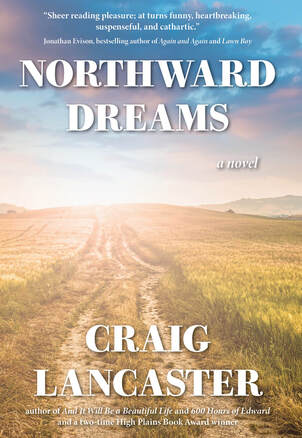

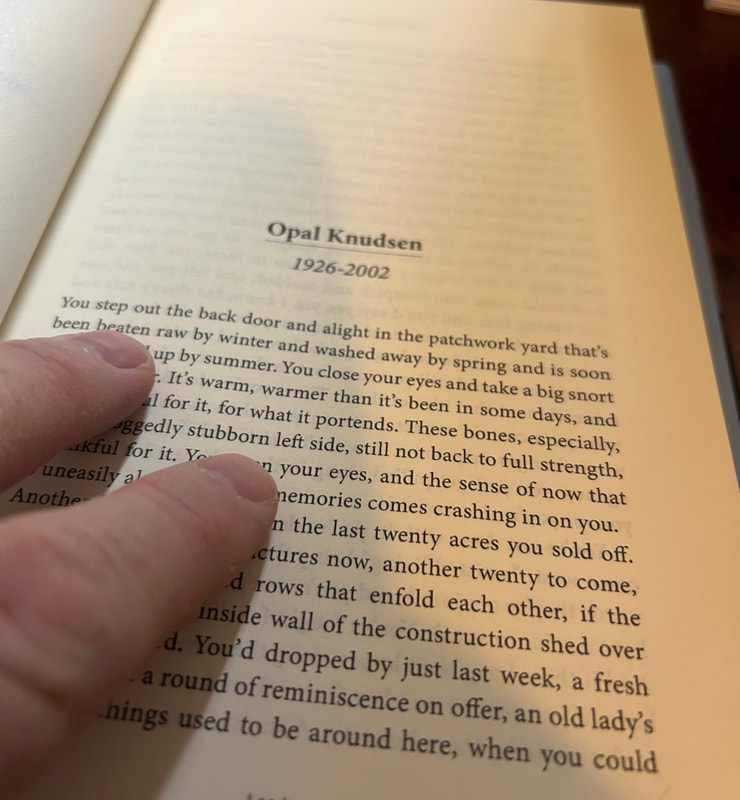

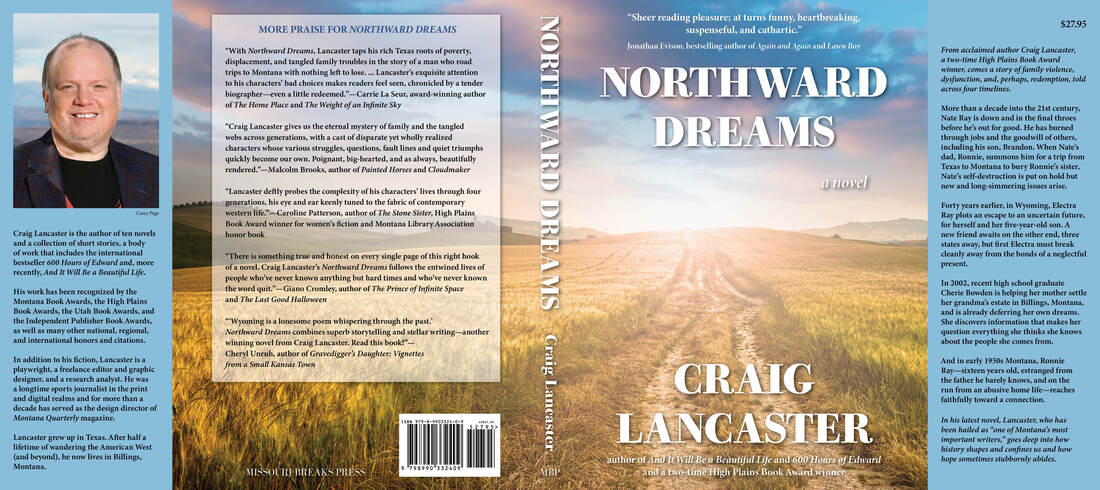

Now that Northward Dreams, at long last, is out in the world and available in hardcover and e-book (with the audiobook on the way!), I'm enjoying the payoff for all the lonely work of writing it and preparing it for delivery: the idea that there are people out there reading it. (Thank you!) If you're one of those people, you didn't have to go far—the very first words—to encounter one of the book's devices, for lack of a better word. Spread out among the 32 numbered chapters of the book, which encompass four timelines (1952, 1972, 2002, 2012), are nine chapters that focus on individual characters who inhabit the book. These chapters—which I've heretofore been misnaming as intercalaries—exist outside the story's established timelines and illuminate aspects of the characters that inform the whole of the narrative. They're also written in second person, a choice I expanded on in this interview with Chérie Newman: I think I went with the second-person point of view initially just to talk to them: Here's what's happening to you, what you're feeling, why it has gone the way it has. Any notion I had about changing that up went away once I saw the effect. There's an immediacy to the POV. Those characters are illuminated in ways they couldn't have been even in close third person. So that's why I did it, but this isn't really about that. (It's not expressly a craft talk.) Instead, I want to dig into who these characters are and why they spoke to me—and why they allowed me to speak to them—without giving away the essential plot, so to speak. (Before I get too far into that, about the errant use of intercalary: These chapters don't quite fit the accepted definition because they do involve main characters and are less about theme, I think, than they are about backstory. For a more traditional view of the intercalary, think of the turtle chapter of The Grapes of Wrath. I certainly do—I referenced it many years ago in a short story.) Opal goes first because...she goes. She dies, right there on Page 13: You kneel, the knees of your jeans in the mud, and you take the clipping shears from your apron pocket. You size up the job, and you pitch forward into the bush. Two crows, languid on the telephone line above, bear witness. Across the way, the hammering goes on, beating out a rhythm, a simple song for the dead and gone. Here's the thing about Opal, though: She is, in a significant way, the master key to the story, the connector of 1952 and 1972 and 2002, when she leaves us, and even 2012, when she's a full decade gone. Without Opal, the connections among Ronnie and Cherie and Nate and Electra—the four primary characters of those timelines—lack resonance. And without those four, Oscar and Anna and Charley and Brandon are four characters in search of a story. In subsequent installments of this series of posts, I'll introduce you to all of them. You'll just have to believe me that they all fit, eventually. Or read the book, please! (Be sure to note in comment box that you wish for a signed copy.) (Purchases through Bookshop.org can be dedicated to the independent bookstore of your choice, an excellent option for those who prefer online shopping.)

0 Comments

3/15/2024 0 Comments Northward Dreams: Chapter 1(Note: Now that the novel is imminent, here's a little taste of it, from one of the four timelines threaded through its 314 pages. The book has 32 chapters—eight each from the four timelines—and nine intercalary chapters told outside the timelines, each focused on a major character. Here, in the first full chapter of the book, we meet Nate Ray.) August 2012 | Denton County, TexasThe jangle of the cellphone—unmistakable, jarring, relentless—enters the slipstream of a sunken reverie, a mishmash of now and then, of events known and impressionistic, of faces presented and obscured, of times endured and never breached. As the tone loops through for a second run-through, then a third, Nate Ray tumbles nearer consciousness. His hand emerges from under the sheet and cuts off the ringer, then slips back into the crumpled bedding left sticky and sour from night sweats. The light comes in now, defying the inclination toward running down sleep again. Nate’s eyelids flap. He’s on his back, staring into the plastic molded ceiling, fixated on the AC unit that up and stopped whirring a week ago, more maintenance deferred until god knows when. She’s gone. Nate knows that sure enough even with his eyes closed. It was a jackpot the night before that she’d even come around, and there had been some unspoken--thank Christ—finality to it all, a let’s-have-one-last-hurrah roll together through the night. He’d fallen asleep with his nose in her chest, that much he remembered, and here he is alone, as it should be, no memory of her eventual movement toward the door. Nate folds himself up to sitting, halfway at least, elbows at his sides like hydraulic lifts, pushing him up. He’s making an inventory now of every ache—the ones chronic, like the left knee Doctor Simmons at the VA says will need replacing, and the ones that come on without warning or an appointment. Next, he swings his legs toward the floor, cupping the trouble knee with his hands to keep it stabilized. The problem, of course, is that Doctor Simmons, wise though he may be, isn’t the authority on exactly when the knee will be dealt with and who’ll be carrying the freight on it. It’s the latter point on which Nate and Veterans Affairs find themselves at an unbalanced impasse, Nate’s contention being that an unremarkable stint in the navy ought to be good for a new knee, at least, and the VA’s contention being that, well, no. It’s a staredown the bureaucrats can play into eternity—it’s not their knee, after all—and the list of deferred maintenance grows ever longer. The melodic ping comes, alerting him to a message, and Nate grabs the phone and flips it open to see what he’s missed in the fitful night and early morning. The deliverer of the latest voice mail, Ronnie, can wait--forever would be nice, Nate thinks, but fat chance of scoring that kind of luck this late into things. Karen’s message, dropped in at 6:23 a.m., no doubt soon after she granted her own release from the trailer, bears listening. I tried to wake you. Figures. You know, I keep hoping you’ll actually surprise me and show up. Guess I’ll know in an hour and a half or so. Listen, Nate, if you don’t, I’m gonna need you to hitch up and get off my property, OK? It’s too hard. “Too hard for the both of us,” he says, and he deletes the message. It’s a hell of a thing, he thinks not for the first time, to have these get-togethers be a point of such pain when daylight comes around again and reconsideration is put on the table. Everything he’s taken, she’s offered first. The job he never wanted. The pastureland he parked the trailer in two months ago, useful enough but also not as rare as gold. She’s doing him a favor, sure, but it’s not the last one he’ll ever have a chance to call in. He’s parked the rig in other places at other times, and he reckons he can find someplace new if it comes to that, if she’s really had her fill, or if he’s had his. It’s gotten to the point that she wants something he’s not prepared to give and she’s not prepared to say, and this indistinct thing lies down between them at night, taking up most of the bed. He moves into the living area of the trailer—he’s seen this space called “the great room” in some of the newer models he’s gawked at down at Camping World, but this isn’t that in any configuration. It has a two-burner gas stove, the propone nearly drained, and a refrigerator that runs cold, praise be, but also cultivates mystery flora sprouting from foam boxes holding half-consumed takeout dinners. No microwave. No dishwasher. He’s overdue for a black-water dump. A single basin aluminum sink ringed with gunk from who knows when. Sitting adjacent is a tattered couch, shedding foam like dandruff from the holes in the arms, and it lies aligned with the thirteen-inch color TV he’s strapped into place with old speaker wire and which pulls in two over-the-air channels, and sometimes three if it’s not raining, from the antenna he’s rigged up on the roof. Home. Nate takes a swig from the open bottle of Canadian Club that sits on the countertop. He cringes and squints and he smacks his lips and savors the washaway of morning tacky mouth, and he takes another for good measure, hair of the dog and all that. The realizations and lines of thought that come to Nate these days don’t lay out in parallels or even perpendiculars. They’re at odd angles, lying crosswise against each other, overlapping, one thought the ignition source for some other bleak firing of the synapses that, sometimes, improves his position but mostly leaves him befuddled and behind the flow of things. The whisky has set his mind on spirits, which oddly, or maybe even predictably, brings into his head the voice of his learned son, the word pusher, who told him once about how whisky, no “e,” refers to the Scottish and Canadian and even Japanese grain spirits but that whiskey, full-on “e,” is for the grain spirits distilled here and in Ireland, and anyway, you shouldn’t drink so much of it, Dad, because you know how you get. “Well,” Nate had said, in another loosing of the tongue that he’s regretted far longer than it ever took him to say the words, “that’s fascinating and all, but I ain’t interested in the vowels. Just the dollar signs and not too damn many of those, thank you very much.” He needs to call Brandon, he knows, but he needs to call Ronnie first, because that’s the more loathsome chore and the one that might divert him directly back to that bottle and the identical one under the sink, if memory serves right. Nate flips the phone open again and sets it on the countertop for easy dialing. He roots through the fridge and brings out a couple of eggs, turns on the burner and hopes for enough flame to get them scrambled, and when the works are all up and running, he patches through the number to the old man, who answers on the second ring with “You listen to my message?” “No.” “Why the hell not?” “I’ve missed you, Pop. Couldn’t wait to talk to you.” Nate reaches for the bottle, has it by the neck like a pullet, then lets it go. “Sure.” “What do you need?” “I need you to come over and spring me from this mortuary, which you’d know if you’d listened to me in the first place.” “Oh. Well, why didn’t you say so?” Nate says it only because he knows it’ll bind the old man up something fierce, and the sputtering “I goddamn did” comes back as validation. Nate again toys with the bottle of whisky. “OK, where we going?” A summons from Ronnie isn’t new or notable. The place he calls “this mortuary” is, in fact, a perfectly respectable assisted-living center just north of Fort Worth, which has taken in Nate’s father for the low, low price of his monthly Social Security check, his retirement disbursement, and the keys to a single-wide trailer house that’s long since been liquidated and picked over for cash. When Ronnie gets restless, he calls for a ride, and Nate can usually settle him down with a middling beer or two and a plate of decent barbecue. “Montana,” Ronnie says. “No, really.” “Really.” “I’m not going to Montana.” “You damn sure are. Gonna pick me up first, though.” “Why?” “Because I said so.” The eggs, neglected, run hot, headed for hardness and, eventually, carbon, and Nate splashes them with the whisky. The liquid hisses and bubbles, and Nate scrapes at the mess with a spatula. “Gotta go,” he says. “No,” Ronnie says. “Wait. I really need your help with this.” Nate turns off the gas, lifts the pan with a crusted rag, slaps it against the rim of the sink and splatters the contents. “Why?” “Your aunt died.” Nate blinks. “Linda?” “Yeah.” “Your sister, you mean.” “Yeah,” Ronnie says. “I didn’t know her. Not my business.” “Look, look,” Ronnie says, and it’s almost plaintive, almost vulnerable, a damn rarity from him. “I need a ride. Come on. Don’t make me beg.” “I can’t afford to make that trip.” Nate looks around him at the squalor he’s managed to ignore until the moment it all falls over onto him. “Ride the bus if it’s so important to you.” “I’ll pay.” “Right.” “I have some cash squirreled away.” “How much?” “Enough. You coming?” Nate rather doubts his story. A room, Ronnie has. Three squares, ditto. Somebody to clean his linens and buck out his trash, certainly. Even some old coots for games of penny ante, and who knows, maybe he’s taken down a modest fortune there. But he’s cash-poor. They’ve been through this, a year and a half ago after the third heart attack, liquidating everything they could before Ronnie went in. But whatever. If he can’t put the first tank of gas in the truck, it’ll be a short trip. Nothing better to do. “Yeah, in a bit,” Nate says.  (Photo via Pexels.com) (Photo via Pexels.com) Nate packs for brevity, not comfort. It had been a chore to pull even the slightest of details out of the old man. Where we going? Montana, I told you. Yeah, but where? Billings. How long we gonna be there? A day or two. Not long. What’s it to you? Got something better to do? Nate supposes he doesn’t, which explains the duffel that’s filling with underwear and socks and two pairs of jeans and enough T-shirts to scoot through a week if he can put them to double duty. Because why the hell not, in terms hypothetical (Brandon and his vocabulary in his head again) and promissory. Nate wonders how much the rascal has stashed away, how long he’s had it, whether he had it in January, when Nate called him from the drunk tank, looking for bail, and Ronnie had said, “Sounds like you’ll have time to think about some stuff, boy.” At last, he pulls the flask from his hip and tosses it atop the clothes, thinking maybe he'll leave it alone en route. Maybe. Even the light task of packing leaves him lightheaded and sweaty, the trailer an oven as August throttles up the heat, last night’s drinks coming through his pores. Would thirteen hundred miles northward bring some respite from that? Nate surely hopes so. He’s nearly ready when Brandon lands in his thoughts yet again, the phone call he’s still to make, the favor he’ll ask for with no decent odds that the answer he wants will be coming. What then? Well, another dance with Karen, another negotiation, another fractional gain, or maybe just a loss put off until it can be better absorbed. Nate sends out the call. “Not a good day” comes the response upon pickup. “Just as well,” Nate says. “I need you tomorrow.” “What?” “Can you come get this trailer, tow it back to your place?” “My place?” “Yeah,” Nate says. “Big request, I know. Wouldn’t make it if . . . well, I wouldn’t make it.” “No. I can’t stash it here.” “Just for a couple of days, that’s all.” “Your truck get repo’d?” “No. But nice you’d assume so.” “Educated guess.” “I’m taking your grandpa up to Montana.” “Lucky you.” Nate draws a hand, stinky with cheap Canadian, across his nose and mouth. “Nothing you’re thinking that I haven’t already thought. Nothing smart you’re gonna say that hasn’t already flapped out of my gums. Can you help me?” “I guess,” Brandon says. “Kelly’s not gonna like it.” “Well,” Nate says, “add it to my tab.” “I’ll take ‘Things That Will Never Be Paid’ for $600, Alex.” “Huh?” “Nothing,” Brandon says. “Never mind. I’ll get your rig. But don’t leave me hanging on this or I’ll sell it for scrap. I’m serious.” It’s not an idle threat, Nate knows. The squaring away of Ronnie’s affairs had put a fright into him, and between benders, he’d made sure his own son’s name was on everything so there wouldn’t be any undue burdens if, someday, they found Nate’s abandoned carcass down in Corsicana cozied up to some nice piece of ass. Not a bad way to go, all things considered. “I hear you,” Nate says. “Thanks.” There’s no avoiding Karen in the leaving, and Nate has concluded that avoidance is already well played out as a relationship strategy, if relationship is even the word for what the two of them have been playing at. It’s more like a friendship rooted in another time and place--high school, Jesus Christ—that has somehow endured, changing both broadly and imperceptibly through the decades and the weaving in and out of each other’s sphere, until they were left with what they have: an employer-employee setup where the former is forever frustrated at the latter’s chronic absenteeism, a personal rapport that finds communion in a bottle, and enough comfort and shamelessness with one another to get naked and have a go from time to time. Nate sees now, in hindsight, that it’s the reintroduction of sex into matters that’s fooling with them, more so, perhaps, than even the not showing up for work and the booze. She’s been hinting that it portends something more for them, something deeper and more meaningful, and all the while he’s been hoping for nothing more than another hard-on with the next spin of the rock. Time’s coming fast when a guy won’t even be able to count on that. Whatever she’s got in mind can’t work like that. Nothing can, he thinks. He stops off at her store on his way to the interstate, peels back the automatic window on the passenger side. She comes out and frames herself there in the gap, elbows poking across the boundary line. “This is my answer, I guess,” she says. She looks tired, no doubt because she is tired. She’s built something here—more than a farm stand, more than a feed store, a place with knickknacks and baked goods and wooden spoons and all kinds of other stuff the interloping suburbanites from down around Dallas and Fort Worth find irresistible—and it siphons off her life in chunks. She really could have used his help, and that he never had any intention of giving it to her takes him only halfway to regret. “Going north,” he says. “The old man wants to see Montana.” A laugh squirts out of her. “The two of you, together, all the way up there?” “Yup.” “Well, I’m grateful I’m not the cops in Colorado or Wyoming when you guys have your blowout. I’m grateful for that, at least.” He leans across the distance. “You’ve been real good to me, Karen. Better than I have coming.” “You’re goddamned right. So what?” “Brandon will get the trailer out of here tomorrow. He promised me he will.” “His word I can trust.” “All right, then,” Nate says. “Be seeing you.” He engages the window, then she smacks the rising glass with an open hand, and he lowers it again. She leans farther in this time. He holds his spot. “Take care of yourself out there, Nate,” she says. “I probably won’t be pissed at you forever, but I’m sure gonna try.” He nods, smiles, gives her a dorky salute that brings another sputtering laugh. “Forever’s a long time, though.” © Copyright 2024, Craig Lancaster |

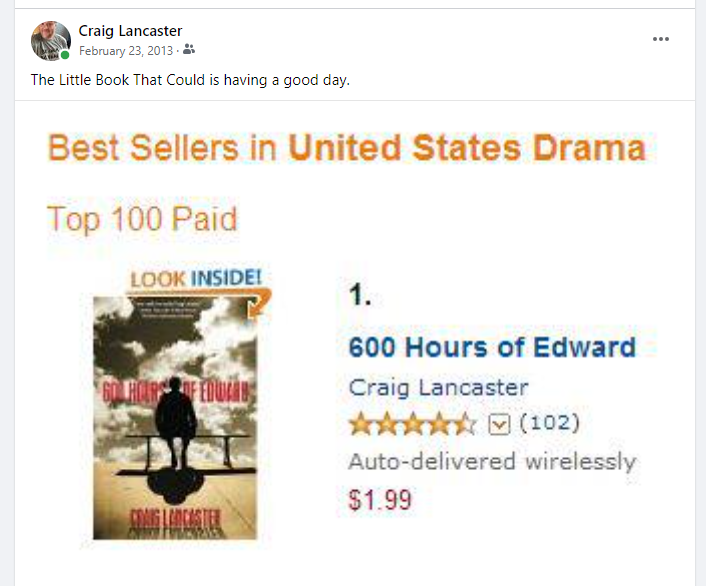

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed