|

Originally published November 20, 2020

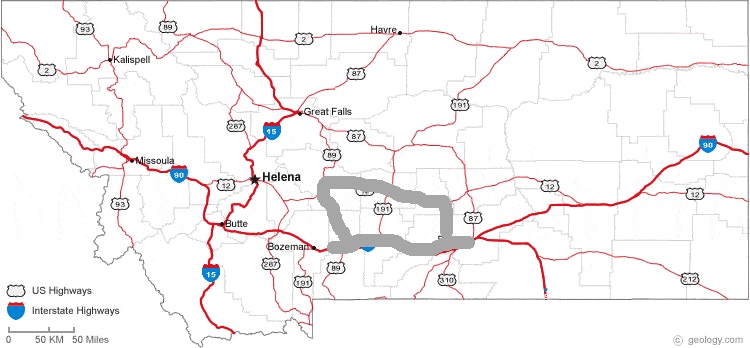

I knew the anxiety was coming before it made a full reveal of itself, when it was lurking several levels below the surface, before my toes began tapping, before my fingers started clenching and unclenching, before my attention started doing walkabouts in the middle of essential tasks. I knew what it was about. I knew what it wanted from me. I’m a restless man, which I grew into after being a restless boy and before that a restless baby. There’s a story that predates any of my memories, one told by my mother. She apparently went to my doctor and said, essentially, what gives with this kid? He stays up late. He doesn’t sleep through the night. Is this normal? And the doctor chuckled and said, well, there is no normal. If it affects his development, it’ll be something to address. If not, not. Well, here I am, fifty years on. We can have a debate sometime about how the whole development thing went, but this much is undeniable: I’m restless. In my work, in my relationships, in my interests, in my physical position on this earth. The coming anxiety was about that last bit. I needed to go somewhere. Our pandemic year makes the particulars of going decidedly more complicated than they were in the Before Times. Who’s going with you? Where? Who are you going to see there? You’re not going to eat indoors, are you? My answers, right down the line: My dog. Livingston, Montana, and points beyond and between. A couple of people. Fuck no. I told my wife on a Monday that I wanted to do it. No, that I needed to do it. On the subsequent Thursday, I did it. We did it, Fretless and me. It was about time. We’ve been back in Montana for a little more than seven months, Elisa and me and Fretless and Spatz the cat. We left Maine and our abbreviated experiment of living there as COVID-19 flared on the East Coast and the byways between Maine and Montana largely emptied out. We got a household and the contents of our lives moved not just once but twice—first into a temporary condo while we waited for the renters to leave the house we still owned here in Billings, second into the house. Through it all, we kept our heads low and ourselves relatively safe, even as the infections rose with ferocity in our old town that had turned new again. We formulated and ditched plans. No, we wouldn’t meet my folks in Denver. Too dangerous. No, I wouldn’t drive to Texas alone to see them. Too much of a time investment, and too dangerous. No, Elisa wouldn’t fly back East to see her mom and siblings. Too expensive, too much quarantining on both ends, too dangerous. It’s been mostly OK. I’ve been blessed with plenty to do, having a full-time job that was already conducted from home before the rest of the country discovered it out of necessity. Freelance jobs come my way—as many as I need and not more than I want. I’ve had a couple of pipeline inspection gigs—did I mention that I’m restless in the ways of work?—that I could drive to. We’ve been more fortunate than many. Our sacrifices—not seeing friends, not traveling at will, keeping our distance, wearing a mask—have been reasonable and not at all onerous. It would be errant of me to suggest otherwise. And yet … When you’re kinetic, a word that sounds so much better than restless, you sometimes have to go. I settled on Livingston for three reasons: 1. I can get there from here. 2. Of all the wonderful towns in Montana, Livingston is the closest thing to a second hometown to me. It’s the place from which one of my side gigs, as design director of Montana Quarterly, emanates. (I have mentioned the whole restless-in-work thing, right? Just checking.) There are friendly faces in downtown shops and on side streets and at restaurants, or at least there were when you could go to such places. 3. Parks Reece wanted an old wasps’ nest I cut down from one of my trees this fall, and he was willing to give me some of his art in exchange. Parks, in so many ways, is the perfect embodiment of the quality that has made Montana my home even though I didn’t grow up here, and a perfect illustration of what I hoped to find in Maine and did not, which compelled my return. I didn’t meet him on my own. He became part of my circle of friends because others, most notably my boss at the Quarterly, Scott McMillion, drew me into theirs. Think of the old trick with the chalices stacked in a pyramid, with wine filling the uppermost cup and cascading down until all of them are brimming. In nearly a decade and a half of living in Montana, this is what it’s been for me—I’ve made friends who’ve had friends who’ve become my friends. They fill my cup. I hope I fill theirs. I try. At Parks’ gallery, while Fretless alternately hid between my feet and ventured halting approaches to as many new people as he’s met in his short lifetime, we talked about this, what I’d looked for in Maine and hadn’t uncovered. Though I found the people there nice enough, there came a juncture where niceties ended and more intimate friendships were harder to penetrate. There’s very much a “from away” label that gets put on people who haven’t been in Maine for generations upon generations. It happens in Montana, too, but there’s often some dynamic tension to it. For one thing, if you’re a fifth-generation Montanan and you have some sense beyond yourself, you have to give some consideration to the idea that you and your people have been stealing what belongs to someone else for a long time. For another, there’s a welcoming nature I’ve found here that I didn’t find there. From the get-go with Montana, I’ve been comfortable with positioning myself as an outsider who found his way inside. I can’t claim it as heart earth. I can claim it as a found home. That didn’t happen in Maine, and it became increasingly clear that it wouldn’t happen in Maine. None of this is empirical, by the way, and I don’t want to end up in the weeds of who or where is more welcoming and why. This is merely my own experience, informed by who I was and when it was that I encountered each place. And that, I’m well aware, counts only so far as I allow myself to follow it. And, really, it’s not remotely my point here. Let’s move on. McMillion and I grabbed a couple of sandwiches and took them to Sacajawea Park, along the Yellowstone River, and had a socially distanced meal at a picnic table. Fretless got his first-ever scraps of people food, little chunks of bread tossed to him by Scott, and while I’ve been steadfast about not letting him become habituated to such delights, I had to relent. If I deserved a treat, so did he. The rapport Scott and I have is a solid and satisfying adult friendship, one I treasure and one that is built out of a few tentpole commonalities and a nice smattering of differences. He’s a hardcore outdoorsman, a hunter and a fisherman and a guy who knows his way around a canoe. I…am not. Scott likes to disappear into the backcountry or onto the vast prairie or down some stream. I think I’d like to rent an RV and park it in the shadow of a mountain, especially if the RV has a satellite dish and I can tune in a ballgame. We’re both big guys, mostly nonviolent, and as such we’ve had separate but similar instances of being drawn into physical confrontations that we’d have rather avoided in favor of a good book. He’s learned in the ways and the history and the art and the literature of his home state. I’m learned in the ways that get his magazine into print. We’re a good team, and we have some good laughs. After lunch, we walked along the Yellowstone River, giving Fretless a chance to stretch his stubby little legs, and we swapped stories of long-ago youthful indiscretions and more pressing contemporary concerns. Before Fretless and I left, I told him I was going to take the long way home, around the Crazy Mountains and up through White Sulphur Springs and Harlowton and on home to Billings. He said that sounded dandy. He probably didn’t remember the last time I’d taken that route. I sure as hell did. When I plotted the trip with Fretless, I didn’t think of just how microcosmic it would be of the total Montana topographical experience, but it really was: In a day’s driving, interrupted by several stops, I saw mountains and river valleys and glaciated plains and bald, flattop buttes and fallow fields. I drove through sunshine and rain and flurrying snow. I drove on dry asphalt and on icy patches where the sun doesn’t alight. I had a whole year in a single day in Montana. I find the mountains and the rivers easy enough to appreciate and admire. You have to work harder to love the prairie or the badlands or a flat stretch where the wind blows so hard that it threatens to knock you down. I’ve learned to express my unabashed ardor for that Montana, the one that generally doesn’t end up on postcards. I live in the eastern half of the state, where the land and the life are harsher and drier and more emptied out. I’ve spent a good chunk of my life now on that side of the state. There’s a depth of field to an endless horizon, and a clarity of thought you can find in pondering it. I missed that while in Maine, too, and hungered to come back to it. It’s become a part of me in unexpected ways. On Highway 89, in White Sulphur Springs, I took note of the little park I’d pulled into on an October day in 2014, when Elisa had been on the other end of my phone, trying to talk me out of a dark hole I’d crawled into. She wasn’t my wife then, just a friend who knew I was hurting, punctured by the twin disasters of an unfurling divorce and an ill-advised rebound romance that was doing what such things do. It was bouncing all over the damned place, battering me with each reverberation. My friend, on the East Coast, told me to hang in, that it would get better, that she didn’t much like to fly but she would get on a plane and see me through it if I needed her to. I told her no. She could sense the turmoil. She couldn’t see the whirlpool. I didn’t want her getting near it. I don’t want to overstate this or minimize what it is to be in true psychological danger. That day, that moment, I think I was in peril. I’d had a cup of coffee with McMillion in Livingston, and he’d talked me through some of the turmoil. He suggested I go back by circumnavigating the Crazies. Spend some time, he said. Let rationality have a go at me. Irrationality got there first. As I drove deeper into Montana, I thought more and more about pulling the car over, parking it, and setting out on foot. That’s when Elisa called. She told me to go to the next town and park and call her back. So that’s what I did. The particulars? I’ll hold tight to those. I’m here. She’s here. The stuff that hurt then doesn’t hurt now. Time and tide, man. White Sulphur looked the same but different today. For one thing, a different man drove into it, in a different year, in a different car, with a sweet puppy in the passenger seat rather than a festering bag of worry and regret. Upon driving into town, I had my mind not on my own pain but on the life of the great writer Ivan Doig, who grew up in White Sulphur and who drew on its impressions for a lifetime’s worth of work. I wondered what it was here that burned into his memory and stoked his imagination. I know a little something about the overdeveloped interior life of a writer; I, too, am afflicted. I never met the man, though I badly wanted to. I would have enjoyed talking about that with him. I read him voraciously starting at age nineteen, and his books were like guideposts into what I wanted to do and to be, even though I ended up treading different literary ground. The longer I do this—and by this, I mean go through this life, although I could just as easily mean attempting to distill the complexities of human life into a story that has a beginning and an end—the more I have to acknowledge that memory is at the thrumming center of damn near everything. It holds out caution. It transmogrifies into inspiration. It informs choice. It drives perspective. As I turned east on Highway 12 and headed into the homeward portion of the drive, memories came at me like bolt-action rifle shots. Here in late 2020, I ran headlong into midyear 2006, when I’d resigned from my job in California and planned a move to Montana with a sort of half-baked plan for a writing life. First, though, I had a trip that had long been on the books, hooking up with my father down in Albuquerque and driving, just the two of us, up to Great Falls, Montana, the part of the state he was from. It seems almost absurd now, as he’s still taking in oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide, but there was an elegiac tinge to that trip when we undertook it. His health had been not so good, and we wondered, or at least I wondered, how many chances we would get. With Fretless, I was driving east on Highway 12. In June 2006, Dad and I were driving west. In November 2020, I kept looking around for touchstones of memory, and I found them in the straightaways and in the rock formations that looked like stacked waffle cookies and in the river that alternately hugs the bends in the highway and rambles off into the distance. I fixated on one particular memory of that long-ago year, of seeing a rusting backhoe on the south side of the highway, stilled and silent and abandoned. In subsequent years, after my initial move to Montana, I would have occasion to go up to Great Falls, and I would spot that backhoe every time and recall the first time I saw it, and I would wonder why it had ever been put there and, more pressing, why it had been left to time and the elements. And brother, if you want to know where a spark of fiction comes from, consider the extrapolations you can make from that starting point. A forgotten backhoe beyond some fenceline. When? Who? What? Why? I looked for that piece of machinery today, in the dying light and amid the snoring chorus of my worn-out pup. It didn’t show. I might have missed it. The relentless vegetation might have overtaken it. Whoever left it there might have come for it at last. Who knows? At the junction with Highway 3, I bore right, Acton just ahead, Billings forty-some miles in the distance. Fretless stirred, activated and attenuated and bouncy, a dog who really should switch to decaf. I snapped one last picture, of the big sky that was over me and over the one who was waiting at home for me. I got on with getting there. The restlessness often gets what it comes for. Sometimes, I do, too.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed