|

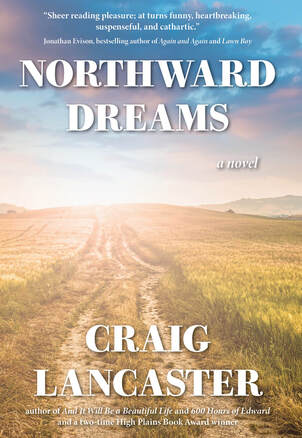

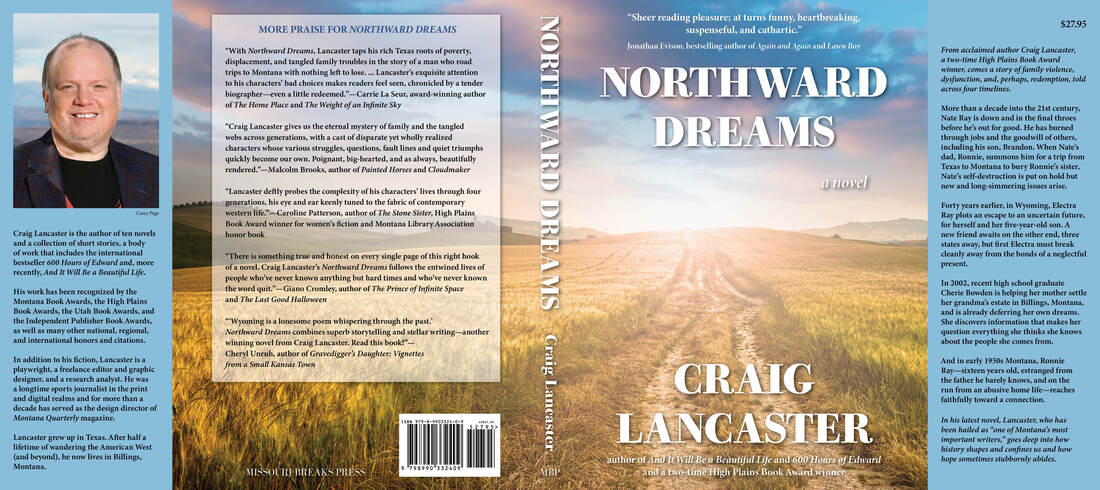

7/13/2024 0 Comments The Vicissitudes of Life**--I used this phrase in my most recent newsletter, and one of my dearest friends wrote me a wonderful email with it as the subject line. Consider this a case of virtuous recycling. It has been nearly two months since I put something new up here. Sorry/not sorry, as the saying goes. So much has happened, and I have so little to say about it, and that's a strange combination. Confronted by this dynamic in the past, I've found it best to turtle up and wait until something worthwhile comes to mind. If you're seeking mindless blather, surely there's a high-frequency, low-content Substack site out there for you. And yet, enough has changed, and enough good intentions have been met with poor follow-through, that an accounting is in order. Let's do this scattershot style: I've moved. But that's not all. Elisa covered this beautifully in her own newsletter, so I'll neither say a lot more nor take issue with any of it. She now lives in New England, her other heart earth, and I still live in Montana, mine. I'm renting space in a lovely old rambling house in my favorite Billings neighborhood, pushing on with life and art. I have a beautiful office setup that is a joy to pile into each morning. My primary work, which I find interesting and fulfilling, continues apace (you can read a piece I wrote for PaymentsJournal here). Fretless and I take walks, sometimes alone, sometimes with my roommate and her dog. I tend to my dad. I have lunch with friends. It's a good life but also a different life, and I think Elisa would say the same thing. Fiction: At a standstill Once I decided to spring Northward Dreams loose from its intended publisher, spring became a blur as I pushed out a retitled, re-jacketed version of the book and embarked on an ambitious series of appearances. Those have largely subsided as summer has come on, and it will probably be fall before I rev up again. The paperback comes out in November, and that's a good opportunity to hit the road again. I had so much fun with the hardcover. What hasn't been fun—and I'm only being honest here—is going through the wringer of publishing, which can be a heartbreaking business. Writing is the best kind of joy—challenging, yes, but also a test of self, of the quality of ideas, of endurance. Publishing...Well, if I can't say something nice, and I can't, best not to say anything at all. It's not like my travails register as important in the larger scheme of things; hell, they're not even all that interesting to me given all the ways the world is on fire (literally). But if I'm going to write stories—and I am—I will have to resolve my attitude one way or another. Right now, I feel three impulses: 1. Forget publishing altogether. 2. Find another partner like the one I just dispatched, something I never wanted to do, and approach the altar again. 3. Do with every subsequent book exactly what I did with this one. Until my heart settles, I'll do nothing. Playwriting: Stay tuned After the final curtain closed on Straight On To Stardust last fall, I set about writing a new play and turned it around quickly. It's called The Garish Sun--know your Shakespeare—and I hope to have some interesting news to pass along soon. #deliberatetease At this juncture, I'm much more interested in and satisfied by working as a dramatist than I am in writing another novel. These feelings, of course, are subject to change (and always do), so I wouldn't read anything into that declaration. Just something I wouldn't have predicted, say, three years ago. Life, man. Let's have a conversation At the beginning of July, I joined at the speaker roster at Humanities Montana. I'm thrilled about this, as a longtime admirer of and sometimes participant with this organization that advances the humanities in Montana's public life. My program, titled Where Memory and Imagination Meet, draws on subjects that have long held fascination for me—the roles of memory as an ignition point and imagination as the building blocks of fiction—but expands the idea to take in such diverse topics as family, background, community, even citizenship. When we talk about our memories of the things that shaped us and marry those with imagining different ways of talking and connecting, great things can happen. My program, like all the others sponsored by Humanities Montana, is available to schools, libraries, civic groups, and other such gatherings. Information at the link above. If you have a group in Montana that would benefit from this conversation, let's talk! Yeah, but what about all the other stuff? Oh, you mean Craig Reads the Classics? The Saturday craft talks? General keeping in touch?

What can I say? I've been quiet lately. But I'll be back. That's a promise.

0 Comments

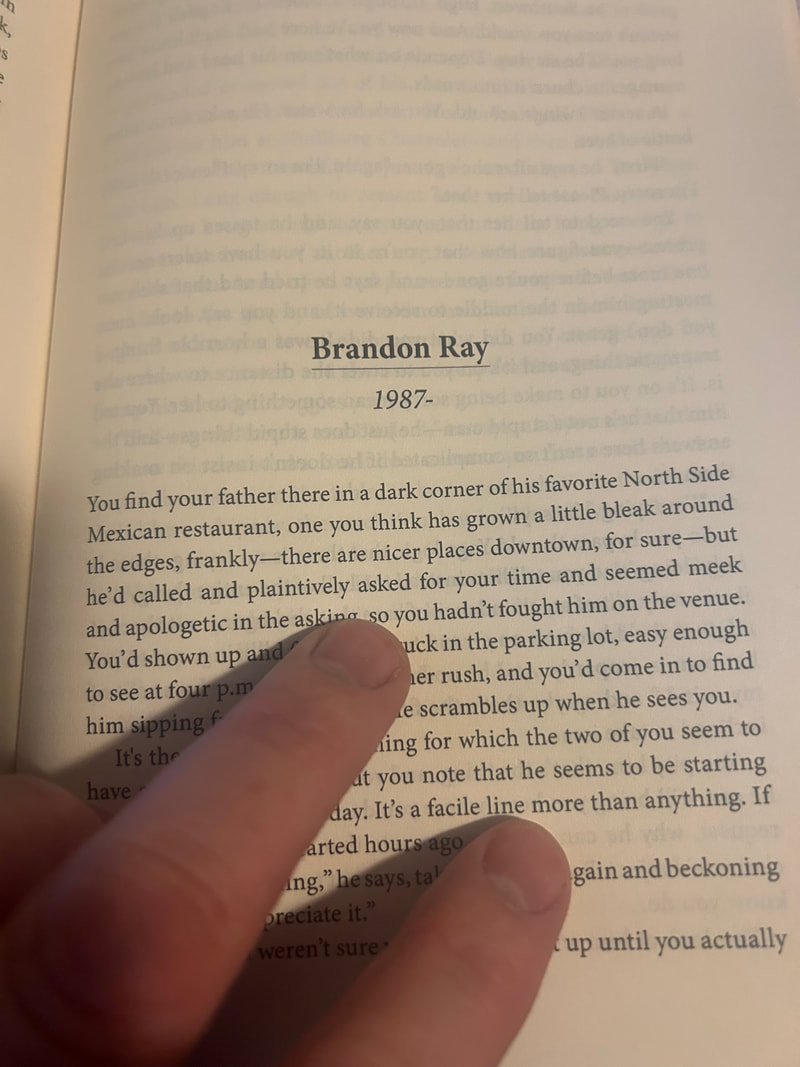

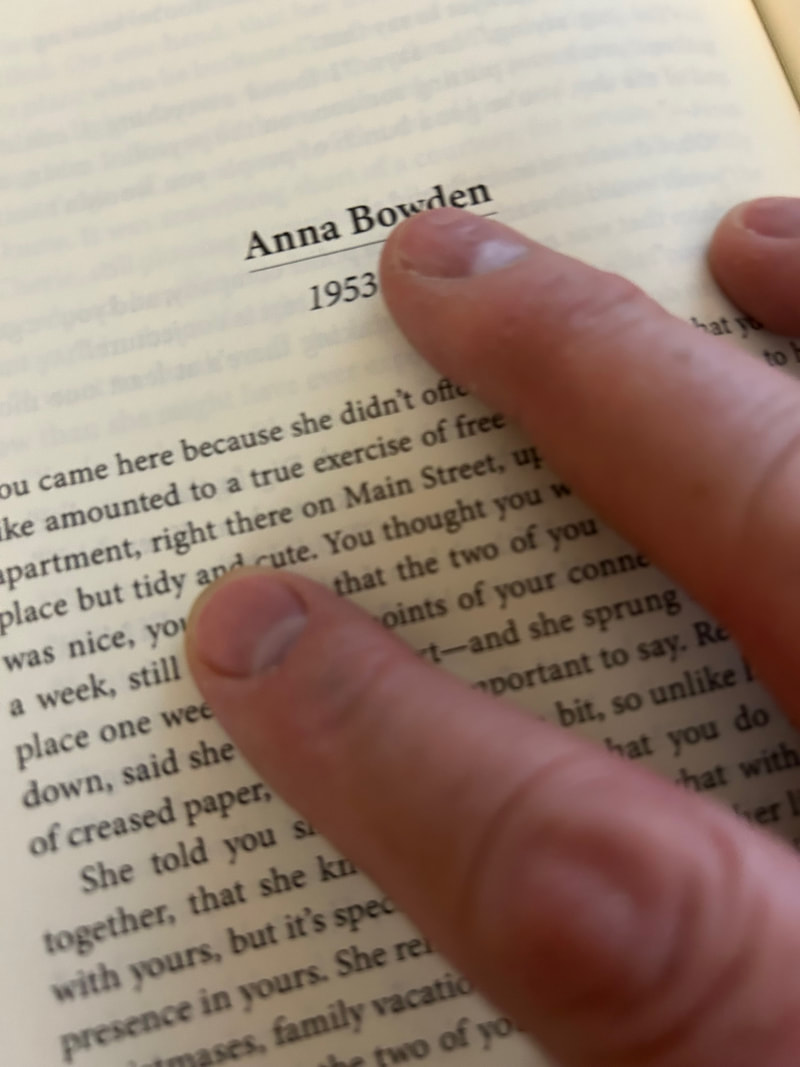

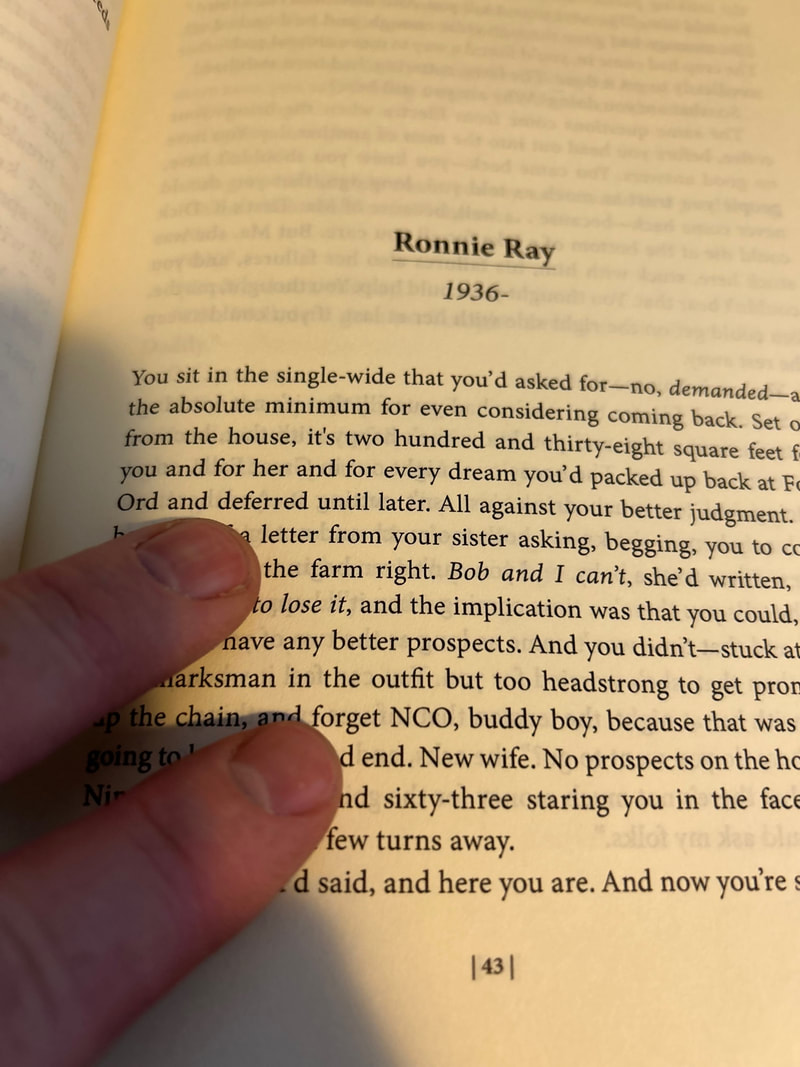

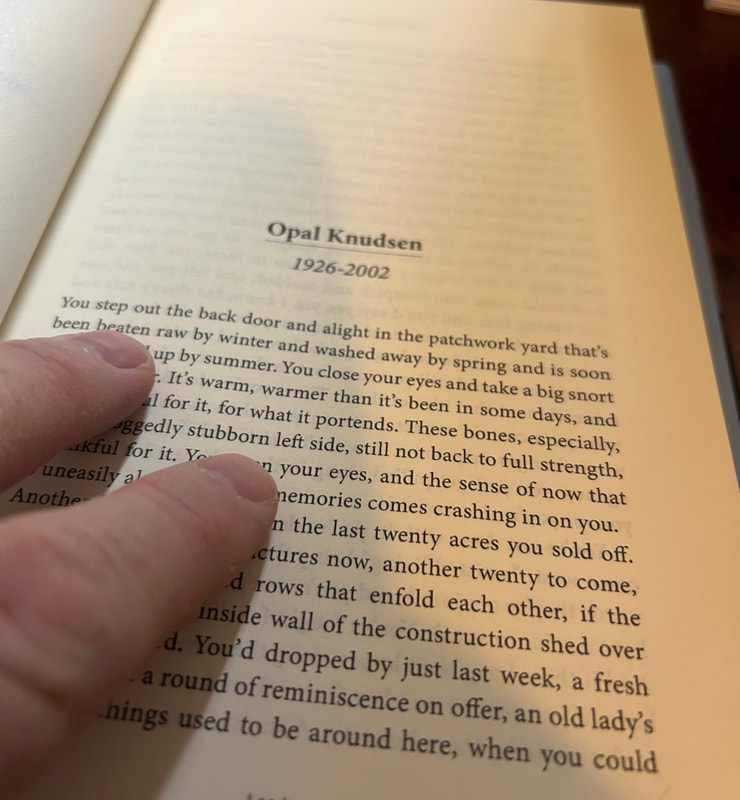

Of these nine timeline-busting chapters—just one to go after today—this one is the anomaly. It features a character who never appears on camera, as it were. Brandon Ray, son of Nathan, grandson of Ronnie, interacts with his father in phone calls that are clipped, distant, and loaded up with tension. And yet, he's essential, in that the book traffics heavily in fathers and sons and what gets passed on and where the fault lines lie. Brandon and his father are mirrors and opposites, a dynamic that also follows daughter (Cherie) and mother (Anna) in another timeline. Brandon was largely raised by another man—quite successfully, Nathan knows, and that's a source of pride and an unwanted memory, given his own path. And there's something between them—something bigger and more immediate than their shared past—and in this chapter Brandon lays out the choice the older man has in the matter. It's in the book. (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) PreviouslyOne of the interesting things about human development—to me, at least—is the occasional alignment with physics in the equal-and-opposite-reaction sense. Cherie, the centering character of the 2002 timeline in Northward Dreams, is uncommonly wise and strong for her age. Her mother, Anna, provides some of the underpinning for these qualities through her frailty and failures. Together, they make for a compelling pair. There's love and genetic bonding and deep care and frustration and exasperation. Cherie exists because Anna created her. Cherie is who she is, in part, because she must compensate for her mother. That's a hard road. Anna's inserted chapter arrives fairly late in the entire span of the book. She has made a fateful decision, the kind we don't get to walk back once it's in place. There's not a whole lot more to say without saying too much. You should read the book. (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) PreviouslyAh, Cherie. The youngest member of our ensemble, perhaps the wisest, certainly the one whose searching heart sets in motion the denouement of a book and, perhaps, beyond the page, the resetting of a troubled family. I so enjoyed writing this character, the only one central to the book who was also conjured from whole cloth. When the timelines at last converge, just beyond the pages of this inserted chapter, it's Cherie who brings them together. Cherie comes a long way in the 316 pages of this novel. When we meet her, in her 2002 timeline, she is a recent high school graduate with the onerous task of helping her emotionally feeble mother, Anna, settle her grandmother's estate. Cherie, just 18, has already experienced how the vicissitudes of life can undermine the best-laid plans. She's tired. She's also indomitable. By the time her inserted chapter rolls around, she's 10 years older, a bit more beaten down, carrying even bigger losses than before. She's ready for a change. She gets that, and so much more. (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) PreviouslyNow we come to a man in Northward Dreams who's misunderstood, misjudged, and taken too lightly. He's also a ghost and a whisper in time. He's the father sixteen-year-old Ronnie, in the 1952 timeline, reaches faithfully toward. He ends up being the car bumper in the dog's teeth. You've got him. What are you going to do now? When Oscar's timeline-breaking chapter comes in, roughly halfway through the book, it's the dawn of the 1970s, and he's far afield of where we discover him in the main narrative, working his handyman schemes. In an episode of Rich Ehisen's Open Mic podcast, I described Oscar as walking unwittingly into the teeth of his own demise. An excerpt: That's the thing about rooking people out of what's dear to them. It doesn't always work—and when it goes wrong, it's sometimes spectacularly so—but the cops almost never get called. The shame of it all is too great. How could they be so stupid, so naive? It's what you count on—that they are, in fact, so stupid, and that when the deed goes down, one way or another, their primary concern is making sure nobody else finds out. Isn't it pretty to think so, Oscar, you fated man? Read on... (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) PreviouslySo I hear what you're saying: "Craig," you're saying, "just how much of this thing is memory and just how much is imagination? You're hinting at both, but you're not really giving me the scoop. Is Northward Dreams mostly memory or mostly imagination?" Yes. That's my answer. OK, OK, so as we dive deeper into the characters and their breakout chapters, here's where the imagination definitively comes in. Erica Stidham--Charley's eventual wife, Ronnie's former wife, Nathan/Nate's forever mom, a woman with her own power dependent on no man—is no longer with us. The woman whose life provided some inspiration for her—remember the great gift I talked about in the previous installment—is most assuredly still here. She's my mother. I ought to know. You happy now? A minor bit of craft talk: When I start writing something new, I usually know little about what is going to happen but much about who will be in the middle of it. That was mostly true for Northward Dreams, save for one character: Electra. I always knew she'd be leaving early, mostly because I deeply knew the pain her son was in, and would have to be in, and would spend the story fighting against. And sure enough, when the structure of the story began taking shape, we eventually got to Electra, and her busting loose from the established timelines had to happen in a way that fortified the loss of a little boy who grew to be a good, flawed, troubled man: It's one of the cruel jokes of the universe, that he'd come to you not a year and a half ago and said, Am I going to die someday? ... You'd had to sit him down for one of the Big Talks that's in all the child development books, and you'd had to explain that, yes, he will die someday, we all die after all, but not for a long, long time. Are you and Charley going to die? Yes, but not for a long, long time. Daddy? Yes. But again... More craft talk: I mention empathy a lot. It's an essential ingredient. When a memory prompts an idea, imagination sweeps in and leaves you with characters whose defining characteristics and subtleties are yet to be discovered. Empathy—understanding them and their thoughts, choices, and motivations—is the pathway to realizing what you wish to do with the work. I found empathy with Electra, and found her to have surface-level commonalities with my mother but also to possess qualities that were uniquely hers. I didn't have to imagine my mother's death—and good, because I would have hated to contemplate that. I had to feel what losing Electra would be like—her own sense of it, yes, but also, and especially, what it would do to her child. It was a gut punch, both ways. (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy. (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) PreviouslyOnward we go into primary, secondary, and even tertiary characters from Northward Dreams who break away from the main narrative in a series of chapters that exist beyond the boundaries of the book's four established timelines. My role is not to play favorites with characters. My job, such as it is, lies in achieving empathy with all of them, listening to what they have to say, and, at least in the case of these chapters, talking to them. But if I were inclined to play favorites, Charley might well be my choice. You don't have to know a lot about me to know why. The most consequential male role model in my life is my stepfather. That my mother imagined something different for our lives and took us to him remains the single biggest gift I'll ever receive. That's well-covered ground. One could argue—I certainly would—that without that gift, this novel wouldn't have come to me. I would further surmise that the writing life itself might have been beyond my reach without that gift's presence, but that is an unknowable for which I am grateful. As I often say, though, there is memory (what actually happened, or what we perceive happened in our faulty hindsight), there is imagination (the fanciful stuff of world- and character-building), and there is what comes where the two meet. Charley Stidham won't tell you a thing about the life of the boy I was (and why should you be interested?). He'll tell you much about what it is to love, and to yearn, and to find gifts in the unexpected. As Charley's chapter dawns, he is arriving at the concluding paragraph of a life spent with words. Retirement. It's 2005, and he has seen a lot. There have been losses along the way, as there are for anyone with the audacity to live long enough to see them. He also has a whale of a surprise lurking at a public event he reluctantly attends: You're struck by something. You can still hear her when his mouth flies open, can see her inside his eyes and the small of his mouth, remember the way she would sometimes throw herself between the two of you in a fraught moment, until she learned to trust, and until you made your own way with him and all of you became a three-legged family and learned how to lope along together. And then... And then? You'll have to read the book. (Be sure to note in the comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.) PreviouslyThis is a continuation of the look at various characters from Northward Dreams and how they're presented outside the four established timelines in a series of inserted chapters. If Opal Knudsen, the subject who opens the book, is the master key to the story, Ronnie Ray is the rippling thread that runs through it: a sixteen-year-old runaway in search of connection in 1952; a man being run from twenty years later, one who feels as though something has been taken from him; and the elderly puzzlement to his troubled adult son in 2012, when at last all the timelines converge. Ronnie was fascinating to write, not least of all because I both understand him on a cellular level—the pain, the incompleteness, the inability to rise to the needs of someone else—and because I've spent a lifetime trying to connect with an older man (my father) to whom I'm tethered, to whom I give love, and whom I'd never, ever in a million years choose to know if he hadn't come to me in the bargain that comes with being granted life. How's that for a tease? Ronnie's broken-out chapter takes place in the early 1960s, roughly a decade after his boyhood reaching out and roughly a decade before he loses his wife and son to his inattention and the call of a better life. He's just out of the Army, he has undertaken something he was once warned not to do, and he's thrashing about. Excerpt: So you tell Electra that you've had your fill, that it's not working, that you want to go, and you know she's happy with that, because she wants to go, too. The occasional night out in Great Falls, some dancing and too much drink, just isn't cutting it. And here, on this lonely bench, she knows both too much and not enough. She's restless. She wants a baby, and you can't even begin to picture that, but she tells you there's a time coming when it'll happen and it'll be right, and that time won't come as long as the two of you are here. Want to know more? I hope so. (Be sure to note in comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.)

Now that Northward Dreams, at long last, is out in the world and available in hardcover and e-book (with the audiobook on the way!), I'm enjoying the payoff for all the lonely work of writing it and preparing it for delivery: the idea that there are people out there reading it. (Thank you!) If you're one of those people, you didn't have to go far—the very first words—to encounter one of the book's devices, for lack of a better word. Spread out among the 32 numbered chapters of the book, which encompass four timelines (1952, 1972, 2002, 2012), are nine chapters that focus on individual characters who inhabit the book. These chapters—which I've heretofore been misnaming as intercalaries—exist outside the story's established timelines and illuminate aspects of the characters that inform the whole of the narrative. They're also written in second person, a choice I expanded on in this interview with Chérie Newman: I think I went with the second-person point of view initially just to talk to them: Here's what's happening to you, what you're feeling, why it has gone the way it has. Any notion I had about changing that up went away once I saw the effect. There's an immediacy to the POV. Those characters are illuminated in ways they couldn't have been even in close third person. So that's why I did it, but this isn't really about that. (It's not expressly a craft talk.) Instead, I want to dig into who these characters are and why they spoke to me—and why they allowed me to speak to them—without giving away the essential plot, so to speak. (Before I get too far into that, about the errant use of intercalary: These chapters don't quite fit the accepted definition because they do involve main characters and are less about theme, I think, than they are about backstory. For a more traditional view of the intercalary, think of the turtle chapter of The Grapes of Wrath. I certainly do—I referenced it many years ago in a short story.) Opal goes first because...she goes. She dies, right there on Page 13: You kneel, the knees of your jeans in the mud, and you take the clipping shears from your apron pocket. You size up the job, and you pitch forward into the bush. Two crows, languid on the telephone line above, bear witness. Across the way, the hammering goes on, beating out a rhythm, a simple song for the dead and gone. Here's the thing about Opal, though: She is, in a significant way, the master key to the story, the connector of 1952 and 1972 and 2002, when she leaves us, and even 2012, when she's a full decade gone. Without Opal, the connections among Ronnie and Cherie and Nate and Electra—the four primary characters of those timelines—lack resonance. And without those four, Oscar and Anna and Charley and Brandon are four characters in search of a story. In subsequent installments of this series of posts, I'll introduce you to all of them. You'll just have to believe me that they all fit, eventually. Or read the book, please! (Be sure to note in comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.)

I'm going to tell this story only once, for posterity, perhaps, or maybe just because it's so bizarre that I'll want to have this record in a year or 10 years or 20, when I won't remember the fine details anymore.

Soon—very, very soon—my 10th novel will be out in the world, available in a variety of formats through just about any retailer that sells books. For the longest time—and that's part of the story, really, the loooong time—my assumption was that it would be called Dreaming Northward and would be released by the publisher behind my previous book, And It Will Be a Beautiful Life. We had a good relationship, this publisher and I, and I expected our association to go on and on, to the end of my career. But it didn't go that way. On March 11, the day before Dreaming Northward was set for a fractured release, with the e-book going out first and the hardcover and audiobook supposedly to follow at some ill-defined point, I asked the publisher to cancel the book and immediately revert all rights to me. (That request was granted, for which I am grateful.) I will not engage in a blow-by-blow description of all the ways I believe my trust and faith were compromised. And I have no desire to harm this publisher; indeed, despite it all, I have great affection for the guy running the operation and would even consider a return if certain factors that beleaguered this book were dealt with and overcome. Obviously, the publisher might not be interested in a reunion, given the events of the past week. I'm just being clear about where I am on this. I'm not mad. I'm not even hurt, not really. I'm just sad and disappointed over the outcome but also resolute that it had to happen. Dreaming Northward is gone. Northward Dreams lives.

So why did I do it? It's not like publishing contracts are easy to get. It's not like I'm a well enough known quantity that I can act like a spoiled child and get away with it (or even foment the impression that I'm a spoiled child). It's not like I have this notion that independent publishing is a dream trip. I've taken it, and it's not. It's a slog. It's exhausting. It's an endeavor undertaken with the odds ever against you.

So first, let me say this: I'm a lot of things, but I'm not a spoiled child. Second, I've been around enough publishing blocks—self-publishing, small publishing, big publishing with powerhouse marketing and backed by big-time agencies, etc.—to know that almost everything is a crapshoot for almost everybody. In this case, the promises made to me about how my book would be positioned and the marketing muscle that would be put behind it were, in retrospect, dependent on a round of funding my publisher kept promising was imminent, month after month after month. After this book slid from its original publication date in June 2023 all the way to the doorstep of last fall, I asked for a Spring 2024 date, thinking that might provide the necessary buffer for the funding to come through and for the marketing pieces to be put in play. Many, many times, I was told the funding was just a signature or a courier away from being realized. Month after month, it didn't show up. In late January, I asked if the March 12 release date was going to hold. Yes, I was told. But in the end, that cratered, too. The e-book was definitely going to come out, but the hardcover would have to be delayed. That was the eventual word. How long would the delay be? No one could say. I wasn't comfortable, but I was willing to go along and have faith. We were so close. Then came March 11 and word of another funding delay, and that ended my faith. I couldn't trust that the hardcover edition would ever come out. The more I considered it, the more I feared that the e-book would get launched, nothing else would come up behind, the whole thing would eventually crash, and I would have to pick up a barely breathing book and try to resuscitate it on the fly. It was just a bizarre episode. Not two days before I asked for a reversion, I stood in front of 50 people at the Billings Public Library, talked about And It Will Be a Beautiful Life (the most recent selection for the One Book Billings community reading program), and premiered a video about Dreaming Northward. (The video has been edited in light of recent events and can be seen below.)

I had every expectation that my book release, flawed as it might have been, would be realized. Then Monday dawned, and with it came another funding delay and my publisher's declaration that he was leaving his post for a couple of weeks amid this latest setback. He said he had to shore up his affairs in light of the situation. That was the final blow to my trust.

I asked for my book back. I made arrangements to publish it myself, through my own boutique house. In a frenzied 24-hour period, I conjured a new title, designed a new jacket, got hardcover files together and uploaded, got the e-book file to my designer, revamped this website, reworked marketing materials (such as Facebook headers and event posters), contacted booksellers and librarians who have already booked me, and, somewhere in there, bagged a few hours of sleep. Just last night, I approved the hardcover files with my printer/distributor and officially set a publication date: March 19, 2024. As I said on Facebook: I lost a week. I gained my whole book. It's not remotely what I anticipated or wanted. But it's my project now, and I'm determined to push it as far as it will go. I'll have to do some fundraising. I'll have to come up with some clever and creative marketing approaches. I'll have to look for people to say yes. Bring it on.

So the e-book comes out first. What's the big deal?

Look, I love e-books. That's how thousands and thousands of readers have been exposed to my work. But my passion lies in supporting independent bookstores, and this was always going to be a bookstore book. There were grand plans—personal letters to booksellers from my publisher and me, flashy campaigns through Bookshop.org, maybe a tour. All dependent on funding, of course. And it wasn't so much that the e-book would go first that bothered me as the fact that I no longer believed the hardcover would appear at all, given the dead promises along the way. There was no way to be OK with that. My faith was expended. That doesn't mean I wish bad things for my old publisher now that my book is out of the mix there. On the contrary, I hope I'm extraordinarily wrong about my suspicion of how that situation will finally play out. I hope he calls me in a few months and says, "You should have waited, buddy boy," and sends me videos of his lighting cigars with hundred-dollar bills. I'd be thrilled for him because he's a good man, and he was hands down the best editorial partner I've ever had. Publishing is hard work. It's even harder on a shoestring budget (as I well know and am about to experience again). I don't hold my publisher's inability to do right by this book against him. He was trying. Hard. But it wasn't happening, and in the face of that reality, my loyalty had to be to my work. In short, even if my publisher's highest ambitions come to fruition, I made the right call, given the track record. At the moment I had to make a decision, I made what I consider to be the brave one. I chose my work. I chose my sense of integrity. "If it's not hell yes, it's no" is a great clarifier in matters of choice. Sticking to that rubric, even when the answers aren't easy and even when the wish is for a different outcome, can keep one from committing reservedly to something that requires one's whole heart. I was no longer at "hell yes." Therefore, it had to be "no." |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed