|

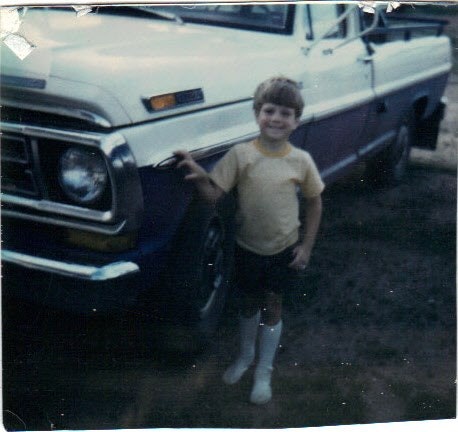

6/30/2021 2 Comments They're Leaving Us Searching the cabinets in Casper, Wyoming, when I was a little boy. Searching the cabinets in Casper, Wyoming, when I was a little boy. It was after Ned Beatty died—which came not long after Gavin McLeod died, which came on the heels of Charles Grodin's death—that my friend (and best man) Jim Thomsen said, via text, "We're losing the generation we looked up to." Indeed, we are, as early Gen Xers, and there's a reason for that: We've made a right turn at middle age and are headed not away from Albuquerque but toward our own burning out. If people twenty and thirty and forty years our elder are finding the exit of this mortal coil, it's only proof that time is immutable and undefeated. We will follow them into stardust, and that eventuality is already close enough to whisper to us. My reply to Jim that day: "Dying is the one thing we were born to do." I've been thinking of that a lot—not necessarily Jim's observation, nor mine, but the relentlessness of time. It's not sentimental. It's not personal. It's not tender or caring. It just is. Every fraction of a second of every second of every minute of every hour of every day of every week of every month of every year... I've also been thinking of it a lot since finding out that my Aunt Barbara died last week. If there's someone who has been in my life from cradle to now, my parents aside, it is her. An early friend of my mother and father. The sister of my eventual stepfather. The mother of cousins, once and twice and thrice removed. I've been driving for thirty-five years, and many of those years have seen me drive into or through Casper, Wyoming, the first home I ever had, just a few houses down from where Barbara and her family lived. And almost every time, I've made a stop to see Barbara, and before that Sammy, her late husband. It's a ritual that seems inseparable from what I know to be the way of my life: If I'm in Casper, I swing by and say hello. There will be no more of it, at least no more that terminates at her front door. Time is not sentimental, but I remain so. I might still turn right off Poison Spider Road. I might still cast a glance left at the first house I ever knew. I might still wonder what my long-ago friend Richard is doing these days. I might wave at Barbara's house as I go by. But go by I will, because there's no longer any reason to stop and say hello. It's hard to part with that. Hard for me, anyway.

2 Comments

6/25/2021 0 Comments The Things That Need to be Said

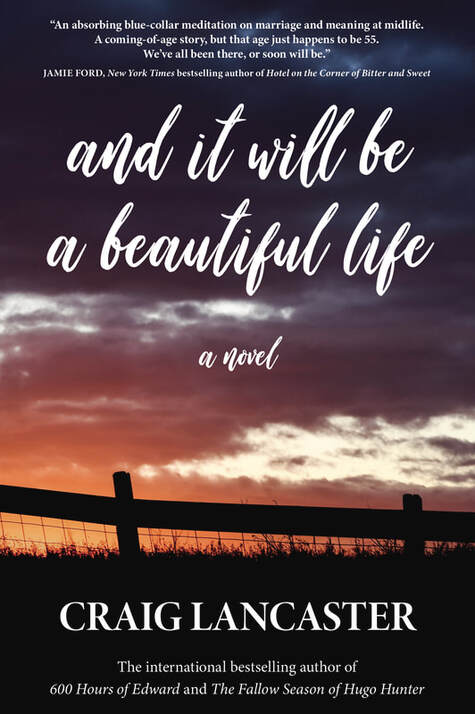

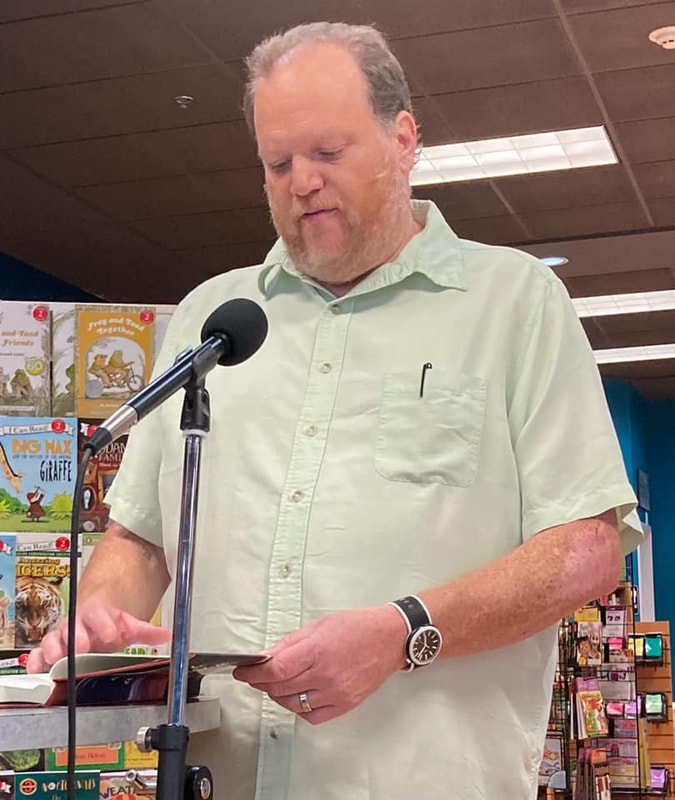

After the second reading from And It Will Be a Beautiful Life last weekend at This House of Books, I was talking about the prominent roles of memory and reflection in writing, and I relayed the story of reconciliation with a former college roommate whom I wronged more than 30 years ago. The video above begins with the salient part.

The brief retelling in the video covers the major points. I ruined a good friendship with selfishness, and I left him holding the bag on what was supposed to be a shared obligation (rent). We never talked again after I bailed, and that sucks—the bailing and the not talking. It was not a proud moment for me, and occasionally, the memory of it has drifted through my head and shamed me anew. And I'll just say this: The occasional shame was a reasonable toll for the way I inflicted my immaturity on someone else. A few years ago, the woman who ran the student publications department at UT-Arlington, Dorothy Estes, died, and tributes poured in from all over, including one from my former friend. Long after I should have done so, I reached out: Seeing your lovely remembrance of Dorothy Estes brought forth a lot of memories, many good, some bad, and the bad ones all on me. I've thought about you from time to time these past 25-plus years. It may well be ancient history, but it's something I've left undone, so if you'll indulge me I'd like to close it up now: I'm sorry for the way I left you holding the bag on that apartment all those years ago, and for the way that effectively ended what had been a good friendship. It's been a source of shame and regret for me for many years, as well as a point of departure. In the aftermath of that, I started growing up, which was long overdue. I was telling my wife about those years this morning. The Shorthorn, and UTA, don't occupy the same place in my history as they do for so many who've come together to remember Dorothy. Those were difficult years for me—difficult in my own skin, in my studies, in owning up to the responsibilities of being a man in the world. I found my way later on, but I've certainly harbored regrets for the prior mistakes and idiocies. Again, I am sorry. I hope this finds you well. I loved your remembrance. It evoked in me something I remember often feeling when I read your stuff all those years ago: Damn. I wish I'd written that. What he wrote in response belongs to him, but I can assure you it was kind and considerate and reflective of the young man I knew him to be and the older man he'd obviously grown into. We closed the book on something between us, and I think we both felt good about that. One of the things I've learned about myself is that I crave closure, and that yearning can be good and bad. On one hand, the compulsion allows me to reconsider past encounters rather than just calcifying into positions that might not be healthy. On the other hand, sometimes situations are meant to be exited wordlessly and expediently, a true change of trajectory. Wise words from a former counselor of mine, as I walked through the rubble of a divorce: "In some things, closure is overrated." In this case, though, I think it's just what the moment required. For both of us.

Here, though, is where the story takes a turn …

I went home that night after the reading and reflected again on the original unkind act and on the subsequent, many-years-later reconciliation, and the next morning I sent my erstwhile friend a copy of the video above, pointing him toward the bit about our history. And then, for whatever reason, I ran a Google search on him. Roy R. Reynolds, my long-ago friend, died earlier this month. Fifty-three years old. Young. Far too young. I feel privileged to have known him, once. Regret for not mending the breach before we did. Gratitude that the mending happened at all, that I reached out, and especially that Roy met that outreach with grace. He didn't have to do that, but he was the kind of man who wouldn't have done anything else. Godspeed. 6/20/2021 0 Comments We're Back! (Thank Goodness)

The fears and hesitations of the pandemic have been myriad—what if I get sick or die or can't work or, or, or…—and yet as I didn't get sick or die and kept right on working, the things I missed most, holed up in the house, were human and artistic. How I longed to go to a badass poetry reading. Or a play. Or a concert. Oh, how I took those things for granted before COVID-19, and oh how I never will again.

On June 19, about 10 days into the life of And It Will Be a Beautiful Life, we had a couple of events at This House of Books in Billings to mark its birth. What a day it was—the gift of fellowship, of seeing people I haven't seen in years*, of hugging necks and reading from this new work. I missed it so much. I think it's been at least two years since I've done it. And now, I can't wait to do it again. *--We moved back to Montana from Maine in April 2020. Right in the middle of the pandemic. There are people I love whom I haven't seen in these past 14 months, and some of them, at last, I saw at This House of Books. I tell you, I would have cried if I hadn't been so busy being grateful. 6/16/2021 0 Comments Shuffling off to Buffalo It's no secret at all that the protagonist in my new novel, And It Will Be a Beautiful Life, a pipeline inspector named Max Wendt, was conjured from my own background as an occasional pipeliner. (Where it all flows from there, of course, is more fiction than fact, more imagination than recitation. But stories gotta start somewhere, and as I've written before, mine start in the memory banks.) Early on in the book, Max heads off to a job in Buffalo, N.Y., and an assignment he doesn't relish: He's asked to train a new worker on the crew, a 30-something woman about his daughter's age, and what happens from there has a great impact on Max and on her. (If you're thinking here that surely I went for the easiest of tropes, the kind of trope middle-age male writers have been committing to the page for as long as there have been pages, please consider it might have gone another way. Because it did.) But the true love letter to Buffalo, the place and the idea, comes from a third character, Charles Foster Danforth, an odd man Max meets in his travels. The two men aren't well acquainted at that juncture, but they're working their way around each other, and Charles, via email, urges Max to show more appreciation for the places he gets to go: Do you realize where you are? In architectural terms alone, you’re in a place that changed the game, particularly with the buildings that went up between the Civil War and what my grandfather, Preston Foster Danforth, the old scamp, called the Great War, even if that moniker was eventually usurped by a greater war that came along. (This, Max, is the folly of our human condition. We are terrific at war. We are less terrific at things that would be better for the collective us. But I digress.) I wish I had the time to go back there. It would be charming to see you, of course, but I think I would leave you to the pig and go walk those radiating boulevards downtown (I bet you never thought of Buffalo and Paris as comparable, but there you go). I’d see the buildings of Wright, of Richardson, of Sullivan, of Mori, and my day would be spent before I even got to the art galleries or the wine—yes, my friend, the wine; you take the chicken wing, I’ll take the pinot. I loved writing that bit. Because I love Buffalo.  I'm going back to western New York in the coming week. It's been a while, what with the pandemic and moving back to Montana from Maine amid it. The food experience there is basically inseparable from the rest of it, so much so that one of my dearest friends, a guy who grew up in Orchard Park, N.Y., calls it "a great fatboy town." I've certainly added some pounds there over the years. But it's more than wings and hot dogs (Ted's—oh, god, Ted's) and fried bologna sandwiches and some of the best pizza you'll ever eat. Buffalo was a great notion, a triumphant city in the 19th century, the location of a shocking assassination, a place that hangs in there, that keeps punching. In my own narrow experience, few cities can match it for general friendliness—it's not uncommon for me to find myself in neighborly conversation with locals when I'm out and about; indeed, the uncommon thing is when that doesn't happen. Buffalonians persist. They push on toward better days. It's the best we can do sometimes. So, about the book ...

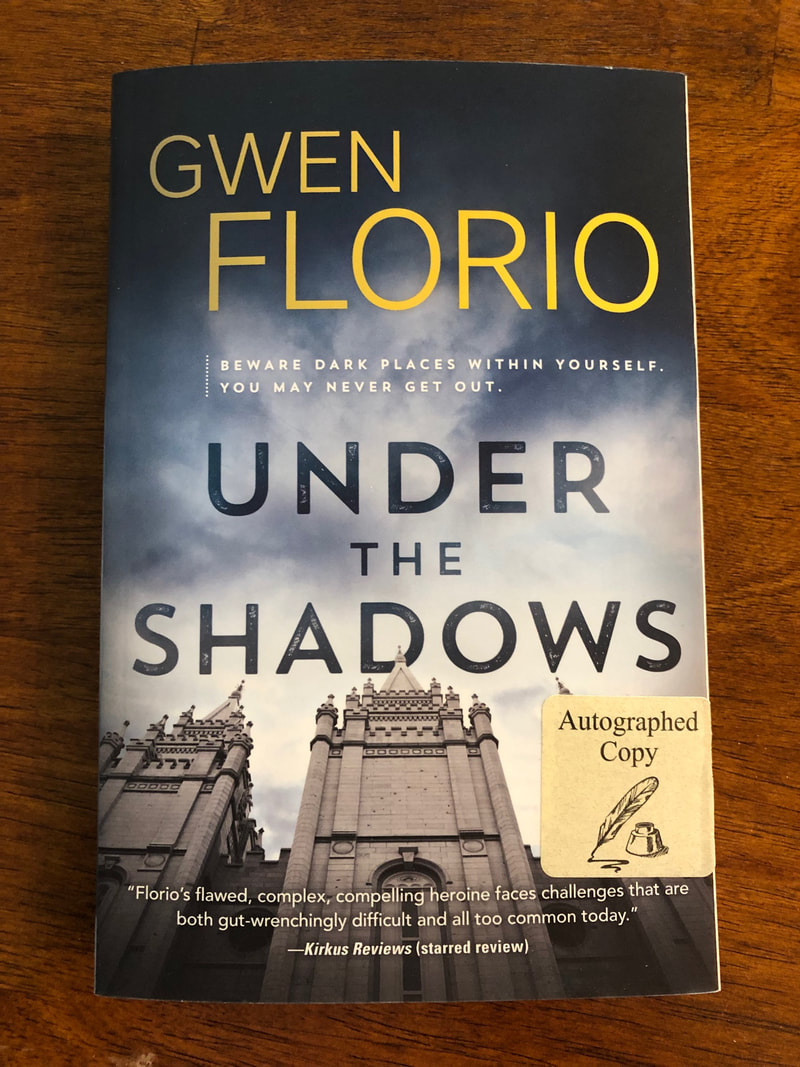

I'm doing two readings at This House of Books in Billings this Saturday, June 19. They're at 1:30 and 6 p.m., and they're the first live events at the bookstore since the pandemic began. Billings is my home, and This House of Books is my home bookstore, and I'm thrilled to help usher live readings back into the community. We've missed them. I've missed them. It's good to be making a comeback, and I look forward to all the coming readings and plays and concerts, things I took for granted before last spring and never will again. If you're close enough to come, I'd love to see you. The bookstore is limiting attendance at each reading, requiring masks and enforcing distancing. It's only sensible. Call if you'd like to join us. 6/11/2021 0 Comments How to Spend a Day in Montana** — one of an endless number of permutations 9:50 a.m.: Head out of Billings due west with fair Elisa. Destination: Livingston, 117 miles down Interstate 90. There is much I could say about Livingston, although it would be nothing that hasn't been said before by better observers with keener insights. I made a friend laugh earlier today by calling it my Emergency Backup Montana Hometown. That's how I feel about it and the people I encounter there. (It was good to see you, Marc Beaudin. It's always good to see you.) 11:45 a.m.: Meet Kris King for lunch at Neptune's. In my early days of designing Montana Quarterly, Kris—one of the magazine's steady contributors (she does the author interview each issue)—gave me shelter on my overnights to Livingston for final magazine production. She's a whip-smart, offbeat, fun, funny, wonderful friend who has been extraordinarily kind to us, and it was the first time we'd seen her in more than three years. (We moved to Maine. We moved back. There was/is a pandemic.) If you've read my short story Remember Me in Istanbul, you might remember the ex-girlfriend's house that a guy and his wife let themselves into on a winter night. I modeled that house, and the spirit within it, on Kris' place. Now you know ... Around 12:40 p.m.: Head a few blocks over and get a sneak preview of the forthcoming Edd Enders Retrospective. (June 18-19 in Livingston, and you should totally go if you're within driving distance.) It's one magical thing to be able to stare deeply into a single Enders work, which we're fortunately able to do every morning, as one adorns our bedroom wall. (I mentioned Kris King and her kindnesses; the painting below is one, a wedding gift that we treasure.) It's quite another to see canvas upon canvas, crossing all eras of his wonderful work. What a thrill for us. Around 1:15 p.m.: Head out for Bozeman, another 26 miles west. We ended up at the Emerson Center, a place I'd often heard about but never visited. There, I dropped off a copy of And It Will Be a Beautiful Life to Rachel Hergett, one of Montana's premier writers about the arts. It was our first face-to-face meeting, another unfortunate byproduct of the pandemic. Can't wait to renew acquaintances again and again. I'm telling you, there was a buoyancy to the entire day in this regard. We're opening up, and hope is flooding in where darkness once settled. I'm allowing myself to dream of literary readings and concerts and sporting events and dinners with friends. Around 2:45 p.m.: Two more stops, both essential. First, Country Bookshelf, one of the finest bookstores you'll find anywhere. What a wonderful feeling to see the new book paired up in the window with Sweeney on the Rocks by Allen Morris Jones. Allen and I are doing a virtual event hosted by Country Bookshelf on June 30. We'd love to see you. And then to also see it on the shelves ... I also scored a Gwen Florio novel. Signed. Who's the lucky kid? Finally, no trip to Bozeman is complete without a stop at The Baxter and the little chocolate shop in the lobby, La Châtelaine. Elisa had the Hawaiian red salt caramel truffle. I had the French martini truffle (below). We split a Meyer lemon truffle. No regrets! After that? Eh, there's not much to report. Just a 143-mile drive through some of the most beautiful countryside there is, pulled along by the mighty, north-flowing Yellowstone River, a ribbon to guide us home. In the best iteration of myself, I try to be grateful for the life I have and the way I'm able to live it, but circumstance and the intrusion of transient difficulties sometimes get in the way. Perfectly natural, of course, but also something that can swallow your perspective if you let it.

Today was all gratitude all the time. For this life, for this place, for these friends, for these adventures, for the next bend in the highway ... 6/10/2021 0 Comments It's Out. Now What?My ninth novel, And It Will Be a Beautiful Life, flew the coop earlier this week, and I couldn't be happier. It's a beautifully produced original hardcover (my first), it's 352 pages of my beating heart, and I'm proud of the work I did on it. Though this is my ninth novel (and 10th book overall), in many ways it feels like my first. I broke with my longtime publisher a few years ago—nothing scandalous or rooted in hard feelings, just a parting of ways that happens in publishing and in life—and last year joined up with The Story Plant, the kind of small, attentive, scrappy, excellent publisher that's a wonderful fit for me and my work. I'm so pleased with the association. We are a good match.

So this book, in many ways, is the beginning of Act 2 for me. Whatever it's going to be. I'm going to give it everything I have. I feel as though I have a lot of work yet to lay into. One thing I plan to do—to whatever extent time, responsibilities, and the pandemic residue allow—is travel with this book, in the broadest possible definition of the word travel:

Eventually, of course, I have to find my way back to the desk. One of the truths of writing and publishing is that a new book out in the world is an old book in terms of the effort expended to get it there. I loved everything about the experience of writing this book and seeing it evolve into a finished artifact. And yet, a new journey ever beckons. I'll be on that road soon ... 6/10/2021 0 Comments Time. Speed. Distanced.Originally published April 3, 2021

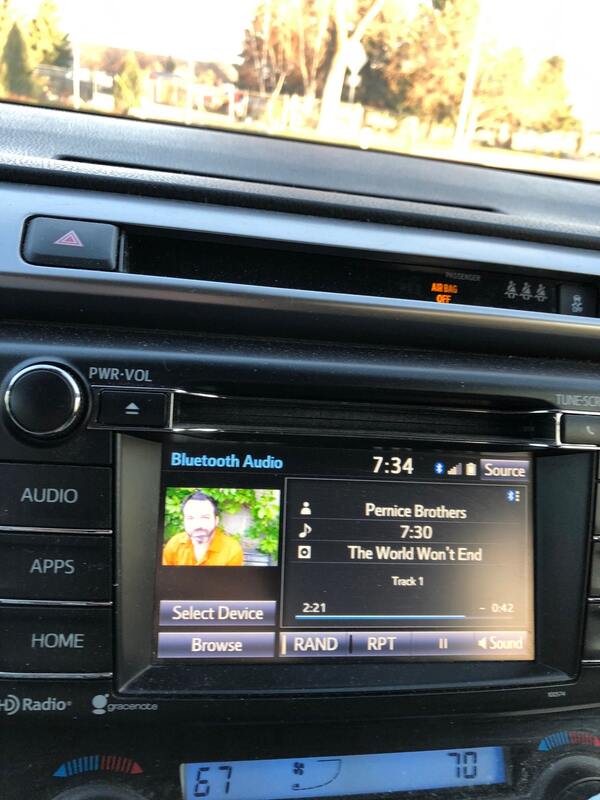

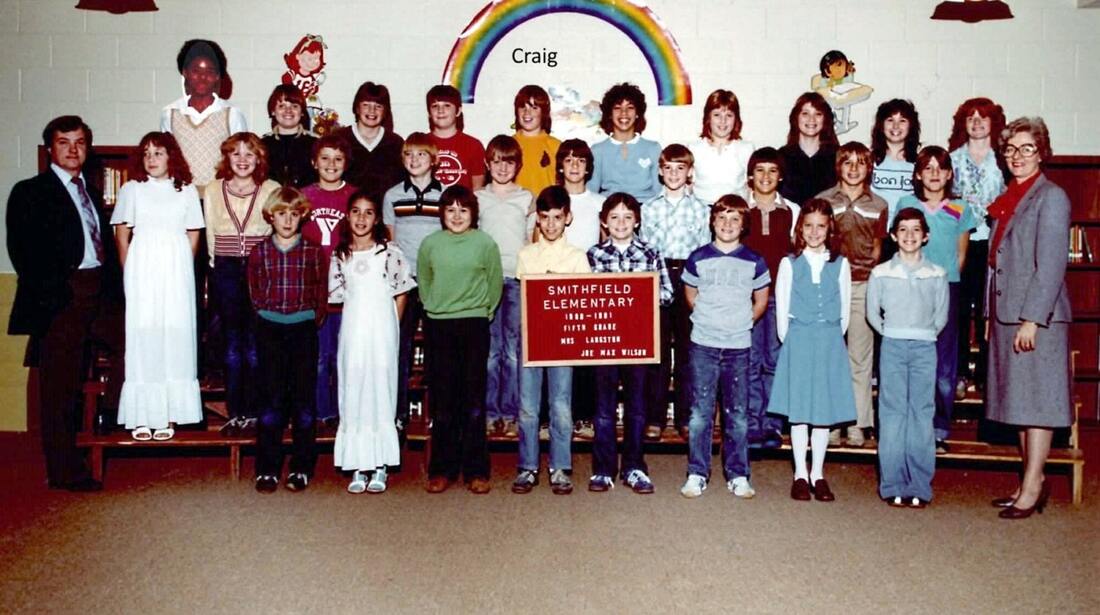

When I started writing these dispatches, I envisioned them as something of an occasional travelogue, seeing as how I’m an occasional traveler and how those occasional travels generally take me to places with not much resemblance to most conventional definitions of “exotic.” But my creative kryptonite—or maybe it’s my superpower—is that what I envision and what I end up doing are often wildly different things. These little notes that I’ve faithfully flung into the email in-boxes of whoever has asked for them have ranged wildly. Travel has been an incidental topic, in part because travel has been an incidental thing during the pandemic. So here’s the thing: I’m vaccinated now. My parents are vaccinated now. And because it’s been nearly two years since I’ve seen them, it’s time to mend that long rupture. I’ve written this before, and with nearly 800 miles standing between me and my folks tomorrow, I believe it even more fervently now: If you’ve been fortunate enough to survive this pandemic, if you have a roof over your head and food on the table, you’ve still been robbed of something: You’ve lost time. In the long bend of their lives, my parents have much less of it in front of them than they do behind. In the bend of my life, a generation shorter, the same is true. As Davy Crockett said, you all may go to hell; I’m going to Texas. My pup is coming with me. My wife, soon to stanch the bleeding of time with her own mother in New York, is keeping the light lit at home for my return. Per Mapquest, it’s 539 miles from my driveway in Billings, Montana, to my aunt and uncle’s driveway in Erie, Colorado. If you include, conservatively, two miles for meanders in Sheridan, Wyoming, and Douglas, Wyoming, as I sought out meals, it comes to 541. I started driving at 7:34 a.m. (Four minutes earlier, and I’d have been in perfect alignment with the first song already playing in my iTunes queue. The second song, randomly generated, suggested this could all take a while.) I pulled up to the house in Erie at 4:12 p.m. That’s eight hours and 38 minutes of travel time. That’s 62.664 miles per hour, on average. No wonder it felt like Wyoming would never end. I like to kid Wyoming, but that’s only because it was my first home and because it so perfectly fits a line that I pilfered from someone else. The great Peyton Pinkerton, guitarist for the Pernice Brothers, called Connecticut “the state in my way.” Anyone who’s traveled between New York and Massachusetts gets it. That’s how I feel about Wyoming. If you’re traveling north to south, it starts out promisingly enough, with the Bighorn Mountains and Sheridan—a beautiful, fun town by any measure—but the thrill is largely gone by the time you get to Buffalo and interstates 90 and 25 (you’ll be taking the latter) split. The thing is, the whole route is seeded with memory for me: my first home was in Mills, a bedroom community of Casper, and I have sepia-toned recollections in all of those towns, little snippets that I’ve tucked away that don’t always connect with larger memories. Buffalo heads on hotel lobby walls. Motels where I’d live with my dad when he was working. One of my early multistate solo driving trips as a 19-year-old. “Western identity” is the kind of thing you could fill volumes trying to pin down—and many have—but in large part, to whatever degree I have one, it’s rooted in that ribbon of highway that connects my first home with my chosen home. Snow fences, junkyards, tumbledown rest stops, gas stations where I’ve filled up dozens of times, fields where my father worked, fields where I’ve worked. It’s a part of me. I’m a part of it. But, yes, good lord, when your horizons lie beyond Wyoming, you start to wonder if you’re ever going to punch through to the other side. And then you do. Fretless is a good traveler in that he’s quiet and not restless. But he’s also obstinate. He wouldn’t drink for me, not a drop, but finally, in Cheyenne, I caught him taking a sip from his bowl in the cab while I was gassing up. As long as it’s his idea and not mine … Also in Cheyenne, while I was walking him, an unleashed, much bigger dog tore out after him. I had time just to get him into my arms and begin to wonder what I’d do if the unleashed dog turned out to be vicious. He wasn’t. The owner was apologetic. Which counts for something, but not a lot. It’s been a tough day for my intrepid pup. He watched me pack out most of his belongings and didn’t know what to make of that. He didn’t sleep a wink on the drive, which is unusual. I think he still suspects I’ll leave him. Ain’t gonna happen, bubba. We’re in a strange house (to him) with strange people (to him). Long day tomorrow, and I can fill him in about how Aunt Linda and Uncle John are part of this whole story, part of this whole identity. They were the ones who lived in Montana for a long, long time, and my falling in love with it was born of our many trips to see them when I was a kid. They raised four kids there, built a life there, and have been gone from it for nearly 30 years. Hard to believe. The family flag that’s still in the Montana soil was put there by me, the kid who came to it by way of Texas and then Alaska and then Arkansas and then Kentucky and then Ohio and then Alaska again and then California and then Texas and then Washington and then California again and then Montana and then Maine and then Montana again. Time, speed, distance, baby. We’re all getting there. Or somewhere. 6/10/2021 0 Comments Teaching and Beyond BurnoutOriginally published March 25, 2021

The most attention-getting thing I’ve read in the past week is this piece by Anne Helen Petersen, titled “What Demoralization Does to Teachers.” It took hold of me not just because I’m friends with a lot of teachers (I am) or because I see the factors outlined in the article playing out among those friends (I do). What stopped me cold was the distinction between burnout and what’s really happening to teachers: They’re demoralized. From the piece: What educators are feeling right now — what they’ve felt over the last year — is not just frustration and fear inspired by the pandemic. It’s not just burnout. It’s way beyond that. It’s chronic burnout and deep demoralization as their labor is increasingly under-funded, under-valued, and under-resourced. Wait, there’s more. In an article cited by Petersen, which you can read here, Doris A. Santoro writes: One reason people are not attracted to teaching, and why some are leaving teaching, is that they do not see it as a place where they can enact their values. I daresay demoralization is a destructive force whatever your line of work. What makes it so alarming in the teaching realm, of course, is that education is the bedrock for everything that follows. If we’re torching teachers—not just working them hard but also causing that work to have no meaning to them—who pays on the back end? The answer is obvious. If you think we have a problem with chronic ignorance now (and, yeah, I think we do), what happens when we’re chasing teachers out of the profession and, consequently, are unable to attract the sort of folks who have historically flocked to it? I don’t have to look far to see the worrying signs. I have a dear friend who is leaving teaching at the end of this school year. She’s not ready for retirement; indeed, she’ll have to continue working to pay the bills, retain health insurance, put gas in the car, etc. But she’s done teaching, after a long, distinguished career of doing it, after a long time of feeling called to it. But she can no longer take the misplaced priorities, the undercutting, the under-funding, the many obstacles that are lined up to stand between her and what she knows will get results in the classroom. She’s done, and it’s her community’s loss. Our community’s loss. And I suppose that would mean so much more if our community even understood what’s happening to her and, by extension, to all of us. Several years ago, I taught a semester-long honors fiction-writing course at Montana State University Billings. It was harder than I ever imagined it would be, and I have a pretty vivid imagination for such things. But I threw myself into it, and indemnified as I was against the more tedious aspects of being an instructor there—I was a visiting writer, so I didn’t have committee assignments or faculty meetings or anything else of that nature—I tried my best to make connections with the self-starting students who’d chosen the course, to impart what I’ve learned but mostly to help them find ways into expressing their art. At the end of the semester, I gave a public lecture, and I chose public education as my topic, focused through the lens of my uneven relationship with it. As part of that, I asked my teacher friends to tell me what they wished their communities knew about their jobs. Some of those responses: How deeply I loved each and every student that came into my classroom. Even the ostensibly unlovable ones, I worked until I could love them, until I could see their unique and spectacular gifts. I want people to know the system is designed to use that love against you, pencil after pencil, lost planning period after lost planning period. I burned out so fast, and I wish there had been a system interested in retaining me. And ... I think people need to know how functionally illiterate most college students are … and how unsurprising it is, given how teachers at lower levels lack any sort of empowerment or incentive or respect. And ... All I want to do is teach in the way that I know is developmentally appropriate for kids. That is all my colleagues want, too. This was pre-pandemic, far enough back to be a memory and close enough to touch us. We’re in trouble, folks. We have been for a long time. The pandemic accelerated matters, but the trajectory has been disastrous for a while. Empathy for the demoralized is not hard to come by. I spent twenty-five years as a newspaper journalist, the very definition of “been there, done that.” At the end, amid quarterly staff purges, scaled-back coverage, “doing more with less” and other assorted bullshit, I walked away and into an uncertain future working life. I left not because my pay was low (it was, relative to other jobs I had the skill to do) or because it was hard work (it was ever thus). I left because the work that had been so important to me for so long didn’t seem to matter anymore, because I’d been implicitly told by the powers that be that I didn’t matter. I was a cost center, one that was aggressively being pared back. (And now, the vultures that have control of much of that line of work argue that people who do what I did for all those years aren’t journalists at all. It’s as if the business model is degradation.) And you know what? Maybe I didn’t matter at the end. If that’s so, I cut them before they could cut me. That’s a decidedly different outlook than the one I had when I entered the profession. Twenty-five years of steady erosion and declining standards beat me up pretty good. I have great affection and nothing but good wishes for those who keep answering the call at local newspapers. They are doing what I could not. Setting my own experience aside, I think it’s fair to say that when the folks develop a feeling Santoro widely ascribes to teachers—“Demoralization occurs when teachers cannot reap the moral rewards that they previously were able to access in their work”—it’s not something that can be soothed with a little time away, some breathing exercises, and some cinched-up self-care. At some point, the demoralized give up and leave, and nobody who cares the way they once did can be compelled to step in, and then what? I’ll say it again: We’re in trouble. 6/10/2021 0 Comments Some Distances Defy BridgesOriginally published March 11, 2021

My father and I were on our way to a vaccination clinic several weeks ago (1), which should have been a happy occasion, and yet tension and sharp words edged into matters, as they so often do. The clinic was close to both my house and the vet from which I’d ordered Dad’s allergy-ridden dog some food, so I laid out the plan: get our shots, drop my wife off at the house, go get his dog’s food, take him home. It should have been an unassailable itinerary but wasn’t. “Just take me home,” Dad said. “That way, you don’t have to run back and forth.” “No,” I said. “It’s a loop. And if I take you home, I’ve still gotta come back home, and you don’t get your dog food.” “I don’t need it today.” “But we’re almost there.” “OK, OK, Jesus.” And this, of course, is when my anger burned and, because I am not smart enough to hold my tongue, I let him have it: “You know, I actually have a brain, and I can actually use that brain to figure shit out.” Boom. Silence, the rest of the time we were together (2). I don’t want to hang too much on this one flare-up, except that it’s representative of almost every flare-up that ever preceded it and predictive of every conflagration yet to come. We’re two stubborn men who share a last name—but no blood (3)—and almost nothing else, except some deep-seated compulsion to love each other despite it all and to keep trying to hold together a relationship. I suppose, by that metric, we’ve done reasonably well. We’re fifty-one years in, and neither of us has cut the other loose. We’ve flirted with short-circuiting the thing a time or two, but we’ve never had a rupture we couldn’t eventually pick our way across. I’ve had the better part of my lifetime and his (4) to consider what the fundamental difference between us is, and while the flippant answer--everything—remains ever at the ready, I think the heart of it comes down to one basic thing. Reflection. That is, the essential quality of looking within to discover why you are the way you are, what experiences shaped you, how those experiences were viewed at the time and are viewed in hindsight, how they might inform the choices at the junctures yet unseen. Reflection is the currency by which I get through the world. A lot of what comes up into my face doesn’t make a lot of sense to me in the moment, particularly if I’m trying to suss out someone else’s angles or motivations. I’ve learned to trust hindsight and time to bring clarity to at least some of what initially seems inscrutable. Where I’m able, and when I sense that I won’t do more damage, I’m a big believer in closure, even if the loop that gets tied off rests solely within my own head. My momma taught me two things that have been invaluable to the flawed man I’ve grown into: I can say I’m wrong when it’s so, and I can say I’m sorry and mean it. My father has never shown me either of those two capabilities, and if he’s inclined toward reflection, he keeps those thoughts awfully close. They never travel from his head to his mouth, and thus they are at least twice removed from the ears of someone who could stand to hear them, someone who might reconsider much if he could get some help in understanding just a little. Here’s where our key difference, the factor at the root of every occasion when we get at loggerheads, tangles me up: Am I exercising a form of privilege when I put such value on reflection? My life is not like his. Nobody hassles me if I take the time to linger in my interior life (in fact, I could well argue that it’s a professional imperative). Dad’s growing up was fraught and dangerous, and it’s entirely possible that he doesn’t look behind him because so there’s so little back there he would want to see again. When I’m at my most frustrated with him, when he’s been withering in his criticism or his disdain, my wife often steps in to remind me: His whole life has been about survival. He doesn’t think about how the moments connect. He thinks about living to the next one, then the next one, then the next one. You can see it in his pantry, stocked to survive a nuclear winter, even though he eats like a bird these days. He keeps the wanting at bay. Do I have an obligation, then, to take him as I find him, to give him a pass for all that he is and all that he might well be incapable of being, and to do the heavy lifting required to meet him where he stands? Maybe. Then again, I could make a good case that I already do, and that whatever distances remain will be closed only by an equal effort from him. I’m his ride to where he needs to go. I’m his paperwork processor, the one who makes phone calls on his behalf, the reader of fine print, the sentry against scammers, the negotiator of byzantine governments and health care providers. I’m not a martyr to these things; they’re just duties I’ve picked up along the way, as first he aged and then he became elderly, as eyesight and health slowly fail him without robbing him, yet, of time altogether. I have one goal for him—a singular hope—and that’s to see him into the cosmos without pain or terror. And the scariest part of that duty is the possibility that my own health might falter before I can get him there. So we go on, he and I, to the next obligation, the next game of backgammon, the next time I’m utterly unable to explain to him who I am, what I value, where my aspirations lie, what I’ve learned along the way, and where I keep failing. Until the next time we bark at each other, then sift out the silence, then pick it up and try again. By the time you read this, our second shots will have been administered. He’s no doubt forgotten the last time we butted heads. Me? I’ve turned the memory into the hope that there won’t be a next time, or that I’ll find it within me to be a better man should it come. I wouldn’t lay favorable odds on either one. Endnotes (1) And so it was that I became aware of the phenomenon known as “vaccination envy.” Three things, OK? First, I’m 1B. Second, it was my time to be in line. Third, I would trade my chronic illness—never you mind what it is, unless you’re my doctor—for a spot deeper in line. In a friggin’ heartbeat I’d make that trade. Short version: Get off my ass. Longer version: Let’s celebrate every dose. I hope yours comes soon, if it hasn’t already. (2) I’m not saying there wasn’t a benefit. (3) I was adopted at birth. (4) He’ll be 82 this summer. He had a series of heart attacks at 53 that damn near killed him. Don’t think I’m not well aware of how close I am to how young he once was. 6/10/2021 0 Comments The Pig Life, in the DarkOriginally published January 21, 2021

A preamble, then we’ll amble: I’ve had what I consider to be four careers, and they’ve lain together haphazardly, overlapping in some ways and standing free in others. I was a newspaperman before I was a novelist, then I was both of those things together, then I ditched the newspaper life while I kept writing and started freelancing, then I became a particular kind of pipeline worker (1) while writing and freelancing, then I returned to journalism, this time on the digital side, while I kept writing and freelancing and occasionally pipelining. I point all of this out not to build a résumé—there’s been quite enough of that, thank you—but instead to get at something I’ve realized about myself only in the past few years: I’m happier when I’m busy on several fronts. I’m less likely to be thrown by life’s intrusions, I feel more a part of the existence I’ve been granted, my energy level stays up, my mind remains limber. It’s good to know yourself and your peculiarities. Beats the alternative, anyway. When I left print journalism in 2013, it was entirely a function of opportunity and sloth. I was making more money writing fiction than I was building newspapers on the swing shift, and I had to work a lot more doggedly in the office for that lesser recompense. I granted myself a release and the gift of laziness. But here’s the thing: After twenty-five years’ worth of having somewhere to be five nights a week, I quickly grew bored with all of my wonderful freedom. That’s when I became a pipeliner. And that’s where we’re going today: into the finer details of a job that gets done while its doer hides in plain sight. As the pipeline flows, it’s a shade over 330 miles from a certain launch station in east-central Missouri to a certain receive valve in northeastern Oklahoma (2). That’s line flow. If you’re a pig tracker—and I was, and I am—you’re confined to surface roads, so the distance is considerably longer. My first multi-day tracking job, back in 2015, covered this distance at the robust rate of three miles per hour. You can do the math, right? That’s 110 hours from the time the pig—the pipeline tool—is put into the system and sent downstream until it is received on the other end. Further math brings that 110 hours to four and a half days. After a pig is launched, there must be twenty-four-hour coverage of its underground movements until it arrives at the receive valve. This is where the pig tracker comes in. This person drives to pre-determined places where the pipeline crosses the surface roads and, using an array of sensory tools, takes the measure of the pig’s progress—how fast it’s traveling, how long it took to cover the distance from the previous checkpoint to the current one, when it should arrive at the next crossing, and so on. On the crew I was on, we worked in two shifts, day (noon to midnight) and night (midnight to noon). I worked nights that week. The experience struck me as an inversion of reality, casting me almost into a dreamlike state for the entirety of the week, rather like the one Alaska visitors sometimes experience when they travel there during the summer solstice (3). If not for an intricate series of alarms on my smartphone, I would have lost all sense of time (4). More than once, I lost touch with the day I was in, snoozing (or trying to) in the daylight hours and being active while the world around me slept. I explored frontiers of exhaustion I’ve not yet revisited, even as I’ve done dozens of jobs since. I also tumbled irretrievably into love not just with the work—which isn’t terribly strenuous and is done easily enough if you can run a basic suite of software—but also with the intrinsic perks of it. My friend and best man Jim Thomsen found his way into both fiction writing and freelancing at about the same time I did and, like me, made the transition after a long career in print journalism. We’ve had a lot to bond over during these years of our friendship, and of the many things he’s said that I agree with, this one stands out for its perspicacity: Writers have overdeveloped interior lives. Guilty. And let me tell you, pig tracking is an orgy of indulgence for someone who lives largely within the confines of his own thoughts. First, there’s the silent solitude. It doesn’t begin and end. It begins, it endures, then it’s interrupted by a passage of the pig, then it’s engaged again, then it endures some more, then it’s interrupted again. And so on. On my first full night of this particular job, my partner and I had thirty passes, covering our twelve hours on shift, as we went leapfrogging down the line. That’s a lot of sitting around and waiting for the pig to pass by. That’s a whole lot of exploring your own notions about a whole lot of things. Second, there’s the way the hours flow one into the next. “Night shift” is a bit of a misnomer, because by the time you join the line at midnight, night is already well along and cruising hard toward daybreak. When you’re alert—senses attenuated, your eyes adjusted to the darkness, your skin a prickle—at a time when most everything else slumbers, you notice a lot of things you might otherwise miss. How much noise you make just walking around in the dark (5). The rhythm of your own breathing. The spin of the earth, as the moon moves around you and then cedes to the sun. The migrations of nocturnal animals. The fullness of the sunrise, both the actual unveiling and those final minutes of darkness that trickle into it. How the hours beyond the dawn feel a little like they did after senior prom, when you’d stayed up for hours and emerged fuzzy-headed into the light. The only difference is that you’re wearing a yellow safety vest instead of a cummerbund. I found a lot of latitude to go deep on the things that sat in my head. That time alone was a great gift, an opportunity to noodle out some story I was working on, to reconsider some past encounter, to perhaps even reach out in the wee hours and offer amends to someone with whom I was at loggerheads. My wife, then my girlfriend, and I were a year out from our wedding when that job occurred, living across the country from each other and working steadily toward merging our lives. I had a lot of time to envision the shape of the days that were coming our way. Some people go deep into the backcountry to do their thinking. I’ve managed to find my solitude along fencelines in Missouri and Kansas and Oklahoma (6). The worst part is the first couple of hours after a night shift ends. The principle of reporting to or disengaging from that kind of work goes something like this: Save the long drives for the daytime. So if your shift ends at noon, you have to calculate where the pig is going to be twelve hours on and go find a hotel room close to that spot, so you can quickly get back to it. It’s both art and science, anticipation merged with the variables of time, speed, and distance. On that job, I slept in Marshall, Missouri, and Harrisonville, Missouri, and Iola, Kansas, and Bartlesville, Oklahoma. Every one of them was a long drive, fifty-plus miles, from where my shift ended. The sun is up, the day is in full, and you’re driving into it while trying to fight off exhaustion. You get headachy. You get to your hotel and maybe they’re not ready for you, because, you know, check-in is at 3 p.m., and that’s far too late—by then, you’ll want to be deep into the REMs. So you beg and you plead, and if you’re lucky, they’ll finally give you a room. You shower, then you eat wherever you can, because you really ought to eat something, and you do not want to turn on that TV, believe me, because you’ll never get all the way down into the best sleep if you do that. And sometimes you flip it on anyway and the news of the day gets the attention you should be giving to your pillow. The most tired I’ve ever been, in the confines of a single day, happened about fifteen years ago, on a trip with my first wife before she became my first wife. We drove from Billings to Yellowstone National Park and all through it, then came on home. Fourteen hours, and I did all the driving, except the last thirty miles, when I told her, in all seriousness, that I could see dinosaurs running alongside the road. She rightly asked me to pull over so she could take the wheel. I never saw dinosaurs on a pigging job, nor did I ever see bedsprings in the trees (7). The weariness swallows you in a different way out there. After the Yellowstone trip, I slept for one night and was subsequently fine. During a five-day pigging trip while on the night shift (8), your compromised sleep rolls over from one day to the next, and each round, you’re just a little more punchy. It’s a weird duality, though, because the sluggishness exists outside the job—I didn’t have the bandwidth for answering personal emails or undertaking complicated phone conversations, but in the narrow scope of tracking the pig, keeping the records, staying on top of where it was and where it would be, I felt ever sharp. It’s a strange thing to live in immediate clarity but to feel the mushiness and see the slow-motion unfolding of everything else just beyond your frame of vision. And here’s a kick: I love the night shift. I vastly prefer it to the more normal cycle of the day shift. The dreamlike state beckons me, I think, because I come by it honestly. Away from the pipeline, I’d have to indulge in alcohol or some other powerful drug to feel the same sensation, and I’m not indulgent in those ways. Time and motion and the absence of light achieve the same state at a much lesser cost. A new novel came out this year, my first solo effort since 2017. It’s titled And It Will Be a Beautiful Life, and at its center is a man named Max Wendt. He’s a pig tracker. It was probably inevitable that this sliver of my working life, something I initially undertook to fend off boredom, would find its way into fiction, but you’ll just have to trust me that I didn’t become a pig tracker so I could write about a pig tracker (9). The great Larry Watson, interviewed in Montana Quarterly several issues back, said something that sent me into a fit of fervent nodding. “I write from memory, not observation,” he said. “Yet my memories are formed by observations, and then memory and imagination distort those observations into something useful for fiction and something that’s also truthful in its own way.” Mr. Watson’s words are an eloquent cousin of a cruder equation I’ve often sketched out: memory + experience + imagination = fiction. The memories and experiences (and distorted observations, as Mr. Watson points out) of being a pig tracker inform the character of Max Wendt. But my life on the pipeline is not his. More important, his life off the pipeline is not mine. One of the great and worthwhile struggles of this existence is figuring out how to balance who we are and what we do and finding a way to stow the overlap. It’s hard to be good at what you do if it’s not also, at least to some extent, what you are. And yet, it’s so easy to lose yourself inside what you do to the point that you lose touch with who you are. That, I think, is the central struggle of Max Wendt. He’s a pig tracker. It’s what he does and how he sees himself, and much to his consternation, it turns out to be not nearly enough. I am not him, and he is not me, but I get it, man. I do. Endnotes (1) — Pig tracker. It doesn’t dazzle on a business card, which is OK, because not many pig trackers have business cards. (2) — I don’t talk about the companies for which I do work, for obvious reasons. I will say, though, that the job of a pig tracker exists on the safety end of things, and even if you’re anti-pipeline, you ought to be glad someone is doing that work. The pipelines are out there. Do a Google image search for “U.S. pipeline map” and behold the tangle. (3) — People mow their lawns at midnight. It’s wild. (4) — The alarms are to ensure ongoing communication with the pipeline control system. You lose track of time out there. An alarm reminds you to call in and let the engineers know where you are. (5) — And yet, there’s no fear. At least, I’ve never experienced it. I’ve been careful not to wake up folks in nearby farmhouses, and I’ve certainly been startled (a dog running loose, raccoon hunters tramping out of the woods, even a bear crashing through the brush), but I am not afraid of walking into the dark. (6) — And Michigan and Ohio and New York and Illinois and Indiana and Minnesota and Wisconsin and North Dakota. I’ve been everywhere, man. (7) — A musher I knew in Alaska, Tim Osmar, talked about seeing mattresses in the trees toward the end of the Iditarod one year. He needed some sleep. (8) — The day shift, on the other hand, is a cinch. Easy to bag eight hours of sleep. Easy to take your breakfast at the usual time. Boring, if you ask me. (9) — Who else are you going to believe? I’m the only one who knows. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed