|

Here's the dirty little secret of my life as a novelist: I'm terribly read, at least in the realm of fiction. When it comes to nonfiction, poetry, current events, studies about financial inclusion, etc., etc., things look better for me, but fiction is a weak spot in my repertoire. The reason is both simple and counterintuitive: I write fiction. I'm too busy doing what I do to spend as much time as I'd like on what other people do. This year, however, I've decided to dedicate a small part of each day—30 minutes, in the wee hours of the morning—to reading fiction. This means I move slowly. It also means I get to savor something—or live long with the bitter taste, depending on how I'm feeling about my selection. To focus my efforts, I've decided to read works that are generally regarded as classics. This, of course, still leaves a wide field from which to choose, and the criteria for curation are mine alone. My only rigid rule: If one month I read a work by a man, the next month I will read a work by a woman. And vice versa. I also intend to take in diverse work*, in as many forms of diversity as I can. Have a suggestion for me? Drop it here. I have every expectation that this will be a humbling exercise. I'm going to read books I should have read a long time ago, and I'm going to be accountable to myself here, which means I'll be accountable to you. I fully expect to be greeted with incredulous declarations of "you haven't read that book, you philistine?", and I rather think my layman's approach to literature—I am not, by any stretch, an academic—will expose my shortcomings in assessing what I've read. On the other hand, I will receive these books as I imagine most of their readers, historically, have received them. And to this reception I will bring some amount of knowledge about the decisions a novelist makes as he/she/they do the work. Today, I start this journey with The Razor's Edge, by W. Somerset Maugham. How I came to this one was a bit haphazard: I had gone to my local library to pick up To the Lighthouse, by Virginia Woolf, as my starter. No copy was available, so I perused the shelves, waiting to be inspired. I'd read Maugham's Of Human Bondage in high school and remembered liking it, although as god is my witness, I cannot recall why or even much about the book. Too many intervening years. So I plucked The Razor's Edge and started there, with the library loaner copy having a return date. I bought To the Lighthouse at This House of Books, so it's up next. The Razor's Edge  By W. Somerset Maugham Publisher: Vintage (2003 edition) Originally published: 1944 My review, in a nutshell: I couldn't wait for it to end I should say this in the book's favor at the outset: I found much to admire early on, particularly Maugham's style and sentences, which I think are what I also enjoyed as a callow teenager when I tackled Of Human Bondage. But in the final analysis, I found the book to be maddening and dense, and in the last 30 pages or so, rather than savoring each tender morsel, I found myself hanging in there out of pure animus and a desire to conquer it. Among the aspects I found irksome: 1. The decision to filter everything through a secondary or tertiary party—and to call that narrator "Mr. Maugham"—struck me as ineffective and bizarre. The central character—the one whose journey of self-discovery confounds the well-moneyed people who know him—is former military pilot Larry Darrell, and yet we don't experience his transformations through his eyes but rather through those who think they know him and, in small snippets, from Larry himself on those rare occasions when he drifts back into the social circles he knew as a younger man. Until we do see it through his eyes but have given up. See Point No. 2. 2. The book makes a great fuss of Larry's inscrutability and unwillingness to share much of himself ... until he drones on for hours toward the end of the book, telling Maugham (the character, not the author, but who knows?) all in hopelessly long paragraphs that unfurl endlessly, no bit of arcana to obscure to leave out. To what end? We don't really know. Larry used to not talk of himself much at all, and at the end he cannot shut up. I didn't buy it. 3. This, no doubt, is the perspective of someone born late in the 20th century and thus not applicable to the audiences that received this book in 1944, so take it as you will: I had quite my fill of snobbish society early in the book, which made the rest of it a gutful as I slogged through the (many, many) remaining chapters. Elliott Templeton, the uncle of awful Isabel, who loves Larry but never has him, is charming enough and decent enough, but I'd had enough of him long before he exited the stage. Enough, too, of Mr. Maugham (the character, not the ... oh, hell, never mind), although I'll grant you that he was a bit more accepting of human frailty and thus was easier to take. It's nice when you can write yourself—or your avatar of the same name, anyway—to best advantage, I guess. I found this to be a rare case of my vastly preferring the movie (for me, the 1984 version starring Bill Murray, although I have also seen the 1946 original starring Tyrone Power). The movies center on Larry as the main character on a baffling—to onlookers—search for meaning. The book, with Mr. Maugham (the character, not the ... well, you know) as the portal for all perspectives, mostly renders Darrell's experiences as nothing more than long soliloquies by the other characters. It's not nearly as effective. Those characters are glib and haughty and annoying, and they wear on the reader. This reader, anyway.  *—Now, about diversity ... Years ago, a friend with whom I eventually lost contact, knowing I was interested in all things Hemingway, gave me a book titled With Hemingway. In that book, written by a young North Dakotan named Arnold Samuelson, Hemingway offered a list of the books one must read to be educated, by Papa's estimation. "Some may bore you, others might inspire you, and others are so beautifully written they'll make you feel it's hopeless for you to try to write." Here's the list: The Blue Hotel and The Open Boat, by Stephen Crane Madame Bovary, by Gustave Flaubert The Red and the Black, by Stendhal Of Human Bondage, by W. Somerset Maugham Anna Karenina and War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy Buddenbrooks, by Thomas Mann Hail and Farewell, by George Moore The Brothers Karamazov, by Fyodor Dostoevsky The Oxford Book of English Verse The Enormous Room, by E.E. Cummings Wuthering Heights, by Emily Bronte Far Away and Long Ago, by W.H. Hudson The American, by Henry James It's entirely possible I'll poach a title or two from Hemingway's list—I very nearly picked up Madame Bovary for my third selection before opting for a Bradbury book—but this roster is notable for several things that don't appeal to me, notably that only one woman, a Bronte, passed muster. I think I can do better than that. Gonna try, anyway.

0 Comments

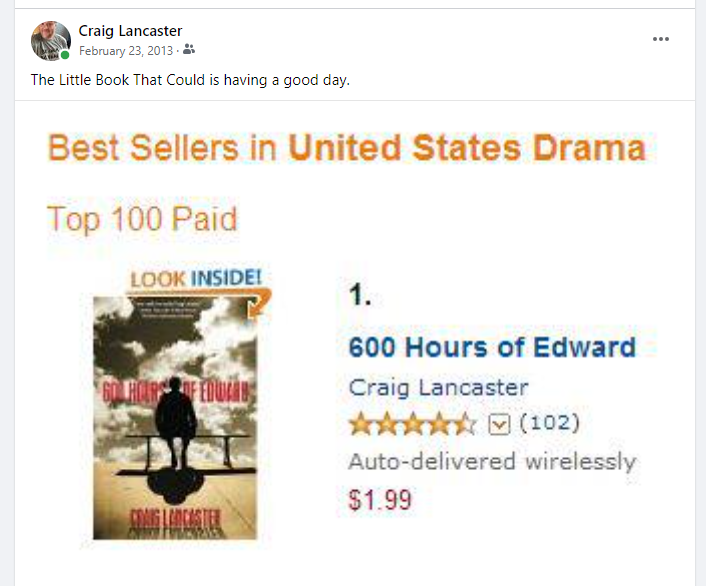

2/23/2024 0 Comments An Artifact of a Bygone EraThank goodness for Facebook memories—I guess—as I otherwise would not have seen that I posted this picture and this comment on my timeline 11 years ago: Eleven years seems like a long time ago, perhaps because it was a long time ago. And 11 years ago, I would have been loath to discuss the following topic, which I'm only too happy to discuss today: I am not, for the purposes of self-identity or self-esteem, a bestselling author or an international bestseller or an author whose works have been widely translated or a two-time High Plains Book Award winner. I am, for the purposes of advertising and marketing, all of those things. The differences between am not and am are profound, and learning to understand and appreciate those differences took me a long time and no doubt occasionally made me fairly insufferable. Live and learn. I think I can tell you exactly how my first novel, in 2013, went straight up to No. 1, if I may borrow from Bad Company. Of course, I'm biased in the analysis, so I'll tell you that writing a good book had something to do with it. I'm a realist, too, so I'll also say it had far more to do with a rising tide of readers eager to acquire e-books, a publisher with unparalleled access to those readers, and a price that encouraged those e-reader-wielding book lovers to take a chance on my novel without an onerous investment. Consequently, that book—and I—had a very, very good day (and week and month, and, really, a few good years). I'm nothing but grateful. And, sure, from a marketing perspective, I appreciate the bestseller label. It has had a far longer life than the actual bestselling ever did. We—the royal we of the publishing universe—hold fast to a bestseller status because we think it helps sell books. We festoon award stickers on hardcovers and paperbacks because we think it helps sell books. We seek out testimonials from other authors because we think it helps sell books. (And, on the flip side, we try to say yes to authors asking us to supply testimonials for their books because we really, really hope it helps sell books!) And at least to some extent, I'm certain all of that is helpful. But the degree of help is ephemeral and unmeasurable, and that's why the best an author can ultimately do is to (a) write the best book possible at the time of the undertaking and (b) work as hard as possible on its behalf once it has emerged into the world. Those are controllable factors. The rest...are not. Harder to accept, I think, is the truth that my friend Allen Morris Jones, one of my favorite authors, recently laid bare in his excellent newsletter, Storytelling for Human Beings: "There is very little rhyme to literary fame, almost no discernible reason. The breadth of your talent and the depth of your persistence are only a couple chunks of okra in that roiling, haphazard whatchagot stew of literary recognition. A few lucky souls end up making a reputation and a living. The rest of us tread water, watching our ship churn away over the horizon." That's sobering, yeah? Still, sobriety is vastly preferable to drunkenness on one's own marketing materials. I had a blast that day 11 years ago, I sold hundreds and hundreds of books, I made a fair amount of money (all of it now gone), and I didn't have to do anything stupid in the bargain. I'll continue to use the bestseller label, even if the fuller context is "author of a handful of bestselling books and a larger handful that you probably haven't read, not that he's complaining."

Luckily, the limited room on a book cover rewards brevity in these matters. 2/19/2024 2 Comments Like Planes on the RunwayI suppose this could be a Saturday Morning Craft Talk, except it's not Saturday morning* and it's not particularly crafty. So scratch that. No. No, it couldn't. It does, however, speak to an aspect of the writing life, one that varies wildly from writer to writer, if my conversations with colleagues and contemporaries are any guide. What does one do with the ideas when they're not actively being worked on? It's a good question, one with a slapdash answer for me. I'd love to be a capital-letter Artiste, with a leather-bound notebook that never leaves my side, with stacks of brimming journals, with a catalog of every thought I've ever had and a handwritten account of every beauty I've ever witnessed. Alas. I'm just a guy with a brain, such as it is. My ideas—what I've thought of doing, what I'd like to do, what I'm considering, what I've started and not finished, etc.—are all in there, in some stage of marination. It's no doubt a terribly inefficient system, but I'm not complaining. I wrote my first novel in 2008, a breakthrough that came after years of wanting to and not really knowing how. Since then, I've not lacked ideas; indeed, I often describe my notions as being backed up like planes on the runway. But an archivist, I am not. Nor an inventory specialist. Nor a tour guide. Whatever I will or might do is up here—*taps head with index finger*—and I'm the guy with the key. I'll take the key, and the ideas, with me when I go. And that will be that. I've written before about the linear way in which I work—start at the beginning, then write straight through until the end, if I can get there. (I've also written before about how that linearity is subject to the needs of revision, when I'll happily move things around, delete things altogether, or augment the bits that aren't quite cooked.) This, too, is a terribly inefficient system, in that my early days of writing fiction were marked by a sense of loss and bewilderment when a manuscript just didn't go. I'd stash whatever I'd managed to do on a hard drive somewhere, nurse my wounds, shake off the disappointment, then try again with another idea. Fortunately, a new one would be at the ready. Planes and runways and all that. Those half-baked attempts, tucked away in their little folders, were dead things I couldn't bring myself to bury, even though I knew I wouldn't resuscitate them. A few things got salvaged for other purposes--Somebody Has to Lose, at 14,000 words my longest short story, is one such reclamation. But mostly, they take up computer memory and lie dead and crumbling. This used to bother me a lot, just from the standpoint of industry: All that work for nothing. All those words expended and nothing tangible to hold. Boy, was I wrong.  For one thing—and apologies for such a hoary cliche—there's a lesson in every failure, and not every failure is what it seems. This would have come as quite the surprise to the me of 15 years ago, who upon breaking through and at last writing a novel thought he had figured everything out. I didn't know anything. If possible, I know even less today than I knew then. Or I simply know different, better things. For instance... I've learned to wait on it. The manuscript that became And It Will Be a Beautiful Life came out slowly amid several stops and starts, and over the course of a few years. I started it in Montana, pecked away at it in Maine, and found my way through, at last, upon returning to heart earth. It wasn't entirely a function of geography, though I'm convinced that had much to do with it. I simply had the patience to wait for the memories and the imagination to steep properly. That's age. That's experience. That's trust. That's love. A while back, an artist friend introduced me to a well-known author with this: "Craig is a book-a-year guy." True once, but not so much anymore. As a less experienced novelist, I wouldn't have trusted myself to wait for the right idea to emerge in its own time. I wanted, needed, to write the next book, and quickly, if only to prove to myself that I still could. Today, I have no such worries. I know I can do it. I also know the idea I should be working on will let me know when it's ready. Giving it time and space to bloom is granting myself grace in the bargain. I'm increasing the likelihood that I'll find my way through because I'm letting the thing come to me instead of stampeding it. So, about the planes and the runway...

My next novel is just a couple of weeks from being released, the idea having germinated and taken root and blossomed nicely. The one likely to be next is written and ready for the publishing gamut, and that took me the better part of a decade, start to finish. After that? Planes on the runway, baby. I have three manuscripts in various stages of development. I suspect, but don't know, that all will find their way to the finish line. (Big disclaimer: If I have enough time. I've reached a time of life when I worry less about the ideas and more about whether I'll be around to snag all of them.) I'm enchanted with all three stories, but it's not time to finish any of them yet. Soon. Eventually. I trust the process, if not the clock. At long last, I trust the process. *--It's Monday afternoon. Thanks for the long weekend, presidents. 1/7/2024 3 Comments Sunday Morning Craft Talk*

*—if you'll indulge me.

Let's talk about sentimentality. The hook for this is simple enough; just yesterday, I posted something old/new at The Short Story Project: a 2011 story of mine called Comfort and Joy, which appears in my collection The Art of Departure. In the blurb that accompanies the post, I described the story as "unabashedly sentimental," which it is, then I proceeded to be bothered by that description for the next few hours, until I sat down to write this.

Why was I bothered? Perhaps because sentimentality is not highly regarded as a quality of serious fiction. While I'm fairly solid in my commitment to not caring terribly much what someone thinks of me personally—within limits, of course, my being human and all—I do get a bit crinkled when my work isn't taken seriously. See again: being human and all. Let me be clear here: I'm not holding out Comfort and Joy as some superior work of art. It's not. I haven't read it in years, but I know where it fell in the course of my fiction-writing career (early), and I'm certain that if I looked at it again, I would see much I wanted to do differently were I given another shot at it. But for better and worse—tilted heavily toward better—there are precious few do-overs in publishing. Mostly, you do it and live with it. I can live with Comfort and Joy. Its primary strength is this, more than a decade after it was written: It is precisely what I wanted it to be. I am taken with Capra-esque cinema, and I set out to write a Christmas story that captured a similar feel: an isolated old man with a compelling but obscure backstory, a little boy burdened by loss, a mother at loose ends, and the unlikelihood of their forging connections with each other. Happy ending? God, yes. Essential. Like George Bailey being rescued by the people whose lives he made better. Like Clarence getting his wings. Comfort and Joy hit every note I wished to play. Can you occasionally hear my fingers on the strings? Quite probably. But that's a limitation of the craftsman, not a failure of the story. One of my all-time favorite quotes is this one from Roger Ebert: "It's not what a movie is about, it's how it is about it." So it is with any artistic endeavor, I believe. Did you, the artist, do what you set out to do with the work? Yes? Congratulations! You've found success. What other people think you ought to have done is beside the point. Let them write their own stories if they feel so strongly about it.

My intent here is not to launch a spirited defense of my own work but to pose an essential question: If art is about the human condition—its variables, its beauty, its ugliness, and all the imaginable in-betweens—how can sentimentality be relegated to the outside of that? I'm not talking about the glorification of treacle or granting myself free rein to load up stories with so much sugar that readers' teeth fall out. I'm talking about acknowledging a human yearning for sentiment, a human response to what is stirred up in its wake, the emotional outlet it supplies. To my mind, it's rather like humor, another quality often underplayed and undervalued in so-called serious literature. Zaniness may not carry the heft and complexity of irony, but it damn sure offers a compelling reflection of humanity as I know it and aspects of human beings as I know them.

Finally, let's talk about happy endings.

There's little upside to being scholarly about my own work—let me acknowledge that before I say this next bit—but if my stories demonstrate anything, it's that the narrative and the pages eventually end but the story never really does. Think of Edward Stanton looking across the street or Mitch Quillen driving home to his kids, or, more recently, Max Wendt waiting to find out where the flow will take him next. There's so much story beyond the page, and my particular way of writing often compels me to put the responsibility in readers' hands when my words are expended: It goes somewhere from here. Where do you imagine that is? I love doing the same with the stories I'm told. George, the richest man in town, isn't going to jail or being run out of town on a rail. Is Potter? Will Nick someday move along and open a more rollicking joint for men who want to get drunk fast? Do George's kids eventually get out of Bedford Falls, the way he wished to, and will he encourage them in the way his own sainted father encouraged him? It's up to me. What a great privilege.

So, in my unabashedly sentimental short story, the ending comes as the old man stares out of a broken window and beholds unfettered joy. But the lives inhabiting the story, presumably, go on, into other days and moments, into other happinesses and heartbreaks, into gains and losses and despair and redemption. Experience enough of those things and you just might become sentimental about them.

11/4/2023 0 Comments Saturday Morning Craft Talk......if you'll indulge me. Tonight, Yellowstone Repertory Theatre wraps up its nine-performance run of Straight On To Stardust, my first full-length play. To say it's been a privilege would be a damnable understatement. To say it's been fun would be to undersell the word. To say I'm going to miss it... Well. Yeah, I will. I hope this isn't the end, but if it is, I couldn't have enjoyed nine days and nights any more than I have, and I certainly couldn't have seen my play taken on a maiden voyage by any group more loving and talented than the YRT ensemble and its intrepid leader, Craig Huisenga. I'm a writer, so I'm not terribly unusual in that I want nothing more than to undertake the next writing project. Another play, perhaps. Maybe a novel. A short story. I don't know. The idea will tap me on the shoulder soon enough, and I'll be in my seat, doing what I do. In the meantime, I'd like to see where else Stardust might alight. Have some ideas? Talk to me. Want to download the media kit and read an excerpt, see some photos, read some reviews? Have at it. But about that craft talk... Occasionally, I'll read a book review, or even the book itself, and the reviewer and/or I will be awed by the incredible sweep of a story, how it captures an era or a movement or a moment in our lives, and I'll have that inevitable feeling of being unworthy: How, I'll wonder, can I call myself a writer of fiction when I lack the imagination to conjure a story that so richly conveys detail and so expertly takes in such abundant themes? This is doubt, by the way, standing on the shoulder and whispering poison into the ear. The problem: Those in the throes of such doubt often lack the ability to stand back and gain perspective in the moments when they most need it. So we ask ourselves why we should bother when someone else, or many someones else, do it so well. In my calmer, less doubt-ridden moments, I'm able to center myself in this truth: I am not, as yet, a writer of sweep. I am a writer of the interior, in ceaseless exploration of fear and sloth and errant motivation and mistrust and love and betrayal and every possible in-between that makes us maddeningly human. I write from the inside out to better understand not just others but myself. Maybe, ultimately, especially myself. On that subject, I am taking a lifelong postgraduate course from which there is no bestowing of a diploma. There is only the next lesson. I've been thinking of these things a lot in these past few weeks of repeatedly watching Straight On To Stardust play out in front of me. This is a story of family fractures and of interior lives that are explosive in combination: a son who misses his mother and stretches out, flailing, for his father; a daughter who searches for a way in with her inscrutable dad; an ex-wife who still loves the man who denies her intimacy; a friendship held, frozen, in time and the cosmos.

When you reside in the interior and work from there, you discover, eventually, that most of the scary things behind the door you keep trying to bust down have their roots in childhood. Anybody who's been in therapy knows this; it's why counselors start there as they help their patients tunnel into the now. Generational trauma flows from child to child, often through the clearinghouse of adulthood. When we don't handle our shit, we roll it downhill to the next person. Someone, eventually, tries to pay the overdue bill. It's a hell of an inefficient way of living, with incalculable damage inflicted in the main and on the margins, but here we are. Again and again and again. It doesn't take much imagination to consider how these interior damages have great reach beyond our own lives. How might the life of one particularly public narcissist have gone differently had he been hugged more often by his father or been told that he was loved? Or let me take this to an intensely personal place: Why did I equate love with eventual abandonment throughout my 20s and 30s and 40s? (It's rhetorical, this question. I know the answer. I know it now. I learned it the hard, necessary way in my mid-40s.) It's a hell of a thing, this trauma. It's given to us, in most cases. No instructions, no way of opting out, here it is, and it's ours to carry. It often happens when we're young, but there comes a time when that's no longer an acceptable excuse for our clinging to it. Yeah, we were just kids, and yeah, it should have gone another way, but it didn't, and now the onus is on us to not inflict it on someone else. You up for that, the responsibility of that? Some of the most wrenching, yet illuminating, stretches of my life have come while I strained to get to yes when faced with that question. It's why I write. To hold these things up to the light. To understand them. Sweep? I'm not thinking about sweep. I'm thinking about getting through this life. How do I do that? How do the characters I'm living with do that? Can I listen closely enough, feel acutely enough, be compassionate enough on their journey? Can they find their way through? Can I help as I walk with them? I want to. I need to. 10/12/2023 4 Comments Closing the Loop: On EndingsThis, I suppose, could fall into the category of a Saturday Afternoon Craft Talk, except it's Thursday afternoon and I don't much feel like being bound by time. We're coming up hard on the first of November, and that will mark 15 years since I began writing my first novel, 600 Hours of Edward. The backstory of how that book came to be is oft-told, no repeats necessary. I will say simply that it was not only my first novel but also the first book-length manuscript I ever finished, which marked something of a watershed by showing me I really could finish something of that size. Before then, I'd always had hope, which is something, but it's far less durable than evidence. I'd like to say I learned something important about how to write a novel by completing that first literary marathon, but I'm not certain that's the case. If you're trying to stretch yourself and grow thematically and ambitiously—and I certainly try—you quickly learn that each new project is a distinct challenge, with its own factors that are highly distinguishable from those that influenced previous works. I suppose that earlier quality, hope, has been replaced by faith, in that I know I've done it before and can do it again. I'm less apt to be cowed by things like hard sledding or the great murky middle, when I'm adrift in a manuscript and not yet sure how it's all going to resolve. But each project rises and falls not on past performance but on indicators I've learned to wait on: the spark of memory, the hard-bond connection to it, the imagination that gets set free, the impossible-to-ignore compulsion, at last, to sit down and start writing. Consequently, my occasional opportunities to talk to aspiring writers about how to go about tackling a novel tend toward mundane platitudes: 1. You have to start it. 2. You have to keep at it. 3. You have to bear down when it gets tough. 4. You have to keep going. Point is, I'm not gifted in the ways of teaching writers. I figured out what works for me, and even then, my success rate falls well short of 100 percent. Not everything I start gets finished. Not everything I finish is worth publishing. It's just the way of things. As for my flaccid advice above, it is, at the least, accurate. You can't write a novel unless you start writing a novel. But let's look at the other side of it: You can't finish one without ending it, either. My favorite moment in the process of drafting a novel comes fairly late, when at last I see not only where the road ends but also a clear view of how I'm going to get there. When, exactly, this moment comes is variable. Sometimes I see it from the distance of thousands of words and have to buckle up for a long ride to it. Sometimes I don't see it until I'm almost on top of it, rather like rounding a bend and seeing your destination city laid out and sparkling before you. Whenever the moment comes, it heralds an important development: I'm going to finish the first draft of this thing. First drafts lead to second drafts, which are my favorite part. That's when I find out whether this thing I've done is worth a damn. I've never made much of a secret of this: I often know how a story will end before I write the first word of it. Now, I'm not always right. But I often am. In the case of 600 Hours of Edward, I knew every word of the last line before I wrote any of the other 70-some-odd-thousand words that precede it. And sure enough, when Edward got there, the ending I envisioned was waiting for him. I had no expectation that such a thing would happen again—hell, I had no expectation that there would be a second novel—and that lack of assumption has served me well in the inevitable cases of endings that never come because I can't get out of the muck and arrive at them. But it has happened occasionally, a function of cinematic thinking, I believe. When I write, I'm also cueing a movie that never gets released and plays for an audience of one: It's an interior visual guide to the look and feel and tone and quality of the story I'm trying to write. Even when Edward was just a flicker of a thought, I could see an ending for him. The struggle lay in getting him there. I had no idea how to do that. That's the voyage of discovery that makes the whole undertaking worthwhile. Here, then, are nine novels' worth of endings (I'll leave the ending of Dreaming Northward to you, sometime this coming spring), along with any interesting (or not) details about them (click the covers to learn more about the books):  "All I have to do is look both ways and cross." As I said above, these were the 11 words I knew when I began to write Edward's story on Nov. 1, 2008. What the rest would be was a delicious mystery that I hoped I could solve.  "And still I wondered: If my children someday learn my secrets, what will they think of me?" I'm not a father (except of pups and kitties), but a couple of times, I've had to find my way with a character who is. Mitch Quillen was speaking clearly to me by the end of that book.  "I know she is." Despite Edward Stanton's love of language, my dude tends toward the simple observations. In the second novel featuring him, he ended with brevity. I didn't see it coming.  "I know this much, too: Never again will we keep our hearts waiting." I'm going to say it: This one remains a little cryptic, even to me. But sportswriter Mark Westerly said it with such finality that I had to trust him.  "His son moved closer, almost imperceptibly, and then, in an instant, fully there, and Samuel slipped a hand across the older man’s shoulders, and Sam leaned into the warmth of his child and waited and hoped for the despair to pass, as all things surely must." I got nothin'. Didn't see it coming. I love open endings, and man, is that one wide freakin' open.  "That’s a fact." Hi, Edward. Of all the characters I've written, he's the least like me but also the one who speaks most unmistakably to me. Will I write him again? If he demands it, absolutely.  "Can you believe that?" Out of context, it's a little hard to catch the nuance of what disgraced and defeated newspaper editor Carson McCullough is saying. It's pure incredulity, a good sign for his life beyond the page, I think.  "Be the ripple." As it turns out, this was Elisa's line, and I think it's just perfect. She, in fact, was the one who recommended ending the story the way we did; I'd had a different, lesser idea. Collaboration for the win!  "Even without doing the math, Max could see so many ways all of this could flow." I knew where the story for Max Wendt would end. (Max, in my opinion, goes on and on beyond the strictures of the book.) But I didn't know the words until we got there and found them shimmering on the Maine seashore. 8/26/2023 0 Comments Saturday Afternoon Craft Talk...

... if you'll indulge me:

The solitude inherent in composition is something I find absolutely indispensable to the experience of trying to write a novel. It might not be my favorite part—it's awfully hard to top the feeling of completing a first draft or holding the published artifact in your hands for the first time—but I cherish it nonetheless. If it were suddenly not a part of the effort, if writing became a spectator sport or, worse, if I were relegated to a minor participant in the whole endeavor ("AI, take a wheel"), I would just quit. Be done. The joy would be gone.

This is not to say that I believe the writing of a novel to be an iconoclastic endeavor. Not at all. By choice and habit and history, I'm alone on the first draft. The second. Maybe the third. But even then, even with those two words "the" and "end" on the last page, I'm far from being finished.

And this is where I start getting by with a little help from my friends.

Some writers swear by the workshop. If you've not experienced it firsthand, you've probably seen it in the movies. A pile of red meat in the form of pages is thrown to a group of other writers, who tear into it with equal measures of hostility and glee.

Who am I to argue? I didn't come from the academy.

I swear by the beta reader. This is someone tactically chosen to read a manuscript at a fraught point—for me, that's when I've done as much as I can do with it alone and still know in my heart I haven't done nearly enough—and provide actionable feedback on what works and, especially, what doesn't.

I choose different beta readers for different reasons, and though there have been repeat invitees over the years, the roster tends to change with the project. Three to five people, generally. Enough to get an accurate sample, to weed out the outlying sentiments, and a manageable enough number so I don't lose sight of what compelled the work in the first place. I never want to get separated from my own vision. I just want to be challenged so the work, in the end, is better. So I choose on the basis of life experience, temperament, wisdom, intelligence, and specialized knowledge about the subject matter of my work. I'm lucky to have many, many friends who fall broadly into those categories. I choose on the basis of someone's ability to separate herself from her own inclination for how to resolve something (that's my job) and instead simply articulate why she sees a problem. I've been very, very lucky in my choices for these roles. They've made my work immeasurably better. I simply couldn't do it without them.

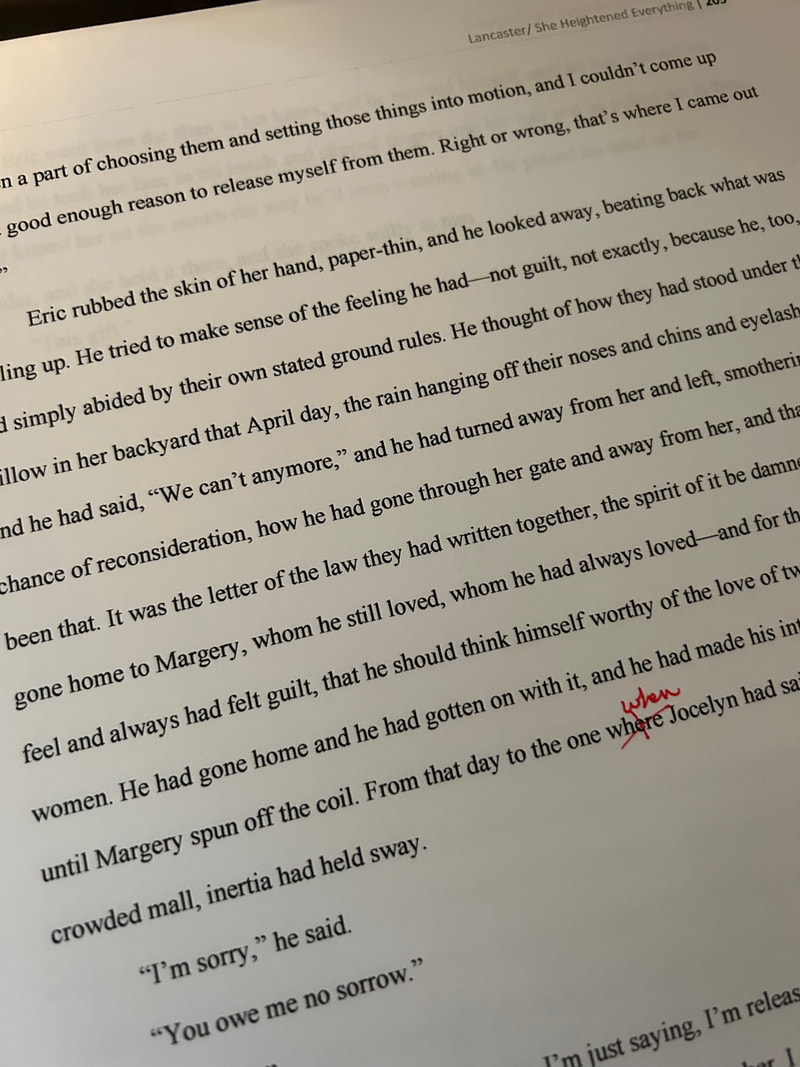

I was thinking of this today when I finally got off my duff and picked up the manuscript I'm calling She Heightened Everything, after the printout has sat for months on my office table. (You can see a snippet of it above.) Several weeks ago, one of the beta readers I asked to participate sent me her feedback, and man, was it extensive. Like I said, I've been very, very lucky.

Almost all of it was useful to me, but even that couldn't overcome my hesitation to re-engage with the manuscript. I've been preoccupied with a new job, other creative endeavors, and uncertainty about when the book in front of it is going to at last be published. (I think we'll have an answer soon.) She Heightened Everything has felt so far away from my immediate range of concerns that I've simply been unwilling to dredge it off the hard drive and get moving. But today, I felt differently about it. So I set my shoulder into it and started working through my beta reader's laundry list of concerns. I'm not through everything, and there are some things on which we simply disagree (this is inevitable and natural and fine), but I'm back in it. She's making my work better. I don't know when you'll see it, or if you'll see it, but it's better today than it was yesterday, and that's everything. Thanks, Courtney. I owe you, big time. 7/15/2023 0 Comments Saturday Morning Craft Talk**--First in a series, if I can remember to do them. I've been posting these for years on Facebook. This is a better home for them. I write fiction in a linear way (so far, at least). I start at the beginning of my idea and write, in some number of sessions, until I reach the end of it. Now, certainly, in subsequent drafts, I'll sometimes move scenes around, delete things altogether, write intervening chapters, whatever. But for first-draft purposes, to this point, I begin at the beginning and end at the end.

Several states of mind tend to accompany this not terribly unusual method of work. Among them are the thrill of having gotten started, the initial burst of industry, the where-the-hell-am-I-going-and-how-the-hell-am-I-gonna-get-there uncertainty of the thick middle, the crises of confidence, and the relief of busting through the boulders in my path. Then there's the final stretch, when I can see the end out there in the distance like a beacon but I'm still some miles away. My foot grows heavy on the gas. I rush. The care I take earlier in the draft, when I'll double back to previous chapters and scenes and buff them with a chamois cloth, falls away. I grow restless with the journey and bear down on that point in the distance, waiting for it to grow larger on the other side of the windshield. I stretch, hard, so I can feel the cocaine rush of typing "The End." Subsequently, I often find that my second (and third, and fourth ...) drafts are unbalanced affairs: light touchups at the beginning, where I've been more deliberate and careful, and massive reworking in the final chapters, where I've been hasty and over-eager. All of this is an overly long way of saying that the 500 pages I printed out in March and set on the edge of my work table are calling to me. It took me nearly eight years of start-again/stop-again work to draft the damn thing. The first third is good, for as much as I've touched it. The middle is sturdy, if in need of some polish and targeted fortification. The end? I have work to do. Back I go ... 2/24/2023 4 Comments The Best That You Can Do*

* Not just the words to a Christopher Cross/Burt Bacharach/Carole Bayer Sager/Peter Allen song.

Sorry. I had to.

Wait, strike that. I'm not sorry.  Tiffany Yates Martin, a book editor who also writes under the name Phoebe Fox. (FoxPrint Editorial) Tiffany Yates Martin, a book editor who also writes under the name Phoebe Fox. (FoxPrint Editorial)

The possible mechanical aspects of the writing life—what to write, when to write, what time to write, how much to write, etc.—are so many and so varied that I've discovered I can disagree with just about anything, given the opportunity to formulate a contrary opinion or just to wake up in a mood.

But once in a while, something crosses my desk or screen that inspires nothing but rabid agreement in me. My friend Tiffany Yates Martin—in fairness, my wife's editor on several projects, but I joined the two of them for a memorable and hilarious lunch in Austin, so I'm claiming her—wrote just such a piece earlier this week. You can read it for yourself, but here are just a couple of the stellar observations: I think there’s danger in talking about our writing in a diminishing way. Most obviously it sends us the message that our creative work isn’t that important or worthwhile. It’s just a lark, a silly little whim we pursue, but we’re not kidding ourselves that we can stand beside the actual greats of literature. And ... That means having a clear-eyed view of your work and where there may be room for improvement and growth, while also allowing yourself to be proud of its merits and strengths. Without that how can we hope to improve as artists, any more than a child who is given nothing but criticism and disapproval can develop a healthy self-image and flourish? We have to create a safe space for ourselves as artists where we have permission to fail, permission to grow. Seriously, if you are one of those "oh, I just write [whatever]" or "I just dabble" writers, go read Tiffany's piece and see if, perhaps, there's a way to recast your thinking into something that's realistic and celebratory. You create things. You conjure stories and experiences. You're awesome. Never forget it.

Years ago, after my second novel, The Summer Son, came out, it landed reviews in two regional publications that I fervently hoped would shower it with praise. I was riding high, at least from a critical standpoint, having seen my debut, 600 Hours of Edward, receive wide praise and some nice awards. I thought I'd written an even better book with The Summer Son, so I readied myself for an onslaught of plaudits.

The novel went 0-for-2 in redeeming those hopes. The review in New West was generally complimentary but cast the book as falling short of its predecessor. The review in the Missoula Independent was more of a split-personality assessment—which, interestingly, is what the reviewer accused my book of having—with effusive praise for the character development and something bordering on ridicule for the plotting. I know what my reaction was, in both cases: something deeper than disappointment and a bit short of despondency. (I suppose I'm blessed/cursed by not really giving a damn what you think of me, but I get a little bruised when my work isn't seen favorably.) It was fascinating to see reactions from my friends and colleagues. A couple called me to make sure I was OK. One told me the Independent piece was an unqualified great review, a point of view I had a little trouble accessing. (Her point, I believe, is that character development is the gold standard of literary work, and I'd won the critic over with that part of my effort. OK, then.) The point of all this isn't to indulge in ancient grudges, although if I were so inclined, I'd point out that both New West and the Independent are dead and The Summer Son still puts money in my pocket every month, so chomp on that, fellas. But I am not so inclined. The fact is, the literary life of the West is poorer for those publications' absence, no matter how wrong they were on occasion. (OK, maybe just a little jab.) No, seriously, my point is this, and it's one I've made again and again: If you want something you can influence with regard to your work, better to forget how it'll be received, whether it will sell, if it'll make you rich, and put all of your attention on doing the absolute best work you're capable of undertaking at the time you undertake it. If you do that, if you're certain it's the best that you can do, you will owe no one anything. You will owe only yourself, and only this: growth, the gumption to try even harder the next time, a willingness to stretch yourself beyond what you think is possible. Some years after those reviews, I was talking with the guy who wrote the one for New West, a good friend of mine and a damn fine writer, and told him he'd certainly been right about certain things. I'd grown. I could see flaws I didn't see at the time I wrote it. I said something like "if I could do it over again, I would." And he set me straight: "Don't ever say that about your own work. Don't ever put it down." Absolutely right. You made that. Love it for what it is. Save "I should have done better" for next time, then do it. 1/15/2023 0 Comments Memory + Imagination = Fiction Elisa and I took our new presentation, title above, out for its first spin Saturday at the Stillwater County Library in Columbus, Montana. (Cool side note: The centerpiece pictured here was on our table at Grand Fortune, a Chinese restaurant in Columbus that we hit before the event. I can definitely say that's a career first for me. For Elisa, too.) To say that we were thrilled with the response to our program would be, perhaps, to diminish the meaning of "thrilled." We had a group of about 20 people who dug in with us, asked excellent questions and provided terrific insights, and even gamely took on a writing exercise at the end. The idea was to take The Word—the go-to warmup exercise I've written about from time to time—and apply the principles of memory harvesting to create the short fictional work that resulted. So we had the folks give us a passel of words, then we ran a random-number generator to choose one that would apply to everyone's work. That word: hayloft. Elisa and I wrote along with everyone else. I had the advantage of my laptop, so I was able to write about 630 words in the 20 minutes of the exercise. As I told everybody afterward, if the current manuscript took on words that quickly, I'd be done with it back in November. Of 2020. What follows is my effort ... HayloftMom told me I would be sorry if I didn’t go, if I didn’t see where my grandfather, her father, had grown up. I was dubious, to say the least. I liked our hotel, I liked the pool—the pool was about the only thing that made southwestern Minnesota in summer bearable to me—and I wanted to stay. She insisted that I go. I was nine. Guess who won that debate? The whole way over, our 1978 Chevy Citation baking on the blacktop, Mom told me that she’d only been here once, long, long ago, when she was a little girl, after grandpa had come back from the war in Italy. “It was like a magical place, Jeff,” she said, and I sat there thinking she should see some better magic. “Tractors. Gardens. Corn you can eat off the stalk. A hayloft, Jeff, with a tire swing. You can launch yourself clear into the rafters and come down in a soft landing.” I harumphed. Something good was on TV, and I was missing it. We made a little turn off the two-laner and went down this rutted two-track, between two fields of corn headed for silage. I wasn’t going to be eating anything off these stalks, I figured, but seeing as how I was a civilized boy, I didn’t need anything that didn’t come in a can anyway. But maybe I could slop the hogs and shovel out the chicken coop. Boy, howdy. At the end of the lane stood my grandfather, all unfolded six-foot-six of him, encased like a sausage in denim overalls and a gingham workshirt. I’d never seen him looking like that before; the guy was a navigator for Alaska Airlines, not a goat roper, but I guess it was the same nostalgia trip for him that it was for Mom, making his way to the place where he’d grown up. Beside him, another couple—that’d be great Uncle Leo and great Aunt Darlaine, I supposed, the proprietors now of the farm. I’d never met them, I didn’t think. Mom started crying once they came into view, and I shrank down in the seat, both because they were all waving stupidly at us and because Mom cried a lot that summer, and it had become clear I couldn’t do much other than let her hug my neck. We got out. Grandpa came at us, and Mom collapsed into him, crying at a stronger pitch. He folded her in like the bear of a man he was, and he reached out with a mitt and pulled me in, too. “We’ve been waiting,” he said. “I know,” Mom said, her voice muffled by his overalls. “I don’t think I remembered how far out it is.” Leo and Darlaine, having waited their turn, moved in, too. More hugs. More crying. Pinched cheeks on me, Darlaine’s doing, as she called me a beautiful boy. Torture. Sheer torture. “Jeff,” Grandpa said, holding me at an arm’s length. “What do you have to say for yourself?” “Nothing,” I said. “Well, you’ll need to do better than that.” “Mom says you’ve got corn here I can eat,” I said. “That we do.” “Where?” I asked. “Soon,” he said. “I’ll show you. What do you think of the place?” I cast a look around, for his benefit. All of them—Mom, Grandpa, Leo, Darlaine—had a look like something major would be hinging on my answer. “I’ve seen better,” I said. And then, deflation, right down the line. Grandpa gripped me by the neck, a gesture that looked loving enough but had a little pinch to it. I’d been mouthy. I knew I’d best not be mouthy again. “Well,” he said, “maybe that’s so. But someday you’ll lose a few things, and you’ll know better.” Because part of the exercise involves sharing both the memory and how the imagination was applied to it, here's closing the circle:

The memory: Hayloft was a word that led just about everybody to a farm, in one way or another. A word like that spawns more similarities, even in a large group, than a word like, say, forgettable would. I thought of the farm my grandfather grew up on, which I saw only once, when I was a little boy. I grabbed the name of his younger brother, Leo, and Leo's wife, Darlaine, because it was easier than making up new names. But Leo and Darlaine weren't the proprietors of the farm back then. (That would have been Forrest, another brother, and his wife, Margaret.) Everything else is imagination ... The imagination: Jeff's grandmother is conspicuous by her absence. My grandmother lived until 2017. Jeff's father isn't in the picture. Mine, both of mine, definitely were and are. I can't say I wasn't mouthy, or even that I don't remain mouthy, but I wasn't mouthy like that. I don't remember a hotel. Pretty sure we slept in campground barracks along with the rest of the out-of-town relatives that summer. Soon after that 1979 family reunion, we started losing people, which I'm sure is why it remains so firmly lodged in my mind. And so it goes. Really cool, unexpected, interesting things happen when I do The Word. It's why I love it so. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed