|

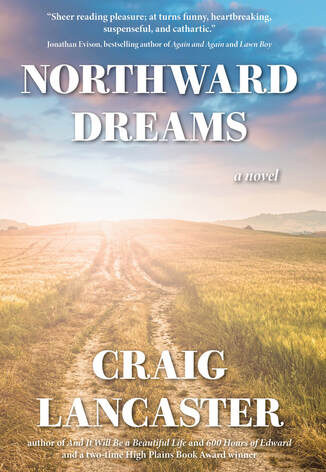

(Note: The original version of this post went up several months ago, in anticipation of the release of my new novel. That release never happened, at least not with the original publisher and not in the original form. But I feel too strongly about this piece to just let it go, so here it is, with some revisions to reflect the novel's current reality.)  I. On The Feeling My tenth novel, Northward Dreams, is just days away from its release date. I’m no more impervious to big, round numbers than anyone else is, and the imminent publication of a tenth novel—particularly when I once had serious, serious doubts that I’d ever write, much less publish, even one—is a good occasion for a bit of reflection. I’ve learned a lot about how to do this, enough that sometimes I’m even prepared to believe I’ve gotten good at it. I’ve learned a lot about humility, which forecloses any chance that I’ll linger long on “gee, I’ve gotten good at this.” (These latter-day lessons in being humbled have been particularly instructive. See the section titled On the Things That Aren't Love for more on that.) I’ve learned a lot about what’s fleeting and what’s durable. I’ve learned that it’s all about love. What that what the last bit looks like, for me, hinges on memory and imagination, the crucial elements of fiction, in my estimation, but also fairly punchless without love. It’s loving the work. Loving the characters who get conjured in the work. Loving each new project with the whole of your heart, even if—and especially if—you must love it enough to let it go. There has been a lot of this, more than I ever imagined there could be. When I get down to diagnosing why an idea didn’t take off the way I hoped it would, I almost always land on a memory to which I’ve insufficiently connected, which bogs down the imagination that is supposed to turn it into fiction, which subsequently demands the love that makes me say “this is not for me.” (If I were as good at that in my beyond-the-page life as I am in my writing life, I wouldn’t bruise so easily. But I digress.) Conversely, the idea that soars, that becomes something I see through to completion, is almost always built on the back of a memory, slathered with imagination, that becomes something else again. It’s almost magical, that feeling, even as it remains hard, word-rock-busting work to bring it forth. I love (that word again) that feeling. I chase it. Again and again and again. II. On Memory and Love A couple of years back, in an interview with Montana Quarterly (where I’ve been on the masthead since 2013), the great Larry Watson said something so profound that my greatest wish was that I’d said it first. Failing that, I cite this quote endlessly, with all due credit to Mr. Watson: I write from memory, not observation. Yet my memories are formed from observations, and then memory and imagination distort those observations into something useful for fiction and something that’s also truthful in its own way. That’s the ballgame, right there. Unsaid, but screamingly evident to anyone who has read Watson’s work, is the part where love comes in. That manifests in doing the work, in riding the work out, in achieving empathy with your characters, in knowing when to make the gradual turn from I’m writing this to engage my own need for the work to I’m writing this for someone to read someday, and thus I must be attentive to what it needs to be. Love is showing up faithfully. Love is holding at bay the world that will threaten your enthusiasm, your want-to, your ability to separate those things over which you have control and those that are mysterious variables. Love is having a standard for the work. Love is absolving yourself when, say, a pandemic swallows up your work like it never existed in the first place. It did. Your love made it manifest. Love is also forgiving yourself when you could have done better and somehow didn’t. Love is believing that you’ll do right by it the next time. Love is faith, and you’re gonna need a lot of it. Arthur Miller—I borrow only from the best—knew something about the staying power of the deeply imprinted memory. Perhaps nothing is as creatively propulsive as the blown chance, the missed boat, the shameful moment, the deep regret, the thing you ache to understand, the love you couldn’t hold. Here he is: Maybe all one can do is hope to end up with the right regrets. If you’ve had a bit of therapy—and only about eight percent of us have, which means ninety-two percent of us are in deficit—you’ve probably been told that regret is a feeling wasted on the unsustainable belief that you should have been perfect. Insofar as it applies to our lives and how we face up to them, I’m inclined to concede the point. But for the author who mines memory for stories, regret—particularly the right kind, which Miller doesn’t identify and thus is open to personal definition—is creative fuel. As I look back on ten novels, I see work and characters suffused with what I could give them through my grappling with memory and regret. Neurodivergent Edward Stanton (600 Hours of Edward, Edward Adrift, Edward Unspooled) and his fights with an illogical world. Mitch Quillen and his intractable father (The Summer Son). Hugo Hunter and his clay feet as a fighter and a father and a friend (The Fallow Season of Hugo Hunter). The Kelvig clan and their town and the pulling apart of what binds them (This Is What I Want). Sad-sack Carson McCullough and the demise of the newspaper business (Julep Street). Jo-Jo and Linus and the vagaries of attraction (You, Me & Mr. Blue Sky). Max Wendt and the status quo he doesn’t see crumbling (And It Will Be a Beautiful Life). And now, Northward Dreams, perhaps the most personal work of them all, one that required me to find the memory—and, always, the love—and enough imagination to make it something more than a transcript. So much more. So surprising in the end. So familiar that it could have kissed me. I’m in love. It keeps happening. III. On Imagination and Love How does this memory-fortified-with-imagination-backed-by-love thing work, in practical terms?I have an object lesson for that, drawn from Northward Dreams and its ingredients. The memory: If I’m prompted to give a short-hand accounting of who I am and how I got here, I say that I grew up in Texas and found my way to Montana as quickly as I could. The truth is a bit more nuanced. I wasn’t that quick. I got here when I was thirty-six years old, time enough for a dozen places in the interim that I tried, to varying degrees of success to make home. My first home, in fact, after I was born in Washington state and adopted by my parents, was in Mills, Wyoming, a little bedroom community north of Casper. For the first three years of my life, I lived in tiny clapboard house on an unpaved street, which sat across the street from one of the town’s water towers. After my mother left my father and moved us to Texas, I was largely absent from Mills save for occasional summer visits to see my dad. But the image of that water tower embedded in my psyche. Whenever I would see one like it, particularly in my suburban Texas town, I would feel the pangs of separation from my father. The imagination, in excerpt form: Ronnie goes down to the floor with his boy for a close-up view of the gas station in miniature. He watches as two round-headed figurines in a car, into which they fit like pegs, ride the elevator up to the top floor and the door opens and the car rolls out and careers down the ramp to the carpet beneath them. “Ain’t that something?” he says, and the boy squirms happily. “I got it for Christmas last year,” Nathan says. “I remember,” Ronnie says, a harmless lie, he thinks. “Hey, I saw that kid Richard, your friend, the other day. He says hello.” “He’s nice,” Nathan says. “Yeah, he’s a good kid.” Nathan bounces up and grabs his father’s hand. Ronnie clambers to his feet. “Come here,” Nathan says, tugging him. “OK.” Nathan pulls him to the window that looks out upon the suburban expanse. “See that?” “Yeah,” Ronnie says. “Buildings.” “No, that.” Nathan points, insistent. “What?” “The blue thing.” Ronnie stares down. “What blue thing?” “No, there.” The boy redirects his indicator, trying to get his father to follow the line. “The water tower?” “Yes.” “Yeah, I see it,” Ronnie says. “That’s where you live.” “It is?” “Yes. I live here. You live over there.” “No, son.” “Yes.” “No.” Ronnie makes a quarter-turn, facing the wall. He points at the blankness of it. “It looks the same as our water tower, but I live a thousand miles that way. North. Where you used to live.” He turns back to the window and points again. “That over there, that’s east. Understand?” “No.” “Well, come downstairs, Sport, and I’ll try to explain it, OK?” The love: It starts with what I feel, and have felt, for my father, a love that’s been constant but ever changing, ever shifting depending on the circumstances we find ourselves in. The unquestioning adoration I had for him when I was a little boy got replaced by an exasperated pity the more I learned about him and the more I witnessed. That, in turn, got supplanted by the responsibility I take for him in his dotage, the insistence I have of seeing him off this mortal coil and keeping fear, terror, and pain as far from him as I can. As his infirmities grow and he lashes out, I find myself with more and more days when I love him and simultaneously hope I can find a way to like him again. It’s not for wimps, this love thing. The water tower the boy points at insistently was, and is, in a Mid-Cities suburb between Fort Worth and Dallas, a town called Hurst. I used to climb into the tallest tree of my neighborhood in an adjoining town and find it on the flat horizon and try to convince myself that it was Mills, Wyoming, and that my father might be there at the base of it. I didn’t know north from east in those days. I couldn’t have envisioned the magnitude of a thousand miles. I just knew blue, cylindrical water towers and that one was in proximity of a man I missed. I tucked it all away. Years later, it came pouring out of me, a strong current of memory washed in imagination. That’s love. IV. On the Things That Aren’t Love

Soon after my third novel, Edward Adrift, came out in 2013, I was making enough money in royalties to grant serious consideration to trying to make a go of it as a full-time novelist. I had the big-time New York agent, a slew of foreign translations, a full calendar, and novels-in-progress lined up on the runway. My then-publisher had feted the onset of our relationship with “we want to be in the Craig Lancaster business.” That’s something—indeed, I suspect it’s something that most any author not in the one percent craves—but it’s not love. It’s validation, it’s success, it’s the fruits of one’s efforts, it’s unadulterated luck, but it’s not love. Love is what you give yourself when the royalties dry up, the big-time New York agent moves on from you, the foreign translations are harder to attract, the calendar is empty, and the ideas are taking on rust. When your publisher doesn’t want to be in the “you business” anymore. When the publisher you subsequently love makes promises that don't pan out and you pull a book just a day before it's supposed to come out, knowing you'll end up hating yourself and maybe him if you don't. And you don't want to hate anybody. Find love through that. It's not easy. But it's worth every effort you can give it. These are all things that can shoot your horse right out from under you. I’m not suggesting that you—or anyone—should just buck up and get through it, as if it’s not there, in your path like a boulder you can’t circumnavigate. Lean on your supports. Get your ass into therapy if you need it (ninety-two percent of us do!). Divert yourself with a hobby or a road trip or whatever. Take some time off, if that’s what’s calling to you. Don’t stop pushing, if pushing is what’s demanded. And while you’re doing all of that, remember the love. The love of a memory, an idea, an approach. The love of the work. The love of the characters and the settings and the structure of what you’re trying to create. The love of revising it and honing it until it’s just what you want. The love of taking the finished thing—the first or the tenth or the hundredth—and offering it up with a hopeful, open heart. I made this. I fell in love. Again.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed