|

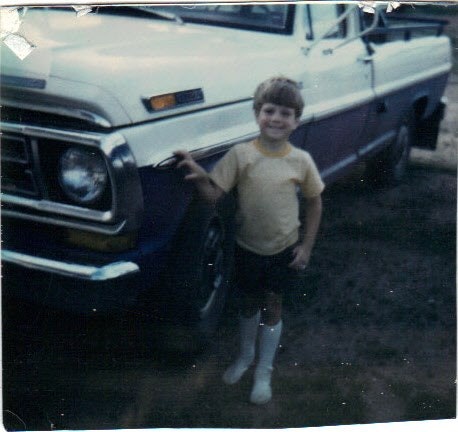

9/24/2021 5 Comments Back to the Fork in the RoadIt's Sunday, September 19, and I'm on Interstate 25 in Casper, the nose of my car pointed north, toward home, a few hours away. I'm tired. My dog, Fretless, lies languidly in the passenger seat. He's had enough after a week away. So have I. Home, my wife, the cat—they all await. We have plenty of gas, had a bite to eat back in Douglas, fifty miles behind us. We have everything we need. The smart play is to get beyond this oil town and open up the cruise control a bit, see what this Toyota can do as we zip back into the emptiness of Wyoming and, eventually, get pulled into the embrace of Montana. So, of course, I exit the interstate, pick my way through downtown Casper, find CY Avenue—I once called it, in a novel, "the spine of the Casper grid system," which may or may not be true—and follow its familiar path to where I turn off for Mills, a little town north of Casper, and as I do, the well-trod memories come at me again. What I've come to see has been seen before, many times, and is likely to be seen many times yet, and if this particular side trip is taken as evidence that my life is in reruns, I will say only this in disputing that notion: Context is important, in all things and especially in this: I find it instructive, or at least perspective-granting, to be reminded of the life I might have had so I can better appreciate the one I'm swimming through. It's Friday, September 24, the day I'm writing this, and I'm reflecting on a spontaneous turn in a phone conversation with my mother this morning as we talked about other things. We talked, quite organically, about a decision she made for both of us in 1973, my third year. I was a capable kid, even at that age, blessed with an ability to carry on conversations with adults, but this matter was beyond my perception. She didn't want to live in Mills, Wyoming, anymore. That was surely half of it. The other half was that she didn't want me to live in Mills, Wyoming, anymore. She looked at the present, our life with my father there and what it seemingly held for us, and she projected out her future and mine and didn't like where those lives seemed likely to end up, and she did something about it. She took us out of there, into life with a man she'd met that year, the brother of her best friend, a man who lived in Euless, Texas. Not that it's anyone's business, but they hadn't had an affair. They'd had a connection, a chance meeting at a party that turned into a deep conversation that blossomed into a friendship and has become a nearly 48-year marriage. We talked about it this morning, Mom and I, this decision that with each passing year strikes me as more and more brave, more and more essential to both of us (and now to so many others—generations of others), more and more the line of demarcation, in strictly selfish terms for me, between where my life was pointed and where it ended up. I can see now, when I'm more than two decades older than she was then, how much gumption it required for her to do what she did. She was alone there, much of the time. She was 28 years old, and while Dad might not have represented maturity or loving or grace (I love the man, but let's be honest about the limitations), our prospects there were much more certain than they were anywhere else. There was a home well on its way to being paid off, an ascendant business, money in the bank. It would have been all too easy to stay. Many people have stayed for less. Mom saw the future and she left. I'll never receive a finer gift. So, you see, Mills, Wyoming, is actually a bit player in this what-might-have-been contemplation. It wasn't Mills we were escaping so much as who was there and what our life was there. It could have happened in Moline or Schenectady or Topeka. Could have, but didn't. This is, at its heart, a human story, a story of a boy with three parents who've imprinted him in wildly varying ways. I love my father, a love that shines through my struggles to understand him and his to understand me. It's a love strong enough to withstand my suspicion that my start in life would have been less than it was had I finished my growing-up years in his house. The math of that situation is inconceivable to me, given the way it all went. It would have been Mom and me in some kind of alignment agaInst the gravity of the way he is, the work that was always taking him away from us, and the instability of the home we were living in. I'm certain Mom's decision all those years ago hurt him. I'm also certain, if Dad can access clarity and honesty, that he'd say it needed to happen. For all of us. And what can a boy like me say about his mother that hasn't been said in better ways by better thinkers? She is pure love when it comes to her children and her children's children, but to leave it at that misses the fullness of who she is. At an age that seems to me, now, to be impossibly young, she was relentlessly wise. She had aspirations for herself (and has them still). To my ongoing gratitude, she could see a time coming when her son would have them, too. In so doing, she brought me into the sphere of the man who became my stepfather. Back then, he was a 31-year-old sportswriter at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, a man who had his own broken first marriage, a son, and regrets. He also had a shared hope with Mom that they could make a go of it together. I can scarcely remember a time before his presence in my life, and he has never, not once, treated me as anything but his own. That has made all the difference. I go back to Mills to remind myself that it could all have gone another way. Could have, but didn't. So what do I make of Mills, all these years later?

I think it would be presumptuous of me to make anything of it beyond my sliver of experience there. It's steeped in nostalgia and memories and wonder. Its presence on the outskirts of my life has been a professional gift, surely (the old memory + imagination thing), as well as fodder for the occasional facile joke. (One could certainly quip about "welcome to Mills, please set your watch back 20 years" or wax irreverent about how hard the wind blows there.) The thing is, I've lived enough places and known enough people to realize something important: Most anyplace can be home, depending on who's doing the inhabiting and what they bring to it. I suspect—but don't know for certain—that my life would have harder and less interesting had I grown up in Mills. It's the not knowing, of course, that makes it such a delicious ponderable. So I go back, and I look around, and I try to imagine who that boy might have been, what kind of man he might have become, where he might have gone and what he might have seen. And because Mom imagined something else entirely, way back in 1973, I can be ever grateful for the real story that lies alongside the conjecture.

5 Comments

My friend Caroline Patterson has a new novel coming out Sept. 15. It's titled The Stone Sister, and it promises to be an absorbing, fascinating read. It's getting some fantastic endorsements from the likes of Ann Patchett, Annick Smith, and Kim Zupan. Here's a book trailer: Looks fascinating, doesn't it? Well, go get it.

And while you're at it, be sure to check out Caroline's exquisite new website and learn more about her and her work. 8/23/2021 15 Comments Jon Ehret, My BrotherNot that we’re back in eighth grade or anything, but in the couple of days that this thing has been sitting on my head, wanting to come out through my fingertips even as I had no idea how I would start it or where I would end it or what I would put in the middle of it—and, Jesus, now I’m quoting Seger, what to leave in, what to leave out—I’ve been thinking about a decidedly eighth-grade question: Who’s your best friend? Seriously, who? Is it your spouse, the person you spend the most time with, the person who hears and tolerates and rides out all the stupid shit you say, the person who’s in bed with you, who knows every embarrassing thing, who shares all the same things with you, who knows where the hurts and the hopes and the hesitations are? That would be a good answer, your spouse. In most considerations, yes, that’s absolutely the answer for me. Or is it your work confidant? Your childhood friend who has somehow endured? The high school classmate you didn’t know then but are connected with now and cannot imagine not knowing and loving? Your college roomie? Is it your neighbor, the person in the pew every Sunday at church, the father of your kid’s best friend? Or, maybe, is it someone who has rippled through your life, like a pebble sending slow-moving water rings to the shore? You had something going for a while, then life and distance intervened, then you picked it up and it was just as good as before—no, no, it was better—and then you set it down again, and then it came back one more time and it stuck for good. It has survived decades and losses and different cities and different sensibilities and different marriages and different jobs, and it’s the same thing it always was and it’s also something new, something evolving, something surprising and cherished. Couldn’t the person with whom you share all that be your best friend? Shouldn’t the person with whom you share all that be your best friend? Jon Ehret was my best friend. Jon Ehret is gone. How am I supposed to do this without him? Before I get into the various specific times and qualities and shared experiences that made Jon my friend, I need to answer broadly the question of why it worked for us, why we latched onto this friendship in the last decade of the previous century and saw it through for thirty years. No offense intended, but I don’t need to answer that question for you. The world can go on spinning if you don’t understand it, and while the world certainly will go on spinning if I don’t answer for me, here’s the deal: In hindsight, I can see it, all of it, what we shared and why it mattered and why it stuck. And hindsight is all I have, now. The drive Elisa and I never made to see him and Laura in their new house in Santa Fe, that’s not happening. His invitation for me to head down and meet him in Utah, where he was picking up a rescue bird (there will be more on this), the one I turned aside with “damn, my work schedule” and “invite me on the next one”—there won’t be a next one, and thus there will be no invitation. The last time I was in Buffalo, N.Y., his hometown (there will certainly be more on this), and invited him to fly out and he turned me aside with “damn, I’ll be at a wedding in Texas.” Yeah, that’s not happening, either. It’s all hindsight and memories and smart-ass ripostes on Facebook and a text thread on my phone that I will never erase, in hopes that I can someday bear to look at it again. That’s all there is. So here’s why it happened and why it mattered and why it stuck, and if this is too abstract, you’ll just have to trust me: Jon and I were the same but different, and this is the second time in a week I’ve used those words to describe the way I’m hard-bonded to someone. And because those bonds were so difficult for each of us to find with other people—there’s nothing like the unexpected death of your best friend to serve as a reminder that you make friends broadly but struggle to hold on to them deeply—we held tight to the fact that we found them with each other. I think we always knew what it was, but we took a long time to acknowledge it with a nod and longer still to say it and put wind under the words. We did, though. For that, I’m grateful. I have that, too, and so does he, wherever he’s off to. So, look, I should hope it doesn’t happen to you, but maybe it already has, and the longer you live, the greater the likelihood that it someday will. Your phone rings one bright day, and it’s Laura, and you know it when you hear her voice, because although you’ve known her for as long as you’ve known him, and you love her as much as you love him, he’s still the conduit by which the whole thing goes, and if she’s calling, that must mean Jon cannot, and so here it comes. This all occurs to you in a whisper of a fraction of a second. It’s fucking insane how fast and final it all is. Jon died at work, at the bird rescue center in New Mexico where he had found purpose in semi-retirement. He was in his joy, and then he was gone before his coworkers found him. Fifty-five years old. Heart attack, it would seem. No warning, no chance at intervention and another outcome. Gone. I spent the better part of a decade flat-out ignoring a condition that I knew would kill me if I let it. Jon had a lovely day with his wife, then went off to his birds, and never came home. We’re the same but different. Laura tells you all this, and you remember another phone call, 1993, Owensboro, Kentucky, to Buffalo, New York, and you were the one piercing the bright day and saying our friend, Brian, he’s dead, and Jon says, “Why?” And you realize that’s one hell of a good question, then and now, because it’s the only question you have: Why? Nobody fucking knows why. And you bounce to another memory, Brian and Jon at the center of it, where you’re at work as a sports clerk at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, couldn’t have been later than fall of 1991, and you’re making fun of your boss’ phone manner, because you’re 21 and a smartass, and you pick up a dead phone and say, “Staaaaar-TelegramsportsthisisEd,” because that’s how Ed says it, and all the editors on the desk are laughing, because you’re one funny sumbitch, and you don’t see Ed behind you and he says, “That’s pretty good. Good skill for your next job.” And here’s Brian: “I just got a warm feeling.” And here’s Jon: “That’s not a warm feeling. That’s Lancaster pissing himself.” And here you are, missing them. We met at the Star-Telegram. Jon was 24, and I was 20. He had a master’s degree from the University of Missouri in hand, and I was steadily on my way to bombing out of college for good. The same but different. He liked The Who and King Crimson. I liked Paul McCartney and R.E.M. I was making plans to move to Alaska (for the first time), and he thought that was the coolest thing in the world. I thought he was the smartest guy I knew, a brilliant layout man (we drew them in those days, kids) and someone worthy of emulation. We were big, lumbering guys, often more comfortable in our interior lives than we were on the outside. I covered up with a sort of zany bearing and kept a lot of my deeper thoughts to myself. Jon balanced anger and the most generous heart I've ever known. The same but different. Later, the connections went deeper. A weekend with the Ehrets after he and Laura moved to Buffalo, a day trip to Niagara Falls, an introduction to Newcastle Brown Ale, before it went all corporate. A snowy night, the last of the trip, when we ordered in and he urged me to get a cheeseburger sub and when I hesitated, he was all, “Man, it’s a cheeseburger on better bread. What’s the problem?” No problem at all. Delicious. And while we had surely eaten meals together before then, in my memories that’s the line of demarcation where shared food experiences became part of the deal: Jak’s in West Seattle, barbecue in Texas, seafood in Damariscotta, a legendary birthday meal at Walkers here in Billings on a minus-12-degree day, his urging me toward Ted’s Hot Dogs and Duff's in Buffalo, and my going to both, every time I'm there, even though we were never again there together, now much to my eternal regret. “Buffalo is a great fatboy town.” I say it. I live it. Jon said it first. In 1996, I decided, after some consideration, to seek out my birthmother. I told Jon what I was doing, because I knew Jon would have both an appreciation and a point of view, as an adoptee himself. He didn’t tell me not to, but he presented every you-oughtta-be-careful-here he could think of. He said he couldn’t imagine doing it. I did it anyway. Many years later, when he could imagine such a thing, I could give him some on-the-ground intel. I could validate the things he got right, contradict the ones he got wrong, and throw up flags around the ones neither of us thought of. He did it anyway. And, our being the same but different, we had more to talk about, in conversations that had the width and breadth and depth of galaxies. The kind we had so much difficulty having with other people and yet never had trouble getting into together. Another night of spotty sleep draws near, so let me just wrap it up this way:

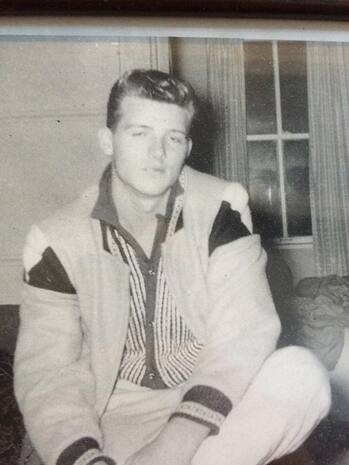

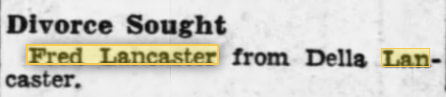

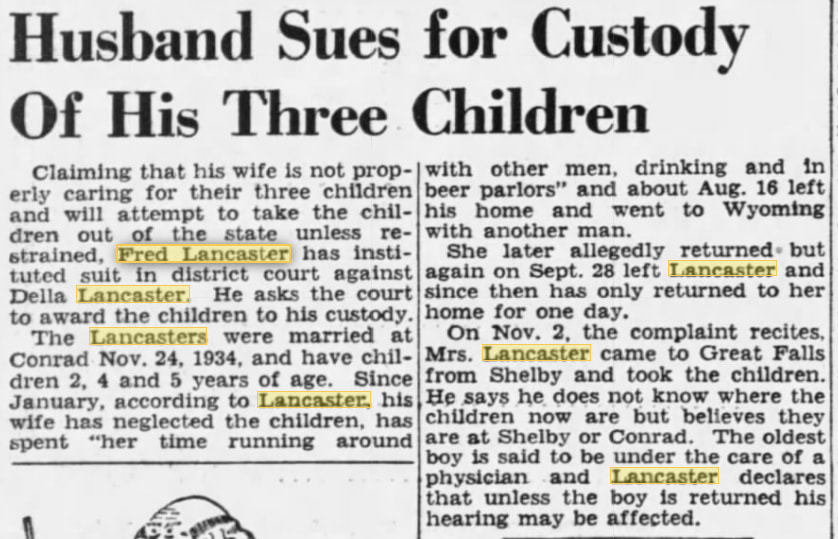

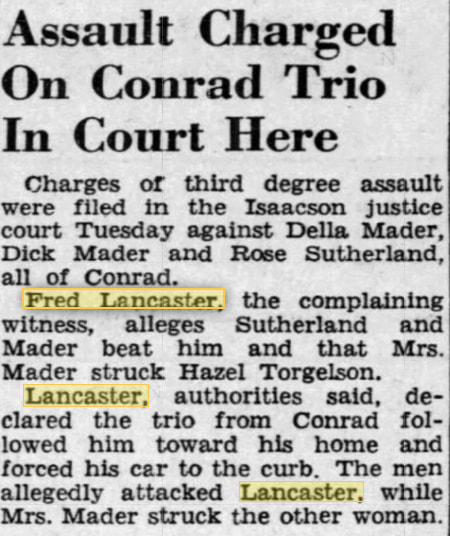

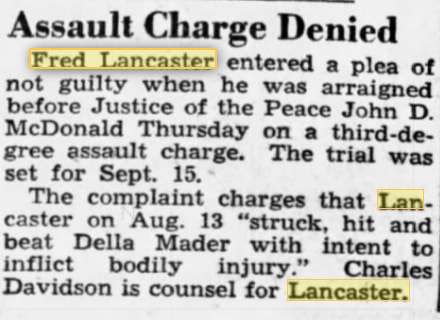

I have four brothers in a family line that looks like a tangle of kudzu more than it does a tree. There’s the brother I inherited when my mother and my stepfather got together. We lost him four years ago. There’s another who was born to that union. And there are two half-brothers who came with the search for my birthmother, the one I pressed forward with despite Jon’s admonitions, just as he pressed forward later with his own quest and his own questions. Neither of us, I think, would turn aside the decision we made after it was done. The same but different. Then there’s the fifth brother, the one I chose, and the one who chose me. I know he’s my brother because he told me so, and because I told him so, and because he was the kind of guy who didn’t use words he didn’t intend, and he told me these a long time ago: If you ever need anything at all, you tell me, OK? I took him up on it, too, in ways that seemed picayune at the time and register even more inconsequentially now. I was lucky, I guess. I never needed anything substantial and life-changing. A kidney. A roof over my head. A slayer of the wolves at the door. You know, the biggies. A heart. He filled mine. He broke it, too, just the other day. I’ll patch it up. He lives there now. 7/13/2021 0 Comments Down the Rabbit Hole …... and into the rest of the story, or at least more of it. I've been on the masthead of Montana Quarterly for the better part of a decade now. But back in 2010, when I had one novel to my name and not much else in the way of published literary work, I was just a guy pitching an essay to Megan Regnerus, then the magazine's editor and now our beloved editor emeritus. I called it The Small Things, and it was written after my father, Ron, and my Uncle Bob Witte (RIP) ventured out to the Fairfield Bench, near Great Falls, and found the dairy farm that shaped Dad's young life in some pretty horrible ways. I won't say much else here; you can read the piece for yourself, and I hope you will, because it provides a good anchoring for some discoveries I recently made while digging through archives. Long story short: I've always wondered about some of the details my father told me that day on the bench, not because I thought him dishonest about the general gist of things, but because he was 71 years old (he's 82 now), and that's a lot of time for the finer points to get lost. But he hadn't lost them. Not really. Let's dig in ... From the piece: "I’d heard, or maybe I’d assumed, that my paternal grandfather, Fred, had walked out on the family when Dad was two or three years old. But here was Bob, telling me that it had been a proper divorce and that Dad’s mother had rejected the children." The archives say ... Pretty much dead-on, if Fred's account of it is to be believed. He sought the divorce. He also tried to get the children (Dad, his older brother Duaine, his older sister Dolores). From the piece: "When Fred showed up to get Dad a week later, Dick locked the little boy in the basement and met Fred at the road. He carried a shotgun, all the better to send Fred on his way. Three children could accomplish a hell of a lot more work than two, and Dick aimed to keep Dad close, be it with a gun or a fist or a horse whip." The archives say ... Nothing I found speaks directly to this episode. Still, I'm not about to contradict Dad; he remembers it, he's shaken by it all these years later, and trauma has a way of imprinting itself immutably. What I know for sure is that Fred and Della and the man who became her new husband, Richard Mader, had confrontations. Here's the evidence: I've saved the best one for last. The remembrance of my father that was shrouded in the most mystery was where he went and what he did when he finally ran away from Richard Mader's dairy farm for good. Dad's memory is that he went to work for a farming family near Three Forks. I had no reason to disbelieve him, of course, but Three Forks is a fair distance from Fairfield. I wondered how he got there and whether he might have actually ended up somewhere else, somewhere closer, and just lost the place to the intervening years. Nope. From the piece: "After a few weeks, he ended up on a farm in Three Forks, doing odd jobs and being attended to by a kind family that kept him shielded from Dick, who was still looking for him. After a year or two, Dad told the farmer that he would like to see his father again, and the man agreed to find Fred and take Dad to him. A few weeks later, word came: Fred was in Butte. "More than fifty years later, Dad’s voice broke and his eyes floated in tears as he revealed what happened next. They were the only emotions he betrayed in telling the story. “'The farmer told me, "I’ll drive you to Butte and once you’re there, I’ll put you in a cab and follow you to your father’s house. Once I see that he’s come out to get you, I’m gone." ' "In a singular act, that Three Forks farmer, whose name has been lost to the intervening years, did for Dad what no one else could be troubled to do: He acted in the best interest of the child." The archives say ... Well, just have a look from a newspaper's "persons sought" column:  Dad, early 1960s. Dad, early 1960s. Getting at the details of my father's life has been a driving pursuit for many of my own days. Part of it is that I'm his only child, and if there's a story to be salvaged, it's up to me to mine it and tell it. And part of it is that I'm so heartbroken for the boy he once was, a clearly smart youngster who was denied so many of the blessings of his age, who was brutalized and stunted and who has persevered despite it all. I know how violence cycles from generation to generation, and I also know that the man I call Dad has refused to spin it on into me. It's the great achievement of his life, and he probably doesn't even know it. I want to drag the shit that happened to him into the light, the best disinfectant for what was visited upon him. He's not a hero. He is, in fact, a deeply flawed man (as is his son, as was his own father—there's more to that story, for another time). But he's my dad, and I love him. Addendum: There's an earlier piece, originally published by the San Jose Mercury News in 2004, that focuses more on finding out what became of Fred after Dad reunited with him in the mid-1950s. That was the last time father and son saw each other. Dad went into the Navy, and Fred went ... well, that's the interesting thing. You can read about that here. 6/11/2021 0 Comments How to Spend a Day in Montana** — one of an endless number of permutations 9:50 a.m.: Head out of Billings due west with fair Elisa. Destination: Livingston, 117 miles down Interstate 90. There is much I could say about Livingston, although it would be nothing that hasn't been said before by better observers with keener insights. I made a friend laugh earlier today by calling it my Emergency Backup Montana Hometown. That's how I feel about it and the people I encounter there. (It was good to see you, Marc Beaudin. It's always good to see you.) 11:45 a.m.: Meet Kris King for lunch at Neptune's. In my early days of designing Montana Quarterly, Kris—one of the magazine's steady contributors (she does the author interview each issue)—gave me shelter on my overnights to Livingston for final magazine production. She's a whip-smart, offbeat, fun, funny, wonderful friend who has been extraordinarily kind to us, and it was the first time we'd seen her in more than three years. (We moved to Maine. We moved back. There was/is a pandemic.) If you've read my short story Remember Me in Istanbul, you might remember the ex-girlfriend's house that a guy and his wife let themselves into on a winter night. I modeled that house, and the spirit within it, on Kris' place. Now you know ... Around 12:40 p.m.: Head a few blocks over and get a sneak preview of the forthcoming Edd Enders Retrospective. (June 18-19 in Livingston, and you should totally go if you're within driving distance.) It's one magical thing to be able to stare deeply into a single Enders work, which we're fortunately able to do every morning, as one adorns our bedroom wall. (I mentioned Kris King and her kindnesses; the painting below is one, a wedding gift that we treasure.) It's quite another to see canvas upon canvas, crossing all eras of his wonderful work. What a thrill for us. Around 1:15 p.m.: Head out for Bozeman, another 26 miles west. We ended up at the Emerson Center, a place I'd often heard about but never visited. There, I dropped off a copy of And It Will Be a Beautiful Life to Rachel Hergett, one of Montana's premier writers about the arts. It was our first face-to-face meeting, another unfortunate byproduct of the pandemic. Can't wait to renew acquaintances again and again. I'm telling you, there was a buoyancy to the entire day in this regard. We're opening up, and hope is flooding in where darkness once settled. I'm allowing myself to dream of literary readings and concerts and sporting events and dinners with friends. Around 2:45 p.m.: Two more stops, both essential. First, Country Bookshelf, one of the finest bookstores you'll find anywhere. What a wonderful feeling to see the new book paired up in the window with Sweeney on the Rocks by Allen Morris Jones. Allen and I are doing a virtual event hosted by Country Bookshelf on June 30. We'd love to see you. And then to also see it on the shelves ... I also scored a Gwen Florio novel. Signed. Who's the lucky kid? Finally, no trip to Bozeman is complete without a stop at The Baxter and the little chocolate shop in the lobby, La Châtelaine. Elisa had the Hawaiian red salt caramel truffle. I had the French martini truffle (below). We split a Meyer lemon truffle. No regrets! After that? Eh, there's not much to report. Just a 143-mile drive through some of the most beautiful countryside there is, pulled along by the mighty, north-flowing Yellowstone River, a ribbon to guide us home. In the best iteration of myself, I try to be grateful for the life I have and the way I'm able to live it, but circumstance and the intrusion of transient difficulties sometimes get in the way. Perfectly natural, of course, but also something that can swallow your perspective if you let it.

Today was all gratitude all the time. For this life, for this place, for these friends, for these adventures, for the next bend in the highway ... 6/10/2021 0 Comments Some Distances Defy BridgesOriginally published March 11, 2021

My father and I were on our way to a vaccination clinic several weeks ago (1), which should have been a happy occasion, and yet tension and sharp words edged into matters, as they so often do. The clinic was close to both my house and the vet from which I’d ordered Dad’s allergy-ridden dog some food, so I laid out the plan: get our shots, drop my wife off at the house, go get his dog’s food, take him home. It should have been an unassailable itinerary but wasn’t. “Just take me home,” Dad said. “That way, you don’t have to run back and forth.” “No,” I said. “It’s a loop. And if I take you home, I’ve still gotta come back home, and you don’t get your dog food.” “I don’t need it today.” “But we’re almost there.” “OK, OK, Jesus.” And this, of course, is when my anger burned and, because I am not smart enough to hold my tongue, I let him have it: “You know, I actually have a brain, and I can actually use that brain to figure shit out.” Boom. Silence, the rest of the time we were together (2). I don’t want to hang too much on this one flare-up, except that it’s representative of almost every flare-up that ever preceded it and predictive of every conflagration yet to come. We’re two stubborn men who share a last name—but no blood (3)—and almost nothing else, except some deep-seated compulsion to love each other despite it all and to keep trying to hold together a relationship. I suppose, by that metric, we’ve done reasonably well. We’re fifty-one years in, and neither of us has cut the other loose. We’ve flirted with short-circuiting the thing a time or two, but we’ve never had a rupture we couldn’t eventually pick our way across. I’ve had the better part of my lifetime and his (4) to consider what the fundamental difference between us is, and while the flippant answer--everything—remains ever at the ready, I think the heart of it comes down to one basic thing. Reflection. That is, the essential quality of looking within to discover why you are the way you are, what experiences shaped you, how those experiences were viewed at the time and are viewed in hindsight, how they might inform the choices at the junctures yet unseen. Reflection is the currency by which I get through the world. A lot of what comes up into my face doesn’t make a lot of sense to me in the moment, particularly if I’m trying to suss out someone else’s angles or motivations. I’ve learned to trust hindsight and time to bring clarity to at least some of what initially seems inscrutable. Where I’m able, and when I sense that I won’t do more damage, I’m a big believer in closure, even if the loop that gets tied off rests solely within my own head. My momma taught me two things that have been invaluable to the flawed man I’ve grown into: I can say I’m wrong when it’s so, and I can say I’m sorry and mean it. My father has never shown me either of those two capabilities, and if he’s inclined toward reflection, he keeps those thoughts awfully close. They never travel from his head to his mouth, and thus they are at least twice removed from the ears of someone who could stand to hear them, someone who might reconsider much if he could get some help in understanding just a little. Here’s where our key difference, the factor at the root of every occasion when we get at loggerheads, tangles me up: Am I exercising a form of privilege when I put such value on reflection? My life is not like his. Nobody hassles me if I take the time to linger in my interior life (in fact, I could well argue that it’s a professional imperative). Dad’s growing up was fraught and dangerous, and it’s entirely possible that he doesn’t look behind him because so there’s so little back there he would want to see again. When I’m at my most frustrated with him, when he’s been withering in his criticism or his disdain, my wife often steps in to remind me: His whole life has been about survival. He doesn’t think about how the moments connect. He thinks about living to the next one, then the next one, then the next one. You can see it in his pantry, stocked to survive a nuclear winter, even though he eats like a bird these days. He keeps the wanting at bay. Do I have an obligation, then, to take him as I find him, to give him a pass for all that he is and all that he might well be incapable of being, and to do the heavy lifting required to meet him where he stands? Maybe. Then again, I could make a good case that I already do, and that whatever distances remain will be closed only by an equal effort from him. I’m his ride to where he needs to go. I’m his paperwork processor, the one who makes phone calls on his behalf, the reader of fine print, the sentry against scammers, the negotiator of byzantine governments and health care providers. I’m not a martyr to these things; they’re just duties I’ve picked up along the way, as first he aged and then he became elderly, as eyesight and health slowly fail him without robbing him, yet, of time altogether. I have one goal for him—a singular hope—and that’s to see him into the cosmos without pain or terror. And the scariest part of that duty is the possibility that my own health might falter before I can get him there. So we go on, he and I, to the next obligation, the next game of backgammon, the next time I’m utterly unable to explain to him who I am, what I value, where my aspirations lie, what I’ve learned along the way, and where I keep failing. Until the next time we bark at each other, then sift out the silence, then pick it up and try again. By the time you read this, our second shots will have been administered. He’s no doubt forgotten the last time we butted heads. Me? I’ve turned the memory into the hope that there won’t be a next time, or that I’ll find it within me to be a better man should it come. I wouldn’t lay favorable odds on either one. Endnotes (1) And so it was that I became aware of the phenomenon known as “vaccination envy.” Three things, OK? First, I’m 1B. Second, it was my time to be in line. Third, I would trade my chronic illness—never you mind what it is, unless you’re my doctor—for a spot deeper in line. In a friggin’ heartbeat I’d make that trade. Short version: Get off my ass. Longer version: Let’s celebrate every dose. I hope yours comes soon, if it hasn’t already. (2) I’m not saying there wasn’t a benefit. (3) I was adopted at birth. (4) He’ll be 82 this summer. He had a series of heart attacks at 53 that damn near killed him. Don’t think I’m not well aware of how close I am to how young he once was. 6/10/2021 0 Comments Darrin. Originally published January 7, 2021 There’s no clever way to start this, and from the vantage point of these scant words, I feel as though there’s only one place to end it: with anger. Which sucks. Darrin Marie Murdoch is dead. As I sit writing this—on Christmas Eve, for publication in a couple of weeks—she’s been dead for four months and ten days. I’ve known for the ten days. That’s it. And I’m pissed, mostly that Darrin was plucked from this life when she was so young and so loved and so needed (which I’ll get to soon), but partly because I didn’t know she was gone until a succession of thoughts came to me: 1. I haven’t seen updates from Darrin in a while. Facebook and its confounded algorithms are hiding her from me. 2. I’ll visit her page. 3. Oh, god, no. I could castigate myself for not seeing her obituary in the newspaper or online. I could lash out at our common friends who did know she was gone and didn’t tell me. (I could do it, but I would be wrong and I would be unkind.) I blame the pandemic. Not for taking her, because that doesn’t appear to be the case. She’d had a host of health difficulties and a recent surgery, and she went to sleep one night and didn’t wake up on the other side of it. This is life and the bargain that comes with it. You gulp in that first big breath, then you start playing your time against a clock that stops at some indeterminate hour. I get all that. What I don’t get, and what I’m continually angry about in a universal sense, is why it had to be this way. Those of us who have acted responsibly (and aren’t frontline health care professionals or essential workers) have gone into our silos for nine months and counting while the government fails all of us and while we fail each other with selfishness and a miscast notion that freedom can stand independent of responsibility. Our lives have gotten smaller, if indeed we’re fortunate enough to have hung on to them at all. In the house my wife and I share, we wake up, we have breakfast, we split up for work, we reconvene periodically throughout the day, we climb into bed, and we do it all again. We have each other and our pets, and that’s a lot, but it’s also not nearly enough. Meanwhile, in the larger sense of this country’s collective COVID-19 failure, we’re all losing what binds us even as we’re inured to the loss. It feels as though, on the other side of this, we owe each other forgiveness for the things we have and haven’t said and the things both done and undone. I feel the weight of the penance I need to do, the amends I must make, and the grace I need to offer. I also feel the burden of anger that lights up and burns like flash paper. How does anyone balance all of that? In April, just a couple of weeks after we arrived back in Montana after a nearly two-year sojourn in Maine, I wrote these words for an anthology called Stop the World: Snapshots from a Pandemic. They felt visceral then. They feel something else now, in retrospect—hopeless even as the vaccines roll out (amid one final failure from the outgoing administration), sadly outdated in the death toll, and prescient in a way I never wanted to be: We’re alive, if not entirely living as we once thought of it, while we wait for something resembling normalcy to return. As I put down these words, the U.S. death toll has crossed 50,000, a number surely to rise. Only in the awful solitude of my imagination do I dare consider what it might be before these words find your eyes. I don’t want to know. But I’m going to. If I live to see the final toll. If I’m lucky. The word lucky has never been so perverse. If you’ll forgive the coldly corporate nomenclature, COVID-19 has a cost structure, and the tolls seem random: Some pay with isolation. Some pay with inconvenience. Some pay with sickness followed by recovery. Many millions have paid with their jobs. Tens of thousands, so far, have paid with their lives in the U.S. Worldwide, it’s hundreds of thousands more. The only bitterly sure thing is that we’re all paying with something. I was supposed to see Darrin again. Surely, in a normal set of circumstances, I’d have seen her between April and August. Failing that, surely, in a time unencumbered by social distancing and voluntary withdrawal, I’d have been engaged with our shared social structure enough to know she had gone. I would have been at her funeral. I would have hugged her mother, who has lost all of her children these past few years. I would have said goodbye instead of oh, god, I didn’t even know you were gone. This is part of the toll. Darrin was a teacher*. She loved those children with her whole heart. She especially loved the poorest of them, the most neglected, the ones with the biggest hurdles to overcome at the youngest ages. She believed in them, and for that reason more than any other, she should have lived forever. She was also fun, and smart, and bawdy, and loud, and loved. Every time she saw me--every time—I got a chaste kiss on the cheek. For several years, I had a standing invitation to her book club’s Christmas party, an annual date I hope will be renewed when we can gather again, although in the next beat I wonder how it can go on without her. Nobody loved the food or the drink more than she did. Nobody was more willing to say what she really thought of that month’s book than she was. (I know this firsthand, having a memory of this exchange: “Listen, your last book didn’t have an ending.” “Yeah, it did.” “Craig, no, it didn’t.”) Goddammit. I should have had time to tell her she was right about that. *If, like me, you believe that public schools and public education are worth fighting for, and that teachers like Darrin Murdoch stand between the rest of us and the wolves at the door, I implore you to offer a gift to the Education Foundation for Billings Public Schools in the name of Darrin Marie Murdoch. Thank you for considering it. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed