|

2/7/2024 2 Comments Mind the LadderThere is a point to this, I promise, but I can't get there without first telling a sweet little story. So just bear with me, please... I've been contacting old friends on Facebook and other social sites, collecting mailing addresses. I'm having a literary reading and book signing this May in Texas, my first one in my home state in many years, and seldom does one get a chance to gather his foundational friends and acquaintances in one place and say thank you, for everything. I'm going to take that shot. The address search eventually led me to a man named Jim Fuquay, and that's where both the sweet little story and the point come in. Jim, an avid gardener, told me he was fighting the doldrums of February by reconnecting with old friends, that it had been a nifty little coincidence that I had reached out when I did. He asked me to give him a call, and I did, and let me tell you, it's been a long time since I enjoyed a half-hour as much as I did that one. But that's not the point. Jim was the first person to give me steady work in my first chosen field. It's been many years since that happened—thirty-five of them as of November of last year—and we both are, to state the obvious, much older now. We established on the call that he's eighteen years my elder (I honestly never knew the age gap, only that when we met, he was a fully mature man and I was...not). Eighteen years doesn't seem like that many now that I'm breathing heavily on age 54, but when I was eighteen years old and standing in his office, asking to be turned loose on writing newspaper articles, he sure seemed like an elder. An exceptionally kind and accessible elder, yes, but an elder just the same. Here's how I described Jim's decision to hire me in a public lecture I gave several years ago: The month before, I’d answered an ad in the Star-Telegram seeking correspondents for weekly community sections of the newspaper. I was eighteen, and the hiring editor wasn’t much interested in me until he read my clips. ... He gave me a job: the lowest-level, worst-paying, crappiest-assignment kind of writing job there was, but a job. Our deal was that I’d keep plugging away at school, he’d feed me a story opportunity every week or so, pay me $50 per, and let me build up a body of work. By late December...I had a story on the front page of the main newspaper. I was 18 years old, and I’d climbed a mountaintop of sorts. I wasn’t in the place I’d wanted to be, and I hadn’t made much headway into my half of the bargain with my boss, but I was getting somewhere. So many somewheres, as it turned out. During our phone call, I couldn't help reflecting on something that has crossed my mind plenty of times in my long working life, when I've considered how I got from there to here (and all the destinations in between): Jim didn't have to hire me. He could have given me a cursory look and sent me on my way, and his life would have been continued apace. Mine changed that day. A life has some number of true turning points, and that was one of mine. What Jim did that was so kind, so basic, and yet so uncommon is that he took a good look at me and imagined what I could be rather than fixating on what I was not. I was eighteen; I had no track record. I had only potential and gumption. Jim said yes to a kid who badly needed to hear that word. This is my point. And this is my plea: If ever you're in a position to take a gamble on someone, to surprise someone with a "yes" when you could save yourself time and aggravation with a brush-off, breathe that "yes" into the air. It could be the break that unlocks everything else for the recipient of that welcome word. I talk about this a lot with a friend with whom I lunch regularly. Where is the ladder anymore? What's a kid who doesn't emerge from the traditional mold supposed to do? What is a career and how does anybody get one?

When I was eighteen years old, in 1988, I was audacious in seeking a job, but at least I knew where to look. I had my eyes on a journalism career, and the procession into one was fairly well established at that point. You went to college. You gathered some experience. You did an internship. You caught on somewhere and started swimming. If you didn't read my public lecture, linked above, perhaps take a look now. I inverted that formula. More than that, I yanked it up by its feet and bounced it off its head. I bombed the college part, eventually. Internship? Never had one, at least not in a traditional sense. Experience? Not so much, no, not at that point. I came to Jim that fall bearing clips of stories I'd written for my high school paper. Not exactly a bastion of journalistic excellence. I came to him with chutzpah because chutzpah was all I had. Still, he said yes. He knew where the ladder was, knew he'd climbed it himself, knew the responsibility he had to make sure it was in good stead for someone else. He'd gained some latitude in his profession and spent some of it on me. A simple word, "yes," with fraught possibilities and potentially difficult outcomes. But what's the good of having a "yes" in your pocket if you're not willing to draw it out and slap it on the table? As we rang off, I thanked him for taking a chance back then. "I've never regretted it," he said. Neither have I, Jim. Neither have I.

2 Comments

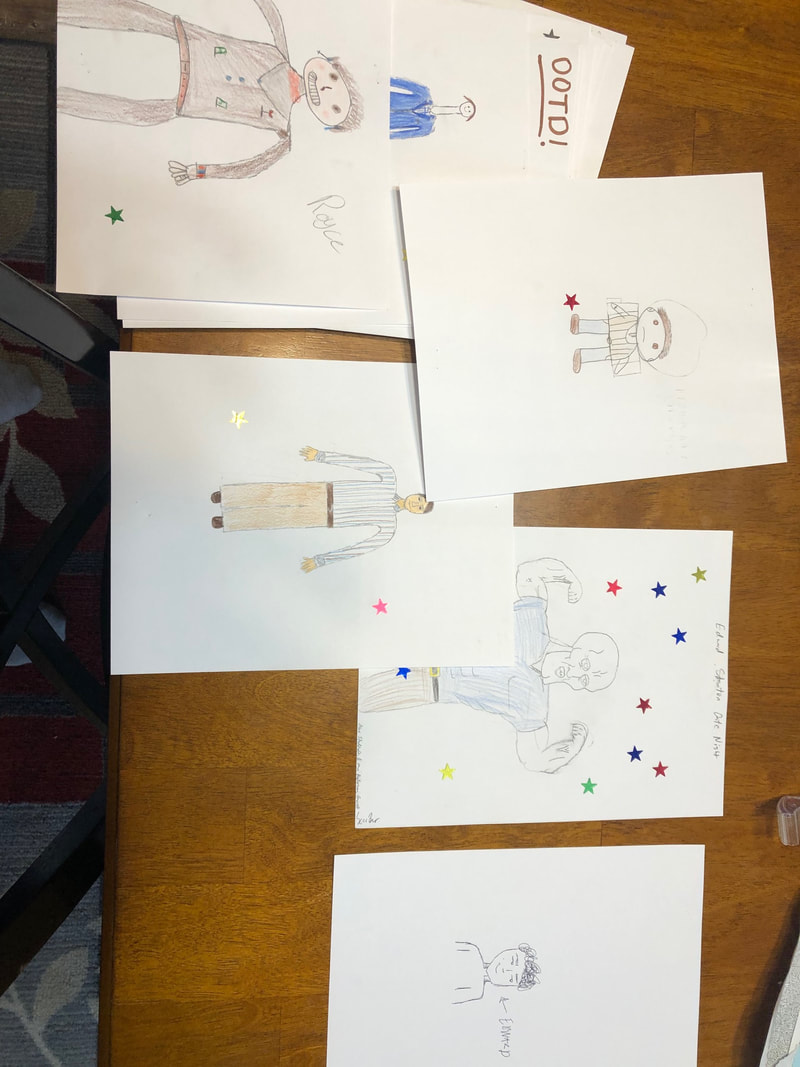

11/8/2022 0 Comments Books for Our* KidsIt's Tuesday, November 8, the first snow day of the season in Billings. Ordinarily, I'd have stayed in, but today I went out, and I'm glad I did. I delivered 40 fresh new copies of my debut novel, 600 Hours of Edward, to Skyview High School in Billings. That was the last of four deliveries I've made to Billings schools, for a total of 150 books. And the beauty of this is that I am merely the messenger, the delivery driver. These books—to replenish previous (and tattered) copies of the novel that have been in the schools for around a decade—landed where they did because of a community that answered the call. I asked for donations, enough to purchase those 150 books at a steep discount from the publisher, and my community funded the campaign inside of 12 hours. And when I say community, I mean Billings—so many people in Billings—but I also mean the larger community I'm privileged to call my own. Teachers in Virginia kicked in donations. A coworker in Ohio ponied up. Friends in Texas. People I didn't know until some cash landed. They did this because I asked for help in putting books in kids' hands. In this strange time in America, when we hear so much about taking books away from kids, these generous donors put books in front of them. It's a beautiful, radical act. As I so often do when the subject turns to the ties that bind us, I give thanks to teachers for doing what they do even as a significant slice of the population wants to fight them, deny them what they do well, castigate and smear them. This is shameful, yes, but it's also not new, and we can either let these angry, outsized voices have the floor, or we can meet them with a different set of values. English teachers where I live were instrumental in getting 600 Hours on the approved curriculum reading list for the high school level here in Billings. They saw a contemporary story of a neurodivergent character, one set in the town where their kids live, and they did the heavy lifting to ensure that they could teach that book in their classrooms. As I said in the Billings Gazette article about the first book delivery—thank you, Gazette—those teachers' dedication puts a responsibility on me that I'm only too happy to carry. “They’re the ones who pushed for this book because they know how to reach these kids. And if they’re the ones who are making sure of that, I’ll be the one making sure they have the books.” Damn right. A word about the asterisk up above.

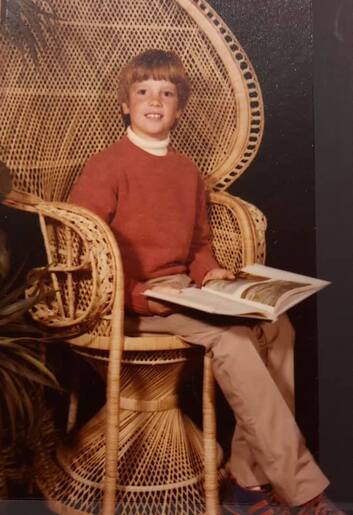

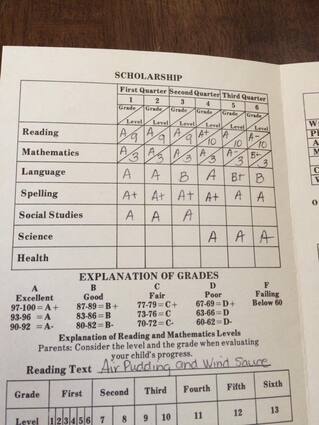

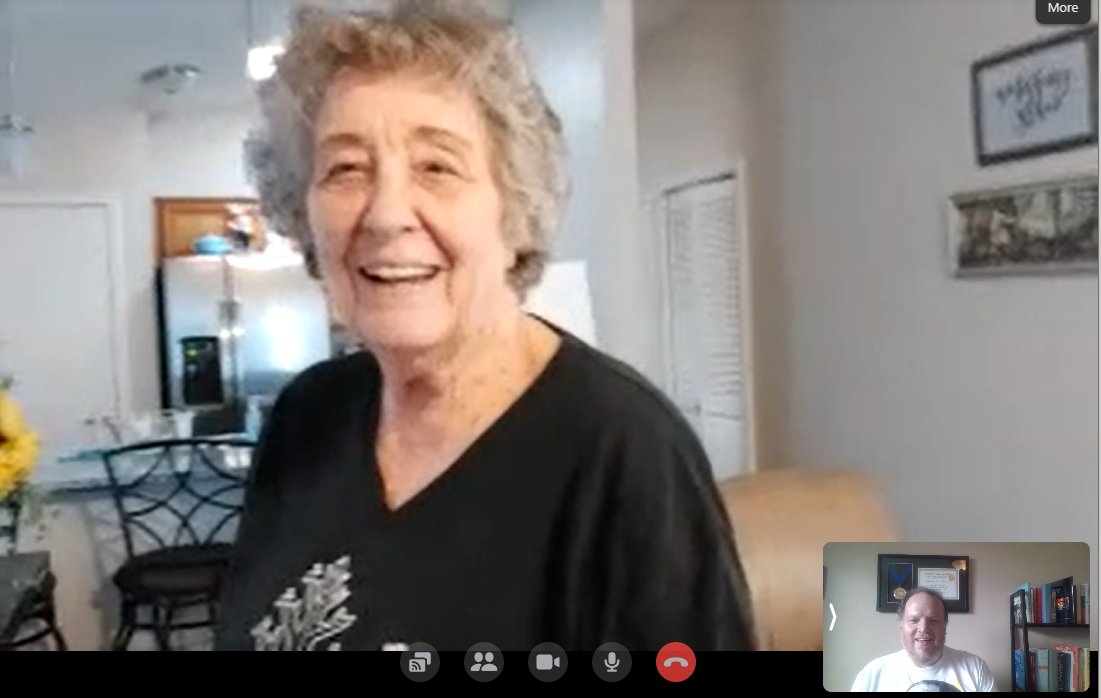

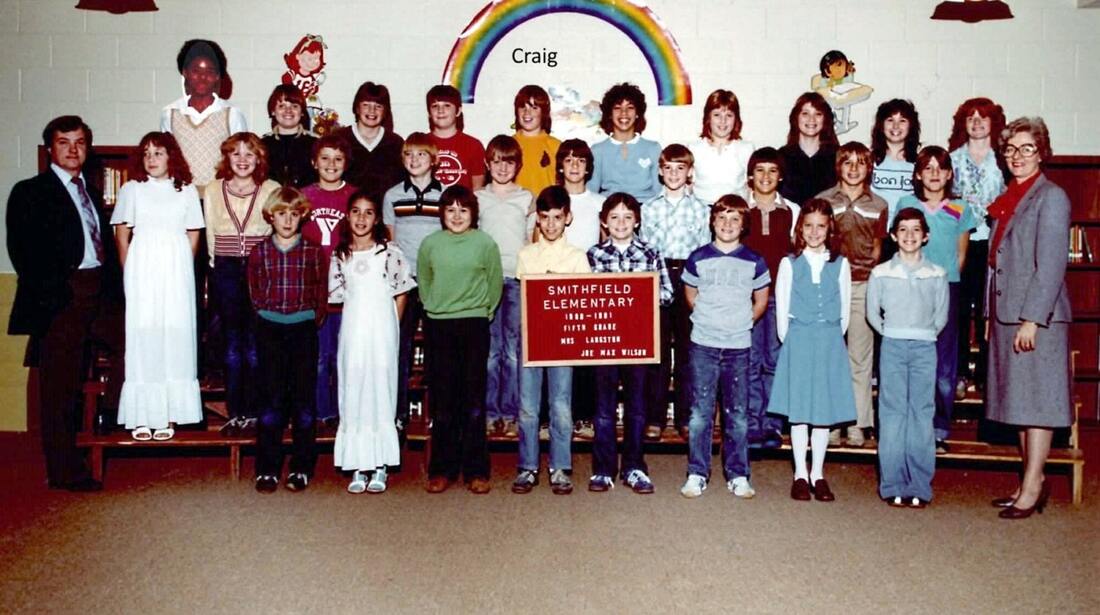

Yeah, they're our kids. I sometimes get a lot of pushback on this—"they're not my kids"—and I really wish someone taking the opposite view would spend just a little bit of time thinking expansively about the idea and the implications of abandoning it. My trip through public education was, in many ways, a disaster. It was also one of the most important factors shaping who I became and how I see the world. Certainly, public education is not perfect, and certainly, reasonable people can disagree on how to shape it, fix it, whatever. But we cannot, must not lose our responsibilities to ourselves and each other and the generations coming up behind us. Public education is a compact, an agreement that we will provide our kids with a basic education, as a community, knowing full well that our investments in those kids now are really an investment in our own future as a society. If we lose that, I'm afraid we lose everything else. So, today, I finished delivering some books. Backed by my community. Hopeful that the fight can be won. Determined to keep fighting, either way. 5/25/2022 0 Comments Some Who Shaped Me That's not a chair for reading, son. That's not a chair for reading, son. Today's little trip through the memory banks requires us to visit late summer 1978, a suburb of Fort Worth, Texas, called North Richland Hills, a neighborhood (and its elementary school) called Smithfield. Smithfield, in fact, was what most folks who lived there called the place back then. North Richland Hills, now a sprawling burg of about 70,000 people, was a relatively new concern in those days, having been voted into its own municipality 25 years earlier when Richland Hills, the now much smaller adjacent community, declined to annex the area. By 1960, North Richland Hills had gobbled Smithfield, a freestanding community to its north. The census in 1970 put North Richland Hills' population at just a shade more than 16,000 people. We were 30,000 strong by 1980, so you can sort of suss out the math for '78. We were getting bigger britches, for sure, but we were a cozy group. If you were to cleave off the people who thought of Smithfield as Smithfield, because that's what it had always been to them, you'd be left with an even smaller subset. Anyway, it was a different time and, in its way, a different place from what it is now. I was a different boy. There at the left, that's a pretty good approximation of what I'd have looked like (minus the wicker chair) as I pedaled off on a summer day to our neighborhood school, Smithfield Elementary, to see if the classroom assignments for the coming school year had been posted. When I saw that I had been assigned to Charlotte Cooke's classroom, I know I was overjoyed, for that's the teacher I'd been hoping to get as I moved on from second grade to third. So here's the thing: I didn't spend long in Mrs. Cooke's class. Maybe a week. Maybe less. I don't remember, exactly. What I do remember is that a new third-grade teacher started at Smithfield that year, a newly minted graduate who had been a late hire and was getting her first classroom at our school. As I recall, a class was built for her first by asking for volunteers to shift over from their assigned teacher to this new one. After that, the administration would do it by conscription. Again, here's where the finer details are lost to me in the intervening 44—holy shit, 44!—years, but I do remember that I volunteered. I do remember being concerned that if kids didn't act like they wanted to be part of this new teacher's class, she would get discouraged and think she was unwanted. I am certain—utterly certain—that given my affection for Mrs. Cooke, volunteering wasn't what I wanted. I felt like I needed to do it. Where such a notion came from, I have no idea.  I've made a lot of stupid decisions in my life. Made a lot of fortuitous ones, too, and volunteering for Donna Spurgeon's third-grade class in 1978-79 is a standout in the latter group. I loved her almost from the get-go—I do recall some initial cold feet about leaving Mrs. Cooke's class that my mother told me I'd have to overcome, having made a commitment—and I've loved her straight through. She later had my sister (twice, I think, after she moved up to a fifth-grade classroom), she changed schools and I kept up with her, I visited her classes a few times through the years, I was able to wish her a "well done!" when her retirement came through, and we keep the conversation going on Facebook even today. Back then, in 1978-79, I ended up feeling like I got the best outcome possible. Mrs. Cooke still figured into things, teaching me the perilous math of third grade (fractions!) and breaking me of the annoying habit of making my fours look like nines. But Donna was an all-timer, the kind of teacher I made it a point to keep up with as the seasons changed, for both of us. She started as a teacher (and even raked me pretty hard on my language skills, as evidenced by the report card above), then ended up as a friend. Doesn't get any better than that. So what of Mrs. Cooke. Well ... Sadly, I didn't keep up with her. I liked her, appreciated her, enjoyed her instruction, but time went on and so did I. And so did she. But let's go back to this idea of Smithfield as a place in time and as a heart's memory, just for a second ... There's a dedicated group of people who are from where I'm from, who've stayed, who haven't let the idea of Smithfield get too far away even as its time as a stand-alone town recedes. Every year, first weekend in May, there's a reunion. Living several hundred miles away, as I do and as I have for most of the past 35 years, I've never been to it. That's my failing. This year, I sent a stack of books to be included in a raffle, to hopefully play some small part in keeping these annual get-togethers going. A few days after the event, I got a text message from one of the organizers. She said someone had dropped by, seen the books with my name on them, and remembered me. Charlotte, she wrote. She was Charlotte Cooke, and she's Charlotte Williams now. Well, I'll be damned. A torrent of memory came on. You can see it, in every paragraph above. The organizer, LaDonna Powell, and I launched a conspiracy. We'd send her a book. I'd enclose a card. We'd spring a video chat on her. We'd close this circle that's been hanging open since Jimmy Carter was president. There she is, and there I am, all smiles for our long trip back to each other. I'd like to say I would have known her on sight, on the street, but I probably wouldn't have, and I'm certain she wouldn't have known me. But as we talked—just briefly—I could see the flickers of kindness and care that made her such a wonderful teacher for all those years, one whose classroom I badly wanted to be in when I was 8 years old and rode my bicycle down to the school to see if the luck of the draw had been with me. It had been, and yet I asked to be reassigned, which turned out to be only one of the most consequential decisions of my growing-up years.

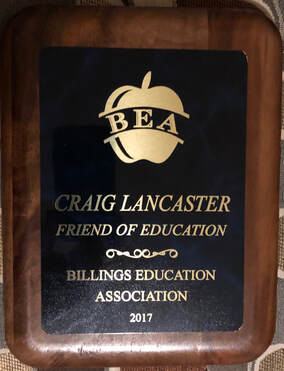

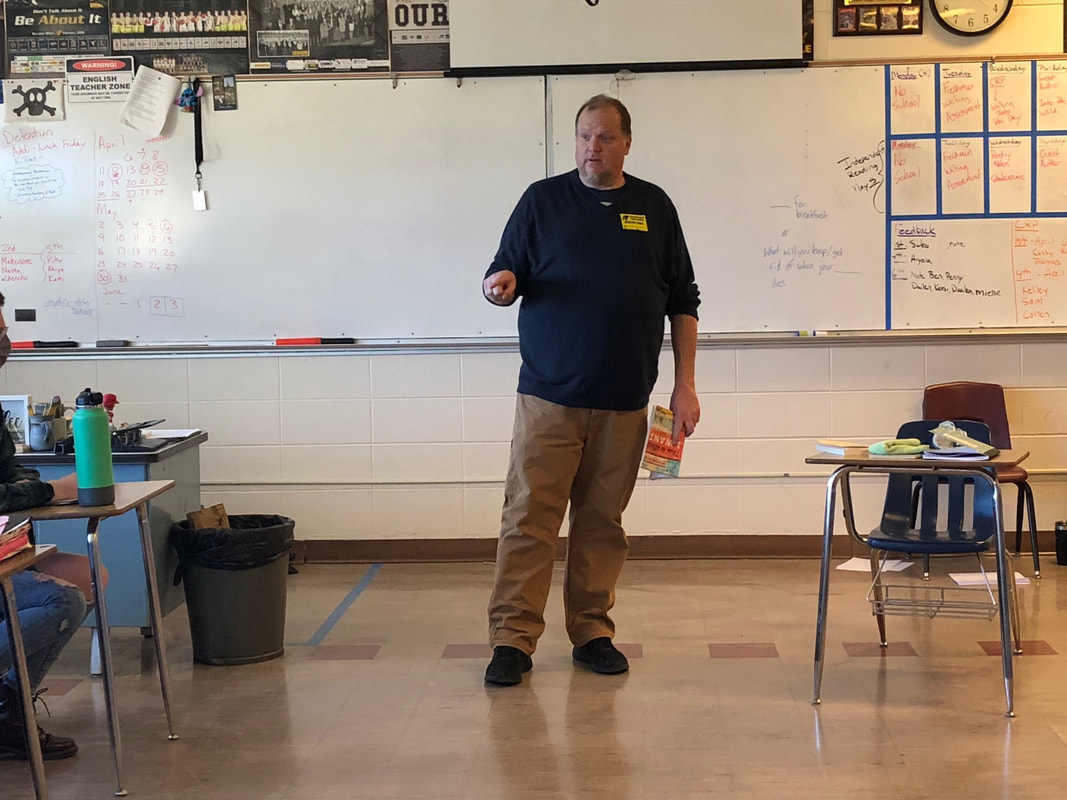

Sometimes, it all works out. What I said to Mrs. Williams, in our chat and in the card I included with her book, is between the two of us. In the broad strokes of it, I can say only that I'm grateful. For the kindness of the teachers I've known, whether chosen by me or for me. For the intercession of LaDonna. For the chance to say thank you, and to mean it. Thank you.  My favorite bauble. My favorite bauble. I've been fortunate enough to have had some terrific honors bestowed upon me. Fifth-grade spelling bee champion. Sixth-grade student council president. I mean, do I have to go on? We're talking biggies here. It was just about this time of year in 2017 that, perhaps, the one that means the most to me came around. The Billings Education Association—the union for public school teachers in the place I call home—honored me as its Friend of Education. It was deeply meaningful to me for several reasons. One, I'm a child of public education (thank you, Birdville Independent School District and Smithfield Elementary, Smithfield Junior High (now middle school) and Richland High School). Two, public school teachers have had a profound effect on me at every stage of life. They've been mentors and influencers and friends. I was born to one. I married one. Three, I truly believe that public education is a compact we must hold with each other, no matter how fraught things get (I'm not terribly optimistic about how things are going in that department, but I still believe in the compact). Public education is the ultimate investment in our future, together. I could go on and on. I have, in fact. Whatever the teachers in my town felt in calling me their friend five years ago, I send it back in triplicate to them. English teachers at West High School here in Billings were instrumental in getting 600 Hours of Edward on the approved curriculum list at the high school level, and for years now, some of them have been teaching it. It blows my mind, still. And the bargain I've made, straight along, is that if you want me to visit the classroom, to talk about writing and creativity and life beyond high school, tell me when and where and I'll be there. The pandemic, as you might imagine, took a bite out of that bargain. And yet, there we were last week, a handful of English classes at West—juniors and seniors—and a creative writing club, and we were working through one of my favorite writing exercises, The Word (I am not its inventor, by the way, just an enthusiastic adopter). Each class, I'd have the kids tell me their name and give me a word. We then ran a random-number generator to choose a single word that the entire class had to use as inspiration for a short story. Writing time: 20 minutes. It's a hell of a thing, I'm sure, to show up one day at school and hear that some dude you've never met before wants you to spend most of a period writing. But these kids did it, and their enthusiasm, generosity, and talent leave me hopeful for their futures and my own. For every period, I wrote alongside them, ending up with nearly 3,000 words of material, by far a busier day than I usually have. I'll spare you the whole passel of short stories (unless you really want to read them), but here's a taste: Lightning When we got the dog—a 48-pound, 40-inch-long, 14-year-old basset hound—I named him Lightning because, among other things, I was into irony. Lightning’s name was Dexter when he was stuffed in a kennel at the humane society, on account of his previous owner, an 84-year-old woman named Mildred, up and died one day and Dexter was found sleeping in the small of the back of her tumbled-over carcass, and Mildred’s kinfolk didn’t want him. And you might say that if a dog has borne a name, any name, for 14 years, he ought to be allowed to keep it for the rest of whatever time he has left. And, OK, that’s a fair point, but Dexter is a crappy name and no more fitting the hound he was than Lightning was. So I changed it. My prerogative. We didn’t get off to a good start, Lightning and me. First night, I put him up on the bed, and he walked around behind my shoulder, I thought he was snuggling in, and he lifted a leg on me. New house, new bed, new people—I guess I can’t blame him, but come on, man. He pooped on the rug the next day—the good rug, that was the problem, not that frayed thing in the den—and I thought, well, Lightning, you ain’t long for us if you don’t straighten up and fly right soon. I needn’t have worried, as it turned out. I’ve come to believe, in the looking back, that the speed of him—opposite the name we’d hung on him—was the secret to his longevity. That dog just wasn’t in a hurry for anything, which kept his heart rate low and his blood moving agreeably. “Lightning, dinner,” we’d say, and we’d wait for the lumbering, this long dog who could have two feet on different sides of a corner, and he’d come into view and he’d eat at a luxurious pace, like a cow working its cud. “Lightning, let’s get in the car!” Same thing. That dog moved in a way that would make a sloth say, “Damn, that’s one slow-moving animal.” Ironic, then, that the event for which he gained his fame around our house, the reason Judy would grip him by those jowls, unbidden, and say, “You’re the best dog ever, yes you are,” was a moment of alacrity. Megan, our youngest, just a baby, crawling for the curb and the traffic beyond, we’re bound up in watching Mitchell show us his batting stance there in the front yard, and she’s nearly to the asphalt, and here’s Lightning, moving at his bah-doop-dee-doo pace and he snags her diaper in his teeth and pulls her back. That’s a good boy. We said goodbye to him last night, the fadeout that we’d seen coming and were still flabbergasted by when it arrived. Lightning, staring up at us, our expectant faces in his, our tears surfacing, and here’s that old floppy-tongued kiss, the one we’d had a thousand times and would never have again, and he’s gone, gone, gone, not so much a flashing discharge of electricity but a shattered star lighting up our days and nights.  With Hazel Lowrance, my kindergarten teacher (1975-76), in March 2022. With Hazel Lowrance, my kindergarten teacher (1975-76), in March 2022. After writing and sharing—the kids were great about that, too—we talked about what I like so much about this exercise, that in the letters and meaning of a single word, there's a fuse that can be lit and burned down into a burst of creativity. It's one of the most magical things I know of, how you can tap into memory, word association, imagination and pull a story right out of yourself. It's entirely egalitarian. You don't need permission. You don't have to wait for someone to judge you worthy. You just need time and inclination. You need a pencil and a piece of paper and the willingness to get busy. And the thing is, long before I ever thought about these things, long before I ever knew what a writing prompt was, long before I ever imagined trying to build a life around words, I had teachers who pushed me, who had lamplight and were willing to show the way, who truly and honestly believed that each child in their care had purpose and something to offer. On the surface, I don't have much in common with those kids I met last week—I'm older than their parents, in many cases, and from a generation that must seem decrepit and dated to them. And yet, the successors of those teachers I remember with such fondness and admiration are in the classroom now. Still pushing. Still guiding. Still believing. How lucky we are. What a shame it would be if we lost it. 6/10/2021 0 Comments Teaching and Beyond BurnoutOriginally published March 25, 2021

The most attention-getting thing I’ve read in the past week is this piece by Anne Helen Petersen, titled “What Demoralization Does to Teachers.” It took hold of me not just because I’m friends with a lot of teachers (I am) or because I see the factors outlined in the article playing out among those friends (I do). What stopped me cold was the distinction between burnout and what’s really happening to teachers: They’re demoralized. From the piece: What educators are feeling right now — what they’ve felt over the last year — is not just frustration and fear inspired by the pandemic. It’s not just burnout. It’s way beyond that. It’s chronic burnout and deep demoralization as their labor is increasingly under-funded, under-valued, and under-resourced. Wait, there’s more. In an article cited by Petersen, which you can read here, Doris A. Santoro writes: One reason people are not attracted to teaching, and why some are leaving teaching, is that they do not see it as a place where they can enact their values. I daresay demoralization is a destructive force whatever your line of work. What makes it so alarming in the teaching realm, of course, is that education is the bedrock for everything that follows. If we’re torching teachers—not just working them hard but also causing that work to have no meaning to them—who pays on the back end? The answer is obvious. If you think we have a problem with chronic ignorance now (and, yeah, I think we do), what happens when we’re chasing teachers out of the profession and, consequently, are unable to attract the sort of folks who have historically flocked to it? I don’t have to look far to see the worrying signs. I have a dear friend who is leaving teaching at the end of this school year. She’s not ready for retirement; indeed, she’ll have to continue working to pay the bills, retain health insurance, put gas in the car, etc. But she’s done teaching, after a long, distinguished career of doing it, after a long time of feeling called to it. But she can no longer take the misplaced priorities, the undercutting, the under-funding, the many obstacles that are lined up to stand between her and what she knows will get results in the classroom. She’s done, and it’s her community’s loss. Our community’s loss. And I suppose that would mean so much more if our community even understood what’s happening to her and, by extension, to all of us. Several years ago, I taught a semester-long honors fiction-writing course at Montana State University Billings. It was harder than I ever imagined it would be, and I have a pretty vivid imagination for such things. But I threw myself into it, and indemnified as I was against the more tedious aspects of being an instructor there—I was a visiting writer, so I didn’t have committee assignments or faculty meetings or anything else of that nature—I tried my best to make connections with the self-starting students who’d chosen the course, to impart what I’ve learned but mostly to help them find ways into expressing their art. At the end of the semester, I gave a public lecture, and I chose public education as my topic, focused through the lens of my uneven relationship with it. As part of that, I asked my teacher friends to tell me what they wished their communities knew about their jobs. Some of those responses: How deeply I loved each and every student that came into my classroom. Even the ostensibly unlovable ones, I worked until I could love them, until I could see their unique and spectacular gifts. I want people to know the system is designed to use that love against you, pencil after pencil, lost planning period after lost planning period. I burned out so fast, and I wish there had been a system interested in retaining me. And ... I think people need to know how functionally illiterate most college students are … and how unsurprising it is, given how teachers at lower levels lack any sort of empowerment or incentive or respect. And ... All I want to do is teach in the way that I know is developmentally appropriate for kids. That is all my colleagues want, too. This was pre-pandemic, far enough back to be a memory and close enough to touch us. We’re in trouble, folks. We have been for a long time. The pandemic accelerated matters, but the trajectory has been disastrous for a while. Empathy for the demoralized is not hard to come by. I spent twenty-five years as a newspaper journalist, the very definition of “been there, done that.” At the end, amid quarterly staff purges, scaled-back coverage, “doing more with less” and other assorted bullshit, I walked away and into an uncertain future working life. I left not because my pay was low (it was, relative to other jobs I had the skill to do) or because it was hard work (it was ever thus). I left because the work that had been so important to me for so long didn’t seem to matter anymore, because I’d been implicitly told by the powers that be that I didn’t matter. I was a cost center, one that was aggressively being pared back. (And now, the vultures that have control of much of that line of work argue that people who do what I did for all those years aren’t journalists at all. It’s as if the business model is degradation.) And you know what? Maybe I didn’t matter at the end. If that’s so, I cut them before they could cut me. That’s a decidedly different outlook than the one I had when I entered the profession. Twenty-five years of steady erosion and declining standards beat me up pretty good. I have great affection and nothing but good wishes for those who keep answering the call at local newspapers. They are doing what I could not. Setting my own experience aside, I think it’s fair to say that when the folks develop a feeling Santoro widely ascribes to teachers—“Demoralization occurs when teachers cannot reap the moral rewards that they previously were able to access in their work”—it’s not something that can be soothed with a little time away, some breathing exercises, and some cinched-up self-care. At some point, the demoralized give up and leave, and nobody who cares the way they once did can be compelled to step in, and then what? I’ll say it again: We’re in trouble. |

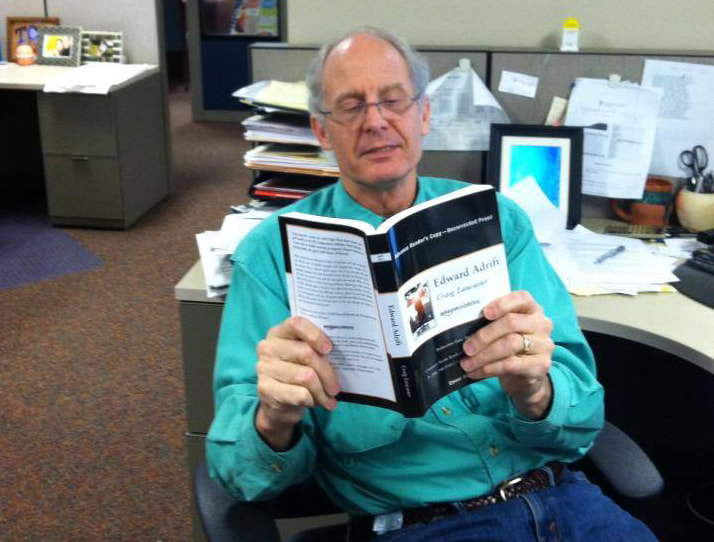

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed