|

2/7/2024 2 Comments Mind the LadderThere is a point to this, I promise, but I can't get there without first telling a sweet little story. So just bear with me, please... I've been contacting old friends on Facebook and other social sites, collecting mailing addresses. I'm having a literary reading and book signing this May in Texas, my first one in my home state in many years, and seldom does one get a chance to gather his foundational friends and acquaintances in one place and say thank you, for everything. I'm going to take that shot. The address search eventually led me to a man named Jim Fuquay, and that's where both the sweet little story and the point come in. Jim, an avid gardener, told me he was fighting the doldrums of February by reconnecting with old friends, that it had been a nifty little coincidence that I had reached out when I did. He asked me to give him a call, and I did, and let me tell you, it's been a long time since I enjoyed a half-hour as much as I did that one. But that's not the point. Jim was the first person to give me steady work in my first chosen field. It's been many years since that happened—thirty-five of them as of November of last year—and we both are, to state the obvious, much older now. We established on the call that he's eighteen years my elder (I honestly never knew the age gap, only that when we met, he was a fully mature man and I was...not). Eighteen years doesn't seem like that many now that I'm breathing heavily on age 54, but when I was eighteen years old and standing in his office, asking to be turned loose on writing newspaper articles, he sure seemed like an elder. An exceptionally kind and accessible elder, yes, but an elder just the same. Here's how I described Jim's decision to hire me in a public lecture I gave several years ago: The month before, I’d answered an ad in the Star-Telegram seeking correspondents for weekly community sections of the newspaper. I was eighteen, and the hiring editor wasn’t much interested in me until he read my clips. ... He gave me a job: the lowest-level, worst-paying, crappiest-assignment kind of writing job there was, but a job. Our deal was that I’d keep plugging away at school, he’d feed me a story opportunity every week or so, pay me $50 per, and let me build up a body of work. By late December...I had a story on the front page of the main newspaper. I was 18 years old, and I’d climbed a mountaintop of sorts. I wasn’t in the place I’d wanted to be, and I hadn’t made much headway into my half of the bargain with my boss, but I was getting somewhere. So many somewheres, as it turned out. During our phone call, I couldn't help reflecting on something that has crossed my mind plenty of times in my long working life, when I've considered how I got from there to here (and all the destinations in between): Jim didn't have to hire me. He could have given me a cursory look and sent me on my way, and his life would have been continued apace. Mine changed that day. A life has some number of true turning points, and that was one of mine. What Jim did that was so kind, so basic, and yet so uncommon is that he took a good look at me and imagined what I could be rather than fixating on what I was not. I was eighteen; I had no track record. I had only potential and gumption. Jim said yes to a kid who badly needed to hear that word. This is my point. And this is my plea: If ever you're in a position to take a gamble on someone, to surprise someone with a "yes" when you could save yourself time and aggravation with a brush-off, breathe that "yes" into the air. It could be the break that unlocks everything else for the recipient of that welcome word. I talk about this a lot with a friend with whom I lunch regularly. Where is the ladder anymore? What's a kid who doesn't emerge from the traditional mold supposed to do? What is a career and how does anybody get one?

When I was eighteen years old, in 1988, I was audacious in seeking a job, but at least I knew where to look. I had my eyes on a journalism career, and the procession into one was fairly well established at that point. You went to college. You gathered some experience. You did an internship. You caught on somewhere and started swimming. If you didn't read my public lecture, linked above, perhaps take a look now. I inverted that formula. More than that, I yanked it up by its feet and bounced it off its head. I bombed the college part, eventually. Internship? Never had one, at least not in a traditional sense. Experience? Not so much, no, not at that point. I came to Jim that fall bearing clips of stories I'd written for my high school paper. Not exactly a bastion of journalistic excellence. I came to him with chutzpah because chutzpah was all I had. Still, he said yes. He knew where the ladder was, knew he'd climbed it himself, knew the responsibility he had to make sure it was in good stead for someone else. He'd gained some latitude in his profession and spent some of it on me. A simple word, "yes," with fraught possibilities and potentially difficult outcomes. But what's the good of having a "yes" in your pocket if you're not willing to draw it out and slap it on the table? As we rang off, I thanked him for taking a chance back then. "I've never regretted it," he said. Neither have I, Jim. Neither have I.

2 Comments

2/3/2024 0 Comments Texas.I moved to Texas when I was three years old. No one consulted me, and I wasn't happy about it, but Texas and I, we found our way. In time, I came to view that move as the most consequential event in my life. When I left Texas for the first time, I was fifteen years old, about to be a sophomore in high school, and I made a snap decision that I'd like to live with my father in rural New Mexico. He'd just been through a divorce, a particularly bad one, and I thought maybe he needed me. It didn't take. A lot of lessons in that, some that got under my skin immediately and others that steeped for many years before I understood. Among the latter group, probably one of the most important lessons: You can't fix for someone else what he must mend on his own. By the end of December, I was back home in North Texas, where I belonged, even if I still felt the fit was a little tight. When I left Texas for the second time, I was twenty-one, and I pointed my nose toward just about the farthest-away dot on my map. I went to Kenai, Alaska, for a sports editor's job. That didn't take, either--though some vital friendships did—and I came scurrying back not six months later. When I left Texas for the third time, I was twenty-three, and it was a job I left behind, a fairly miserable nine-month stint in Texarkana. Texas and I, we were living together uneasily amid irreconcilable differences. I worked at night on the Texas side, then hustled back across the line to Arkansas to set down my head. When I had a chance to leave Texas, off to Kentucky I went. When I left Texas for the fourth—and, as yet, final—time, I was thirty years old and adrift, in the midst of one of those Worst Years Ever that seem to surface every decade. I'd bounced from San Jose to San Antonio, and I'd found Texas to be what it always had been: inscrutable, beautiful, alluring, interesting, and not for me. Back to San Jose I went, but first with a three-month misdirection in Olympia, Washington, and it's like I said: bad year. This is all to say that I've left Texas a lot. But Texas has never left me. The math doesn't lie. Texas had me for most of eighteen years, then nine months, then eight months. Nineteen and a half years, let's call it. Add in various visits over the years—can you really leave a place that harbors your parents and your siblings and your formative memories and some of the best friends you've ever had?—and the total still falls short of twenty years, but let's round it up. Fine. Twenty years of Texas. I'm fifty-three, and on the cusp of the next number up. The scales tip heavily toward everywhere else. Here before too long, Montana will sink its years deeper into me than Texas ever did. It already has more of my heart, more influence on my creativity, a bigger share of my identity. Still, Texas abides. Still, Texas claims me. Still, I claim Texas. Those holds are coming up through my work first, which means they're coming up in my memories. My latest work is drenched in Texas, even if most of it unfolds farther north. There was no way to imagine Nathan Ray, the central character of the ensemble, without first cozying up to the Texas I knew as a boy, then conjuring a backstory where the Texas he knows is a backdrop of pain and disillusionment and gifts he cannot yet see. It's in the next book—the one with a title in flux, the one that may emerge in 2025, or maybe '26—that Texas takes a star turn, a place both abandoned and returned to. Here's a snippet: Texas was gone, falling behind us a mile a minute, and I was relieved and scared all at the same time. You leave Texas little by little and then all at once, yes, but Texas is also a magnet—a big, southerly magnet pulling at everyone else in the country with myths and manufactured romance and jobs and cheap living and low taxes. You can get away, but can you ever really leave? My answer, beyond the bounds of fiction? It's complicated. You can leave, sure. But you come back. The only thing is, I've never made a return stick. But it's early yet. I'm still upright and breathing. In the foreseeable term, of course, I'm not going anywhere. I live in Montana, I love living in Montana, and the father with whom I couldn't live in 1985 really does need me now. He lives in Montana. As long as he draws breath, and probably longer, here I'll be.

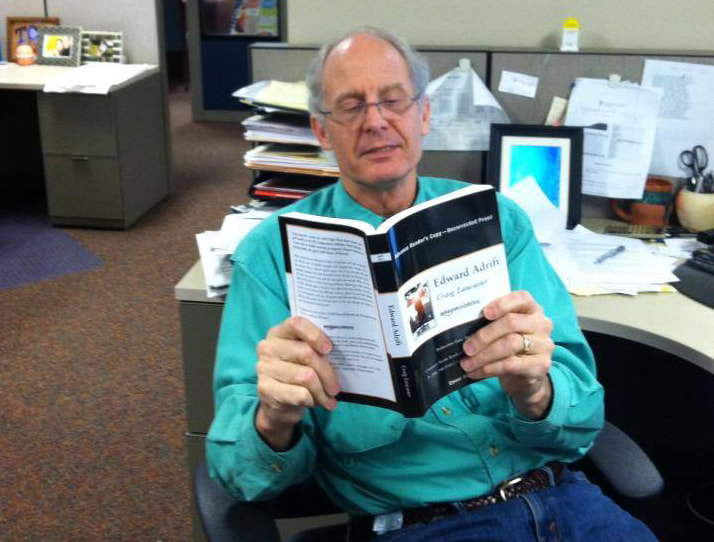

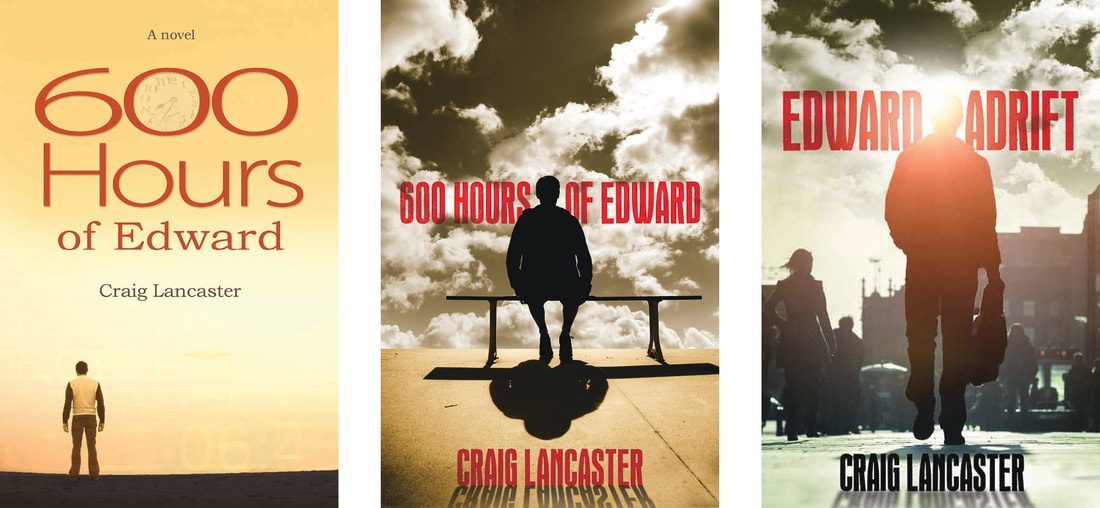

But I can't quit Texas, and unlike the answer I'd have given you twenty years ago, I don't want to. It's in my head and my heart and my memories, and the last of those is the most essential ingredient in doing this thing I do. That, I believe, is why Texas seems so insistent these days, like a song that I can't get out of my ears. It's having its say in my work, and I'm making room for it there. Perhaps, in some future I cannot yet see, I'll make other accommodations for it, too. Occasionally, either not knowing my history or not caring, a friend or acquaintance will say something cutting about the place that shaped my boyhood, and thus my life. And I'll cringe, because the cuts are easy enough to administer when Texas serves up such ridiculous stereotypes, such a bloody history, such casually cruel politics. On a day when I can find patience and indulgence for a friend's carelessness, I will say, OK, yes, but Texas is also a vast and beautiful place, full of beautiful people who contain multitudes. Texas isn't made for anyone's tidy little box. It's destined to spill out from whatever attempts to contain it. In short, it cannot be seen in simplicities when its complexities abound. 5/19/2023 2 Comments Hey, Craig, I Have a Question ...Welcome to the first installment of what I hope can become an occasional series here: You pose a question, and I answer it. Today's question came unprompted from a Facebook friend, and the answer illuminates an interesting little side story to the Edward series of books. Let's dig in: Q: I started reading 600 Hours of Edward yesterday, and in one edition I have he mentions the Billings Gazette, but in another it's the Billings Herald-Gleaner. Since this is a rare occasion when I can ask an author a question I have about a book when I have it, why is that? I don't know that I've ever addressed this in a wide-open public forum before. To grasp what happened here, we must go back to the writing of 600 Hours of Edward. That's a long time ago (late 2008) and far, far away. (OK, not really. I wrote that book about five miles from where I sit right now.) In late 2008, when I was writing the first draft of 600 Hours, I was working nights at the Billings Gazette as a copy editor. I saw no problem with using the actual name of the paper in the manuscript. The paper was a small part of the story, and the invocation of the paper's name was benign. Nobody got impugned. Also, at that point, I had no way of knowing that this one story I was sort of writing on a lark would ever be published. The idea that it might someday grow into what it became, spawning two subsequent novels, would have been preposterous to allow into my head. So ... let's fast-forward to 2012 ... 600 Hours has been out for a few years, and quite unexpectedly, it has become a little underground success story. It hasn't sold many copies, but it has received a couple of nice awards and some good press. The original publisher, a small press here in Montana, has decided to sell the publication rights to a much larger publisher with an international footprint. This larger concern acquires those rights with the idea that it will release a brand-new version of the book in August 2012, followed by the sequel, Edward Adrift, in 2013.

Edward Adrift, as I don't have to tell anyone who's read it, features the Billings newspaper as a much bigger plot player. And the references are far less complimentary. My problem: At this point, I still work at the Billings newspaper. Not good. Not comfortable. So I reach out to my new publisher with a suggestion: How about we change the name of the newspaper in the original story to something entirely fictitious (that right there is what we call plausible deniability!) and carry that new name through the sequel? Thus was born the Billings Herald-Gleaner (because if you're going to put a fake name on your newspaper, make it a funny one). I did realize we would leave some readers confused, but frankly, it's a pretty small number. I think the original version of 600 Hours of Edward sold fewer than 1,000 copies, and the 2012 re-release has sold upward of 200,000 across all of the languages in which it appears. For the vast preponderance of readers of the Edward books, the newspaper is and has always been the Billings Herald-Gleaner, not the Billings Gazette. Meanwhile, changing the newspaper's name meant I could continue to go to work without fear of having insulted my employer in a way that would have harmed either of us. A couple of final takeaways: My career at that newspaper ended just a few months after Edward Adrift was released, so I don't think changing the name of the paper in the book had any real effect, other than making me feel better about things. But there's a larger lesson here, one I've applied in the writing of subsequent books: It's fiction, so why not be fictitious? Business names, particularly, tend to be transient anyway. In an odd way, a piece of fiction can remain a lot more timely with invented references than it can with references to real-life things that might not survive a shift in fortunes or consumer habits. 10/12/2022 0 Comments The Past's PresenceEven though it's been a lively few weeks, Elisa and I have been feeling the pull of something peaceful. We scuttled our anniversary plans at the beginning of the month because Spatz the Cat was ailing, then a calendar filled with wonderful things—the High Plains Book Awards for me, a new novel launch for her—conspired against just-the-two-of-us time. Today, we grabbed a little of that, heading off on a day trip to one of our favorite places anywhere, Chief Plenty Coups State Park. There, less than an hour's drive from Billings, is a place both sacred and accessible to all, a preservation of the great chief's words and artifacts and vision. Every time we go, we take a lunch, then we visit the museum, then we take the long, looping walk around his home and his orchard, basking in the quiet and the peacefulness. A visit truly is a salve. On the drive back home to Billings, just outside the town of Pryor, I stopped for one more picture. You can't see much; the gate at the property was closed and locked, and my little iPhone camera couldn't do much with the scene.

Out there, though, is a house that once belonged to a rancher named Herman Hamilton, who is long dead and even longer not the owner of the spread. And somewhere on that patch of land where the house sits once sat a tiny little trailer home, way back in the early 1960s. It was there that my mother and father lived for a short while as Dad helped Herman tend to his ranch. The time that they lived there far predates me. They've been divorced for nearly 50 years—almost the entirety of my life—and probably haven't been in each other's presence more than a dozen times in all those years. When I'm with them in the same room, it's less a case of the gang is back together and more a case of my looking at them and wondering, "How the hell did this pairing ever happen?" (Answer: Youth and beauty and mutual desire. Move on, Craig.) Anyway, this isn't about that, not so very much. It's not even about this place that sits mere miles from somewhere Elisa and I regularly go. No, this is about the adage that gets fixed to Montana sometimes when it's described as one small town with really long streets. Herman Hamilton, you see, not only was my dad's long-ago employer but also was my best friend Bob's great uncle. Bob, whom I've known only since 2013 or so. Bob, who became friends with my dad because they both owned condominiums in the same development and were chatting one day and Dad mentions Herman Hamilton and Bob says, "Holy crap ..." The world really does shrink sometimes. (Herman was also a bank robber of some repute in the 1930s, but I suppose that's another story for another time.) 8/14/2022 0 Comments Small. Appreciative.

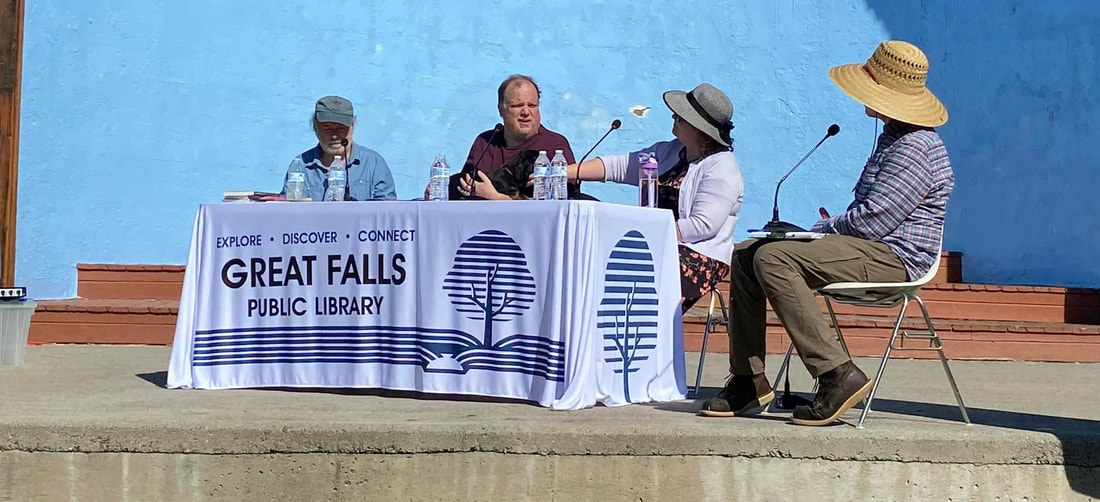

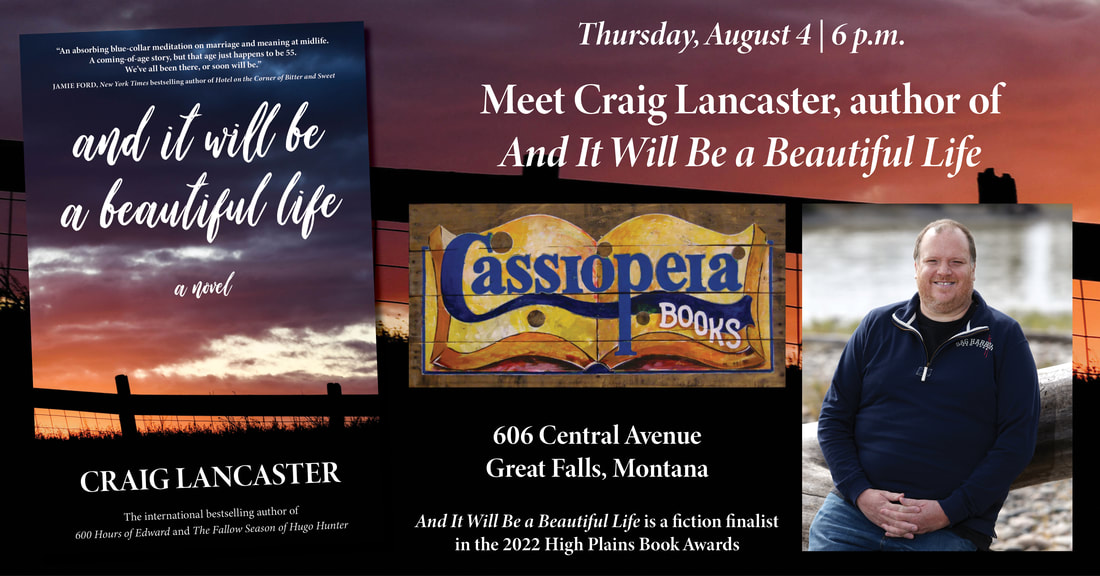

Life has some funny cycles. As I write this, I'm just a handful of hours home from a couple of days in Great Falls, that visit coming on the heels of another Great Falls trip the previous week. Before that, I think the last time I was in Great Falls other than just passing through was ... 2010? 2011? A long time ago. I hope this means I'll be going back sooner rather than later. I like that town.

I was there to take part in a panel discussion of Montana authors, sponsored by the Great Falls Public Library as part of the Big River Ruckus festival. It was a blistering-hot morning, and my planet-sized melon sizzled. As is often the case for literary events, we didn't have a big crowd (I believe the applicable adjectives are "small" and "appreciative"), but we had good times in abundance. I joined poet Dave Caserio (a Billings denizen, like me) and writer Kristen Inbody, and we had a rollicking good time talking about writing in the West, ideas, how place figures into our writing, and much more.

Whenever I do an event, I'm put in mind of a line from a Pernice Brothers song: It doesn't matter if the crowd is thin / we sing to six the way we sing to ten ...

It's a funny line, of course, but the sentiment is dead-on. I've seen everything there is to see at readings, book signings, and the like: small gatherings, no gatherings, full houses, whatever. Whatever you get, you deliver as best you can to whoever was kind enough to show up. It's a charming business in that way. Every hand that's there to shake—or the only hand that's there to shake—is another chance to make a connection. And connections are everything. One person showed up? Great! Take that person out for dinner or a drink. The whole town showed up? Fantastic! Now you've got a party.

Love is love, and we love the stage ...

Before heading home Sunday, I drove out northwest of Great Falls to see the dairy farm my father grew up on. It was only the third time I've been there, and the second was just a drive-by, but I remembered the route just fine. I drove down the long driveway to where the house is, but nobody came out, and I wasn't about to go knocking on doors, so I took a quick look, then slipped out of there quietly.

Here's a nice shot from atop the bench, about a mile and a half from the farmhouse. Sorry for the telephone pole bisecting Square Butte.

When I talk about writing and where it comes from, as I did during our discussion Saturday, I'm apt to talk about how we are born with stories. We're not blank slates. Going to a place that was formative for my father (in mostly devastating ways, unfortunately) is a good demonstration of what I mean. It allows me to put eyes on his life, to process it, and to make sense of my own. Because of the way his life was shaped by his early experiences, he had a story to transfer to me, one that I would start to carry when I came into the world, along with the one I would live out in my own days. The same is true, of course, with my mother, and her parents, and his parents, and their parents before them, and on and on. The stories are inside us, already coded. We draw them out, interpret them, weave them with imagination and memory (in the case of fiction), give them purpose. It's a beautiful thing. Even when the underlying material is made up of mostly terrible things.

"Before you climb the mountain, first the foothills must appear."

It was a long, hot, empty drive home for Fretless and me. He mostly slept. I mostly sang along with the random shuffle of iTunes, something I can get away with when I'm alone. (I certainly wouldn't subject any human to my singing voice.)

On the final stretch home, I received a particular delight when iTunes served up one of my favorite songs but also one that doesn't often swim to the top of the heap. I suppose most songs remind us of something, someone or some point in time. Certainly, this one does that for me. There's a tinge of melancholy, though, because it's a reminder of a friendship I miss. It's been many years since it went by the wayside, and I've come to embrace something I was told a long time ago when I was seeing a counselor while in the midst of divorce: Some friendships are like cab rides. They have a beginning and an end. Indeed, they do.

Anyway, it was nice to hear the song at that moment, with my head where it was (reeling in other memories), to recall good times with someone who was a good friend, and to put out a silent wish: I hope the good life has found you where you are.

It certainly has found me. Coming home—to Billings, to Elisa, to Spatz the cat—is the best arrival I've ever known. It makes the leaving worthwhile. 8/5/2022 0 Comments Great Falls, AdequatelyCome October 1st, it will be six years of marriage and about seven and a half years of togetherness for Elisa and me, and let me tell you: That's long enough that most of the stories have been told, mine to her and hers to me. We scooted away for an overnight trip to Great Falls this week. I had an event at Cassiopeia Books and an overdue acquaintance to make with owner Millie Whalen, and it was nice that Elisa and I could get away, just the two of us, for a little while. On the trip home, one of those untold stories spilled out ... Great Falls is where a lot of my family lore resides—my father, born in Conrad, grew up around there, and he and my mother married there long before I showed up—but it's not somewhere I often go. In nearly sixteen years of living in Montana, I've been only a handful of times, far less often than I've been to Missoula or Bozeman or Livingston or Helena or, heck, Miles City or Glendive. But in 1992, I almost moved there. That's the story that had gone untold. Now, when I say "almost," some qualifiers are in order. I wanted to move to Great Falls (or thought I did). The sports editor at the Great Falls Tribune at the time, a wonderful guy named George Geise, wanted me to move to Great Falls. The man who could make it happen, a senior-level editor at the paper I'd just as soon not name (but whose name I've never forgotten), made it clear I wouldn't be welcome there. The reason: I didn't have a college degree, and he didn't think I was qualified for the job without one. (I still don't have a sheepskin, but that's another story.) Now, let's be clear: This guy was flat-out wrong. I could handle the job I'd applied for (sports copy editor/page designer). I was handling it at a paper of similar size in Texarkana, Texas, and I would go on to handle it at progressively larger, more prestigious papers. I would, in time, become well-decorated and well-traveled. I would lead workshops in editing. I would direct a large sports department at a large West Coast newspaper. I would ... but I hadn't yet. Not in 1992. Then, I was a 22-year-old kid with some talent and, in fairness to the Executive Who Shall Not Be Named, some cockiness that was a bit out of proportion to the skills I'd honed to that point. And that imbalance, I think, would have been a perfectly valid reason for him to say, "Sorry, kid, not going to happen here." But that's not what he said. He fixated on the degree I didn't have. I didn't get the job. George Geise was disappointed. So was I. There was personal history to unearth in Great Falls, and I was already well in love with Montana, an affair that goes on and on. I thought I was missing out on something important. So, stuck for a while longer at a job in Texarkana I no longer wanted*, I made a resolution, one that has stuck for 30 years: No way was a guy like that going to be right about me. I made sure of it. *—In Texarkana, the single most appalling moment of my journalism career, now more than three decades old, happened. When Magic Johnson rejoined the NBA after his HIV-positive diagnosis, I played the story big on the front page of the sports section (as did just about every paper in America). The next day, a copy of the page was in my mailbox, the story circled in red pen, along with a note from an executive at the paper: "Magic Johnson is an immoral HIV carrier, and none of our readers care about him." I should have quit on the spot. It's to my eternal chagrin that I did not. I did, however, start looking for a new job immediately.  Me with Zula (RIP), clowning around in Great Falls in 2007. Me with Zula (RIP), clowning around in Great Falls in 2007. Now ... Did I miss out on something by not finding my way to Great Falls in 1992? Well, yes. Something. But not everything, and not the most important things. I didn't make it to Montana and stick here until 2006, when I was 36. Within a couple of years, I was writing books, something I'd have not even attempted 14 years earlier. By the time I got here, I'd already dug into the personal history that was faintly compelling me in my early 20s. I'd found my grandfather and closed an open question. I'd begun to talk to my dad about his life and his memories, so I could find ways to get closer to him. In subsequent years, I'd help, in whatever meager way I could, to put ghosts to rest. The headstone pictured below on my grandmother's grave (in Great Falls) went in just 15-plus years ago, well after her death, as my father began to forgive her for the ways she'd wronged him, a thawing of feelings that came about because he and I started digging in the hard soil of his past. On some level, I'm just guessing, but I doubt any of that would have happened the way it did if I'd shown up in Great Falls at the callow age of 22 and burned through that job the way I burned through others during that time in my life. Montana might have been over and done with before I could have gotten to know her. I might have missed the best years I've enjoyed here. The very best years of my life, as it turns out.

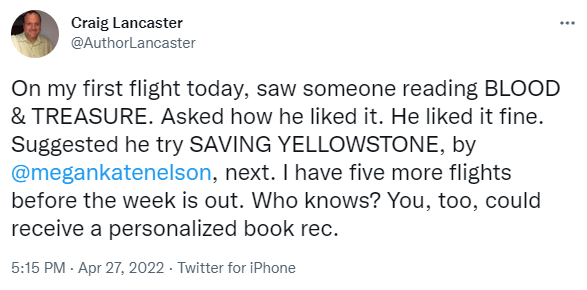

So far, anyway. 5/20/2022 0 Comments History as I Wish I'd Learned It Several months ago, one of my journalism and writing heroes, Tom Zoellner, invited me to review Saving Yellowstone for the Los Angeles Review of Books. I was a bit cowed by the prospect, to be perfectly honest. I don't have any standing, in senses literary or academic, to critique the work of Dr. Megan Kate Nelson, the book's author. I hadn't yet read her previous book, The Three-Cornered War, which had been a Pulitzer finalist. I was, upon first consideration, well out of my depth and not particularly inclined to take on the assignment. And then I reconsidered. If Dr. Nelson's literary ambition is to peel back history and explain it to a general audience—as well seems to be the case—then I'm about as general as they come. I'm curious and informed, I live in the region where the events of Dr. Nelson's book unfolded, and I try to live my ideal that an engaged life and mind require making some inroads into all you don't know (a considerable pile for me) and challenging those things you think you do know (also a considerable pile). In those ways, I was redeemed by reading and reviewing Saving Yellowstone—and by backtracking to read The Three-Cornered War. The review speaks for itself, I think. Beyond the completion of my assignment, the book has stayed with me. I've repeatedly recommended it, in sometimes obnoxious ways (see the tweet below). I've put it in the hands of friends. I've pondered the way Dr. Nelson's presentation of history—as something connected, something that breathes and reverberates—stands at odds with the lessons of the garden-variety public education I received in my Texas suburb, in which events were stand-alones and dates were to be memorized and regurgitated. Dr. Nelson's book details the Hayden expedition into Yellowstone, yes, and the establishment of our first national park, but also so much more, including the influences of capitalism, the literal and figurative erasure of Indigenous peoples, how the grappling with Reconstruction was not just a southern story but also a western one. One of the jarring lessons of the read, for me, was seeing the way the Grant administration's attempt to bring freed slaves into the body politic lay parallel with a policy of dispossession and extermination of Indigenous peoples in the West. The aims of the former policy largely failed; the aims of the latter were vastly realized. The result of both has been lasting inequality. The book is a triumph of dot connecting, of context, of presenting the bigger picture that lies outside conventional framing. It cannot be read without the realization that the fracture points of yesterday linger today. In the reading, I was reminded of something I often impart to editing clients when I sense that their narrative has gone passive (something that is NOT an issue for the history Dr. Nelson illuminates or the way she goes about telling it). The "and then, and then, and then" structure of storytelling will not compel an audience's attention or investment. I mentioned the polished-up version of history I absorbed and spat out for tests in my youth. That's how it was often (not always, but often) presented to me: Here's this. Here's this. Here's another thing. Here's still another. Hey, why is your head down and what's with all the drooling? Dr. Nelson's book, a work of scholarship, clicks along the way good storytelling does. It has sinew and electricity and a heaping measure of "but therefore ..." It moves. It speaks. It is kinetic. You must read this book. Yesterday, I drove from Billings to Livingston to see a lecture by Dr. Nelson and by Dr. Shane Doyle, who detailed the fascinating history of Indigenous peoples in Yellowstone.

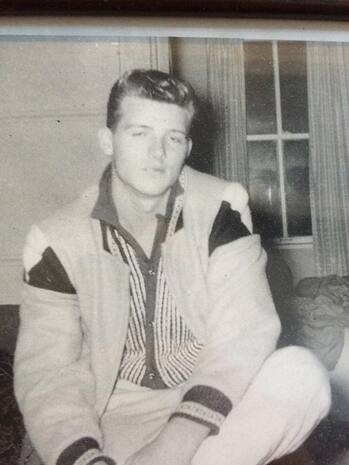

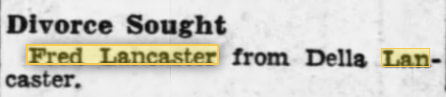

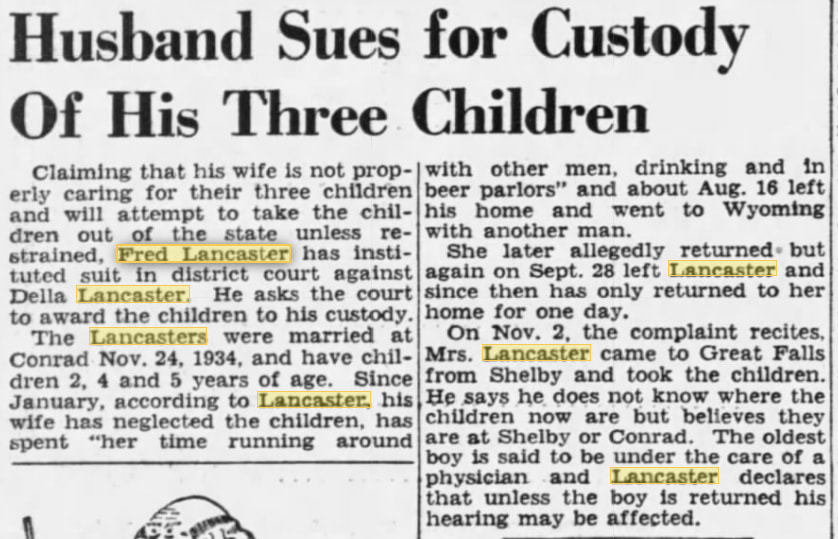

Their presentations were sponsored by Elk River Arts & Lectures and the Park County Environmental Council and served as a fundraiser for the All-Nations Teepee Village, an event "to honor and recognize the many Tribal Nations with connections to Yellowstone and highlight the indigeneity of the landscape." To learn more about that effort (and to donate), go here, please. I've been in Montana for a while now--much longer in my heart than in my physical presence—and every day that has included a trip to Livingston can be filed away under the heading of "Best Days." Beers and yuks with the great Scott McMillion (who wrote the quintessential Livingston appreciation). A quick bite and more imbibing with Marc Beaudin. Chatting with Elise Atchison and Max Hjortsberg and Tandy Miles Riddle. Seeing pals on almost every corner. May your life be blessed with interesting travel and good friends. 7/13/2021 0 Comments Down the Rabbit Hole …... and into the rest of the story, or at least more of it. I've been on the masthead of Montana Quarterly for the better part of a decade now. But back in 2010, when I had one novel to my name and not much else in the way of published literary work, I was just a guy pitching an essay to Megan Regnerus, then the magazine's editor and now our beloved editor emeritus. I called it The Small Things, and it was written after my father, Ron, and my Uncle Bob Witte (RIP) ventured out to the Fairfield Bench, near Great Falls, and found the dairy farm that shaped Dad's young life in some pretty horrible ways. I won't say much else here; you can read the piece for yourself, and I hope you will, because it provides a good anchoring for some discoveries I recently made while digging through archives. Long story short: I've always wondered about some of the details my father told me that day on the bench, not because I thought him dishonest about the general gist of things, but because he was 71 years old (he's 82 now), and that's a lot of time for the finer points to get lost. But he hadn't lost them. Not really. Let's dig in ... From the piece: "I’d heard, or maybe I’d assumed, that my paternal grandfather, Fred, had walked out on the family when Dad was two or three years old. But here was Bob, telling me that it had been a proper divorce and that Dad’s mother had rejected the children." The archives say ... Pretty much dead-on, if Fred's account of it is to be believed. He sought the divorce. He also tried to get the children (Dad, his older brother Duaine, his older sister Dolores). From the piece: "When Fred showed up to get Dad a week later, Dick locked the little boy in the basement and met Fred at the road. He carried a shotgun, all the better to send Fred on his way. Three children could accomplish a hell of a lot more work than two, and Dick aimed to keep Dad close, be it with a gun or a fist or a horse whip." The archives say ... Nothing I found speaks directly to this episode. Still, I'm not about to contradict Dad; he remembers it, he's shaken by it all these years later, and trauma has a way of imprinting itself immutably. What I know for sure is that Fred and Della and the man who became her new husband, Richard Mader, had confrontations. Here's the evidence: I've saved the best one for last. The remembrance of my father that was shrouded in the most mystery was where he went and what he did when he finally ran away from Richard Mader's dairy farm for good. Dad's memory is that he went to work for a farming family near Three Forks. I had no reason to disbelieve him, of course, but Three Forks is a fair distance from Fairfield. I wondered how he got there and whether he might have actually ended up somewhere else, somewhere closer, and just lost the place to the intervening years. Nope. From the piece: "After a few weeks, he ended up on a farm in Three Forks, doing odd jobs and being attended to by a kind family that kept him shielded from Dick, who was still looking for him. After a year or two, Dad told the farmer that he would like to see his father again, and the man agreed to find Fred and take Dad to him. A few weeks later, word came: Fred was in Butte. "More than fifty years later, Dad’s voice broke and his eyes floated in tears as he revealed what happened next. They were the only emotions he betrayed in telling the story. “'The farmer told me, "I’ll drive you to Butte and once you’re there, I’ll put you in a cab and follow you to your father’s house. Once I see that he’s come out to get you, I’m gone." ' "In a singular act, that Three Forks farmer, whose name has been lost to the intervening years, did for Dad what no one else could be troubled to do: He acted in the best interest of the child." The archives say ... Well, just have a look from a newspaper's "persons sought" column:  Dad, early 1960s. Dad, early 1960s. Getting at the details of my father's life has been a driving pursuit for many of my own days. Part of it is that I'm his only child, and if there's a story to be salvaged, it's up to me to mine it and tell it. And part of it is that I'm so heartbroken for the boy he once was, a clearly smart youngster who was denied so many of the blessings of his age, who was brutalized and stunted and who has persevered despite it all. I know how violence cycles from generation to generation, and I also know that the man I call Dad has refused to spin it on into me. It's the great achievement of his life, and he probably doesn't even know it. I want to drag the shit that happened to him into the light, the best disinfectant for what was visited upon him. He's not a hero. He is, in fact, a deeply flawed man (as is his son, as was his own father—there's more to that story, for another time). But he's my dad, and I love him. Addendum: There's an earlier piece, originally published by the San Jose Mercury News in 2004, that focuses more on finding out what became of Fred after Dad reunited with him in the mid-1950s. That was the last time father and son saw each other. Dad went into the Navy, and Fred went ... well, that's the interesting thing. You can read about that here. 6/30/2021 2 Comments They're Leaving Us Searching the cabinets in Casper, Wyoming, when I was a little boy. Searching the cabinets in Casper, Wyoming, when I was a little boy. It was after Ned Beatty died—which came not long after Gavin McLeod died, which came on the heels of Charles Grodin's death—that my friend (and best man) Jim Thomsen said, via text, "We're losing the generation we looked up to." Indeed, we are, as early Gen Xers, and there's a reason for that: We've made a right turn at middle age and are headed not away from Albuquerque but toward our own burning out. If people twenty and thirty and forty years our elder are finding the exit of this mortal coil, it's only proof that time is immutable and undefeated. We will follow them into stardust, and that eventuality is already close enough to whisper to us. My reply to Jim that day: "Dying is the one thing we were born to do." I've been thinking of that a lot—not necessarily Jim's observation, nor mine, but the relentlessness of time. It's not sentimental. It's not personal. It's not tender or caring. It just is. Every fraction of a second of every second of every minute of every hour of every day of every week of every month of every year... I've also been thinking of it a lot since finding out that my Aunt Barbara died last week. If there's someone who has been in my life from cradle to now, my parents aside, it is her. An early friend of my mother and father. The sister of my eventual stepfather. The mother of cousins, once and twice and thrice removed. I've been driving for thirty-five years, and many of those years have seen me drive into or through Casper, Wyoming, the first home I ever had, just a few houses down from where Barbara and her family lived. And almost every time, I've made a stop to see Barbara, and before that Sammy, her late husband. It's a ritual that seems inseparable from what I know to be the way of my life: If I'm in Casper, I swing by and say hello. There will be no more of it, at least no more that terminates at her front door. Time is not sentimental, but I remain so. I might still turn right off Poison Spider Road. I might still cast a glance left at the first house I ever knew. I might still wonder what my long-ago friend Richard is doing these days. I might wave at Barbara's house as I go by. But go by I will, because there's no longer any reason to stop and say hello. It's hard to part with that. Hard for me, anyway. 6/25/2021 0 Comments The Things That Need to be Said

After the second reading from And It Will Be a Beautiful Life last weekend at This House of Books, I was talking about the prominent roles of memory and reflection in writing, and I relayed the story of reconciliation with a former college roommate whom I wronged more than 30 years ago. The video above begins with the salient part.

The brief retelling in the video covers the major points. I ruined a good friendship with selfishness, and I left him holding the bag on what was supposed to be a shared obligation (rent). We never talked again after I bailed, and that sucks—the bailing and the not talking. It was not a proud moment for me, and occasionally, the memory of it has drifted through my head and shamed me anew. And I'll just say this: The occasional shame was a reasonable toll for the way I inflicted my immaturity on someone else. A few years ago, the woman who ran the student publications department at UT-Arlington, Dorothy Estes, died, and tributes poured in from all over, including one from my former friend. Long after I should have done so, I reached out: Seeing your lovely remembrance of Dorothy Estes brought forth a lot of memories, many good, some bad, and the bad ones all on me. I've thought about you from time to time these past 25-plus years. It may well be ancient history, but it's something I've left undone, so if you'll indulge me I'd like to close it up now: I'm sorry for the way I left you holding the bag on that apartment all those years ago, and for the way that effectively ended what had been a good friendship. It's been a source of shame and regret for me for many years, as well as a point of departure. In the aftermath of that, I started growing up, which was long overdue. I was telling my wife about those years this morning. The Shorthorn, and UTA, don't occupy the same place in my history as they do for so many who've come together to remember Dorothy. Those were difficult years for me—difficult in my own skin, in my studies, in owning up to the responsibilities of being a man in the world. I found my way later on, but I've certainly harbored regrets for the prior mistakes and idiocies. Again, I am sorry. I hope this finds you well. I loved your remembrance. It evoked in me something I remember often feeling when I read your stuff all those years ago: Damn. I wish I'd written that. What he wrote in response belongs to him, but I can assure you it was kind and considerate and reflective of the young man I knew him to be and the older man he'd obviously grown into. We closed the book on something between us, and I think we both felt good about that. One of the things I've learned about myself is that I crave closure, and that yearning can be good and bad. On one hand, the compulsion allows me to reconsider past encounters rather than just calcifying into positions that might not be healthy. On the other hand, sometimes situations are meant to be exited wordlessly and expediently, a true change of trajectory. Wise words from a former counselor of mine, as I walked through the rubble of a divorce: "In some things, closure is overrated." In this case, though, I think it's just what the moment required. For both of us.

Here, though, is where the story takes a turn …

I went home that night after the reading and reflected again on the original unkind act and on the subsequent, many-years-later reconciliation, and the next morning I sent my erstwhile friend a copy of the video above, pointing him toward the bit about our history. And then, for whatever reason, I ran a Google search on him. Roy R. Reynolds, my long-ago friend, died earlier this month. Fifty-three years old. Young. Far too young. I feel privileged to have known him, once. Regret for not mending the breach before we did. Gratitude that the mending happened at all, that I reached out, and especially that Roy met that outreach with grace. He didn't have to do that, but he was the kind of man who wouldn't have done anything else. Godspeed. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed