracking to read The Three-Cornered War. The review speaks for itself, I think. Beyond the completion of my assignment, the book has stayed with me. I've repeatedly recommended it, in sometimes obnoxious ways (see the tweet below). I've put it in the hands of friends. I've pondered the way Dr. Nelson's presentation of history—as something connected, something that breathes and reverberates—stands at odds with the lessons of the garden-variety public education I received in my Texas suburb, in which events were stand-alones and dates were to be memorized and regurgitated. Dr. Nelson's book details the Hayden expedition into Yellowstone, yes, and the establishment of our first national park, but also so much more, including the influences of capitalism, the literal and figurative erasure of Indigenous peoples, how the grappling with Reconstruction was not just a southern story but also a western one. One of the jarring lessons of the read, for me, was seeing the way the Grant administration's attempt to bring freed slaves into the body politic lay parallel with a policy of dispossession and extermination of Indigenous peoples in the West. The aims of the former policy largely failed; the aims of the latter were vastly realized. The result of both has been lasting inequality. The book is a triumph of dot connecting, of context, of presenting the bigger picture that lies outside conventional framing. It cannot be read without the realization that the fracture points of yesterday linger today. In the reading, I was reminded of something I often impart to editing clients when I sense that their narrative has gone passive (something that is NOT an issue for the history Dr. Nelson illuminates or the way she goes about telling it). The "and then, and then, and then" structure of storytelling will not compel an audience's attention or investment. I mentioned the polished-up version of history I absorbed and spat out for tests in my youth. That's how it was often (not always, but often) presented to me: Here's this. Here's this. Here's another thing. Here's still another. Hey, why is your head down and what's with all the drooling? Dr. Nelson's book, a work of scholarship, clicks along the way good storytelling does. It has sinew and electricity and a heaping measure of "but therefore ..." It moves. It speaks. It is kinetic. You must read this book. Yesterday, I drove from Billings to Livingston to see a lecture by Dr. Nelson and by Dr. Shane Doyle, who detailed the fascinating history of Indigenous peoples in Yellowstone.

Their presentations were sponsored by Elk River Arts & Lectures and the Park County Environmental Council and served as a fundraiser for the All-Nations Teepee Village, an event "to honor and recognize the many Tribal Nations with connections to Yellowstone and highlight the indigeneity of the landscape." To learn more about that effort (and to donate), go here, please. I've been in Montana for a while now--much longer in my heart than in my physical presence—and every day that has included a trip to Livingston can be filed away under the heading of "Best Days." Beers and yuks with the great Scott McMillion (who wrote the quintessential Livingston appreciation). A quick bite and more imbibing with Marc Beaudin. Chatting with Elise Atchison and Max Hjortsberg and Tandy Miles Riddle. Seeing pals on almost every corner. May your life be blessed with interesting travel and good friends. 3/30/2022 0 Comments EmergingLike many people, I've come to loathe Facebook in as many ways as I find it an indispensable means of keeping up with close friends and loved ones. Perhaps it's the indispensability that I loathe most. I also post things there deliberately, knowing that I'll be shown them again, year after year, so I can remember certain days with some degree of precision. Two years ago, March 30 was just such an occasion. On this day in 2020, the moving trucks showed up at our house in Boothbay, Maine, and whisked away our stuff. By then, it wasn't even our house anymore; we had closed on its sale a few days earlier and were just extremely short-term renters. We loved that house. We liked Maine. But neither love nor like was enough to hold us. That's old ground that needn't be gone over again. What's hard to remember now, even two short years later, is just how frightening the whole thing was. The world had closed up. We had moving guys tromping through the house, and we—Elisa, me, the dog, the cat, my dad, his dog—kept our distance and hoped they weren't sick. Hoped we weren't sick. Wouldn't be entirely sure how to know if we were or they were. There was a lot of taking things on faith. There was a lot of handwashing and surface disinfecting. There was a lot of uncertainty about what awaited us on the road. That first night, we stayed at a hotel in Portland. I, wearing rubber gloves and a paper mask, fetched dinner for everyone and brought it back to the two rooms (guys and dogs in one, woman and cat in another). Same drill for the subsequent nights, in Buffalo and Chicago and Minneapolis and Bismarck. We limited our points of contact. I did all the gassing up for the two cars, which were similarly subdivided with occupants. I wrangled all the meals, meeting Doordash and Uber Eats in hotel lobbies. In the East, where the pandemic initially hit hardest, we stared in wonder at empty turnpikes and rest stops. The farther west we drove, the more lax people seemed about what was happening. In Janesville, Wisconsin, I turned on my heel and left a store after seeing scores of unmasked people there. In North Dakota, a convenience store clerk poked fun at my mask. In Ohio, I asked a guy to move down a urinal, and he reacted with anger: "I'm not sick." "Fine," I said, "but maybe I am." When we got to Billings, it was more of the same. We were diligent, about our hands and our faces and our surfaces. We were scared. We sequestered ourselves away for two weeks and hoped we wouldn't get sick. The unknown was a menace. We weren't alone in feeling that. It's two years hence. We're just back from a two-week vacation. We saw loved ones. We hugged old friends. We gathered with thousands in a sports arena in downtown Dallas. We crowded into a banquet hall and said goodbye to a friend. The pandemic remains with us, of course, but it's different now, too. We're vaxxed and boosted, and soon to be boosted again. In recent weeks, we've begun stepping out again. Our first sitdown meal in a restaurant happened a few weeks before we traveled to Texas. Our first evenings out to see plays (masked), too. We carry the vax cards and the masks, in case they're needed. I imagine I'll wear one forevermore in airplanes and on trains and in crowded supermarkets. I'm cool with that. It's not a burden. We've been through two flu seasons now without the flu, a first for either of us. Credit the masks. Our doctor surely does. And yet, with the specter of omicron and whatever new variants might emerge, we worry about a scratchy throat or some mild congestion. Just the other day, we broke out a test for Elisa, who was feeling a little poorly. Negative. We've been lucky. No doubt about that. But we've also been diligent. We'll try to stay so, even as we dip further into what used to be normal life. The point of all this? There is no point, really. Gratitude. Caution.

We've had a hard two years, all of us. We've lost people we shouldn't have lost. We've grown isolated and angry. We've missed things we shouldn't have missed. May we find grace. May we offer it, too. 11/13/2021 0 Comments Odds and endsDispatches from the staying-in-touch department ...

Will the pig run again? I've written before about my occasional life in pipeline inspection — an association that inspired an entire novel — and had been looking forward to getting out there again in the spring, after the usual wintertime slowdown. Well, maybe, but also looking like probably not. The company for which I did work recently shuttered, and there's an industrywide slowdown, so I may be on the obsolescence end of progress (or regress). I can't say I'm particularly heartbroken. Pipelines are a destructive, invasive way of delivering extractive sources of energy, and for the future of the planet, it's high time we develop alternatives that are well within our grasp but beyond our political will. On the other hand, there's a practical consideration: We already have the damn things, and we're using them. The job I did was essential to the safety end of matters. Let's hope that continues until we can pull those things out of the ground and return the land to those from whom it was stolen. I will miss the travel to exotic (read: remote) locales and the chance to meet people in their natural habitat. But that can be enjoined in other ways, obviously. Union strong I recently did something I should have done a long, long time ago: I joined the Authors Guild. So here's where I cop to self-interest: I began to consider the possibility earlier this year when, quite apart from any involvement from me, my former agency descended into founder-vs.-founder contretemps and my meager royalties from long-ago books started showing up late or not at all. My former agent, also caught in the crossfire as her old shop melted down, was a champion and an ardent defender of my rights, it should be pointed out, and she got my situation squared away, for which I'm eternally grateful. But it occurred to me—again, when my self-interest was compromised, an entirely human condition that I'm trying to rise above—that in this whole solitary business, you have to grab a little solidarity where you can get it and stand strong with those who do what you do. I'm also reminded of something wise I once heard said by A.W. Gray, a well-regarded crime novelist but better known to me as the father of my boyhood best friend: "The people who need unions the most are those who don't have them." 9/24/2021 5 Comments Back to the Fork in the RoadIt's Sunday, September 19, and I'm on Interstate 25 in Casper, the nose of my car pointed north, toward home, a few hours away. I'm tired. My dog, Fretless, lies languidly in the passenger seat. He's had enough after a week away. So have I. Home, my wife, the cat—they all await. We have plenty of gas, had a bite to eat back in Douglas, fifty miles behind us. We have everything we need. The smart play is to get beyond this oil town and open up the cruise control a bit, see what this Toyota can do as we zip back into the emptiness of Wyoming and, eventually, get pulled into the embrace of Montana. So, of course, I exit the interstate, pick my way through downtown Casper, find CY Avenue—I once called it, in a novel, "the spine of the Casper grid system," which may or may not be true—and follow its familiar path to where I turn off for Mills, a little town north of Casper, and as I do, the well-trod memories come at me again. What I've come to see has been seen before, many times, and is likely to be seen many times yet, and if this particular side trip is taken as evidence that my life is in reruns, I will say only this in disputing that notion: Context is important, in all things and especially in this: I find it instructive, or at least perspective-granting, to be reminded of the life I might have had so I can better appreciate the one I'm swimming through. It's Friday, September 24, the day I'm writing this, and I'm reflecting on a spontaneous turn in a phone conversation with my mother this morning as we talked about other things. We talked, quite organically, about a decision she made for both of us in 1973, my third year. I was a capable kid, even at that age, blessed with an ability to carry on conversations with adults, but this matter was beyond my perception. She didn't want to live in Mills, Wyoming, anymore. That was surely half of it. The other half was that she didn't want me to live in Mills, Wyoming, anymore. She looked at the present, our life with my father there and what it seemingly held for us, and she projected out her future and mine and didn't like where those lives seemed likely to end up, and she did something about it. She took us out of there, into life with a man she'd met that year, the brother of her best friend, a man who lived in Euless, Texas. Not that it's anyone's business, but they hadn't had an affair. They'd had a connection, a chance meeting at a party that turned into a deep conversation that blossomed into a friendship and has become a nearly 48-year marriage. We talked about it this morning, Mom and I, this decision that with each passing year strikes me as more and more brave, more and more essential to both of us (and now to so many others—generations of others), more and more the line of demarcation, in strictly selfish terms for me, between where my life was pointed and where it ended up. I can see now, when I'm more than two decades older than she was then, how much gumption it required for her to do what she did. She was alone there, much of the time. She was 28 years old, and while Dad might not have represented maturity or loving or grace (I love the man, but let's be honest about the limitations), our prospects there were much more certain than they were anywhere else. There was a home well on its way to being paid off, an ascendant business, money in the bank. It would have been all too easy to stay. Many people have stayed for less. Mom saw the future and she left. I'll never receive a finer gift. So, you see, Mills, Wyoming, is actually a bit player in this what-might-have-been contemplation. It wasn't Mills we were escaping so much as who was there and what our life was there. It could have happened in Moline or Schenectady or Topeka. Could have, but didn't. This is, at its heart, a human story, a story of a boy with three parents who've imprinted him in wildly varying ways. I love my father, a love that shines through my struggles to understand him and his to understand me. It's a love strong enough to withstand my suspicion that my start in life would have been less than it was had I finished my growing-up years in his house. The math of that situation is inconceivable to me, given the way it all went. It would have been Mom and me in some kind of alignment agaInst the gravity of the way he is, the work that was always taking him away from us, and the instability of the home we were living in. I'm certain Mom's decision all those years ago hurt him. I'm also certain, if Dad can access clarity and honesty, that he'd say it needed to happen. For all of us. And what can a boy like me say about his mother that hasn't been said in better ways by better thinkers? She is pure love when it comes to her children and her children's children, but to leave it at that misses the fullness of who she is. At an age that seems to me, now, to be impossibly young, she was relentlessly wise. She had aspirations for herself (and has them still). To my ongoing gratitude, she could see a time coming when her son would have them, too. In so doing, she brought me into the sphere of the man who became my stepfather. Back then, he was a 31-year-old sportswriter at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, a man who had his own broken first marriage, a son, and regrets. He also had a shared hope with Mom that they could make a go of it together. I can scarcely remember a time before his presence in my life, and he has never, not once, treated me as anything but his own. That has made all the difference. I go back to Mills to remind myself that it could all have gone another way. Could have, but didn't. So what do I make of Mills, all these years later?

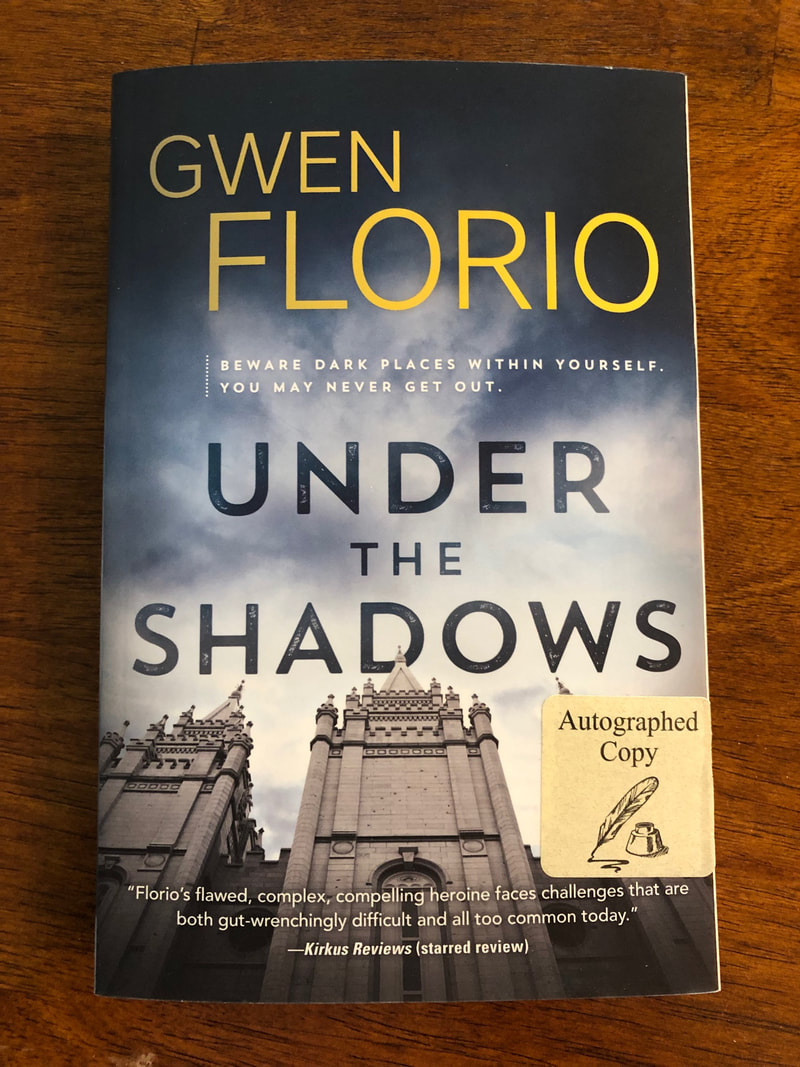

I think it would be presumptuous of me to make anything of it beyond my sliver of experience there. It's steeped in nostalgia and memories and wonder. Its presence on the outskirts of my life has been a professional gift, surely (the old memory + imagination thing), as well as fodder for the occasional facile joke. (One could certainly quip about "welcome to Mills, please set your watch back 20 years" or wax irreverent about how hard the wind blows there.) The thing is, I've lived enough places and known enough people to realize something important: Most anyplace can be home, depending on who's doing the inhabiting and what they bring to it. I suspect—but don't know for certain—that my life would have harder and less interesting had I grown up in Mills. It's the not knowing, of course, that makes it such a delicious ponderable. So I go back, and I look around, and I try to imagine who that boy might have been, what kind of man he might have become, where he might have gone and what he might have seen. And because Mom imagined something else entirely, way back in 1973, I can be ever grateful for the real story that lies alongside the conjecture. 6/11/2021 0 Comments How to Spend a Day in Montana** — one of an endless number of permutations 9:50 a.m.: Head out of Billings due west with fair Elisa. Destination: Livingston, 117 miles down Interstate 90. There is much I could say about Livingston, although it would be nothing that hasn't been said before by better observers with keener insights. I made a friend laugh earlier today by calling it my Emergency Backup Montana Hometown. That's how I feel about it and the people I encounter there. (It was good to see you, Marc Beaudin. It's always good to see you.) 11:45 a.m.: Meet Kris King for lunch at Neptune's. In my early days of designing Montana Quarterly, Kris—one of the magazine's steady contributors (she does the author interview each issue)—gave me shelter on my overnights to Livingston for final magazine production. She's a whip-smart, offbeat, fun, funny, wonderful friend who has been extraordinarily kind to us, and it was the first time we'd seen her in more than three years. (We moved to Maine. We moved back. There was/is a pandemic.) If you've read my short story Remember Me in Istanbul, you might remember the ex-girlfriend's house that a guy and his wife let themselves into on a winter night. I modeled that house, and the spirit within it, on Kris' place. Now you know ... Around 12:40 p.m.: Head a few blocks over and get a sneak preview of the forthcoming Edd Enders Retrospective. (June 18-19 in Livingston, and you should totally go if you're within driving distance.) It's one magical thing to be able to stare deeply into a single Enders work, which we're fortunately able to do every morning, as one adorns our bedroom wall. (I mentioned Kris King and her kindnesses; the painting below is one, a wedding gift that we treasure.) It's quite another to see canvas upon canvas, crossing all eras of his wonderful work. What a thrill for us. Around 1:15 p.m.: Head out for Bozeman, another 26 miles west. We ended up at the Emerson Center, a place I'd often heard about but never visited. There, I dropped off a copy of And It Will Be a Beautiful Life to Rachel Hergett, one of Montana's premier writers about the arts. It was our first face-to-face meeting, another unfortunate byproduct of the pandemic. Can't wait to renew acquaintances again and again. I'm telling you, there was a buoyancy to the entire day in this regard. We're opening up, and hope is flooding in where darkness once settled. I'm allowing myself to dream of literary readings and concerts and sporting events and dinners with friends. Around 2:45 p.m.: Two more stops, both essential. First, Country Bookshelf, one of the finest bookstores you'll find anywhere. What a wonderful feeling to see the new book paired up in the window with Sweeney on the Rocks by Allen Morris Jones. Allen and I are doing a virtual event hosted by Country Bookshelf on June 30. We'd love to see you. And then to also see it on the shelves ... I also scored a Gwen Florio novel. Signed. Who's the lucky kid? Finally, no trip to Bozeman is complete without a stop at The Baxter and the little chocolate shop in the lobby, La Châtelaine. Elisa had the Hawaiian red salt caramel truffle. I had the French martini truffle (below). We split a Meyer lemon truffle. No regrets! After that? Eh, there's not much to report. Just a 143-mile drive through some of the most beautiful countryside there is, pulled along by the mighty, north-flowing Yellowstone River, a ribbon to guide us home. In the best iteration of myself, I try to be grateful for the life I have and the way I'm able to live it, but circumstance and the intrusion of transient difficulties sometimes get in the way. Perfectly natural, of course, but also something that can swallow your perspective if you let it.

Today was all gratitude all the time. For this life, for this place, for these friends, for these adventures, for the next bend in the highway ... Originally published November 20, 2020

I knew the anxiety was coming before it made a full reveal of itself, when it was lurking several levels below the surface, before my toes began tapping, before my fingers started clenching and unclenching, before my attention started doing walkabouts in the middle of essential tasks. I knew what it was about. I knew what it wanted from me. I’m a restless man, which I grew into after being a restless boy and before that a restless baby. There’s a story that predates any of my memories, one told by my mother. She apparently went to my doctor and said, essentially, what gives with this kid? He stays up late. He doesn’t sleep through the night. Is this normal? And the doctor chuckled and said, well, there is no normal. If it affects his development, it’ll be something to address. If not, not. Well, here I am, fifty years on. We can have a debate sometime about how the whole development thing went, but this much is undeniable: I’m restless. In my work, in my relationships, in my interests, in my physical position on this earth. The coming anxiety was about that last bit. I needed to go somewhere. Our pandemic year makes the particulars of going decidedly more complicated than they were in the Before Times. Who’s going with you? Where? Who are you going to see there? You’re not going to eat indoors, are you? My answers, right down the line: My dog. Livingston, Montana, and points beyond and between. A couple of people. Fuck no. I told my wife on a Monday that I wanted to do it. No, that I needed to do it. On the subsequent Thursday, I did it. We did it, Fretless and me. It was about time. We’ve been back in Montana for a little more than seven months, Elisa and me and Fretless and Spatz the cat. We left Maine and our abbreviated experiment of living there as COVID-19 flared on the East Coast and the byways between Maine and Montana largely emptied out. We got a household and the contents of our lives moved not just once but twice—first into a temporary condo while we waited for the renters to leave the house we still owned here in Billings, second into the house. Through it all, we kept our heads low and ourselves relatively safe, even as the infections rose with ferocity in our old town that had turned new again. We formulated and ditched plans. No, we wouldn’t meet my folks in Denver. Too dangerous. No, I wouldn’t drive to Texas alone to see them. Too much of a time investment, and too dangerous. No, Elisa wouldn’t fly back East to see her mom and siblings. Too expensive, too much quarantining on both ends, too dangerous. It’s been mostly OK. I’ve been blessed with plenty to do, having a full-time job that was already conducted from home before the rest of the country discovered it out of necessity. Freelance jobs come my way—as many as I need and not more than I want. I’ve had a couple of pipeline inspection gigs—did I mention that I’m restless in the ways of work?—that I could drive to. We’ve been more fortunate than many. Our sacrifices—not seeing friends, not traveling at will, keeping our distance, wearing a mask—have been reasonable and not at all onerous. It would be errant of me to suggest otherwise. And yet … When you’re kinetic, a word that sounds so much better than restless, you sometimes have to go. I settled on Livingston for three reasons: 1. I can get there from here. 2. Of all the wonderful towns in Montana, Livingston is the closest thing to a second hometown to me. It’s the place from which one of my side gigs, as design director of Montana Quarterly, emanates. (I have mentioned the whole restless-in-work thing, right? Just checking.) There are friendly faces in downtown shops and on side streets and at restaurants, or at least there were when you could go to such places. 3. Parks Reece wanted an old wasps’ nest I cut down from one of my trees this fall, and he was willing to give me some of his art in exchange. Parks, in so many ways, is the perfect embodiment of the quality that has made Montana my home even though I didn’t grow up here, and a perfect illustration of what I hoped to find in Maine and did not, which compelled my return. I didn’t meet him on my own. He became part of my circle of friends because others, most notably my boss at the Quarterly, Scott McMillion, drew me into theirs. Think of the old trick with the chalices stacked in a pyramid, with wine filling the uppermost cup and cascading down until all of them are brimming. In nearly a decade and a half of living in Montana, this is what it’s been for me—I’ve made friends who’ve had friends who’ve become my friends. They fill my cup. I hope I fill theirs. I try. At Parks’ gallery, while Fretless alternately hid between my feet and ventured halting approaches to as many new people as he’s met in his short lifetime, we talked about this, what I’d looked for in Maine and hadn’t uncovered. Though I found the people there nice enough, there came a juncture where niceties ended and more intimate friendships were harder to penetrate. There’s very much a “from away” label that gets put on people who haven’t been in Maine for generations upon generations. It happens in Montana, too, but there’s often some dynamic tension to it. For one thing, if you’re a fifth-generation Montanan and you have some sense beyond yourself, you have to give some consideration to the idea that you and your people have been stealing what belongs to someone else for a long time. For another, there’s a welcoming nature I’ve found here that I didn’t find there. From the get-go with Montana, I’ve been comfortable with positioning myself as an outsider who found his way inside. I can’t claim it as heart earth. I can claim it as a found home. That didn’t happen in Maine, and it became increasingly clear that it wouldn’t happen in Maine. None of this is empirical, by the way, and I don’t want to end up in the weeds of who or where is more welcoming and why. This is merely my own experience, informed by who I was and when it was that I encountered each place. And that, I’m well aware, counts only so far as I allow myself to follow it. And, really, it’s not remotely my point here. Let’s move on. McMillion and I grabbed a couple of sandwiches and took them to Sacajawea Park, along the Yellowstone River, and had a socially distanced meal at a picnic table. Fretless got his first-ever scraps of people food, little chunks of bread tossed to him by Scott, and while I’ve been steadfast about not letting him become habituated to such delights, I had to relent. If I deserved a treat, so did he. The rapport Scott and I have is a solid and satisfying adult friendship, one I treasure and one that is built out of a few tentpole commonalities and a nice smattering of differences. He’s a hardcore outdoorsman, a hunter and a fisherman and a guy who knows his way around a canoe. I…am not. Scott likes to disappear into the backcountry or onto the vast prairie or down some stream. I think I’d like to rent an RV and park it in the shadow of a mountain, especially if the RV has a satellite dish and I can tune in a ballgame. We’re both big guys, mostly nonviolent, and as such we’ve had separate but similar instances of being drawn into physical confrontations that we’d have rather avoided in favor of a good book. He’s learned in the ways and the history and the art and the literature of his home state. I’m learned in the ways that get his magazine into print. We’re a good team, and we have some good laughs. After lunch, we walked along the Yellowstone River, giving Fretless a chance to stretch his stubby little legs, and we swapped stories of long-ago youthful indiscretions and more pressing contemporary concerns. Before Fretless and I left, I told him I was going to take the long way home, around the Crazy Mountains and up through White Sulphur Springs and Harlowton and on home to Billings. He said that sounded dandy. He probably didn’t remember the last time I’d taken that route. I sure as hell did. When I plotted the trip with Fretless, I didn’t think of just how microcosmic it would be of the total Montana topographical experience, but it really was: In a day’s driving, interrupted by several stops, I saw mountains and river valleys and glaciated plains and bald, flattop buttes and fallow fields. I drove through sunshine and rain and flurrying snow. I drove on dry asphalt and on icy patches where the sun doesn’t alight. I had a whole year in a single day in Montana. I find the mountains and the rivers easy enough to appreciate and admire. You have to work harder to love the prairie or the badlands or a flat stretch where the wind blows so hard that it threatens to knock you down. I’ve learned to express my unabashed ardor for that Montana, the one that generally doesn’t end up on postcards. I live in the eastern half of the state, where the land and the life are harsher and drier and more emptied out. I’ve spent a good chunk of my life now on that side of the state. There’s a depth of field to an endless horizon, and a clarity of thought you can find in pondering it. I missed that while in Maine, too, and hungered to come back to it. It’s become a part of me in unexpected ways. On Highway 89, in White Sulphur Springs, I took note of the little park I’d pulled into on an October day in 2014, when Elisa had been on the other end of my phone, trying to talk me out of a dark hole I’d crawled into. She wasn’t my wife then, just a friend who knew I was hurting, punctured by the twin disasters of an unfurling divorce and an ill-advised rebound romance that was doing what such things do. It was bouncing all over the damned place, battering me with each reverberation. My friend, on the East Coast, told me to hang in, that it would get better, that she didn’t much like to fly but she would get on a plane and see me through it if I needed her to. I told her no. She could sense the turmoil. She couldn’t see the whirlpool. I didn’t want her getting near it. I don’t want to overstate this or minimize what it is to be in true psychological danger. That day, that moment, I think I was in peril. I’d had a cup of coffee with McMillion in Livingston, and he’d talked me through some of the turmoil. He suggested I go back by circumnavigating the Crazies. Spend some time, he said. Let rationality have a go at me. Irrationality got there first. As I drove deeper into Montana, I thought more and more about pulling the car over, parking it, and setting out on foot. That’s when Elisa called. She told me to go to the next town and park and call her back. So that’s what I did. The particulars? I’ll hold tight to those. I’m here. She’s here. The stuff that hurt then doesn’t hurt now. Time and tide, man. White Sulphur looked the same but different today. For one thing, a different man drove into it, in a different year, in a different car, with a sweet puppy in the passenger seat rather than a festering bag of worry and regret. Upon driving into town, I had my mind not on my own pain but on the life of the great writer Ivan Doig, who grew up in White Sulphur and who drew on its impressions for a lifetime’s worth of work. I wondered what it was here that burned into his memory and stoked his imagination. I know a little something about the overdeveloped interior life of a writer; I, too, am afflicted. I never met the man, though I badly wanted to. I would have enjoyed talking about that with him. I read him voraciously starting at age nineteen, and his books were like guideposts into what I wanted to do and to be, even though I ended up treading different literary ground. The longer I do this—and by this, I mean go through this life, although I could just as easily mean attempting to distill the complexities of human life into a story that has a beginning and an end—the more I have to acknowledge that memory is at the thrumming center of damn near everything. It holds out caution. It transmogrifies into inspiration. It informs choice. It drives perspective. As I turned east on Highway 12 and headed into the homeward portion of the drive, memories came at me like bolt-action rifle shots. Here in late 2020, I ran headlong into midyear 2006, when I’d resigned from my job in California and planned a move to Montana with a sort of half-baked plan for a writing life. First, though, I had a trip that had long been on the books, hooking up with my father down in Albuquerque and driving, just the two of us, up to Great Falls, Montana, the part of the state he was from. It seems almost absurd now, as he’s still taking in oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide, but there was an elegiac tinge to that trip when we undertook it. His health had been not so good, and we wondered, or at least I wondered, how many chances we would get. With Fretless, I was driving east on Highway 12. In June 2006, Dad and I were driving west. In November 2020, I kept looking around for touchstones of memory, and I found them in the straightaways and in the rock formations that looked like stacked waffle cookies and in the river that alternately hugs the bends in the highway and rambles off into the distance. I fixated on one particular memory of that long-ago year, of seeing a rusting backhoe on the south side of the highway, stilled and silent and abandoned. In subsequent years, after my initial move to Montana, I would have occasion to go up to Great Falls, and I would spot that backhoe every time and recall the first time I saw it, and I would wonder why it had ever been put there and, more pressing, why it had been left to time and the elements. And brother, if you want to know where a spark of fiction comes from, consider the extrapolations you can make from that starting point. A forgotten backhoe beyond some fenceline. When? Who? What? Why? I looked for that piece of machinery today, in the dying light and amid the snoring chorus of my worn-out pup. It didn’t show. I might have missed it. The relentless vegetation might have overtaken it. Whoever left it there might have come for it at last. Who knows? At the junction with Highway 3, I bore right, Acton just ahead, Billings forty-some miles in the distance. Fretless stirred, activated and attenuated and bouncy, a dog who really should switch to decaf. I snapped one last picture, of the big sky that was over me and over the one who was waiting at home for me. I got on with getting there. The restlessness often gets what it comes for. Sometimes, I do, too. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed