|

7/13/2024 0 Comments The Vicissitudes of Life**--I used this phrase in my most recent newsletter, and one of my dearest friends wrote me a wonderful email with it as the subject line. Consider this a case of virtuous recycling. It has been nearly two months since I put something new up here. Sorry/not sorry, as the saying goes. So much has happened, and I have so little to say about it, and that's a strange combination. Confronted by this dynamic in the past, I've found it best to turtle up and wait until something worthwhile comes to mind. If you're seeking mindless blather, surely there's a high-frequency, low-content Substack site out there for you. And yet, enough has changed, and enough good intentions have been met with poor follow-through, that an accounting is in order. Let's do this scattershot style: I've moved. But that's not all. Elisa covered this beautifully in her own newsletter, so I'll neither say a lot more nor take issue with any of it. She now lives in New England, her other heart earth, and I still live in Montana, mine. I'm renting space in a lovely old rambling house in my favorite Billings neighborhood, pushing on with life and art. I have a beautiful office setup that is a joy to pile into each morning. My primary work, which I find interesting and fulfilling, continues apace (you can read a piece I wrote for PaymentsJournal here). Fretless and I take walks, sometimes alone, sometimes with my roommate and her dog. I tend to my dad. I have lunch with friends. It's a good life but also a different life, and I think Elisa would say the same thing. Fiction: At a standstill Once I decided to spring Northward Dreams loose from its intended publisher, spring became a blur as I pushed out a retitled, re-jacketed version of the book and embarked on an ambitious series of appearances. Those have largely subsided as summer has come on, and it will probably be fall before I rev up again. The paperback comes out in November, and that's a good opportunity to hit the road again. I had so much fun with the hardcover. What hasn't been fun—and I'm only being honest here—is going through the wringer of publishing, which can be a heartbreaking business. Writing is the best kind of joy—challenging, yes, but also a test of self, of the quality of ideas, of endurance. Publishing...Well, if I can't say something nice, and I can't, best not to say anything at all. It's not like my travails register as important in the larger scheme of things; hell, they're not even all that interesting to me given all the ways the world is on fire (literally). But if I'm going to write stories—and I am—I will have to resolve my attitude one way or another. Right now, I feel three impulses: 1. Forget publishing altogether. 2. Find another partner like the one I just dispatched, something I never wanted to do, and approach the altar again. 3. Do with every subsequent book exactly what I did with this one. Until my heart settles, I'll do nothing. Playwriting: Stay tuned After the final curtain closed on Straight On To Stardust last fall, I set about writing a new play and turned it around quickly. It's called The Garish Sun--know your Shakespeare—and I hope to have some interesting news to pass along soon. #deliberatetease At this juncture, I'm much more interested in and satisfied by working as a dramatist than I am in writing another novel. These feelings, of course, are subject to change (and always do), so I wouldn't read anything into that declaration. Just something I wouldn't have predicted, say, three years ago. Life, man. Let's have a conversation At the beginning of July, I joined at the speaker roster at Humanities Montana. I'm thrilled about this, as a longtime admirer of and sometimes participant with this organization that advances the humanities in Montana's public life. My program, titled Where Memory and Imagination Meet, draws on subjects that have long held fascination for me—the roles of memory as an ignition point and imagination as the building blocks of fiction—but expands the idea to take in such diverse topics as family, background, community, even citizenship. When we talk about our memories of the things that shaped us and marry those with imagining different ways of talking and connecting, great things can happen. My program, like all the others sponsored by Humanities Montana, is available to schools, libraries, civic groups, and other such gatherings. Information at the link above. If you have a group in Montana that would benefit from this conversation, let's talk! Yeah, but what about all the other stuff? Oh, you mean Craig Reads the Classics? The Saturday craft talks? General keeping in touch?

What can I say? I've been quiet lately. But I'll be back. That's a promise.

0 Comments

5/21/2024 0 Comments Texas. Redux.

I wrote about my home* state several weeks ago. It was a wide-angle, pulled-back view, and I thought I'd unloaded what was in my heart and my head. But here I go again...

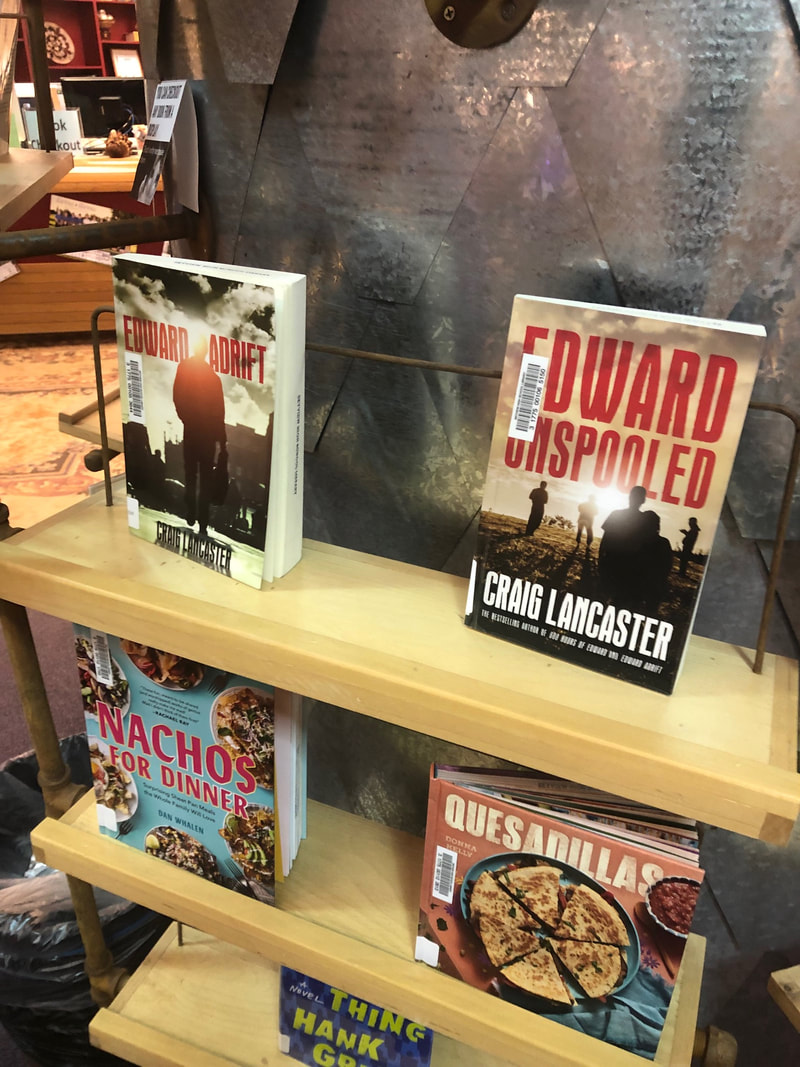

No, really, here I go. It's a quick trip this time, not my usual two-day drive down, weeklong stay, and two-day drive back. I'm going for a reading and signing at a bookstore in Keller, the once-sleepy town just north of where I grew up. Like other parts of the North Texas I once knew, it doesn't really match up with my memories anymore. It's bigger, more congested, more diverse, more interesting.

The book I'm taking with me, Northward Dreams, is the most personal piece of fiction I've ever written. The best thing I've ever written, too, not that anyone should trust me to judge such a thing. I'm proud of it. I'm proud of how I willed it into existence. And I really, really want to share it with the people who underpin it, in ways subtle and overt. They're in the book, all of them, whether they would recognize themselves or not. They're in it because they're in me, in the memories I carry around.

To that end, I sent out about 100 postcards earlier this year, addressed to people from across the years I spent in Texas: classmates, old neighbors, former bosses, teachers, colleagues, friends, former lovers. I asked them to come out and see me and to meet this book, to renew acquaintances or to prolong friendships that never ran dry. I'm hoping to see a constellation of faces I recognize come Saturday, but I've also put this event squarely in a holiday weekend, so who knows? I haven't always done a wonderful job of staying in touch as I've wandered the country, looking for the place I'd call home. I found it, years ago. But I've also come to realize that the place I'm from—as much as I'm from anywhere—is also home and always will be.

When I say Northward Dreams is my most personal book, I'm thinking, among other things, about this snippet from one of the four timelines the novel covers. Here, in 1972, Electra and her little boy have arrived at their new home in Texas:

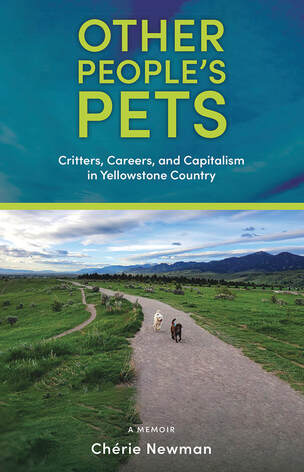

After they’ve gone downstairs, after Electra has made her assessment of the pantry, after she’s pictured the days stretched out before them, after Nathan, red-faced and watery-eyed, has come down and asked for a glass of water, after Charley has fetched the rest of their things and stacked them by the door for sorting out later, after they’ve come back up the stairs, quieter, the three of them lie askew on the king bed. Charley is on his side, head propped up by an angular arm. Electra lies far opposite of him, attentive to her son, and Nathan sleeps in between, curled like a kitten’s paw and under a loose blanket. Electra reaches across the distance, and Charley takes her hand. “Probably not what you expected.” “It’s everything I expected,” he whispers. “You?” “It’s what I want,” she says. “Me, too.” “He’s really a good boy,” she says. “I know.” “It’s a lot to deal with.” “It is.” Charley sits himself up, careful not to jostle the boy. “Kids are resilient, though. I ever tell you about when we moved from Vernon to Wichita Falls?” “No. I’d remember.” “You went through both towns,” he says. “I know.” “I wish I could have been there.” “I know,” she says. “Fifty-some miles, might as well have been moving from earth to the moon. I was nine. Everything I knew, every friend I had, they were all in Vernon, but my dad, he was a history teacher, and the high school in Wichita Falls, they offered him $15 more a week, so we moved. I didn’t have any say.” “Had to be hard at that age.” She’s thinking now of Nathan’s best friends, the Miles boy two doors down and the Fletcher kid, the one she doesn’t much like but whom Nathan adores, and how she plucked him up and took him away without his getting to say goodbye. She hurts for him in a way that she hasn’t allowed herself to think about until now. “Hard at any age,” Charley says. “But the thing is, in the end, I made new friends. Wichita Falls became home, every bit as much as Vernon had been. I adjusted. He’ll adjust, too.” “Tomorrow,” she says, more thoughts she’s held at bay rushing toward her now. Enrolling Nathan in school. Finding a job. Learning where the supermarket is. “It’ll all get done,” he says, as if inside her head. It’s a talent he has. She leans across and kisses him for the first time. Where all of that comes from is both imagination and memory, little snippets that I heard, others I conjured, all of it front and center in my brain, ready to be accessed when I got hold of a story that needed it. This story. This place. Another time of life, forever salient because the decisions that were made had such gravity to them that their effects radiated out to lives yet to be launched. It's powerful stuff, fiction. Often more powerful than the real life that informs it. 3/2/2024 0 Comments Q&A: Chérie NewmanToday, it's my pleasure to host one of my all-time favorite human beings, Chérie Newman, as she answers some questions about her book Other People's Pets: Critters, Careers, and Capitalism in Yellowstone Country.  One of the things I like best about Chérie is how deeply she thinks about things, a tendency of hers that is written across her answers to my questions (and I promise, we're getting there soon). Then, of course, I'd have to consider the other things I like about Chérie, and the list grows. She has wide-ranging talents, she's a supportive pillar of the culture she exists in, and as I know from personal experience, she'll drive a few hours to see your play. (Well, maybe not yours. But mine. Thanks again, Chérie!) I've known her for going on two decades, and I'm continually impressed by the breadth of what she dips into and becomes proficient at doing. Without further ado, then, here's Chérie Newman and her thoughts about Other People's Pets...  I'm fascinated with the resumption of your—not career, really, but work—as a pet sitter after a long break from it. What prompted that? Was it like riding a bike, as the saying goes, or were there rigors to the second go-round you didn't anticipate? The resumption of my work as a pet sitter happened during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Before March of 2020, I earned most of my freelance income as a podcast editor, working with audio files recorded during live events. Then, suddenly, there were no live events. No live events meant no money for me. My hasty reaction to the loss of income was to accept a job as an office manager. Yuck!! I do not like office work. So, I quit that after a year and agreed to become a subcontractor for a Bozeman pet sitter who had way more work than she could handle. This was the end of 2021, when many people were starting to travel again. She started sending me on interviews and that’s when the fun began. Although, I’ve taken care of other people’s pets all my life, it was mostly for friends and family. Right now, I can only think of four or five people—“clients”—who hired me as a professional, home-stay pet sitter between 1990 and 2022. The rigors, as you say, of these new situations were complicated and multi-faceted. Most of the people I worked for were nice. But they weren't paying a lot, and their expectations were high. And, I have to say, that even though they were paying me two or three times the amount I’d earned before, the average hourly rate came out to about $4 an hour. Four dollars an hour for being on duty 24/7 is not great. Especially when you factor in responsibilities for other people’s property, package delivery (Why do people order stuff when they know they’re leaving town?), invisible fences that fail and other high-stress events, and the fact that most of the houses were located far from central Bozeman. The $4/hr didn’t include fuel and other travel expenses. It didn’t include travel expenses incurred when I drove 30 miles for an interview. At what point did you realize you were gathering book-worthy material? When my friends started yelling, “You have to write a book about this!” every time I told stories about my experiences at dinner parties. I love how the book uses something as seemingly picayune as pet sitting to explore much deeper themes about where we live and how. What are the big takeaways for you regarding our relationships with our animals and the places we call home? Well, first let me say that I’ve noticed a trend: pets are now treated more as children than animals. The love-of-my-life dog, MooJee, lived with me for 15 years, but I never considered her my child. She was a beloved companion and, of course, I did everything I could to keep her happy and safe. She was dependent on me for that. But. She. Was. A. Dog. During my recent pet sitting adventures I noticed an increase in bad pet behavior. Lots of neurotic animals, made so, I believe, by their people. For example, I took care of two Irish setters whose daily schedule included cocktail weenies at 4:30 p.m. and an 8 o’clock bedtime. They also expected their lunch at 2 p.m. and acted out if it wasn’t served on time. By acting out I mean behavior such as opening the freezer and letting food thaw or dragging kitchen scraps out of the sink and throwing them all over the floor or hiding car keys under a dog bed. The places we (some of us, anyway) call home seem to be much more temporary than they were in the past. And people who have more than one house/home often leave their animals with a pet sitter while they live somewhere else for long periods of time or take pets with them and leave their houses empty. I wonder about all the huge, often uninhabited houses standing on Montana land, places that used to support wildlife, land upon which wildlife can no longer migrate or find food. What have you learned about humans through their pets? I’ve noticed an increase in the human need for external approval, which some people try to extract from their pets. Kind of crazy. Pet pics on social media attract lots of attention, which offers online validation for people. But of course, pet pictures and stories are entertaining and fun. We can’t safely post images of children online these days. Maybe our pets are stand-ins? And then there’s the amount of money people in the U. S. spend on their pets—nearly 150 billion dollars in 2023, according to Market Watch. So, your question is insightful. Are humans devolving as the status of pets rises? Are pets usurping control of our behavior and finances? What's next for you (wide-open question; I'm talking books, music, vocation, avocation, etc., etc.)? Ha! Thanks for asking. My mind is always blazing with new ideas. I just published another book, Do It in the Kitchen: a step-by-step guide to recording your life stories (or someone else’s). When they find out I’m an audio producer, people often ask me questions about recording audiobooks and oral histories, or want to know how to create a podcast. This book will help anyone who has those kinds of urges. I just finished writing a children’s book about a dog who saves his family from a house fire (true story). The process of finding an illustrator has been, well…interesting. I wish I had better drawing skills. (But maybe not because then I’d draw and I have too much other stuff to do.) My list of podcast clients has grown again during the past few months, so I do that editing/production work as it comes in. I’m also a musician and play in a band called Ukephoria Montana. We perform public and private concerts and participate in twice-monthly sing-along sessions at the Gallatin Rest Home. I participate in a songwriting collaborative and write songs on my own, as well. Every so often, I land a public speaking or workshop facilitator gig. I can’t name names, but I’m talking with an educational group about the possibility of producing a podcast series for them. It would be a dream gig for me. All fingers crossed, please. Since I’m self-employed, the marketing and PR tasks are endless. There’s always something new to learn. And, oh yeah, I read a lot of books and listen to several audiobooks a week. Yep, a week. Recent favorites:

What am I missing? What else would you like to say?

Oh, you are a brave man. I always have something else to say and usually say way too much. But I’ll stop now, except for this and this:

Wait! One more thing: Thank you for these questions and for reading my book. Oh, and another thing: I’m champing (yes, champing — to more precisely convey “impatience” — not chomping) at the bit to talk with you about your new novel, Dreaming Northward. Okay, that’s all my things. Maybe. But you should stop reading now. 2/7/2024 2 Comments Mind the LadderThere is a point to this, I promise, but I can't get there without first telling a sweet little story. So just bear with me, please... I've been contacting old friends on Facebook and other social sites, collecting mailing addresses. I'm having a literary reading and book signing this May in Texas, my first one in my home state in many years, and seldom does one get a chance to gather his foundational friends and acquaintances in one place and say thank you, for everything. I'm going to take that shot. The address search eventually led me to a man named Jim Fuquay, and that's where both the sweet little story and the point come in. Jim, an avid gardener, told me he was fighting the doldrums of February by reconnecting with old friends, that it had been a nifty little coincidence that I had reached out when I did. He asked me to give him a call, and I did, and let me tell you, it's been a long time since I enjoyed a half-hour as much as I did that one. But that's not the point. Jim was the first person to give me steady work in my first chosen field. It's been many years since that happened—thirty-five of them as of November of last year—and we both are, to state the obvious, much older now. We established on the call that he's eighteen years my elder (I honestly never knew the age gap, only that when we met, he was a fully mature man and I was...not). Eighteen years doesn't seem like that many now that I'm breathing heavily on age 54, but when I was eighteen years old and standing in his office, asking to be turned loose on writing newspaper articles, he sure seemed like an elder. An exceptionally kind and accessible elder, yes, but an elder just the same. Here's how I described Jim's decision to hire me in a public lecture I gave several years ago: The month before, I’d answered an ad in the Star-Telegram seeking correspondents for weekly community sections of the newspaper. I was eighteen, and the hiring editor wasn’t much interested in me until he read my clips. ... He gave me a job: the lowest-level, worst-paying, crappiest-assignment kind of writing job there was, but a job. Our deal was that I’d keep plugging away at school, he’d feed me a story opportunity every week or so, pay me $50 per, and let me build up a body of work. By late December...I had a story on the front page of the main newspaper. I was 18 years old, and I’d climbed a mountaintop of sorts. I wasn’t in the place I’d wanted to be, and I hadn’t made much headway into my half of the bargain with my boss, but I was getting somewhere. So many somewheres, as it turned out. During our phone call, I couldn't help reflecting on something that has crossed my mind plenty of times in my long working life, when I've considered how I got from there to here (and all the destinations in between): Jim didn't have to hire me. He could have given me a cursory look and sent me on my way, and his life would have been continued apace. Mine changed that day. A life has some number of true turning points, and that was one of mine. What Jim did that was so kind, so basic, and yet so uncommon is that he took a good look at me and imagined what I could be rather than fixating on what I was not. I was eighteen; I had no track record. I had only potential and gumption. Jim said yes to a kid who badly needed to hear that word. This is my point. And this is my plea: If ever you're in a position to take a gamble on someone, to surprise someone with a "yes" when you could save yourself time and aggravation with a brush-off, breathe that "yes" into the air. It could be the break that unlocks everything else for the recipient of that welcome word. I talk about this a lot with a friend with whom I lunch regularly. Where is the ladder anymore? What's a kid who doesn't emerge from the traditional mold supposed to do? What is a career and how does anybody get one?

When I was eighteen years old, in 1988, I was audacious in seeking a job, but at least I knew where to look. I had my eyes on a journalism career, and the procession into one was fairly well established at that point. You went to college. You gathered some experience. You did an internship. You caught on somewhere and started swimming. If you didn't read my public lecture, linked above, perhaps take a look now. I inverted that formula. More than that, I yanked it up by its feet and bounced it off its head. I bombed the college part, eventually. Internship? Never had one, at least not in a traditional sense. Experience? Not so much, no, not at that point. I came to Jim that fall bearing clips of stories I'd written for my high school paper. Not exactly a bastion of journalistic excellence. I came to him with chutzpah because chutzpah was all I had. Still, he said yes. He knew where the ladder was, knew he'd climbed it himself, knew the responsibility he had to make sure it was in good stead for someone else. He'd gained some latitude in his profession and spent some of it on me. A simple word, "yes," with fraught possibilities and potentially difficult outcomes. But what's the good of having a "yes" in your pocket if you're not willing to draw it out and slap it on the table? As we rang off, I thanked him for taking a chance back then. "I've never regretted it," he said. Neither have I, Jim. Neither have I. 2/3/2024 0 Comments Texas.I moved to Texas when I was three years old. No one consulted me, and I wasn't happy about it, but Texas and I, we found our way. In time, I came to view that move as the most consequential event in my life. When I left Texas for the first time, I was fifteen years old, about to be a sophomore in high school, and I made a snap decision that I'd like to live with my father in rural New Mexico. He'd just been through a divorce, a particularly bad one, and I thought maybe he needed me. It didn't take. A lot of lessons in that, some that got under my skin immediately and others that steeped for many years before I understood. Among the latter group, probably one of the most important lessons: You can't fix for someone else what he must mend on his own. By the end of December, I was back home in North Texas, where I belonged, even if I still felt the fit was a little tight. When I left Texas for the second time, I was twenty-one, and I pointed my nose toward just about the farthest-away dot on my map. I went to Kenai, Alaska, for a sports editor's job. That didn't take, either--though some vital friendships did—and I came scurrying back not six months later. When I left Texas for the third time, I was twenty-three, and it was a job I left behind, a fairly miserable nine-month stint in Texarkana. Texas and I, we were living together uneasily amid irreconcilable differences. I worked at night on the Texas side, then hustled back across the line to Arkansas to set down my head. When I had a chance to leave Texas, off to Kentucky I went. When I left Texas for the fourth—and, as yet, final—time, I was thirty years old and adrift, in the midst of one of those Worst Years Ever that seem to surface every decade. I'd bounced from San Jose to San Antonio, and I'd found Texas to be what it always had been: inscrutable, beautiful, alluring, interesting, and not for me. Back to San Jose I went, but first with a three-month misdirection in Olympia, Washington, and it's like I said: bad year. This is all to say that I've left Texas a lot. But Texas has never left me. The math doesn't lie. Texas had me for most of eighteen years, then nine months, then eight months. Nineteen and a half years, let's call it. Add in various visits over the years—can you really leave a place that harbors your parents and your siblings and your formative memories and some of the best friends you've ever had?—and the total still falls short of twenty years, but let's round it up. Fine. Twenty years of Texas. I'm fifty-three, and on the cusp of the next number up. The scales tip heavily toward everywhere else. Here before too long, Montana will sink its years deeper into me than Texas ever did. It already has more of my heart, more influence on my creativity, a bigger share of my identity. Still, Texas abides. Still, Texas claims me. Still, I claim Texas. Those holds are coming up through my work first, which means they're coming up in my memories. My latest work is drenched in Texas, even if most of it unfolds farther north. There was no way to imagine Nathan Ray, the central character of the ensemble, without first cozying up to the Texas I knew as a boy, then conjuring a backstory where the Texas he knows is a backdrop of pain and disillusionment and gifts he cannot yet see. It's in the next book—the one with a title in flux, the one that may emerge in 2025, or maybe '26—that Texas takes a star turn, a place both abandoned and returned to. Here's a snippet: Texas was gone, falling behind us a mile a minute, and I was relieved and scared all at the same time. You leave Texas little by little and then all at once, yes, but Texas is also a magnet—a big, southerly magnet pulling at everyone else in the country with myths and manufactured romance and jobs and cheap living and low taxes. You can get away, but can you ever really leave? My answer, beyond the bounds of fiction? It's complicated. You can leave, sure. But you come back. The only thing is, I've never made a return stick. But it's early yet. I'm still upright and breathing. In the foreseeable term, of course, I'm not going anywhere. I live in Montana, I love living in Montana, and the father with whom I couldn't live in 1985 really does need me now. He lives in Montana. As long as he draws breath, and probably longer, here I'll be.

But I can't quit Texas, and unlike the answer I'd have given you twenty years ago, I don't want to. It's in my head and my heart and my memories, and the last of those is the most essential ingredient in doing this thing I do. That, I believe, is why Texas seems so insistent these days, like a song that I can't get out of my ears. It's having its say in my work, and I'm making room for it there. Perhaps, in some future I cannot yet see, I'll make other accommodations for it, too. Occasionally, either not knowing my history or not caring, a friend or acquaintance will say something cutting about the place that shaped my boyhood, and thus my life. And I'll cringe, because the cuts are easy enough to administer when Texas serves up such ridiculous stereotypes, such a bloody history, such casually cruel politics. On a day when I can find patience and indulgence for a friend's carelessness, I will say, OK, yes, but Texas is also a vast and beautiful place, full of beautiful people who contain multitudes. Texas isn't made for anyone's tidy little box. It's destined to spill out from whatever attempts to contain it. In short, it cannot be seen in simplicities when its complexities abound. 12/15/2023 0 Comments 'It's Not the Trophy. It's the Game.'The title here is paraphrased from something I saw on LinkedIn. (For a whole different view of how I spend my days, hit me up over there.) It resonated for a couple of reasons. One, it was a different wording of an old concept, and that's always appealing. Second, and more important, I was a day removed from a six-hour stretch of standing in front of high school classes and talking to kids about the writing life. (Quick side note: Whatever your talents, whatever your field(s) of endeavor, I cannot recommend classroom visits highly enough. It's a chance to contribute, to give a teacher a much-needed respite, and to help give shape to students' possibilities beyond the classroom, a time that is coming up on them quickly and for which they're probably not fully prepared.) During my visit, I would start by introducing myself to each class and saying, yes, I wrote the book you just read (in this case, 600 Hours of Edward, which is on the approved reading list for Billings high schools), but I also do other things. At the time I wrote 600 Hours, I was a copy editor at the Billings Gazette. Later, I was a pipeline inspection specialist (a fancy title for pig tracker). Still later, I was a senior editor at The Athletic. Now, I'm an analyst for a research firm. I design Montana Quarterly magazine. I take on freelance editing and design gigs that interest me. I write novels and plays and sometimes even poems, although those are mostly bad. Those are a lot of different things, but they share one key commonality: They're not just ways to make a buck. They are things I do and things I am, and that manner of describing them is something I trot out regularly, because it's such a complete summation. That intrinsic sense of purpose and being keeps me focused through the vicissitudes and drudgeries of a workaday life. That work, whether for a salary or for the variable and uncertain recompense of royalties, can't just be about making a buck, necessary as that is. I told the classes that, yes, of course, I sometimes find myself wishing I had more time for the creative things I do. But the truth is, I would miss the payments analyst part of my life if I gave it up every bit as much as I'd miss the toil of writing a novel if that fell away from me. It is at this point that I diverge from some of the artists I admire most, who talk about the art-centered life in almost monastic terms. Or maybe I just use a different definition to arrive at the same idea. Art is at the center of my life, in that there would not be a life worth living without it, but it shares that space with myriad other things that constitute who I am and how I engage with the world around me. So ... the trophy and the game. Some people don't think they've made it until they've made it: until they've reached some perch, garnered some award, ascended to some income bracket, been elevated to some stratosphere. And, in some cases, reaching those levels is the test case for happiness. I think that puts happiness—a transitory quality anyway—in a narrow, often inaccessible place. The game—the process, if you will—is where the action is. Play the game hard and faithfully, however it's defined, and the trophies have a way of either showing up or making a subtle reveal of themselves as something you never imagined they could be. 8/26/2023 0 Comments Saturday Afternoon Craft Talk...

... if you'll indulge me:

The solitude inherent in composition is something I find absolutely indispensable to the experience of trying to write a novel. It might not be my favorite part—it's awfully hard to top the feeling of completing a first draft or holding the published artifact in your hands for the first time—but I cherish it nonetheless. If it were suddenly not a part of the effort, if writing became a spectator sport or, worse, if I were relegated to a minor participant in the whole endeavor ("AI, take a wheel"), I would just quit. Be done. The joy would be gone.

This is not to say that I believe the writing of a novel to be an iconoclastic endeavor. Not at all. By choice and habit and history, I'm alone on the first draft. The second. Maybe the third. But even then, even with those two words "the" and "end" on the last page, I'm far from being finished.

And this is where I start getting by with a little help from my friends.

Some writers swear by the workshop. If you've not experienced it firsthand, you've probably seen it in the movies. A pile of red meat in the form of pages is thrown to a group of other writers, who tear into it with equal measures of hostility and glee.

Who am I to argue? I didn't come from the academy.

I swear by the beta reader. This is someone tactically chosen to read a manuscript at a fraught point—for me, that's when I've done as much as I can do with it alone and still know in my heart I haven't done nearly enough—and provide actionable feedback on what works and, especially, what doesn't.

I choose different beta readers for different reasons, and though there have been repeat invitees over the years, the roster tends to change with the project. Three to five people, generally. Enough to get an accurate sample, to weed out the outlying sentiments, and a manageable enough number so I don't lose sight of what compelled the work in the first place. I never want to get separated from my own vision. I just want to be challenged so the work, in the end, is better. So I choose on the basis of life experience, temperament, wisdom, intelligence, and specialized knowledge about the subject matter of my work. I'm lucky to have many, many friends who fall broadly into those categories. I choose on the basis of someone's ability to separate herself from her own inclination for how to resolve something (that's my job) and instead simply articulate why she sees a problem. I've been very, very lucky in my choices for these roles. They've made my work immeasurably better. I simply couldn't do it without them.

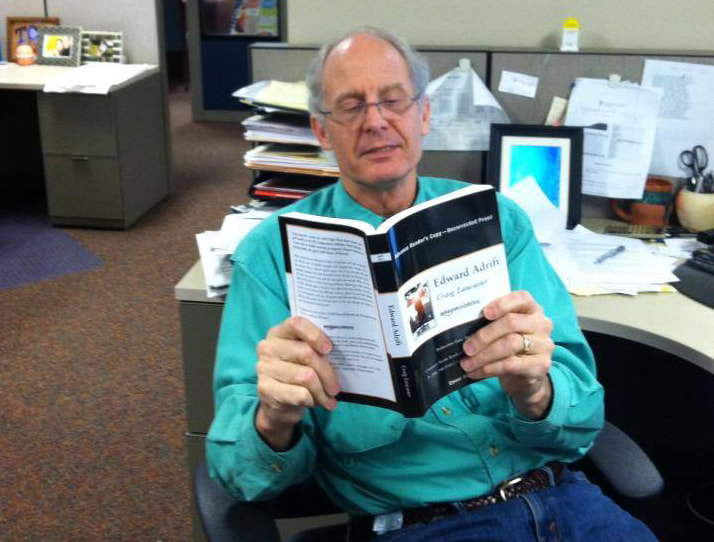

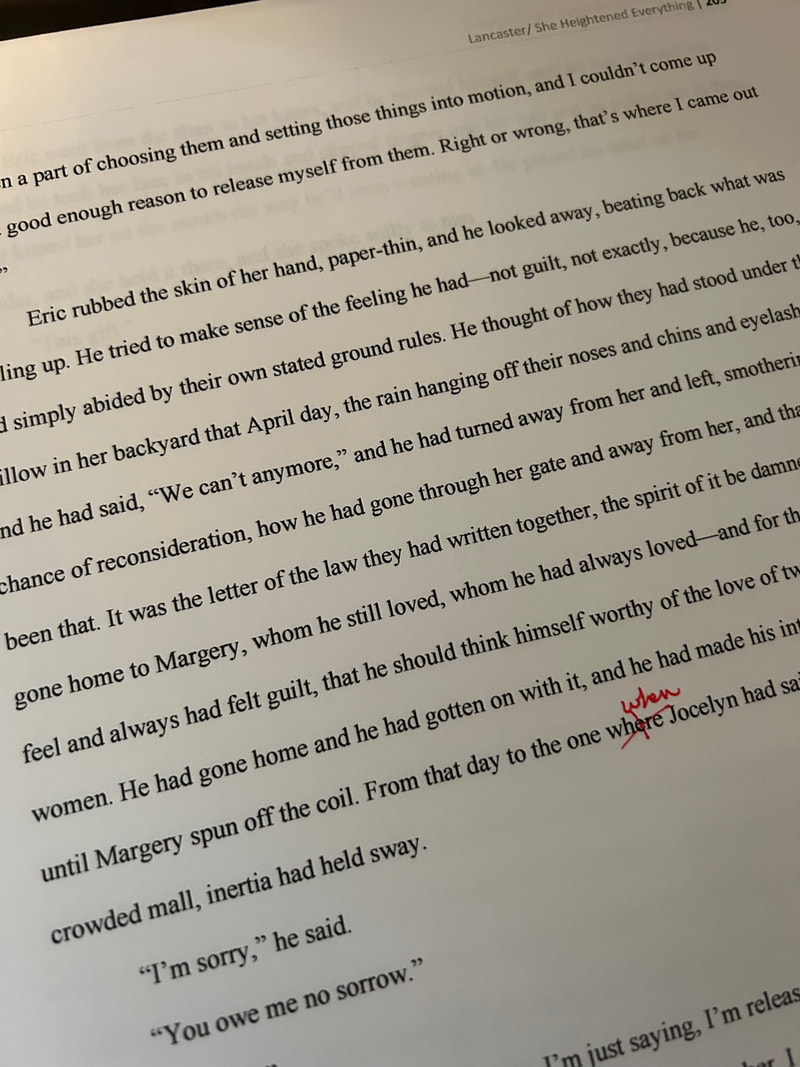

I was thinking of this today when I finally got off my duff and picked up the manuscript I'm calling She Heightened Everything, after the printout has sat for months on my office table. (You can see a snippet of it above.) Several weeks ago, one of the beta readers I asked to participate sent me her feedback, and man, was it extensive. Like I said, I've been very, very lucky.

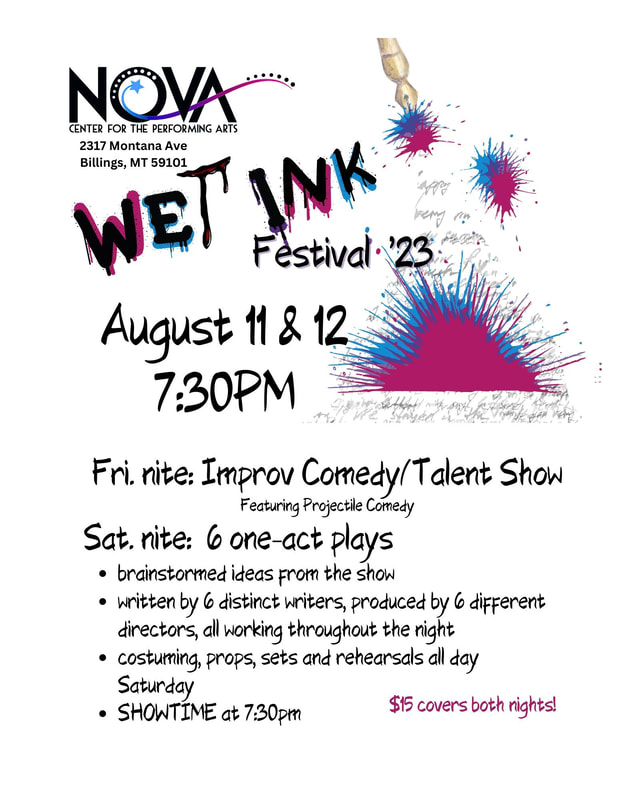

Almost all of it was useful to me, but even that couldn't overcome my hesitation to re-engage with the manuscript. I've been preoccupied with a new job, other creative endeavors, and uncertainty about when the book in front of it is going to at last be published. (I think we'll have an answer soon.) She Heightened Everything has felt so far away from my immediate range of concerns that I've simply been unwilling to dredge it off the hard drive and get moving. But today, I felt differently about it. So I set my shoulder into it and started working through my beta reader's laundry list of concerns. I'm not through everything, and there are some things on which we simply disagree (this is inevitable and natural and fine), but I'm back in it. She's making my work better. I don't know when you'll see it, or if you'll see it, but it's better today than it was yesterday, and that's everything. Thanks, Courtney. I owe you, big time. 8/18/2023 0 Comments We Love the Stage*As I write this, I'm nearly a week out from one of the most extraordinary creative experiences of my life. On Friday, Aug. 11, after watching a talent/improv show and getting writing prompts from that, I and five other writers hunkered down at NOVA Center for the Performing Arts in Billings, Montana, and wrote six original one-act plays. We had less than 12 hours to finish our work. After that, six directors and cast members handled rehearsals, costuming, and the construction of sets. On the second night of the Wet Ink Festival 2023, those six one-act plays were presented. It was pure exhilaration, from start to finish. I marveled at the talent all around me—the writers, the directors, the performers, the indefatigable nature of our organizer, Gustavo Bellotta. The audience that showed up to celebrate with us. I entered the weekend having serious doubts as to whether I had the stamina for such an endeavor. I left wanting to do it again. And again. Some time back, I added a Plays section to this website. I'm hesitant to claim the mantle of playwright, but I'm also determined. Two of my one-acts have now been staged. I expect news soon about bigger things. Mostly, I'm just so thrilled to learn more about how to do this and give my storytelling another outlet, one that's very much complementary to the solitary nature of writing novels. As I wrote on Facebook, part of the joy—and the melancholy—of Wet Ink is that creation bloomed in one evening, was presented in another, then was gone with the wind. These plays will probably never be presented again, at least not in the form they took last weekend. Maybe someone has a bigger idea that will grow out of that one act. I think my play, titled Your Mouth Is Moving a Lot, is probably one-and-done. But the shows must go on. Our host for the weekend, NOVA, has a long-term mission of bringing high-quality performances to Billings. To help with that in a modest way, I'm selling digital copies of my script for $3. All net proceeds get turned over to NOVA. If you're inclined to help, you have my gratitude. *—from the song of the same name by the Pernice Brothers.

5/15/2023 1 Comment Dan GenselFriendships are funny things. Sometimes, they exist in a fixed place and time, sturdy and strong for a particular period in our lives. A counselor of mine, Jane Estelle, once told me that human relationships are often like cab rides. They have beginnings and ends. That was wise. It's true. Sometimes, though, friendships are a ride that never ends. You don't reach a station and get out of the car. You keep going, through years and locales and jobs and other relationships and seasons of your life. And sometimes they are both. They are fixed in time and endless. Those are the best friendships. Dan Gensel was that kind of friend to me. Dan Gensel is gone. I moved to Kenai, Alaska, in November of 1991. I was 21 years old, and I didn't know anybody there. I'd come from my hometown, North Richland Hills, Texas, and had taken a job as the sports editor at the Peninsula Clarion newspaper. Why? Why not? I was 21 and unencumbered. Alaska was far away. I wanted to go and could go, and that's a combination I wasn't always going to be able to put together. Now, for example. Couldn't do it. Won't do it. Want-to isn't even a factor. Years ago, I wrote a piece for the radio program Reflections West about that time in my life and the factors compelling me to move north. You can listen to it here. My first week in Alaska, I covered a Kenai Central High School-Soldotna High School girls basketball game. It featured two of the best players in the state, two of the best players in the history of the state: Stacia Rustad of Kenai and Molly Tuter of Soldotna. On one sideline was Coach Craig Jung of Kenai, a man I'd come to greatly admire in my brief time there. On the other sideline was Coach Dan Gensel. He and Craig were great friends and ardent competitors. Stacia and Kenai were coming off a state championship; Molly and Soldotna would win one a year later. I didn't know any of that. I was just a new-in-town sportswriter, trying to figure things out. The photo above, of Dan and Melissa Smith, one of the kids I covered that season, isn't from the game in question, but it's a good approximation of the Dan Gensel of my memories. After the game, which Kenai won, he sat in the bleachers with me and just talked. Where you from? How'd you come to this job? What's your background? Getting-to-know-you stuff. I liked him, right from the start. Later, I met his wife, Kathy, and his daughter, Andrea, and liked them, too. In time, it became love. But it was like, from the get-go. Those were lonely days for me, 4,000 miles from home, alone, barely scraping by, driving an on-the-verge Ford Escort and living in a one-room apartment. Dan and Kathy took me out for my 22nd birthday, just a few months later. Dan gave me seats on school buses to far-flung tournaments and let me sleep on his hotel room floor sometimes when that was the difference between my being able to cover something and not. He also gave me a basketball education, one I tucked away, then unveiled when I wrote a short story about a wunderkind basketball player and a coach and a town that loses all sense of proportion. Here's an excerpt from Somebody Has to Lose: “Mendy, it’s like this.” He squared up to the basket, squeezing the ball between his hands and planting a pivot foot. “First option: jump shot.” Into the air he went, releasing the ball at the peak of his jump and watching it backspin softly into the net. Cash, her face red, gathered the ball and rifled it back to him. “Second option: drive.” Paul took two dribbles into the lane and then fell back to his spot on the periphery. “Third option: make the next pass.” He slung the ball to Victoria Ford, directly to his left on the wing. “You know better than to just throw the ball over without even looking.” Paul turned to the players clumped on the sideline. “Shoot, drive, pass. When you get the ball in this offense, that’s the sequence. I don’t want anybody not following it, you got that?” Yes, sir,” the girls answered glumly. "You get the ball. If the defender has collapsed into the middle, you shoot the open shot. If they’re crowding you, drive around them. If you’re covered, make the next pass. This is not difficult. Run it again.” That right there, in just a few paragraphs, is the Dan Gensel philosophy of basketball. It inverts the conventional wisdom of the time—pass first, shoot later—into a kinetic, high-scoring, fun way of playing. And, man, was he ever successful. Won a lot of games. Won a state championship. Made the hall of fame. But that's not what I remember most about him. I remember that he and Kathy and Andrea became family, particularly after I came back to Alaska in 1995 for a three-plus-year stint at the Anchorage Daily News. I remember that I was a regular guest on their downstairs couch, so much so that it developed an imprint of me. I remember that they tolerated movie nights when I'd make them watch Ed Wood and Pulp Fiction, fare that was decidedly not up their alley. I remember later visits in California and Las Vegas. I remember Andrea's wedding in the early aughts down in San Diego, when Dan asked me to give the speech before the father's speech. Predictably, I went for funny and warm, extolling my love for a family and a young woman I'd watched grow up. Dan, after me, had everybody in tears with his love for his little girl. Later, in a quiet moment between us, Dan said, "I knew you'd take them one way and I'd bring them back the other." Teamwork, baby. I remember Dan's closing out the wedding reception by climbing atop a table and lip-synching "Don't Stop Believing." I hate that song, but I love that man. I remember, a few years later, Dan's serving as the best man at my first wedding. The marriage didn't last. The friendship endured. I remember all the times we talked about getting together over the past decade or so. I remember that we didn't make it happen. That'll be the only thing I regret. It's like I said: It's a friendship fixed in time and eternal. I'll carry it now, for however long I'm around. There's been a lot of that these past few years. Too much.  It's been a long while since Dan was a basketball coach. In his final years, he was a sports radio guy--a damned good one—and a grandpa, a role he made his own in an inimitable way. He and Kathy became community stalwarts in Soldotna. Andrea and her husband, Lee, are right there. It's been a good life. It will continue to be a good life, I'm sure, but those who love Dan will have to live with a big hole in it. It's a testament to the community Dan helped me build thirty-odd years ago that one of his former players, someone with whom I've been close since I was a 21-year-old green sportswriter riding a school bus, contacted me with the news. I spent just six months in that job at the Peninsula Clarion. My Facebook page is full of people I knew then and still know now, and I'm a lucky boy, indeed. Dan was 34 when I met him and 66 when he died, and that's both a long time and not nearly enough of it. I'll miss him. 11/8/2022 0 Comments Books for Our* KidsIt's Tuesday, November 8, the first snow day of the season in Billings. Ordinarily, I'd have stayed in, but today I went out, and I'm glad I did. I delivered 40 fresh new copies of my debut novel, 600 Hours of Edward, to Skyview High School in Billings. That was the last of four deliveries I've made to Billings schools, for a total of 150 books. And the beauty of this is that I am merely the messenger, the delivery driver. These books—to replenish previous (and tattered) copies of the novel that have been in the schools for around a decade—landed where they did because of a community that answered the call. I asked for donations, enough to purchase those 150 books at a steep discount from the publisher, and my community funded the campaign inside of 12 hours. And when I say community, I mean Billings—so many people in Billings—but I also mean the larger community I'm privileged to call my own. Teachers in Virginia kicked in donations. A coworker in Ohio ponied up. Friends in Texas. People I didn't know until some cash landed. They did this because I asked for help in putting books in kids' hands. In this strange time in America, when we hear so much about taking books away from kids, these generous donors put books in front of them. It's a beautiful, radical act. As I so often do when the subject turns to the ties that bind us, I give thanks to teachers for doing what they do even as a significant slice of the population wants to fight them, deny them what they do well, castigate and smear them. This is shameful, yes, but it's also not new, and we can either let these angry, outsized voices have the floor, or we can meet them with a different set of values. English teachers where I live were instrumental in getting 600 Hours on the approved curriculum reading list for the high school level here in Billings. They saw a contemporary story of a neurodivergent character, one set in the town where their kids live, and they did the heavy lifting to ensure that they could teach that book in their classrooms. As I said in the Billings Gazette article about the first book delivery—thank you, Gazette—those teachers' dedication puts a responsibility on me that I'm only too happy to carry. “They’re the ones who pushed for this book because they know how to reach these kids. And if they’re the ones who are making sure of that, I’ll be the one making sure they have the books.” Damn right. A word about the asterisk up above.

Yeah, they're our kids. I sometimes get a lot of pushback on this—"they're not my kids"—and I really wish someone taking the opposite view would spend just a little bit of time thinking expansively about the idea and the implications of abandoning it. My trip through public education was, in many ways, a disaster. It was also one of the most important factors shaping who I became and how I see the world. Certainly, public education is not perfect, and certainly, reasonable people can disagree on how to shape it, fix it, whatever. But we cannot, must not lose our responsibilities to ourselves and each other and the generations coming up behind us. Public education is a compact, an agreement that we will provide our kids with a basic education, as a community, knowing full well that our investments in those kids now are really an investment in our own future as a society. If we lose that, I'm afraid we lose everything else. So, today, I finished delivering some books. Backed by my community. Hopeful that the fight can be won. Determined to keep fighting, either way. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed