|

6/10/2021 0 Comments Teaching and Beyond BurnoutOriginally published March 25, 2021

The most attention-getting thing I’ve read in the past week is this piece by Anne Helen Petersen, titled “What Demoralization Does to Teachers.” It took hold of me not just because I’m friends with a lot of teachers (I am) or because I see the factors outlined in the article playing out among those friends (I do). What stopped me cold was the distinction between burnout and what’s really happening to teachers: They’re demoralized. From the piece: What educators are feeling right now — what they’ve felt over the last year — is not just frustration and fear inspired by the pandemic. It’s not just burnout. It’s way beyond that. It’s chronic burnout and deep demoralization as their labor is increasingly under-funded, under-valued, and under-resourced. Wait, there’s more. In an article cited by Petersen, which you can read here, Doris A. Santoro writes: One reason people are not attracted to teaching, and why some are leaving teaching, is that they do not see it as a place where they can enact their values. I daresay demoralization is a destructive force whatever your line of work. What makes it so alarming in the teaching realm, of course, is that education is the bedrock for everything that follows. If we’re torching teachers—not just working them hard but also causing that work to have no meaning to them—who pays on the back end? The answer is obvious. If you think we have a problem with chronic ignorance now (and, yeah, I think we do), what happens when we’re chasing teachers out of the profession and, consequently, are unable to attract the sort of folks who have historically flocked to it? I don’t have to look far to see the worrying signs. I have a dear friend who is leaving teaching at the end of this school year. She’s not ready for retirement; indeed, she’ll have to continue working to pay the bills, retain health insurance, put gas in the car, etc. But she’s done teaching, after a long, distinguished career of doing it, after a long time of feeling called to it. But she can no longer take the misplaced priorities, the undercutting, the under-funding, the many obstacles that are lined up to stand between her and what she knows will get results in the classroom. She’s done, and it’s her community’s loss. Our community’s loss. And I suppose that would mean so much more if our community even understood what’s happening to her and, by extension, to all of us. Several years ago, I taught a semester-long honors fiction-writing course at Montana State University Billings. It was harder than I ever imagined it would be, and I have a pretty vivid imagination for such things. But I threw myself into it, and indemnified as I was against the more tedious aspects of being an instructor there—I was a visiting writer, so I didn’t have committee assignments or faculty meetings or anything else of that nature—I tried my best to make connections with the self-starting students who’d chosen the course, to impart what I’ve learned but mostly to help them find ways into expressing their art. At the end of the semester, I gave a public lecture, and I chose public education as my topic, focused through the lens of my uneven relationship with it. As part of that, I asked my teacher friends to tell me what they wished their communities knew about their jobs. Some of those responses: How deeply I loved each and every student that came into my classroom. Even the ostensibly unlovable ones, I worked until I could love them, until I could see their unique and spectacular gifts. I want people to know the system is designed to use that love against you, pencil after pencil, lost planning period after lost planning period. I burned out so fast, and I wish there had been a system interested in retaining me. And ... I think people need to know how functionally illiterate most college students are … and how unsurprising it is, given how teachers at lower levels lack any sort of empowerment or incentive or respect. And ... All I want to do is teach in the way that I know is developmentally appropriate for kids. That is all my colleagues want, too. This was pre-pandemic, far enough back to be a memory and close enough to touch us. We’re in trouble, folks. We have been for a long time. The pandemic accelerated matters, but the trajectory has been disastrous for a while. Empathy for the demoralized is not hard to come by. I spent twenty-five years as a newspaper journalist, the very definition of “been there, done that.” At the end, amid quarterly staff purges, scaled-back coverage, “doing more with less” and other assorted bullshit, I walked away and into an uncertain future working life. I left not because my pay was low (it was, relative to other jobs I had the skill to do) or because it was hard work (it was ever thus). I left because the work that had been so important to me for so long didn’t seem to matter anymore, because I’d been implicitly told by the powers that be that I didn’t matter. I was a cost center, one that was aggressively being pared back. (And now, the vultures that have control of much of that line of work argue that people who do what I did for all those years aren’t journalists at all. It’s as if the business model is degradation.) And you know what? Maybe I didn’t matter at the end. If that’s so, I cut them before they could cut me. That’s a decidedly different outlook than the one I had when I entered the profession. Twenty-five years of steady erosion and declining standards beat me up pretty good. I have great affection and nothing but good wishes for those who keep answering the call at local newspapers. They are doing what I could not. Setting my own experience aside, I think it’s fair to say that when the folks develop a feeling Santoro widely ascribes to teachers—“Demoralization occurs when teachers cannot reap the moral rewards that they previously were able to access in their work”—it’s not something that can be soothed with a little time away, some breathing exercises, and some cinched-up self-care. At some point, the demoralized give up and leave, and nobody who cares the way they once did can be compelled to step in, and then what? I’ll say it again: We’re in trouble.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

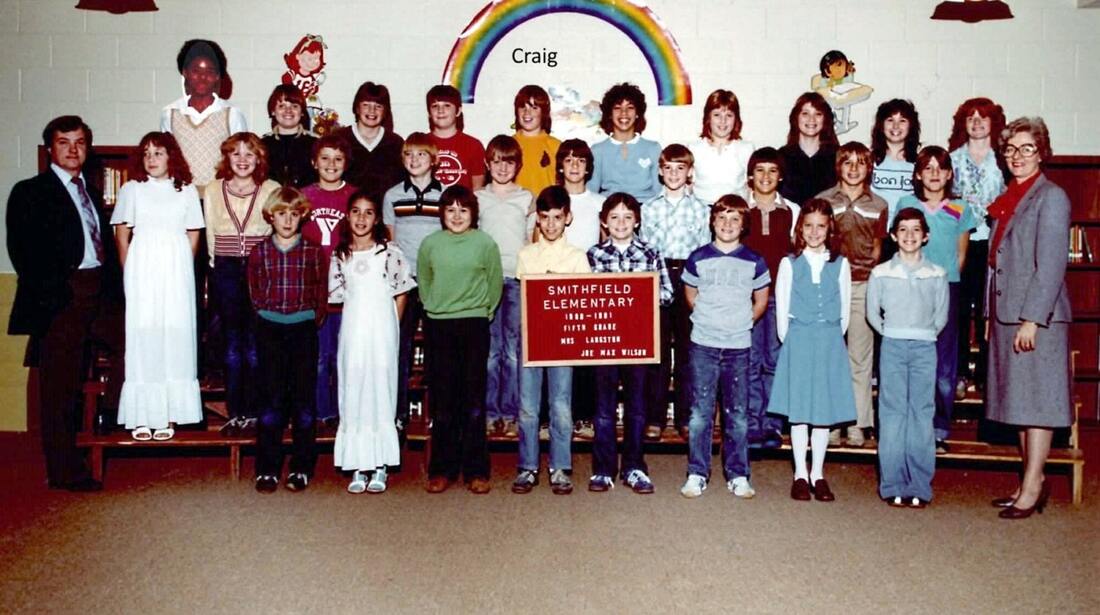

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed