|

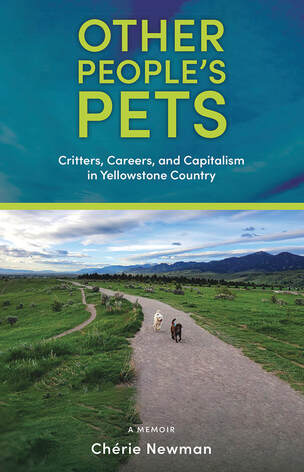

3/2/2024 0 Comments Q&A: Chérie NewmanToday, it's my pleasure to host one of my all-time favorite human beings, Chérie Newman, as she answers some questions about her book Other People's Pets: Critters, Careers, and Capitalism in Yellowstone Country.  One of the things I like best about Chérie is how deeply she thinks about things, a tendency of hers that is written across her answers to my questions (and I promise, we're getting there soon). Then, of course, I'd have to consider the other things I like about Chérie, and the list grows. She has wide-ranging talents, she's a supportive pillar of the culture she exists in, and as I know from personal experience, she'll drive a few hours to see your play. (Well, maybe not yours. But mine. Thanks again, Chérie!) I've known her for going on two decades, and I'm continually impressed by the breadth of what she dips into and becomes proficient at doing. Without further ado, then, here's Chérie Newman and her thoughts about Other People's Pets...  I'm fascinated with the resumption of your—not career, really, but work—as a pet sitter after a long break from it. What prompted that? Was it like riding a bike, as the saying goes, or were there rigors to the second go-round you didn't anticipate? The resumption of my work as a pet sitter happened during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Before March of 2020, I earned most of my freelance income as a podcast editor, working with audio files recorded during live events. Then, suddenly, there were no live events. No live events meant no money for me. My hasty reaction to the loss of income was to accept a job as an office manager. Yuck!! I do not like office work. So, I quit that after a year and agreed to become a subcontractor for a Bozeman pet sitter who had way more work than she could handle. This was the end of 2021, when many people were starting to travel again. She started sending me on interviews and that’s when the fun began. Although, I’ve taken care of other people’s pets all my life, it was mostly for friends and family. Right now, I can only think of four or five people—“clients”—who hired me as a professional, home-stay pet sitter between 1990 and 2022. The rigors, as you say, of these new situations were complicated and multi-faceted. Most of the people I worked for were nice. But they weren't paying a lot, and their expectations were high. And, I have to say, that even though they were paying me two or three times the amount I’d earned before, the average hourly rate came out to about $4 an hour. Four dollars an hour for being on duty 24/7 is not great. Especially when you factor in responsibilities for other people’s property, package delivery (Why do people order stuff when they know they’re leaving town?), invisible fences that fail and other high-stress events, and the fact that most of the houses were located far from central Bozeman. The $4/hr didn’t include fuel and other travel expenses. It didn’t include travel expenses incurred when I drove 30 miles for an interview. At what point did you realize you were gathering book-worthy material? When my friends started yelling, “You have to write a book about this!” every time I told stories about my experiences at dinner parties. I love how the book uses something as seemingly picayune as pet sitting to explore much deeper themes about where we live and how. What are the big takeaways for you regarding our relationships with our animals and the places we call home? Well, first let me say that I’ve noticed a trend: pets are now treated more as children than animals. The love-of-my-life dog, MooJee, lived with me for 15 years, but I never considered her my child. She was a beloved companion and, of course, I did everything I could to keep her happy and safe. She was dependent on me for that. But. She. Was. A. Dog. During my recent pet sitting adventures I noticed an increase in bad pet behavior. Lots of neurotic animals, made so, I believe, by their people. For example, I took care of two Irish setters whose daily schedule included cocktail weenies at 4:30 p.m. and an 8 o’clock bedtime. They also expected their lunch at 2 p.m. and acted out if it wasn’t served on time. By acting out I mean behavior such as opening the freezer and letting food thaw or dragging kitchen scraps out of the sink and throwing them all over the floor or hiding car keys under a dog bed. The places we (some of us, anyway) call home seem to be much more temporary than they were in the past. And people who have more than one house/home often leave their animals with a pet sitter while they live somewhere else for long periods of time or take pets with them and leave their houses empty. I wonder about all the huge, often uninhabited houses standing on Montana land, places that used to support wildlife, land upon which wildlife can no longer migrate or find food. What have you learned about humans through their pets? I’ve noticed an increase in the human need for external approval, which some people try to extract from their pets. Kind of crazy. Pet pics on social media attract lots of attention, which offers online validation for people. But of course, pet pictures and stories are entertaining and fun. We can’t safely post images of children online these days. Maybe our pets are stand-ins? And then there’s the amount of money people in the U. S. spend on their pets—nearly 150 billion dollars in 2023, according to Market Watch. So, your question is insightful. Are humans devolving as the status of pets rises? Are pets usurping control of our behavior and finances? What's next for you (wide-open question; I'm talking books, music, vocation, avocation, etc., etc.)? Ha! Thanks for asking. My mind is always blazing with new ideas. I just published another book, Do It in the Kitchen: a step-by-step guide to recording your life stories (or someone else’s). When they find out I’m an audio producer, people often ask me questions about recording audiobooks and oral histories, or want to know how to create a podcast. This book will help anyone who has those kinds of urges. I just finished writing a children’s book about a dog who saves his family from a house fire (true story). The process of finding an illustrator has been, well…interesting. I wish I had better drawing skills. (But maybe not because then I’d draw and I have too much other stuff to do.) My list of podcast clients has grown again during the past few months, so I do that editing/production work as it comes in. I’m also a musician and play in a band called Ukephoria Montana. We perform public and private concerts and participate in twice-monthly sing-along sessions at the Gallatin Rest Home. I participate in a songwriting collaborative and write songs on my own, as well. Every so often, I land a public speaking or workshop facilitator gig. I can’t name names, but I’m talking with an educational group about the possibility of producing a podcast series for them. It would be a dream gig for me. All fingers crossed, please. Since I’m self-employed, the marketing and PR tasks are endless. There’s always something new to learn. And, oh yeah, I read a lot of books and listen to several audiobooks a week. Yep, a week. Recent favorites:

What am I missing? What else would you like to say?

Oh, you are a brave man. I always have something else to say and usually say way too much. But I’ll stop now, except for this and this:

Wait! One more thing: Thank you for these questions and for reading my book. Oh, and another thing: I’m champing (yes, champing — to more precisely convey “impatience” — not chomping) at the bit to talk with you about your new novel, Dreaming Northward. Okay, that’s all my things. Maybe. But you should stop reading now.

0 Comments

2/7/2024 2 Comments Mind the LadderThere is a point to this, I promise, but I can't get there without first telling a sweet little story. So just bear with me, please... I've been contacting old friends on Facebook and other social sites, collecting mailing addresses. I'm having a literary reading and book signing this May in Texas, my first one in my home state in many years, and seldom does one get a chance to gather his foundational friends and acquaintances in one place and say thank you, for everything. I'm going to take that shot. The address search eventually led me to a man named Jim Fuquay, and that's where both the sweet little story and the point come in. Jim, an avid gardener, told me he was fighting the doldrums of February by reconnecting with old friends, that it had been a nifty little coincidence that I had reached out when I did. He asked me to give him a call, and I did, and let me tell you, it's been a long time since I enjoyed a half-hour as much as I did that one. But that's not the point. Jim was the first person to give me steady work in my first chosen field. It's been many years since that happened—thirty-five of them as of November of last year—and we both are, to state the obvious, much older now. We established on the call that he's eighteen years my elder (I honestly never knew the age gap, only that when we met, he was a fully mature man and I was...not). Eighteen years doesn't seem like that many now that I'm breathing heavily on age 54, but when I was eighteen years old and standing in his office, asking to be turned loose on writing newspaper articles, he sure seemed like an elder. An exceptionally kind and accessible elder, yes, but an elder just the same. Here's how I described Jim's decision to hire me in a public lecture I gave several years ago: The month before, I’d answered an ad in the Star-Telegram seeking correspondents for weekly community sections of the newspaper. I was eighteen, and the hiring editor wasn’t much interested in me until he read my clips. ... He gave me a job: the lowest-level, worst-paying, crappiest-assignment kind of writing job there was, but a job. Our deal was that I’d keep plugging away at school, he’d feed me a story opportunity every week or so, pay me $50 per, and let me build up a body of work. By late December...I had a story on the front page of the main newspaper. I was 18 years old, and I’d climbed a mountaintop of sorts. I wasn’t in the place I’d wanted to be, and I hadn’t made much headway into my half of the bargain with my boss, but I was getting somewhere. So many somewheres, as it turned out. During our phone call, I couldn't help reflecting on something that has crossed my mind plenty of times in my long working life, when I've considered how I got from there to here (and all the destinations in between): Jim didn't have to hire me. He could have given me a cursory look and sent me on my way, and his life would have been continued apace. Mine changed that day. A life has some number of true turning points, and that was one of mine. What Jim did that was so kind, so basic, and yet so uncommon is that he took a good look at me and imagined what I could be rather than fixating on what I was not. I was eighteen; I had no track record. I had only potential and gumption. Jim said yes to a kid who badly needed to hear that word. This is my point. And this is my plea: If ever you're in a position to take a gamble on someone, to surprise someone with a "yes" when you could save yourself time and aggravation with a brush-off, breathe that "yes" into the air. It could be the break that unlocks everything else for the recipient of that welcome word. I talk about this a lot with a friend with whom I lunch regularly. Where is the ladder anymore? What's a kid who doesn't emerge from the traditional mold supposed to do? What is a career and how does anybody get one?

When I was eighteen years old, in 1988, I was audacious in seeking a job, but at least I knew where to look. I had my eyes on a journalism career, and the procession into one was fairly well established at that point. You went to college. You gathered some experience. You did an internship. You caught on somewhere and started swimming. If you didn't read my public lecture, linked above, perhaps take a look now. I inverted that formula. More than that, I yanked it up by its feet and bounced it off its head. I bombed the college part, eventually. Internship? Never had one, at least not in a traditional sense. Experience? Not so much, no, not at that point. I came to Jim that fall bearing clips of stories I'd written for my high school paper. Not exactly a bastion of journalistic excellence. I came to him with chutzpah because chutzpah was all I had. Still, he said yes. He knew where the ladder was, knew he'd climbed it himself, knew the responsibility he had to make sure it was in good stead for someone else. He'd gained some latitude in his profession and spent some of it on me. A simple word, "yes," with fraught possibilities and potentially difficult outcomes. But what's the good of having a "yes" in your pocket if you're not willing to draw it out and slap it on the table? As we rang off, I thanked him for taking a chance back then. "I've never regretted it," he said. Neither have I, Jim. Neither have I. 5/15/2023 1 Comment Dan GenselFriendships are funny things. Sometimes, they exist in a fixed place and time, sturdy and strong for a particular period in our lives. A counselor of mine, Jane Estelle, once told me that human relationships are often like cab rides. They have beginnings and ends. That was wise. It's true. Sometimes, though, friendships are a ride that never ends. You don't reach a station and get out of the car. You keep going, through years and locales and jobs and other relationships and seasons of your life. And sometimes they are both. They are fixed in time and endless. Those are the best friendships. Dan Gensel was that kind of friend to me. Dan Gensel is gone. I moved to Kenai, Alaska, in November of 1991. I was 21 years old, and I didn't know anybody there. I'd come from my hometown, North Richland Hills, Texas, and had taken a job as the sports editor at the Peninsula Clarion newspaper. Why? Why not? I was 21 and unencumbered. Alaska was far away. I wanted to go and could go, and that's a combination I wasn't always going to be able to put together. Now, for example. Couldn't do it. Won't do it. Want-to isn't even a factor. Years ago, I wrote a piece for the radio program Reflections West about that time in my life and the factors compelling me to move north. You can listen to it here. My first week in Alaska, I covered a Kenai Central High School-Soldotna High School girls basketball game. It featured two of the best players in the state, two of the best players in the history of the state: Stacia Rustad of Kenai and Molly Tuter of Soldotna. On one sideline was Coach Craig Jung of Kenai, a man I'd come to greatly admire in my brief time there. On the other sideline was Coach Dan Gensel. He and Craig were great friends and ardent competitors. Stacia and Kenai were coming off a state championship; Molly and Soldotna would win one a year later. I didn't know any of that. I was just a new-in-town sportswriter, trying to figure things out. The photo above, of Dan and Melissa Smith, one of the kids I covered that season, isn't from the game in question, but it's a good approximation of the Dan Gensel of my memories. After the game, which Kenai won, he sat in the bleachers with me and just talked. Where you from? How'd you come to this job? What's your background? Getting-to-know-you stuff. I liked him, right from the start. Later, I met his wife, Kathy, and his daughter, Andrea, and liked them, too. In time, it became love. But it was like, from the get-go. Those were lonely days for me, 4,000 miles from home, alone, barely scraping by, driving an on-the-verge Ford Escort and living in a one-room apartment. Dan and Kathy took me out for my 22nd birthday, just a few months later. Dan gave me seats on school buses to far-flung tournaments and let me sleep on his hotel room floor sometimes when that was the difference between my being able to cover something and not. He also gave me a basketball education, one I tucked away, then unveiled when I wrote a short story about a wunderkind basketball player and a coach and a town that loses all sense of proportion. Here's an excerpt from Somebody Has to Lose: “Mendy, it’s like this.” He squared up to the basket, squeezing the ball between his hands and planting a pivot foot. “First option: jump shot.” Into the air he went, releasing the ball at the peak of his jump and watching it backspin softly into the net. Cash, her face red, gathered the ball and rifled it back to him. “Second option: drive.” Paul took two dribbles into the lane and then fell back to his spot on the periphery. “Third option: make the next pass.” He slung the ball to Victoria Ford, directly to his left on the wing. “You know better than to just throw the ball over without even looking.” Paul turned to the players clumped on the sideline. “Shoot, drive, pass. When you get the ball in this offense, that’s the sequence. I don’t want anybody not following it, you got that?” Yes, sir,” the girls answered glumly. "You get the ball. If the defender has collapsed into the middle, you shoot the open shot. If they’re crowding you, drive around them. If you’re covered, make the next pass. This is not difficult. Run it again.” That right there, in just a few paragraphs, is the Dan Gensel philosophy of basketball. It inverts the conventional wisdom of the time—pass first, shoot later—into a kinetic, high-scoring, fun way of playing. And, man, was he ever successful. Won a lot of games. Won a state championship. Made the hall of fame. But that's not what I remember most about him. I remember that he and Kathy and Andrea became family, particularly after I came back to Alaska in 1995 for a three-plus-year stint at the Anchorage Daily News. I remember that I was a regular guest on their downstairs couch, so much so that it developed an imprint of me. I remember that they tolerated movie nights when I'd make them watch Ed Wood and Pulp Fiction, fare that was decidedly not up their alley. I remember later visits in California and Las Vegas. I remember Andrea's wedding in the early aughts down in San Diego, when Dan asked me to give the speech before the father's speech. Predictably, I went for funny and warm, extolling my love for a family and a young woman I'd watched grow up. Dan, after me, had everybody in tears with his love for his little girl. Later, in a quiet moment between us, Dan said, "I knew you'd take them one way and I'd bring them back the other." Teamwork, baby. I remember Dan's closing out the wedding reception by climbing atop a table and lip-synching "Don't Stop Believing." I hate that song, but I love that man. I remember, a few years later, Dan's serving as the best man at my first wedding. The marriage didn't last. The friendship endured. I remember all the times we talked about getting together over the past decade or so. I remember that we didn't make it happen. That'll be the only thing I regret. It's like I said: It's a friendship fixed in time and eternal. I'll carry it now, for however long I'm around. There's been a lot of that these past few years. Too much.  It's been a long while since Dan was a basketball coach. In his final years, he was a sports radio guy--a damned good one—and a grandpa, a role he made his own in an inimitable way. He and Kathy became community stalwarts in Soldotna. Andrea and her husband, Lee, are right there. It's been a good life. It will continue to be a good life, I'm sure, but those who love Dan will have to live with a big hole in it. It's a testament to the community Dan helped me build thirty-odd years ago that one of his former players, someone with whom I've been close since I was a 21-year-old green sportswriter riding a school bus, contacted me with the news. I spent just six months in that job at the Peninsula Clarion. My Facebook page is full of people I knew then and still know now, and I'm a lucky boy, indeed. Dan was 34 when I met him and 66 when he died, and that's both a long time and not nearly enough of it. I'll miss him. 1/15/2023 0 Comments Memory + Imagination = Fiction Elisa and I took our new presentation, title above, out for its first spin Saturday at the Stillwater County Library in Columbus, Montana. (Cool side note: The centerpiece pictured here was on our table at Grand Fortune, a Chinese restaurant in Columbus that we hit before the event. I can definitely say that's a career first for me. For Elisa, too.) To say that we were thrilled with the response to our program would be, perhaps, to diminish the meaning of "thrilled." We had a group of about 20 people who dug in with us, asked excellent questions and provided terrific insights, and even gamely took on a writing exercise at the end. The idea was to take The Word—the go-to warmup exercise I've written about from time to time—and apply the principles of memory harvesting to create the short fictional work that resulted. So we had the folks give us a passel of words, then we ran a random-number generator to choose one that would apply to everyone's work. That word: hayloft. Elisa and I wrote along with everyone else. I had the advantage of my laptop, so I was able to write about 630 words in the 20 minutes of the exercise. As I told everybody afterward, if the current manuscript took on words that quickly, I'd be done with it back in November. Of 2020. What follows is my effort ... HayloftMom told me I would be sorry if I didn’t go, if I didn’t see where my grandfather, her father, had grown up. I was dubious, to say the least. I liked our hotel, I liked the pool—the pool was about the only thing that made southwestern Minnesota in summer bearable to me—and I wanted to stay. She insisted that I go. I was nine. Guess who won that debate? The whole way over, our 1978 Chevy Citation baking on the blacktop, Mom told me that she’d only been here once, long, long ago, when she was a little girl, after grandpa had come back from the war in Italy. “It was like a magical place, Jeff,” she said, and I sat there thinking she should see some better magic. “Tractors. Gardens. Corn you can eat off the stalk. A hayloft, Jeff, with a tire swing. You can launch yourself clear into the rafters and come down in a soft landing.” I harumphed. Something good was on TV, and I was missing it. We made a little turn off the two-laner and went down this rutted two-track, between two fields of corn headed for silage. I wasn’t going to be eating anything off these stalks, I figured, but seeing as how I was a civilized boy, I didn’t need anything that didn’t come in a can anyway. But maybe I could slop the hogs and shovel out the chicken coop. Boy, howdy. At the end of the lane stood my grandfather, all unfolded six-foot-six of him, encased like a sausage in denim overalls and a gingham workshirt. I’d never seen him looking like that before; the guy was a navigator for Alaska Airlines, not a goat roper, but I guess it was the same nostalgia trip for him that it was for Mom, making his way to the place where he’d grown up. Beside him, another couple—that’d be great Uncle Leo and great Aunt Darlaine, I supposed, the proprietors now of the farm. I’d never met them, I didn’t think. Mom started crying once they came into view, and I shrank down in the seat, both because they were all waving stupidly at us and because Mom cried a lot that summer, and it had become clear I couldn’t do much other than let her hug my neck. We got out. Grandpa came at us, and Mom collapsed into him, crying at a stronger pitch. He folded her in like the bear of a man he was, and he reached out with a mitt and pulled me in, too. “We’ve been waiting,” he said. “I know,” Mom said, her voice muffled by his overalls. “I don’t think I remembered how far out it is.” Leo and Darlaine, having waited their turn, moved in, too. More hugs. More crying. Pinched cheeks on me, Darlaine’s doing, as she called me a beautiful boy. Torture. Sheer torture. “Jeff,” Grandpa said, holding me at an arm’s length. “What do you have to say for yourself?” “Nothing,” I said. “Well, you’ll need to do better than that.” “Mom says you’ve got corn here I can eat,” I said. “That we do.” “Where?” I asked. “Soon,” he said. “I’ll show you. What do you think of the place?” I cast a look around, for his benefit. All of them—Mom, Grandpa, Leo, Darlaine—had a look like something major would be hinging on my answer. “I’ve seen better,” I said. And then, deflation, right down the line. Grandpa gripped me by the neck, a gesture that looked loving enough but had a little pinch to it. I’d been mouthy. I knew I’d best not be mouthy again. “Well,” he said, “maybe that’s so. But someday you’ll lose a few things, and you’ll know better.” Because part of the exercise involves sharing both the memory and how the imagination was applied to it, here's closing the circle:

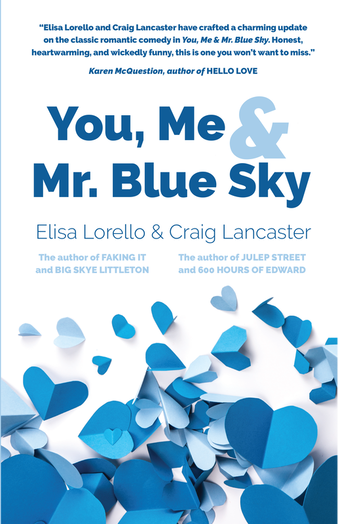

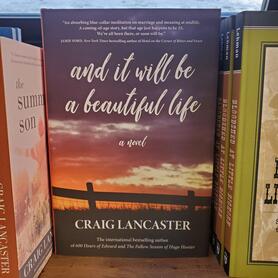

The memory: Hayloft was a word that led just about everybody to a farm, in one way or another. A word like that spawns more similarities, even in a large group, than a word like, say, forgettable would. I thought of the farm my grandfather grew up on, which I saw only once, when I was a little boy. I grabbed the name of his younger brother, Leo, and Leo's wife, Darlaine, because it was easier than making up new names. But Leo and Darlaine weren't the proprietors of the farm back then. (That would have been Forrest, another brother, and his wife, Margaret.) Everything else is imagination ... The imagination: Jeff's grandmother is conspicuous by her absence. My grandmother lived until 2017. Jeff's father isn't in the picture. Mine, both of mine, definitely were and are. I can't say I wasn't mouthy, or even that I don't remain mouthy, but I wasn't mouthy like that. I don't remember a hotel. Pretty sure we slept in campground barracks along with the rest of the out-of-town relatives that summer. Soon after that 1979 family reunion, we started losing people, which I'm sure is why it remains so firmly lodged in my mind. And so it goes. Really cool, unexpected, interesting things happen when I do The Word. It's why I love it so. So, before I go off on a burst of happiness, I should do this: In the interest of consistency and intellectual rigor, I must adhere to my basic sense that happiness, as an emotional state of being, is highly overrated. It's too reliant on current circumstance to be trustworthy, and the factors that spur it—good news, fortuitous coincidences, pure serendipity, and the like—are too transient to be relied upon. My aim in saying this isn't to knock happiness—if you have it, brother or sister, be thankful for it and keep it as long as you're able—so much as it is to cast a vote for its more durable cousin, fulfillment. If you're fulfilled in where you are, whom you're with, what you're doing, where you're headed, you have something to hold tight to when the transience of happiness is with you and when it's against you. That's my theory, anyway. That said, I'm pretty (burbly-happy curse word) happy these days. Let me count the reasons ... 1. One night in Big SkyI'm just back from Big Sky, about three hours from where I live. The board of the Big Sky Community Library chose And It Will Be a Beautiful Life as the community read (One Book Big Sky) for the fall. Tuesday night was sort of the capstone of the event. I drove out, had a wonderful chat with folks who read the book, spent the night, and came home. It was a soul restorer in all the best ways. When writers and writers gather, it can be a lovely thing (see below), but it can also be a release of the pent-up frustration that only writers know and thus are in position to help each other through. When readers and writers gather, it's straight-up love. How lucky was I to spend an evening with a bunch of people who read my book, read it closely, had such interesting things to say about it, and wanted to come talk with me? The luckiest. No doubt about it. I rode those good feelings all the way home. The drive from Big Sky to Bozeman is one of the most visually arresting things you can see anywhere in these United States, so there's that, and believe me, I drank it in (figuratively). I made stops at libraries in Bozeman, Livingston, Big Timber, and Columbus, planting seeds for more days and nights like the one I'd just enjoyed. Here's hoping. 2. The blessings of good friends With AMERICAN ZION author Betsy Gaines Quammen. With AMERICAN ZION author Betsy Gaines Quammen. I think I'm only just now getting my considerable arms around how emotionally bereft the pandemic has left me (and so many other people, judging from what I'm reading and what I'm hearing). Honestly, I thought being chased inside and away from gatherings was a small blessing amid a horrible event, but it wasn't that at all. Now that I can see and meet the people I want to see and meet—while still being careful, of course—I'm realizing how much I craved it. Just in these past few weeks, I've gotten to hang in Butte, Missoula (thank you, Gwen Florio and Malcolm Brooks), Livingston (thank you, Amy Zanoni and Maggie Anderson), Bozeman (thank you, Betsy Gaines Quammen and Kryssa Marie Bowman), and Big Sky. I've had the fellowship of brilliant writers and thinkers, genuinely good people, and people who lovingly tend to the cultural life writ large. Man. I've needed that so much. So much. Happy? Yeah, I'm happy. But grateful most of all. 3. The work is going well Winning an American Fiction Award was a lovely bit of news to receive. Winning an American Fiction Award was a lovely bit of news to receive. OK, look, here's where I keep it honest: If my publisher had said, sorry, kid, but your manuscript stinks and I'd received a lot of hate mail and my dog was snubbing me, would I be Mr. Happy? I would not. This, of course, underscores my point about fulfillment vs. happiness. I work to a standard I set so I can know I've done my best regardless of what a gatekeeper says (or, at least, so I'll have the gumption to try again if I find the door closed). I try to approach the world with an open heart because I believe that's how we get past at least some of our divisions. I engage with my dog so he knows I'm his, and he's mine. That's fulfillment. The happiness of it comes and goes. But I can't deny that I'm really, really enjoying every side of the work right now: The creation of it, when it's just me and an idea and the challenge of getting from here to there. The production of it, where I interact with the publisher I wanted to be with and who wants my work on his list. The carrying it to readers and interacting with them, which can be such an incredible validation of the work put in. The awards, both realized and potential (talk about transience). I'm as energized for all of it, the whole arc, as I've ever been. In Missoula, while waiting to eat lunch, I happened upon a meeting with a well-regarded poet and fiction writer and a genuinely good human. I don't know him well, but I like him, and even so, in the worst of my do-I-want-this-anymore crisis a few years ago, I deleted him (and a whole lot of other writers) from my social contacts, in a clumsy, flailing attempt at ridding myself of reminders of an endeavor I wasn't sure I wanted anymore. So there I was in Missoula, nonexistent hat in hand, apologizing for something I'm sure he didn't even notice, telling him I was in a dark place. He was kind and compassionate, as I expected he would be. I still appreciate the grace. I hope, the next time I'm on the other side of that conversation, I extend it to someone who needs it. I'd like to think I've learned something. Certainly, I appreciate that the want-to came back to me, and I'm going to nurture it as much as I can. But what happens when rejection arrives (as it surely will), or awards don't (ditto)? I don't know. I'll try to remember now and then and remind myself that I can be in both places. Just not at the same time. 3b. That was a lot. Here's an anecdote. So I'm driving home from Big Sky and I'm talking on the phone—hands-free—with Elisa and I'm saying much of what I said above, only differently, and I'm telling her how energized I am, and I'm hearing how energized she is, and we come around to You, Me & Mr. Blue Sky. It's the novel—a romantic comedy that goes deeper, as Elisa's work does—she and I wrote together in 2018 and 2019. We released it ourselves ... and pretty much let it flop around out there. Our crises of confidence coincided. Those were hard, broken days. We had no energy for much of anything, and certainly not for getting out and trying to introduce a book to the world. We were too adrift in our personal lives to have the fire for the professional. Frankly, there were times I wasn't sure we'd make it. But we did, and we have, and we're going to. Elisa is back, too, and she said, you know what, we should put a new jacket on that old novel we never really got behind. Freshen it up. It's a story of brightness and hope, and it has this dreary cover that doesn't fit it. Let's give it some love. OK, she didn't say that exactly, but that was the gist. And here it is, dressed to meet the readers we hoped it would meet. 4. Health Elisa didn't join me in Big Sky because our cat, Spatz, has been ailing. The most recent health issue was one that had a small sliver of hope for resolution and a rather wide, grim likelihood in terms of what we'd have to do. I had an appointment I had to keep, and Elisa decided to stay behind and tend to our girl. And our girl, not for the first time, has proved resilient. Her issue has resolved itself—or, at the very least, has recessed into a place where she's her old self again for however long that lasts. She was a surprise when she came into our lives, and we've resolved to enjoy her for as long as we have her. That horizon, delightfully, has widened. We're thrilled. As Elisa is given to saying, she's our Rushmore, Max. 8/14/2022 0 Comments Small. Appreciative.

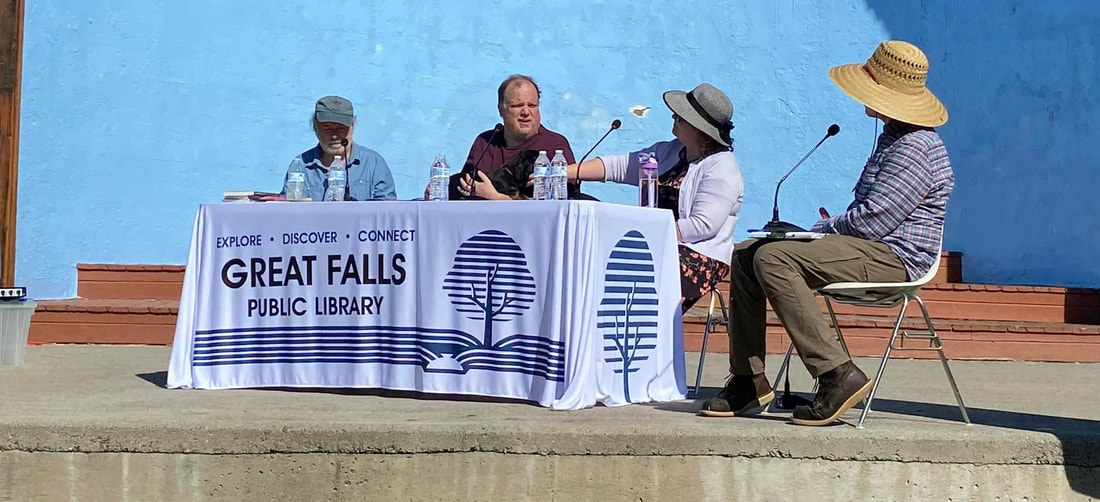

Life has some funny cycles. As I write this, I'm just a handful of hours home from a couple of days in Great Falls, that visit coming on the heels of another Great Falls trip the previous week. Before that, I think the last time I was in Great Falls other than just passing through was ... 2010? 2011? A long time ago. I hope this means I'll be going back sooner rather than later. I like that town.

I was there to take part in a panel discussion of Montana authors, sponsored by the Great Falls Public Library as part of the Big River Ruckus festival. It was a blistering-hot morning, and my planet-sized melon sizzled. As is often the case for literary events, we didn't have a big crowd (I believe the applicable adjectives are "small" and "appreciative"), but we had good times in abundance. I joined poet Dave Caserio (a Billings denizen, like me) and writer Kristen Inbody, and we had a rollicking good time talking about writing in the West, ideas, how place figures into our writing, and much more.

Whenever I do an event, I'm put in mind of a line from a Pernice Brothers song: It doesn't matter if the crowd is thin / we sing to six the way we sing to ten ...

It's a funny line, of course, but the sentiment is dead-on. I've seen everything there is to see at readings, book signings, and the like: small gatherings, no gatherings, full houses, whatever. Whatever you get, you deliver as best you can to whoever was kind enough to show up. It's a charming business in that way. Every hand that's there to shake—or the only hand that's there to shake—is another chance to make a connection. And connections are everything. One person showed up? Great! Take that person out for dinner or a drink. The whole town showed up? Fantastic! Now you've got a party.

Love is love, and we love the stage ...

Before heading home Sunday, I drove out northwest of Great Falls to see the dairy farm my father grew up on. It was only the third time I've been there, and the second was just a drive-by, but I remembered the route just fine. I drove down the long driveway to where the house is, but nobody came out, and I wasn't about to go knocking on doors, so I took a quick look, then slipped out of there quietly.

Here's a nice shot from atop the bench, about a mile and a half from the farmhouse. Sorry for the telephone pole bisecting Square Butte.

When I talk about writing and where it comes from, as I did during our discussion Saturday, I'm apt to talk about how we are born with stories. We're not blank slates. Going to a place that was formative for my father (in mostly devastating ways, unfortunately) is a good demonstration of what I mean. It allows me to put eyes on his life, to process it, and to make sense of my own. Because of the way his life was shaped by his early experiences, he had a story to transfer to me, one that I would start to carry when I came into the world, along with the one I would live out in my own days. The same is true, of course, with my mother, and her parents, and his parents, and their parents before them, and on and on. The stories are inside us, already coded. We draw them out, interpret them, weave them with imagination and memory (in the case of fiction), give them purpose. It's a beautiful thing. Even when the underlying material is made up of mostly terrible things.

"Before you climb the mountain, first the foothills must appear."

It was a long, hot, empty drive home for Fretless and me. He mostly slept. I mostly sang along with the random shuffle of iTunes, something I can get away with when I'm alone. (I certainly wouldn't subject any human to my singing voice.)

On the final stretch home, I received a particular delight when iTunes served up one of my favorite songs but also one that doesn't often swim to the top of the heap. I suppose most songs remind us of something, someone or some point in time. Certainly, this one does that for me. There's a tinge of melancholy, though, because it's a reminder of a friendship I miss. It's been many years since it went by the wayside, and I've come to embrace something I was told a long time ago when I was seeing a counselor while in the midst of divorce: Some friendships are like cab rides. They have a beginning and an end. Indeed, they do.

Anyway, it was nice to hear the song at that moment, with my head where it was (reeling in other memories), to recall good times with someone who was a good friend, and to put out a silent wish: I hope the good life has found you where you are.

It certainly has found me. Coming home—to Billings, to Elisa, to Spatz the cat—is the best arrival I've ever known. It makes the leaving worthwhile. 3/30/2022 0 Comments EmergingLike many people, I've come to loathe Facebook in as many ways as I find it an indispensable means of keeping up with close friends and loved ones. Perhaps it's the indispensability that I loathe most. I also post things there deliberately, knowing that I'll be shown them again, year after year, so I can remember certain days with some degree of precision. Two years ago, March 30 was just such an occasion. On this day in 2020, the moving trucks showed up at our house in Boothbay, Maine, and whisked away our stuff. By then, it wasn't even our house anymore; we had closed on its sale a few days earlier and were just extremely short-term renters. We loved that house. We liked Maine. But neither love nor like was enough to hold us. That's old ground that needn't be gone over again. What's hard to remember now, even two short years later, is just how frightening the whole thing was. The world had closed up. We had moving guys tromping through the house, and we—Elisa, me, the dog, the cat, my dad, his dog—kept our distance and hoped they weren't sick. Hoped we weren't sick. Wouldn't be entirely sure how to know if we were or they were. There was a lot of taking things on faith. There was a lot of handwashing and surface disinfecting. There was a lot of uncertainty about what awaited us on the road. That first night, we stayed at a hotel in Portland. I, wearing rubber gloves and a paper mask, fetched dinner for everyone and brought it back to the two rooms (guys and dogs in one, woman and cat in another). Same drill for the subsequent nights, in Buffalo and Chicago and Minneapolis and Bismarck. We limited our points of contact. I did all the gassing up for the two cars, which were similarly subdivided with occupants. I wrangled all the meals, meeting Doordash and Uber Eats in hotel lobbies. In the East, where the pandemic initially hit hardest, we stared in wonder at empty turnpikes and rest stops. The farther west we drove, the more lax people seemed about what was happening. In Janesville, Wisconsin, I turned on my heel and left a store after seeing scores of unmasked people there. In North Dakota, a convenience store clerk poked fun at my mask. In Ohio, I asked a guy to move down a urinal, and he reacted with anger: "I'm not sick." "Fine," I said, "but maybe I am." When we got to Billings, it was more of the same. We were diligent, about our hands and our faces and our surfaces. We were scared. We sequestered ourselves away for two weeks and hoped we wouldn't get sick. The unknown was a menace. We weren't alone in feeling that. It's two years hence. We're just back from a two-week vacation. We saw loved ones. We hugged old friends. We gathered with thousands in a sports arena in downtown Dallas. We crowded into a banquet hall and said goodbye to a friend. The pandemic remains with us, of course, but it's different now, too. We're vaxxed and boosted, and soon to be boosted again. In recent weeks, we've begun stepping out again. Our first sitdown meal in a restaurant happened a few weeks before we traveled to Texas. Our first evenings out to see plays (masked), too. We carry the vax cards and the masks, in case they're needed. I imagine I'll wear one forevermore in airplanes and on trains and in crowded supermarkets. I'm cool with that. It's not a burden. We've been through two flu seasons now without the flu, a first for either of us. Credit the masks. Our doctor surely does. And yet, with the specter of omicron and whatever new variants might emerge, we worry about a scratchy throat or some mild congestion. Just the other day, we broke out a test for Elisa, who was feeling a little poorly. Negative. We've been lucky. No doubt about that. But we've also been diligent. We'll try to stay so, even as we dip further into what used to be normal life. The point of all this? There is no point, really. Gratitude. Caution.

We've had a hard two years, all of us. We've lost people we shouldn't have lost. We've grown isolated and angry. We've missed things we shouldn't have missed. May we find grace. May we offer it, too. 3/23/2022 0 Comments We Who Loved JonElisa and I are just back from a two-week vacation, one spent doing all the things one should do when granted such a release from ordinary life. We saw our favorite basketball team (a loss, but whatever), we ate good food, we hugged loved ones and old friends, and we explored a bit of the Texas coast. A damn good time. And then, to finish it off, we headed to Santa Fe and said goodbye to Jon Ehret. Somehow, the world has kept on spinning since he left us on Aug. 21, 2021. He's often on my mind, always in my heart, and badly missed by everyone who grew to love him. On a late-March day in New Mexico, we raised a toast. It was beautiful. He was beautiful. And it made me wish, again, that he could have been at the table with us, noshing on good food and reveling in good memories. I met Jon when I was 20 years old. I lost him when I was 51. We packed a lot into those 30-plus years. Just not enough. It would have never been enough. Saying goodbye, though painful, was a gift. His celebration of life brought out two men I knew at a crucial point—at the same point, roughly, that I met Jon—when I was a youngster who needed some direction and role models in a career I'd chosen but didn't quite know how to get myself into. In 1990 and 1991, I was working as an agate* clerk in the sports department of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Jon, just out of grad school, was an editor on the sports desk, particularly gifted at page design, the discipline I fancied for myself and yet had never really done**. Frank Christlieb was a copy editor on that desk. Steve Waggoner was a copy editor and layout man. All three of them were heroes to me, along with an entire crew I can still mostly name, all these years later. Hille and Ed and Darrell and Dano and Doug (RIP) and Bullet and Sven and Lisa and Susan and Joe Mac and Joe and Coach and Tod (also RIP) and Brian (yet another RIP) and even my stepfather, Charles Clines, though we never made much of our connection while at work; we were too circumspect for that. So, there I am, Saturday afternoon, waiting outside the venue where we're to say our goodbyes to Jon (dammit, I still cannot believe it), and Frank is the first one I see. It's been upward of 30 years since we've lain eyes on each other, but thanks to social media, it's instant recognition and a hug. Waggoner comes, too, and it's the same thing. Thirty years gone, but time, for a few moments anyway, has stood still and let us greet each other. Ana, his wife, same thing. She was there all those years ago at the Star-Telegram, and she was there Saturday, and it was nothing short of wonderful to see all of them. And it was the next day, on the first leg of a two-session drive home to Montana, that I realized how Jon had blessed me with another gift. I got to hang out with those folks, to hear their stories and to tell mine, and maybe to impart in some way how much I was affected by being around them when I was a little pissant editorial scrub. Not because they condescended to me (they did not) or because they were especially nurturing (they sometimes were, but they had jobs to do that didn't involve nursing me along), but because they provided an example: Here's how the work is done, here's how you take it seriously, here's the difference between being diligent and being lazy, and here's what it looks like when you've done well. I carried that stuff with me to other states and other newspapers and other jobs***, right up until 2013, when I left the print business. I hucked those lessons onto my shoulders when I resumed my career as a journalist****. I was lucky, indeed, to have such role models at such an age. And we were all lucky to have a friend like Jon. As for the celebration of life itself, it was bittersweet, as such things tend to be. Jon was well loved by many, and they came out to toast him. Elisa has a really nice remembrance of him at her blog. You should read that. I gave one of the eulogies, which I'll mostly leave to the air that carried it, but there's one part, at the end, that I need to remember for the next loss that takes me to my knees. You live long enough, and they come:

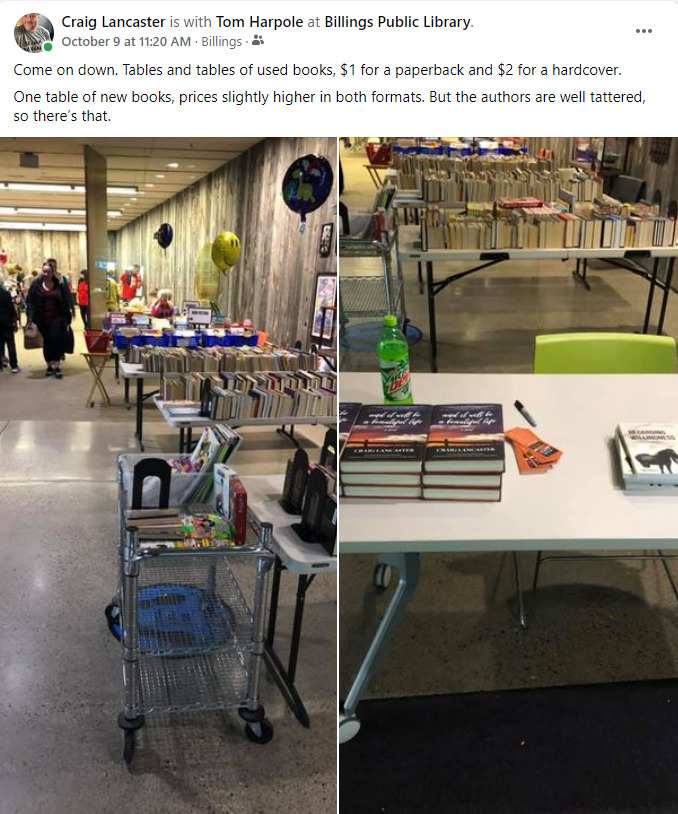

I could rage against the fates that took him so young—when he had a son to see deeper into life, and a wife who loves him so and with whom he made common cause, and birds to tend to, and veterans to honor, and talents yet to be mined and developed, and chicken wings yet to debone. And yet, I don’t. I’m not angry at the universe for calling him back to stardust, no matter how unfair the timing might seem. How could I be angry, when it’s the universe that gave him to us in the first place? He is my brother. He has been that since the first day he and I looked at each other and mutually acknowledged, yeah, OK, I’ll take a few spins with this wacky bastard. That was our call, our decision, and the vagaries of life and loss have no say in it. Jon's still here. He's not accessible in the way that I would prefer, but he's with us. And we are with him. Always. End notes * — Agate, dears, is the small type you see in newspaper box scores and the like. At a major metro paper like the Star-Telegram in the early '90s, it was a full-time job to compile agate, set it, take call-ins over the phone, make a dinner run for the editors, etc. ** — I ended up winning some nice page design awards in my newspaper career, and I've done the design work on an esteemed quarterly magazine for nine years now. It's nice when aspiration meets opportunity. *** — I went into all that in a Substack post. **** — See this. 1/5/2022 2 Comments Done ... And Barely StartedHello, 2022 ... and all of you here to see it. It's been a trip, huh? Just before Christmas, in a final furious week of drafting, I finished the first pass at a new novel, which I'm calling Dreaming Northward. It is, as I expected given the brisk pace of my finishing kick, both a fully satisfying arc and a manuscript that needs a lot (A LOT) of work. That's how these things go, at least for me. I write them to see I can get from here to there, then I spend a lot of time cogitating on what I've done, then I rewrite to more fully expose the story I think I'm trying to tell, then I revise, revise, revise to really hone whatever it is that I have. (Followed, of course, by even more editing if—knock wood—the thing gets published, followed then by a beautiful, finished book that I immediately wish I could have another crack at.) Anyway, I hope to share it with you ... sometime. Probably 2023. We'll see. A lot left to do. I mention this because my friend Jeff Deck reminded me of something on Facebook today. Here are Jeff's words, which are much more eloquent than mine: I'm Random Penguin House author Jeff Deck, and I have an important message for you today: Getting published by a major house will not make you rich. It will not pay your mortgage. It will not clear up your skin. It will not get rid of those love handles. It will not make you a bunch of friends, nor will it get you laid. It will not make your distant parent say they're proud of you. It won't relieve you of the onus (and cost) of marketing your book yourself, either. What it will do is get your book into physical bookstores. And potentially improve your chances of getting a second book traditionally published. But mostly it's the distribution thing. Many people fix their eye — and their hopes, and their self-validation — on getting published by a major house. My wish for you is to recognize the value in your work no matter how it ends up being published, whether via the Big Five (Big Four?), a mid-size or small press, or self-publishing. Recognize the value in it BEFORE it's published, too. The work you put into your story is real. The time you spent improving your own skills along the way should be recognized, and celebrated. Goals are important for motivation. But you are "worthy" *right now*. And you will continue to be worthy every step of the way. Writing is a long journey, even (especially) after publication. No matter which publishing route you choose. Belief in your own value — and a daily celebration of your own work and words — will sustain you along the way. Every word is absolutely true, by the way. I often tell folks that they should celebrate having done the work as much as they celebrate anything that flows from that work. Sometimes, they think I'm bullshitting them. I'm not. The work is sustaining. The rest is ... the rest.  The rest Received some lovely news yesterday. And It Will Be a Beautiful Life was the bestselling book for 2021 at my local independent bookstore, This House of Books. I'm grateful to the bookstore—where I'm a proud member-owner (it's a co-op)—for being such a wonderful supporter of not just my work but of the many, many fine regional writers who are doing such important work here. And I'm grateful to the folks, near and far, who bought a copy from THoB and kept the oxygen flowing to an independent bookstore. The cultural life in my town is much the richer for its presence. If you'd like a signed copy of the book, THoB will be happy to fulfill that desire. Simply order online and mention in the comment field that you'd like it signed, and I'll hop into my trusty blue Toyota, drive downtown and sign it for you. And, hey, if it's a paperback you want, I have good news: The paperback version releases in May, and you can preorder through THoB (I'll be happy to sign those, too, once they come in), through your local independent bookseller (please!) or wherever you get books. 10/13/2021 1 Comment Social ... and Socially DestructiveFirst thing: I'd be gratified if you'd go to this link, where my wife, Elisa Lorello, keeps her newsletter. She's written eloquently and emotionally this week about her pullback from social media: why she did it in the first place, ways in which she has come back, and why she'll never return to what her presence used to be. She gets at a lot of the things I've wrestled with, and she's been far stronger than I have as far as making some of her resolutions stick. If you like what you read there, you might consider going to her website and signing up for the weekly (sort of, kind of) dispatch. A little Elisa in your in-box is a day brightener, and we all need those. The truth is, we've been grappling with social media and its impacts on us, on how we congregate and communion and deal with each other, for as long as we've been becoming friends with Tom and booking staterooms on the S.S. Zuckerberg. It's just that the more pernicious aspects of an online life have been slower to come to us, and by the time they do, we're already addicted to the cat pictures and the easy reconnection with high school friends and the ready microphone for whatever is on our minds. (On mine, mostly: breakfast.) Every time I'm about ready to declare social media, on the whole, a net negative, I can feel a "yeah, but" bubbling to the surface. Over the weekend, I shared a table with Tom Harpole (author of Regarding Willingness, a great book you should read posthaste) at a library book sale, and we had a humdinger of a time building a genuine human rapport out of a friendship that had, to that point, been nurtured entirely online. So, if I'm ready to bag social media—and I am, baby, I am—am I also ready to foreclose the possibility of future Harpolian friendships? Um ... What about the genuine, deep love I've come to feel for people from my hometown I didn't know that well the first time around (I went to a big-block-store of a high school, so it was mathematically impossible to do it any other way)? What about the book club in Virginia who'd all be my besties if we lived closer? What about a dozen other examples I could rattle off without even contemplating it? I think the greatest disappointment of social media, for me, is that I thought (naively) it would be a tool of greater connection and empathy, and in its worst iterations, it's been precisely the opposite. I cringe when I look back on something like this interview, in which I extolled the virtues. They're so much harder to see now. And look, I don't think the problem is the technology, per se. We've leveraged new tools in our communication since human history began, from grunts to cave wall drawings in ochre, from plumes to pencils to printing presses to pixels, from phones that share party lines to phones with long-distance tolls to phones that aren't even used, primarily, as talking devices. But connection was the point, right? And now, in ugly and pervasive ways, the point is division. Harp said something while we were together, a grand occasion that I think will leave us demanding more like it to keep oxygen flowing in the friendship, and I haven't been able to shake it since: "The world is getting to a place where an empathetic person will find it impossible to live here." (I hope that's near enough to a direct quote. I wasn't taking notes, just reveling in the fellowship.) I think that's it, in large measure. Empathy is lifeblood for me. I can't imagine getting through my days without it. I can't imagine living in a way that I don't strive for it. I can't imagine wanting to be here without it. I'm going to try to live where kindness lives, to plant it where I am and where I'm headed. I'll fail sometimes, of course. That's part of the human bargain. But that ideal has to be the north star, or what are we doing here? (And, yeah, I get the irony of having pounded this out on a website, the link to which I'll distribute on Facebook and Twitter. We're hardwired for hypocrisy.* All of us.) (* — Credit to the great Barry Eisler for highlighting the Niebuhr passage.) Quick programming noteNovelist Jamie Harrison and I are doing this online conversation, hosted by the Montana Book Festival, about fiction and families. I think it's going to be a lot of fun with some interesting insights, and if you have some time Saturday (Oct. 16), I'd be well pleased if you joined us. The event is free, but you have to register here to get a spot.

|

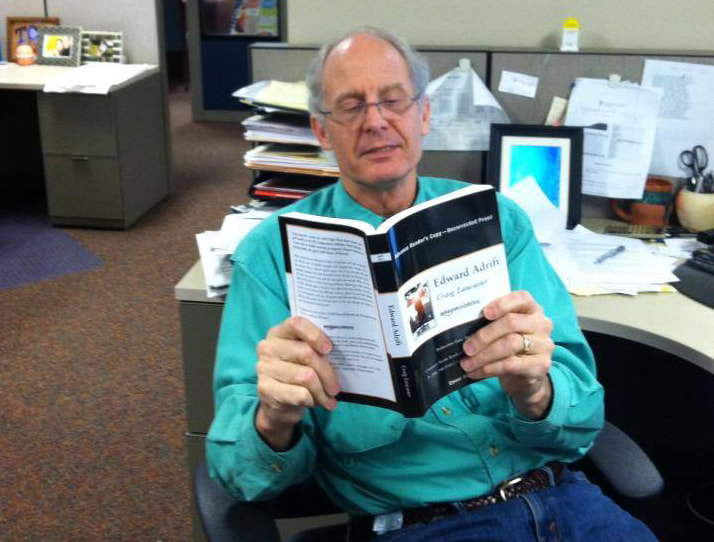

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed