|

7/17/2022 0 Comments On the Struggle I just—and when I say just, I mean less than an hour ago—finished constructing and printing out the interior print file for Elisa's forthcoming novel, All of You. I'm proud for so many reasons: that she's written another banger, that she's making tangible progress toward getting it out there, that I am able to use a skill I've developed to help her. Elisa believes in this novel, and she's reached a juncture in her career where putting it out herself and realizing her own vision for it is of paramount importance to her. And that gets at why I'm most proud: A year ago, she wasn't sure she'd ever be here again. Three years ago, I wasn't sure I would be. Much of the joy of writing and publishing and connecting had been sucked out of it, for both of us, for similar and divergent reasons. And, listen, if you can't find the joy, there's not much reason to keep going. The difficulties are too numerous, the frustrations too pitched, the dead ends too abrupt in the best of circumstances. Joy, and its cousins purpose and determination, helps carry you through all of that. I won't speak to how Elisa lost joy and found it again; that's her story to tell in her way. But I can speak to my own journey ... Facebook is a scourge, mostly. But it's also a scourge with features that aren't easily replaceable through other means. I can't call up my nieces and nephews on the daily and ask what's going on their lives—I mean, I could, but they'd quickly tire of it, and I'm just not constituted to operate that way—but I can see every important turn on Facebook. I can be conversant about what they're doing. I can feel connected to them. Similarly, there's nothing quite like Facebook's Memories feature to remind you of the way things once were. Sometimes, it brings into sharp relief just how different your current circumstances are. Elisa and I get this a lot, especially this time of year, which synchs up with the first summer of our courtship—The Magical Summer of 2015, as we like to call it. And so we sit at the breakfast table, older, paunchier, scuffling harder to pay bills, not knowing when or where our next vacation will be, and we sigh contentedly at the memories of a time when royalties were flush, there were no jobs to go to, and we could just disappear without worrying where the next check was coming from. And we say "gee, wouldn't it be nice to experience that again?" and we agree that it would be, but we're not really thinking about how much richer life has become in other ways, lost as we are in the haze of memory. We're not thinking about the house we bought together, the pets we love, the history we're building. We're thinking about being financially carefree and unbound by anything other than our imaginations. They're pretty sweet, those memories ... If you've read the past several paragraphs and thought, OK, great, Craig, but that was a bunch of sentimental claptrap about life and leisure and I'm here for the struggle with art, let me say this: I find it impossible to separate the two. Those memories from 2015 beguile us, in part, because of what fell out from there: Love and marriage and commitment, yes, but also struggle. We both wrote and published books we loved and believed in, same as we had before, only those subsequent books weren't commercially successful in the same way their predecessors had been. We fought against ourselves to recapture what we thought we'd lost, not really having any idea what it was or why it had seemingly gone sour. We got dumped by our publisher, and while it would be nice to be above it, to greet such news with an attitude of "their loss," the simple fact is that the losses felt very much like ours. It felt like rejection, because it was rejection. It hurt because we are humans, and we bleed when we're cut.

However ... It's important to know that, even as you build yourself up as special, you're not. Rejection isn't your burden alone; everybody grapples with it. A change in trajectory isn't singular failure that's on you; that's life and what happens sometimes when you have the audacity to live it. It took a while to come out of that depressive trough. It took a while to find a new footing. It took a while to want to get in there and slug it out again. For me, the breakthrough came when I realized that my happiest place was inside the work, where it was just me and the stories I'm trying to tell, where the measure of progress is keeping faith with what I'm attempting to do by showing up, every day, and doing a little bit more to realize it. When I rediscovered that, the rest began falling in. The publishing partner with whom I want to bring these stories out, who believes in the work the same way I do. The reconnection with a sense of fulfillment (not necessarily happiness, which is more transient and thus, honestly, less valuable to me). Exterior validations of the work. But always, always, it's the work. I see that in Elisa now, the spark she has rediscovered with this new book. She's fully into her own joyousness, and you can take it from someone who's seen this from her before and worried when it went away for a while: Look out. She's got this.

0 Comments

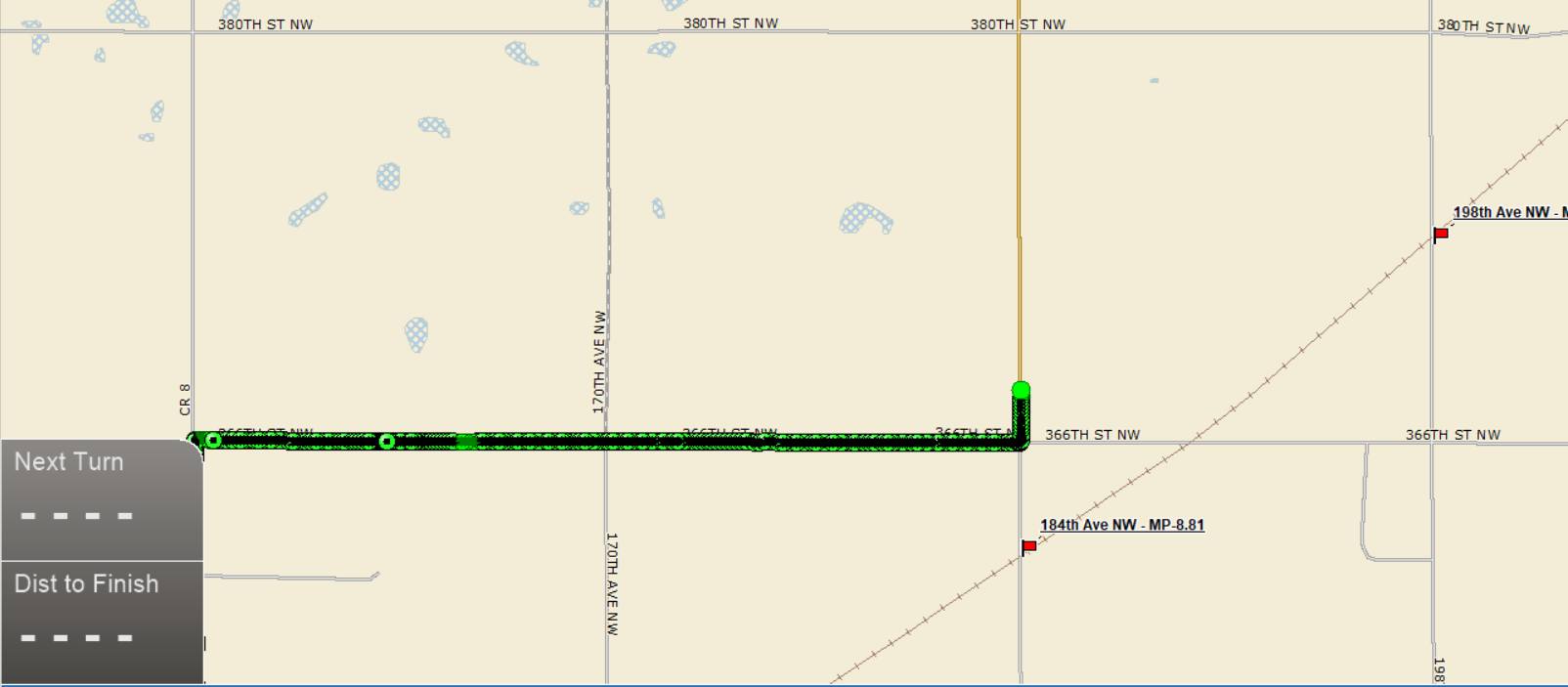

6/25/2022 2 Comments The Road Called, and We AnsweredHere we are, nearly halfway through 2022, and I've only just caught up to reconciling something that happened in late 2021. (I suspect this is either because I'm slow on the uptake or because I just hadn't taken the time to lean into my feelings and sort them out. Maybe even both!) At any rate, at the end of the year, the company for which I'd done some occasional pipeline inspection work for the past several years folded up its U.S. operations. Just like that, I was out of a gig. First, the important stuff: It wasn't more than a trickle of an income stream, so it's not like I was jobless or under the threat of imminent financial disaster. It wasn't and never had been a career, so I wasn't grappling with the loss of self. The point being, it wasn't a massive blow to the bottom line or self-identity. And yet ... It was a blow, undeniably. I felt the absence, and I felt a little unmoored by the fact that I didn't have any work trips coming up. I found myself thinking inordinately about the places I would commonly go on these work trips—Buffalo, N.Y., and Chelsea, Mich., and Michigan's Upper Peninsula, and the far reaches of Minnesota and Wisconsin. My thoughts would drift to Minot, N.D., where I'd gone for my first such job, way back in 2015. And then it occurred to me: What I'm really missing here is that liberating sense of being gone. I'm 52 years old, and I've never lost that urge toward motion, travel, getting in the car and going, any direction will do. I like hotels and corner restaurants. I like people watching in places where I don't know anyone. I like seeing what's over the next horizon, even if I've seen it before. By now, I surely most know that it's incurable. So I told my understanding wife that I needed to go, and I packed up the dog and a week's worth of clothes, and I went. The idea was to go to Minot and, from there, launch revisits of a few pipeline routes that emanate from there. The Minot part was easy enough. The rest, though, went against my expectations. Here's a glimpse (material stolen from a subsequent Facebook post):  See the orange post there? I tracked my first pipeline tool from that site (smack in Berthold, N.D.) back in 2015. See the orange post there? I tracked my first pipeline tool from that site (smack in Berthold, N.D.) back in 2015. I haven't missed the pipeline work—which, you know, is work—nearly as much as I've missed the travel and the solitude. The solitude most of all. I don't think happiness exists in a fixed place; it is, instead, what you make of it and where. But if I'm wrong about that and happiness really is out there in a place you can pin on a map, then I'm fairly certain that place is on a tertiary road in some lonely precinct where no one goes on vacation. I came here thinking I'd ride the full length of a few lines, stopping at every checkpoint and taking them in, and I was wrong about that. I don't need that much immersion. I just needed to be out. Away. Gone. Just for a few hours at a time. God, how I loved it. God, how I've missed it. On our last full day in North Dakota, Fretless and I rode a small portion of an 85-mile line that runs northwest from Berthold, N.D., to the Canadian border. It was, simultaneously, a total kick of nostalgia and an entirely new experience. The only time I did this line for real occurred in the deepest of winter, 2017. It was bitterly cold that night. The snow was in drifts. The wind blew the snow around in ways that would mess with your perception of things. On those dirt roads, some of them just two-track, you'd see a pile of snow and you'd stop the car and get out, the wind biting your face, and you'd walk it first to make sure you wouldn't get stuck. You don't want to get stuck, believe me. It's happened to me, more than once. It's bad. I once waited for seven hours in Wisconsin, my work vehicle sunk to its axles in a blizzard, for a tractor to come and yank me out. You don't want this. See the pipeline marker in the photo above. To do my job, I'd have to wade through snow, sometimes chest-deep, and put my sensory equipment there to record the tool passing by, deep underground. Then, after a passage, I'd have to wade back out and get the equipment, then try to swim back to the vehicle, hoping I didn't get hung up alone out there. Meanwhile, the tool was zipping along to the next checkpoint at about 7 mph, which is really hauling ass. It was desolately lonely and dark and cold and scary. I loved it so much. The line parallels railroad tracks (see the map above), which cross the road at uncontrolled intersections. In the night and the cold and the dark, snow flying sideways and obscuring your vision, you'd have to be careful, hanging out in those places. When Fretless and I went out, though, it was different. Warm and clear. Sunny. No snow. No drifts. More red-winged blackbirds than I could count, although not one of them stood still long enough for me to get a picture. Farmland was verdant with moisture, not gray and white and foreboding like in my memories. That night I ran the line for real, in March 2017, we finished at the border and the snow was coming down in massive clumps. I drove to my waiting hotel in Williston, more than 100 miles away, unable to see a damn thing, holding my phone in front of me and using the GPS program to keep my truck on the road, or where the road was supposed to be. I didn't tell my wife about that until a day later, when I was safely home. I don't miss that kind of stuff. A little more than a week ago, when I'd had enough, I asked Fretless, in the backseat, if he wanted to go back to the hotel. He wagged his tail agreeably. I cracked the windows, letting in some fresh air, and we got the hell out of there. It was glorious. Every little bit of it. I had to work the evening of getaway day, and long gone are the days when I can drive for eight hours and work for another eight, so we stayed that night in Sidney, Montana, another dot on the map rich with memories. Again, borrowing from Facebook:  See the windbreak there? That's on the southern edge of Fairview, Montana, a little town that straddles the Montana-North Dakota line. In late summer 1981, when my dad was in the midst of moving his drilling rig from one town to another, the right-front tire on his International Harvester Paystar 5000 blew out and he, with much effort, brought it to a stop right there. I have a clear memory of this because I was in the passenger seat, so it was my side of the truck that dipped precipitously, as if we were going to pitch over on our side. I also well remember it because it was a classic bad news-good news scenario. Bad for obvious reasons, and for these reasons: Dad's hired hands, who'd ordinarily be following him, had gone out ahead of us by a couple of hours. We were alone. Good because there's a house right there, and a small town just ahead. Easy to make a call, even in 1981, and get some help dispatched. Now, lemme ask you this: What do you suppose the percentage chance was that this boy, who lived at the time in Texas, 26 years later would marry a woman from tiny Fairview (population now 900, but much smaller then)? As it turned out, 100 percent. (We divorced seven years later, so it's less a fairy tale than an interesting coincidence. But still.) OK, let's move a dozen miles down the road to Sidney. That train engine, in Veterans Memorial Park, with Fretless offered for scale? I climbed all over that thing that summer. I was 11 years old, and that's pretty much the recreation that was available to me. The city fathers hadn't yet fenced it off, so I was free to clamber wherever I could get to. I also chewed illicit tobacco, given to me by my dad's helpers, who encouraged me to have all I wanted, knowing full well what would happen to me. Bastards. Anyway. Across the street, still standing but no longer operational, it seems, was the Park Place Motel. I lived that summer in one of the bottom-floor rooms, with dad and his wife. It was entirely too cozy, entirely too stifling, entirely too familiar. And yet, I'm thankful for the memories, which quite without my realizing it were becoming fodder and fuel. I've set stories in that park, and in those fields beyond it. With very little disguise (or even much of a name change), I've turned Fairview into a character all its own, the little town of Grandview in This Is What I Want.

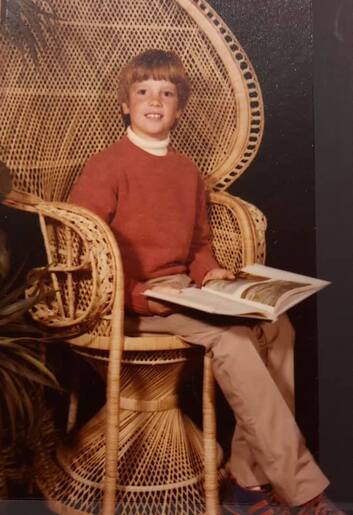

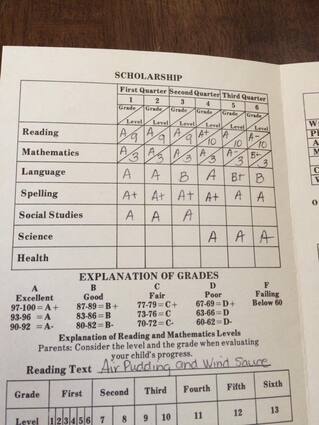

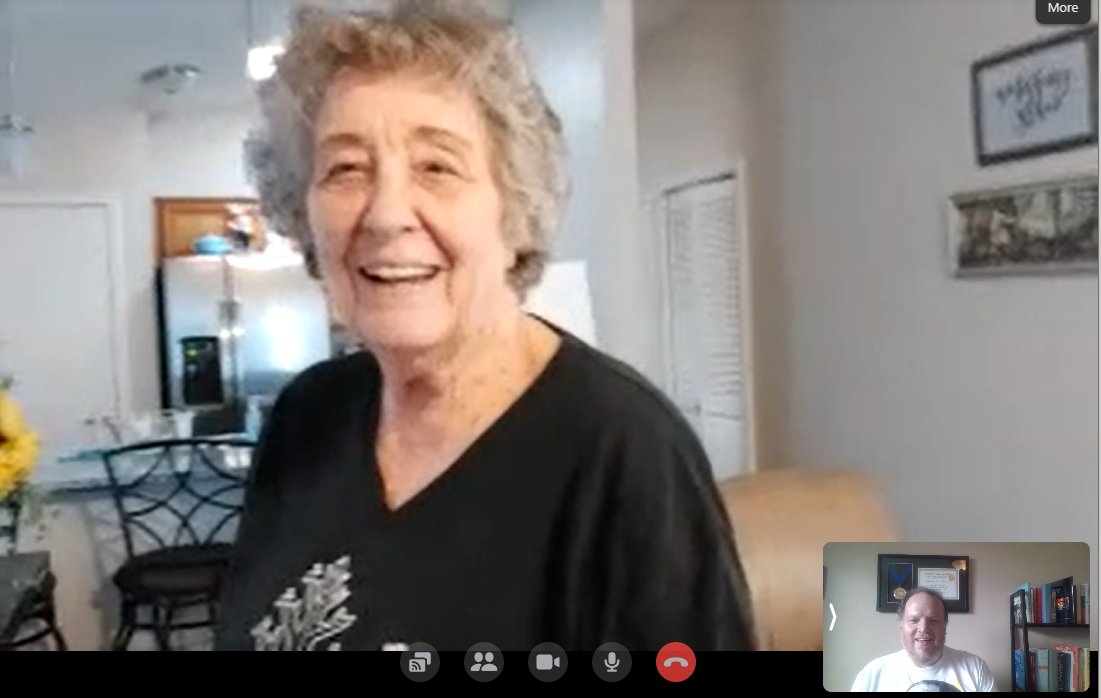

It's all been a gift, every bit of it. I'm grateful, all the time. And I can't wait for the next trip ... 5/25/2022 0 Comments Some Who Shaped Me That's not a chair for reading, son. That's not a chair for reading, son. Today's little trip through the memory banks requires us to visit late summer 1978, a suburb of Fort Worth, Texas, called North Richland Hills, a neighborhood (and its elementary school) called Smithfield. Smithfield, in fact, was what most folks who lived there called the place back then. North Richland Hills, now a sprawling burg of about 70,000 people, was a relatively new concern in those days, having been voted into its own municipality 25 years earlier when Richland Hills, the now much smaller adjacent community, declined to annex the area. By 1960, North Richland Hills had gobbled Smithfield, a freestanding community to its north. The census in 1970 put North Richland Hills' population at just a shade more than 16,000 people. We were 30,000 strong by 1980, so you can sort of suss out the math for '78. We were getting bigger britches, for sure, but we were a cozy group. If you were to cleave off the people who thought of Smithfield as Smithfield, because that's what it had always been to them, you'd be left with an even smaller subset. Anyway, it was a different time and, in its way, a different place from what it is now. I was a different boy. There at the left, that's a pretty good approximation of what I'd have looked like (minus the wicker chair) as I pedaled off on a summer day to our neighborhood school, Smithfield Elementary, to see if the classroom assignments for the coming school year had been posted. When I saw that I had been assigned to Charlotte Cooke's classroom, I know I was overjoyed, for that's the teacher I'd been hoping to get as I moved on from second grade to third. So here's the thing: I didn't spend long in Mrs. Cooke's class. Maybe a week. Maybe less. I don't remember, exactly. What I do remember is that a new third-grade teacher started at Smithfield that year, a newly minted graduate who had been a late hire and was getting her first classroom at our school. As I recall, a class was built for her first by asking for volunteers to shift over from their assigned teacher to this new one. After that, the administration would do it by conscription. Again, here's where the finer details are lost to me in the intervening 44—holy shit, 44!—years, but I do remember that I volunteered. I do remember being concerned that if kids didn't act like they wanted to be part of this new teacher's class, she would get discouraged and think she was unwanted. I am certain—utterly certain—that given my affection for Mrs. Cooke, volunteering wasn't what I wanted. I felt like I needed to do it. Where such a notion came from, I have no idea.  I've made a lot of stupid decisions in my life. Made a lot of fortuitous ones, too, and volunteering for Donna Spurgeon's third-grade class in 1978-79 is a standout in the latter group. I loved her almost from the get-go—I do recall some initial cold feet about leaving Mrs. Cooke's class that my mother told me I'd have to overcome, having made a commitment—and I've loved her straight through. She later had my sister (twice, I think, after she moved up to a fifth-grade classroom), she changed schools and I kept up with her, I visited her classes a few times through the years, I was able to wish her a "well done!" when her retirement came through, and we keep the conversation going on Facebook even today. Back then, in 1978-79, I ended up feeling like I got the best outcome possible. Mrs. Cooke still figured into things, teaching me the perilous math of third grade (fractions!) and breaking me of the annoying habit of making my fours look like nines. But Donna was an all-timer, the kind of teacher I made it a point to keep up with as the seasons changed, for both of us. She started as a teacher (and even raked me pretty hard on my language skills, as evidenced by the report card above), then ended up as a friend. Doesn't get any better than that. So what of Mrs. Cooke. Well ... Sadly, I didn't keep up with her. I liked her, appreciated her, enjoyed her instruction, but time went on and so did I. And so did she. But let's go back to this idea of Smithfield as a place in time and as a heart's memory, just for a second ... There's a dedicated group of people who are from where I'm from, who've stayed, who haven't let the idea of Smithfield get too far away even as its time as a stand-alone town recedes. Every year, first weekend in May, there's a reunion. Living several hundred miles away, as I do and as I have for most of the past 35 years, I've never been to it. That's my failing. This year, I sent a stack of books to be included in a raffle, to hopefully play some small part in keeping these annual get-togethers going. A few days after the event, I got a text message from one of the organizers. She said someone had dropped by, seen the books with my name on them, and remembered me. Charlotte, she wrote. She was Charlotte Cooke, and she's Charlotte Williams now. Well, I'll be damned. A torrent of memory came on. You can see it, in every paragraph above. The organizer, LaDonna Powell, and I launched a conspiracy. We'd send her a book. I'd enclose a card. We'd spring a video chat on her. We'd close this circle that's been hanging open since Jimmy Carter was president. There she is, and there I am, all smiles for our long trip back to each other. I'd like to say I would have known her on sight, on the street, but I probably wouldn't have, and I'm certain she wouldn't have known me. But as we talked—just briefly—I could see the flickers of kindness and care that made her such a wonderful teacher for all those years, one whose classroom I badly wanted to be in when I was 8 years old and rode my bicycle down to the school to see if the luck of the draw had been with me. It had been, and yet I asked to be reassigned, which turned out to be only one of the most consequential decisions of my growing-up years.

Sometimes, it all works out. What I said to Mrs. Williams, in our chat and in the card I included with her book, is between the two of us. In the broad strokes of it, I can say only that I'm grateful. For the kindness of the teachers I've known, whether chosen by me or for me. For the intercession of LaDonna. For the chance to say thank you, and to mean it. Thank you. 1/24/2022 0 Comments My BoyLet me tell you a little something about this boy … As of tomorrow, January 25, he’ll be 3 years old. And because I’m nearly 52 and have learned how fast time seems to go, I have to check myself sometimes against pre-emptively mourning what will happen if the actuarial tables are true for both of us: I’ll have to say goodbye to him and let him go. Most of the time, I can get my head straight, tell myself to enjoy the time I have with him, but sometimes I get fixated not on the past, as is my wont, but on the future. This is one of those times, because he’s hit this milestone. Contrary to the old saying, he's not my best friend. That is and always will be my wife, as she should be. But he’s my best buddy. I’ve lived to an age—and lived through a pandemic, so far—that has calcified my lack of interest in spending great scads of my time with other people. I’d rather stick to my house and my patterns and our tight little circle here, two people and a cat and a dog. I say again: He is my best buddy. He goes where I go. He hears my thoughts. I check in with him, and he checks in with me. We move around each other like an old married couple, which we're not, but it speaks to the familiarity. So, anyway, three years ago … It was Jan. 27, 2019, and Elisa and I were about to step into a movie theater in Brunswick, Maine. Before we did, I checked my email via phone. I had a message from Doxy Den in Mechanic Falls, a breeder (I know, I know—I wanted a dachshund, and this is not a mill; it's a family that loves their dogs): “The puppies arrived on Friday! We had 5 boys! I have 3 black/tan long hair males available! There are pictures up on our Facebook page. Groot, Drax and Rocket are the puppies that are available. Rocket is tiny but strong and doing well. Groot has a little bit of white on his chin and the tips of his toes.” I went to the Doxy Den Facebook page, looked at the pups, and made my choice: I’d take Groot (but not the name). Over the weeks that followed, I watched him grow, from a distance. Because I had a trip back to Montana planned for March, I didn’t pick him up until April 9. He was the last of the five boys to go to his permanent home. The Doxy Den owner’s granddaughter cried because she had to give him up. I cried when I got him to the car on a wintry day, for the long drive home. I'd been waiting on him, and he was finally with me. He spent the better part of an hour and a half trying to crawl from his bed into my lap while I tried to drive. Finally, late in the trip home, he hit the wall (see below). I’ve had many dachshunds, and I’ve loved them all. Just get me going on Sniffer and Mitzi and Zula and Bodie. I loved them equally, but they came to me at different times in my life, and thus their impacts have been different. Fretless’ importance to me has, perhaps, been a little outsized. My world has gotten smaller these past three years. He’s filling more of it than he might have in another time.

Fretless came to me at a time when we lived in a beautiful place that didn’t feel much like home, and we were still struggling with what to do about that. Fretless and I, almost immediately, began taking long walks in the woods, and he helped me make my peace with Maine. In hindsight, I can see how much I needed that. Long may he be with me. We're not near done yet. 11/13/2021 0 Comments Odds and endsDispatches from the staying-in-touch department ...

Will the pig run again? I've written before about my occasional life in pipeline inspection — an association that inspired an entire novel — and had been looking forward to getting out there again in the spring, after the usual wintertime slowdown. Well, maybe, but also looking like probably not. The company for which I did work recently shuttered, and there's an industrywide slowdown, so I may be on the obsolescence end of progress (or regress). I can't say I'm particularly heartbroken. Pipelines are a destructive, invasive way of delivering extractive sources of energy, and for the future of the planet, it's high time we develop alternatives that are well within our grasp but beyond our political will. On the other hand, there's a practical consideration: We already have the damn things, and we're using them. The job I did was essential to the safety end of matters. Let's hope that continues until we can pull those things out of the ground and return the land to those from whom it was stolen. I will miss the travel to exotic (read: remote) locales and the chance to meet people in their natural habitat. But that can be enjoined in other ways, obviously. Union strong I recently did something I should have done a long, long time ago: I joined the Authors Guild. So here's where I cop to self-interest: I began to consider the possibility earlier this year when, quite apart from any involvement from me, my former agency descended into founder-vs.-founder contretemps and my meager royalties from long-ago books started showing up late or not at all. My former agent, also caught in the crossfire as her old shop melted down, was a champion and an ardent defender of my rights, it should be pointed out, and she got my situation squared away, for which I'm eternally grateful. But it occurred to me—again, when my self-interest was compromised, an entirely human condition that I'm trying to rise above—that in this whole solitary business, you have to grab a little solidarity where you can get it and stand strong with those who do what you do. I'm also reminded of something wise I once heard said by A.W. Gray, a well-regarded crime novelist but better known to me as the father of my boyhood best friend: "The people who need unions the most are those who don't have them." 9/24/2021 5 Comments Back to the Fork in the RoadIt's Sunday, September 19, and I'm on Interstate 25 in Casper, the nose of my car pointed north, toward home, a few hours away. I'm tired. My dog, Fretless, lies languidly in the passenger seat. He's had enough after a week away. So have I. Home, my wife, the cat—they all await. We have plenty of gas, had a bite to eat back in Douglas, fifty miles behind us. We have everything we need. The smart play is to get beyond this oil town and open up the cruise control a bit, see what this Toyota can do as we zip back into the emptiness of Wyoming and, eventually, get pulled into the embrace of Montana. So, of course, I exit the interstate, pick my way through downtown Casper, find CY Avenue—I once called it, in a novel, "the spine of the Casper grid system," which may or may not be true—and follow its familiar path to where I turn off for Mills, a little town north of Casper, and as I do, the well-trod memories come at me again. What I've come to see has been seen before, many times, and is likely to be seen many times yet, and if this particular side trip is taken as evidence that my life is in reruns, I will say only this in disputing that notion: Context is important, in all things and especially in this: I find it instructive, or at least perspective-granting, to be reminded of the life I might have had so I can better appreciate the one I'm swimming through. It's Friday, September 24, the day I'm writing this, and I'm reflecting on a spontaneous turn in a phone conversation with my mother this morning as we talked about other things. We talked, quite organically, about a decision she made for both of us in 1973, my third year. I was a capable kid, even at that age, blessed with an ability to carry on conversations with adults, but this matter was beyond my perception. She didn't want to live in Mills, Wyoming, anymore. That was surely half of it. The other half was that she didn't want me to live in Mills, Wyoming, anymore. She looked at the present, our life with my father there and what it seemingly held for us, and she projected out her future and mine and didn't like where those lives seemed likely to end up, and she did something about it. She took us out of there, into life with a man she'd met that year, the brother of her best friend, a man who lived in Euless, Texas. Not that it's anyone's business, but they hadn't had an affair. They'd had a connection, a chance meeting at a party that turned into a deep conversation that blossomed into a friendship and has become a nearly 48-year marriage. We talked about it this morning, Mom and I, this decision that with each passing year strikes me as more and more brave, more and more essential to both of us (and now to so many others—generations of others), more and more the line of demarcation, in strictly selfish terms for me, between where my life was pointed and where it ended up. I can see now, when I'm more than two decades older than she was then, how much gumption it required for her to do what she did. She was alone there, much of the time. She was 28 years old, and while Dad might not have represented maturity or loving or grace (I love the man, but let's be honest about the limitations), our prospects there were much more certain than they were anywhere else. There was a home well on its way to being paid off, an ascendant business, money in the bank. It would have been all too easy to stay. Many people have stayed for less. Mom saw the future and she left. I'll never receive a finer gift. So, you see, Mills, Wyoming, is actually a bit player in this what-might-have-been contemplation. It wasn't Mills we were escaping so much as who was there and what our life was there. It could have happened in Moline or Schenectady or Topeka. Could have, but didn't. This is, at its heart, a human story, a story of a boy with three parents who've imprinted him in wildly varying ways. I love my father, a love that shines through my struggles to understand him and his to understand me. It's a love strong enough to withstand my suspicion that my start in life would have been less than it was had I finished my growing-up years in his house. The math of that situation is inconceivable to me, given the way it all went. It would have been Mom and me in some kind of alignment agaInst the gravity of the way he is, the work that was always taking him away from us, and the instability of the home we were living in. I'm certain Mom's decision all those years ago hurt him. I'm also certain, if Dad can access clarity and honesty, that he'd say it needed to happen. For all of us. And what can a boy like me say about his mother that hasn't been said in better ways by better thinkers? She is pure love when it comes to her children and her children's children, but to leave it at that misses the fullness of who she is. At an age that seems to me, now, to be impossibly young, she was relentlessly wise. She had aspirations for herself (and has them still). To my ongoing gratitude, she could see a time coming when her son would have them, too. In so doing, she brought me into the sphere of the man who became my stepfather. Back then, he was a 31-year-old sportswriter at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, a man who had his own broken first marriage, a son, and regrets. He also had a shared hope with Mom that they could make a go of it together. I can scarcely remember a time before his presence in my life, and he has never, not once, treated me as anything but his own. That has made all the difference. I go back to Mills to remind myself that it could all have gone another way. Could have, but didn't. So what do I make of Mills, all these years later?

I think it would be presumptuous of me to make anything of it beyond my sliver of experience there. It's steeped in nostalgia and memories and wonder. Its presence on the outskirts of my life has been a professional gift, surely (the old memory + imagination thing), as well as fodder for the occasional facile joke. (One could certainly quip about "welcome to Mills, please set your watch back 20 years" or wax irreverent about how hard the wind blows there.) The thing is, I've lived enough places and known enough people to realize something important: Most anyplace can be home, depending on who's doing the inhabiting and what they bring to it. I suspect—but don't know for certain—that my life would have harder and less interesting had I grown up in Mills. It's the not knowing, of course, that makes it such a delicious ponderable. So I go back, and I look around, and I try to imagine who that boy might have been, what kind of man he might have become, where he might have gone and what he might have seen. And because Mom imagined something else entirely, way back in 1973, I can be ever grateful for the real story that lies alongside the conjecture. My friend Caroline Patterson has a new novel coming out Sept. 15. It's titled The Stone Sister, and it promises to be an absorbing, fascinating read. It's getting some fantastic endorsements from the likes of Ann Patchett, Annick Smith, and Kim Zupan. Here's a book trailer: Looks fascinating, doesn't it? Well, go get it.

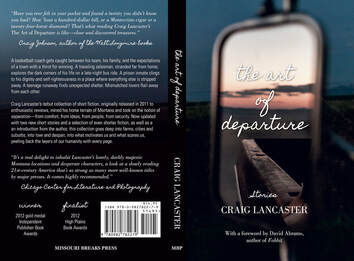

And while you're at it, be sure to check out Caroline's exquisite new website and learn more about her and her work. 8/29/2021 0 Comments A Few Words about 'The Word' Several years ago, I would rope my Facebook friends into this weekly crowdsourced writing project called "The Word." The exercise was not my invention. I lifted it from Janet Fitch after I'd read something from her about it, and it quickly became something I did both on my own time and on those rare occasions when I would lead a writing workshop. It's such a simple concept, full of creative potential: You solicit a single word, then proceed like so: That word inspires a short story that you're to write in a nominal amount of time (say, an hour), and the resulting story must include the word. It's so much fun to give a single word to a large group of writers—say, for example, a group of inmates at the Oregon State Prison, where I led a workshop several years ago—and see the wide diversity of what comes back. So every week for the better part of a year, I'd say something like this on Facebook: "Give me a word. Any word will do. Give it to me." I'd accept suggestions for an hour or so, run a random number generator, choose the corresponding word, then sit down and write. Below is an example of a resulting story, taken from my collection The Art of Departure. If I remember correctly, the word that prompted this one was "squab." It ended up taking quite the backseat in the story it inspired. PonziIn September of that year, our neighbor Wayne had this idea that he could get rich by selling groceries Amway-style, and he booted his twelve-year-old boy out of his own bedroom and put up shelves loaded with packages of spaghetti, cans of roast beef, soda pop by the case and other non-perishable goods. Soon after, Wayne came over to our house and gave my folks the pitch, showed them how, if they just signed up a few friends and those friends signed up a few friends, and so on, they could make as much as $10 million a month, all by making a little bit on every transaction. “Everybody needs groceries,” Wayne said, mopping sweat off the folds of blubber on his neck. “It’s the perfect plan.” My pop liked Wayne, liked going out with him occasionally and tossing back some suds, and he paid the ten-dollar membership fee and accepted the tabbed folder that contained the list of goods and prices, as well as several pages of helpful hints for enrolling friends in the program. “We’ll see what we can do with it, Wayne,” Pop said, showing him to the door. “It’s an interesting idea you have here.” The old man had said something similar a few times before. We still had a shed full of cleaning chemicals that Wayne had foisted on Pop in an earlier scheme. The stuff was supposed to get rid of deep grime on contact, and sure enough, it performed as advertised. It also ate a hole in our carpet. Pop put the stuff in the storage shed because, I think, he didn’t quite know how to dispose of it, and he didn’t want to hurt Wayne’s feelings. A similar sensibility had driven him to sneak out of the house one night and open the door to the pigeon coop Wayne had insisted he build. The next morning, the flock had flown away, and Pop went across the street and told Wayne that they wouldn’t be making that killing on squab. “You’re a soft touch, Leonard,” Mom scolded him, and Pop mumbled something about how it didn’t hurt anything. Mom often said that the old man “enabled” Wayne’s irresponsible behavior; most of Mom’s vocabulary came from the self-help books she consumed with the fervor of the newly touched religious. That idea never seemed to resonate with Pop. Mom thumbed through the folder. “This isn’t going to work.” “Why not?” Pop asked. “Seems like a decent idea. Like Wayne said, everybody needs groceries.” “Yeah, but look at this.” Mom thrust the folder at him. “Now just look at that: Cheer laundry detergent for $2.49. I can get it for a dollar less down at Skaggs. And $1.50 for a two-liter bottle of Coke? I got it for 99 cents yesterday!” It went on like that for another half-hour or so. After the first few broadsides by Mom against Wayne’s plan, Pop looked for an escape. He tuned in to the Texas Rangers game on the radio, while Mom sat at the kitchen table and lingered over the list of products and prices. Their interplay was a series of exclamations in one room and knob adjustments in the other. “Two-ninety-nine for Sanka!” Pop turned up the volume on the radio. “A buck eighty-nine for Doritos!” Pop flipped over to Bill Mack on WBAP. “A dollar-ten for a can of tuna!” The old man turned off the radio and went outside. “Rangers lost,” I said. I held open a lawn bag so Pop could scoop a load of early fallen leaves into it.

“Figures,” he said. I shook the bag to settle the leaves and then tied off the top. Pop fished his smokes from his front pocket and lit up. “I guess Wayne’s idea has a few flaws,” I said. “Guess so.” The old man exhaled a string of smoke from the side of his mouth, upwind of me. “You know, he kicked Ethan out of his own bedroom so he could put food in there.” Pop didn’t say anything, but I could see his jaws clench. He was chewing on something that was giving him trouble. Whatever it was, I knew I’d never hear about it. “Men sometimes lose their way, Jon.” He crushed the cigarette into the brick of the house, behind the hedge where no one would see the mark. “Come on,” he said. “It’s getting late.” 8/23/2021 15 Comments Jon Ehret, My BrotherNot that we’re back in eighth grade or anything, but in the couple of days that this thing has been sitting on my head, wanting to come out through my fingertips even as I had no idea how I would start it or where I would end it or what I would put in the middle of it—and, Jesus, now I’m quoting Seger, what to leave in, what to leave out—I’ve been thinking about a decidedly eighth-grade question: Who’s your best friend? Seriously, who? Is it your spouse, the person you spend the most time with, the person who hears and tolerates and rides out all the stupid shit you say, the person who’s in bed with you, who knows every embarrassing thing, who shares all the same things with you, who knows where the hurts and the hopes and the hesitations are? That would be a good answer, your spouse. In most considerations, yes, that’s absolutely the answer for me. Or is it your work confidant? Your childhood friend who has somehow endured? The high school classmate you didn’t know then but are connected with now and cannot imagine not knowing and loving? Your college roomie? Is it your neighbor, the person in the pew every Sunday at church, the father of your kid’s best friend? Or, maybe, is it someone who has rippled through your life, like a pebble sending slow-moving water rings to the shore? You had something going for a while, then life and distance intervened, then you picked it up and it was just as good as before—no, no, it was better—and then you set it down again, and then it came back one more time and it stuck for good. It has survived decades and losses and different cities and different sensibilities and different marriages and different jobs, and it’s the same thing it always was and it’s also something new, something evolving, something surprising and cherished. Couldn’t the person with whom you share all that be your best friend? Shouldn’t the person with whom you share all that be your best friend? Jon Ehret was my best friend. Jon Ehret is gone. How am I supposed to do this without him? Before I get into the various specific times and qualities and shared experiences that made Jon my friend, I need to answer broadly the question of why it worked for us, why we latched onto this friendship in the last decade of the previous century and saw it through for thirty years. No offense intended, but I don’t need to answer that question for you. The world can go on spinning if you don’t understand it, and while the world certainly will go on spinning if I don’t answer for me, here’s the deal: In hindsight, I can see it, all of it, what we shared and why it mattered and why it stuck. And hindsight is all I have, now. The drive Elisa and I never made to see him and Laura in their new house in Santa Fe, that’s not happening. His invitation for me to head down and meet him in Utah, where he was picking up a rescue bird (there will be more on this), the one I turned aside with “damn, my work schedule” and “invite me on the next one”—there won’t be a next one, and thus there will be no invitation. The last time I was in Buffalo, N.Y., his hometown (there will certainly be more on this), and invited him to fly out and he turned me aside with “damn, I’ll be at a wedding in Texas.” Yeah, that’s not happening, either. It’s all hindsight and memories and smart-ass ripostes on Facebook and a text thread on my phone that I will never erase, in hopes that I can someday bear to look at it again. That’s all there is. So here’s why it happened and why it mattered and why it stuck, and if this is too abstract, you’ll just have to trust me: Jon and I were the same but different, and this is the second time in a week I’ve used those words to describe the way I’m hard-bonded to someone. And because those bonds were so difficult for each of us to find with other people—there’s nothing like the unexpected death of your best friend to serve as a reminder that you make friends broadly but struggle to hold on to them deeply—we held tight to the fact that we found them with each other. I think we always knew what it was, but we took a long time to acknowledge it with a nod and longer still to say it and put wind under the words. We did, though. For that, I’m grateful. I have that, too, and so does he, wherever he’s off to. So, look, I should hope it doesn’t happen to you, but maybe it already has, and the longer you live, the greater the likelihood that it someday will. Your phone rings one bright day, and it’s Laura, and you know it when you hear her voice, because although you’ve known her for as long as you’ve known him, and you love her as much as you love him, he’s still the conduit by which the whole thing goes, and if she’s calling, that must mean Jon cannot, and so here it comes. This all occurs to you in a whisper of a fraction of a second. It’s fucking insane how fast and final it all is. Jon died at work, at the bird rescue center in New Mexico where he had found purpose in semi-retirement. He was in his joy, and then he was gone before his coworkers found him. Fifty-five years old. Heart attack, it would seem. No warning, no chance at intervention and another outcome. Gone. I spent the better part of a decade flat-out ignoring a condition that I knew would kill me if I let it. Jon had a lovely day with his wife, then went off to his birds, and never came home. We’re the same but different. Laura tells you all this, and you remember another phone call, 1993, Owensboro, Kentucky, to Buffalo, New York, and you were the one piercing the bright day and saying our friend, Brian, he’s dead, and Jon says, “Why?” And you realize that’s one hell of a good question, then and now, because it’s the only question you have: Why? Nobody fucking knows why. And you bounce to another memory, Brian and Jon at the center of it, where you’re at work as a sports clerk at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, couldn’t have been later than fall of 1991, and you’re making fun of your boss’ phone manner, because you’re 21 and a smartass, and you pick up a dead phone and say, “Staaaaar-TelegramsportsthisisEd,” because that’s how Ed says it, and all the editors on the desk are laughing, because you’re one funny sumbitch, and you don’t see Ed behind you and he says, “That’s pretty good. Good skill for your next job.” And here’s Brian: “I just got a warm feeling.” And here’s Jon: “That’s not a warm feeling. That’s Lancaster pissing himself.” And here you are, missing them. We met at the Star-Telegram. Jon was 24, and I was 20. He had a master’s degree from the University of Missouri in hand, and I was steadily on my way to bombing out of college for good. The same but different. He liked The Who and King Crimson. I liked Paul McCartney and R.E.M. I was making plans to move to Alaska (for the first time), and he thought that was the coolest thing in the world. I thought he was the smartest guy I knew, a brilliant layout man (we drew them in those days, kids) and someone worthy of emulation. We were big, lumbering guys, often more comfortable in our interior lives than we were on the outside. I covered up with a sort of zany bearing and kept a lot of my deeper thoughts to myself. Jon balanced anger and the most generous heart I've ever known. The same but different. Later, the connections went deeper. A weekend with the Ehrets after he and Laura moved to Buffalo, a day trip to Niagara Falls, an introduction to Newcastle Brown Ale, before it went all corporate. A snowy night, the last of the trip, when we ordered in and he urged me to get a cheeseburger sub and when I hesitated, he was all, “Man, it’s a cheeseburger on better bread. What’s the problem?” No problem at all. Delicious. And while we had surely eaten meals together before then, in my memories that’s the line of demarcation where shared food experiences became part of the deal: Jak’s in West Seattle, barbecue in Texas, seafood in Damariscotta, a legendary birthday meal at Walkers here in Billings on a minus-12-degree day, his urging me toward Ted’s Hot Dogs and Duff's in Buffalo, and my going to both, every time I'm there, even though we were never again there together, now much to my eternal regret. “Buffalo is a great fatboy town.” I say it. I live it. Jon said it first. In 1996, I decided, after some consideration, to seek out my birthmother. I told Jon what I was doing, because I knew Jon would have both an appreciation and a point of view, as an adoptee himself. He didn’t tell me not to, but he presented every you-oughtta-be-careful-here he could think of. He said he couldn’t imagine doing it. I did it anyway. Many years later, when he could imagine such a thing, I could give him some on-the-ground intel. I could validate the things he got right, contradict the ones he got wrong, and throw up flags around the ones neither of us thought of. He did it anyway. And, our being the same but different, we had more to talk about, in conversations that had the width and breadth and depth of galaxies. The kind we had so much difficulty having with other people and yet never had trouble getting into together. Another night of spotty sleep draws near, so let me just wrap it up this way:

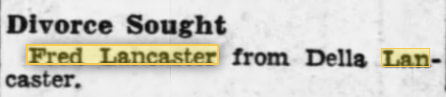

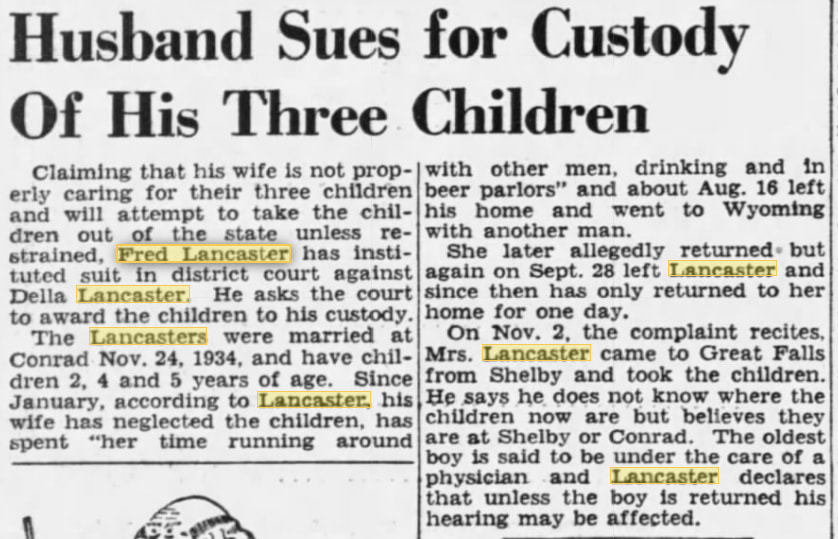

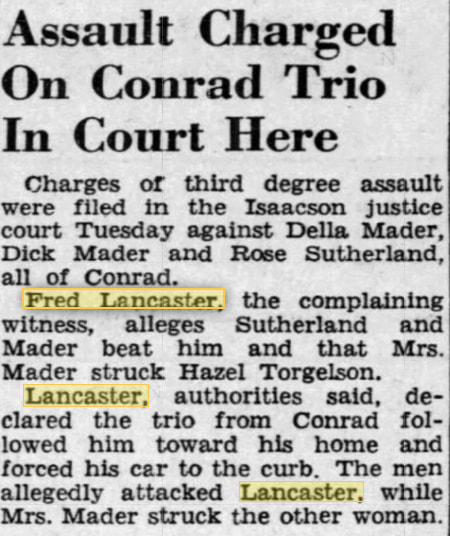

I have four brothers in a family line that looks like a tangle of kudzu more than it does a tree. There’s the brother I inherited when my mother and my stepfather got together. We lost him four years ago. There’s another who was born to that union. And there are two half-brothers who came with the search for my birthmother, the one I pressed forward with despite Jon’s admonitions, just as he pressed forward later with his own quest and his own questions. Neither of us, I think, would turn aside the decision we made after it was done. The same but different. Then there’s the fifth brother, the one I chose, and the one who chose me. I know he’s my brother because he told me so, and because I told him so, and because he was the kind of guy who didn’t use words he didn’t intend, and he told me these a long time ago: If you ever need anything at all, you tell me, OK? I took him up on it, too, in ways that seemed picayune at the time and register even more inconsequentially now. I was lucky, I guess. I never needed anything substantial and life-changing. A kidney. A roof over my head. A slayer of the wolves at the door. You know, the biggies. A heart. He filled mine. He broke it, too, just the other day. I’ll patch it up. He lives there now. 7/13/2021 0 Comments Down the Rabbit Hole …... and into the rest of the story, or at least more of it. I've been on the masthead of Montana Quarterly for the better part of a decade now. But back in 2010, when I had one novel to my name and not much else in the way of published literary work, I was just a guy pitching an essay to Megan Regnerus, then the magazine's editor and now our beloved editor emeritus. I called it The Small Things, and it was written after my father, Ron, and my Uncle Bob Witte (RIP) ventured out to the Fairfield Bench, near Great Falls, and found the dairy farm that shaped Dad's young life in some pretty horrible ways. I won't say much else here; you can read the piece for yourself, and I hope you will, because it provides a good anchoring for some discoveries I recently made while digging through archives. Long story short: I've always wondered about some of the details my father told me that day on the bench, not because I thought him dishonest about the general gist of things, but because he was 71 years old (he's 82 now), and that's a lot of time for the finer points to get lost. But he hadn't lost them. Not really. Let's dig in ... From the piece: "I’d heard, or maybe I’d assumed, that my paternal grandfather, Fred, had walked out on the family when Dad was two or three years old. But here was Bob, telling me that it had been a proper divorce and that Dad’s mother had rejected the children." The archives say ... Pretty much dead-on, if Fred's account of it is to be believed. He sought the divorce. He also tried to get the children (Dad, his older brother Duaine, his older sister Dolores). From the piece: "When Fred showed up to get Dad a week later, Dick locked the little boy in the basement and met Fred at the road. He carried a shotgun, all the better to send Fred on his way. Three children could accomplish a hell of a lot more work than two, and Dick aimed to keep Dad close, be it with a gun or a fist or a horse whip." The archives say ... Nothing I found speaks directly to this episode. Still, I'm not about to contradict Dad; he remembers it, he's shaken by it all these years later, and trauma has a way of imprinting itself immutably. What I know for sure is that Fred and Della and the man who became her new husband, Richard Mader, had confrontations. Here's the evidence: I've saved the best one for last. The remembrance of my father that was shrouded in the most mystery was where he went and what he did when he finally ran away from Richard Mader's dairy farm for good. Dad's memory is that he went to work for a farming family near Three Forks. I had no reason to disbelieve him, of course, but Three Forks is a fair distance from Fairfield. I wondered how he got there and whether he might have actually ended up somewhere else, somewhere closer, and just lost the place to the intervening years. Nope. From the piece: "After a few weeks, he ended up on a farm in Three Forks, doing odd jobs and being attended to by a kind family that kept him shielded from Dick, who was still looking for him. After a year or two, Dad told the farmer that he would like to see his father again, and the man agreed to find Fred and take Dad to him. A few weeks later, word came: Fred was in Butte. "More than fifty years later, Dad’s voice broke and his eyes floated in tears as he revealed what happened next. They were the only emotions he betrayed in telling the story. “'The farmer told me, "I’ll drive you to Butte and once you’re there, I’ll put you in a cab and follow you to your father’s house. Once I see that he’s come out to get you, I’m gone." ' "In a singular act, that Three Forks farmer, whose name has been lost to the intervening years, did for Dad what no one else could be troubled to do: He acted in the best interest of the child." The archives say ... Well, just have a look from a newspaper's "persons sought" column:  Dad, early 1960s. Dad, early 1960s. Getting at the details of my father's life has been a driving pursuit for many of my own days. Part of it is that I'm his only child, and if there's a story to be salvaged, it's up to me to mine it and tell it. And part of it is that I'm so heartbroken for the boy he once was, a clearly smart youngster who was denied so many of the blessings of his age, who was brutalized and stunted and who has persevered despite it all. I know how violence cycles from generation to generation, and I also know that the man I call Dad has refused to spin it on into me. It's the great achievement of his life, and he probably doesn't even know it. I want to drag the shit that happened to him into the light, the best disinfectant for what was visited upon him. He's not a hero. He is, in fact, a deeply flawed man (as is his son, as was his own father—there's more to that story, for another time). But he's my dad, and I love him. Addendum: There's an earlier piece, originally published by the San Jose Mercury News in 2004, that focuses more on finding out what became of Fred after Dad reunited with him in the mid-1950s. That was the last time father and son saw each other. Dad went into the Navy, and Fred went ... well, that's the interesting thing. You can read about that here. |

About CraigCraig Lancaster is an author, an editor, a publication designer, a layabout, a largely frustrated Dallas Mavericks fan, an eater of breakfast, a dreamer of dreams, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle. And most of all, a man who values a T-shirt. Archives

July 2024

By categoryAll 600 Hours Of Edward And It Will Be A Beautiful Life Awards Books Bookstores Community Connection Craft Craig Reads The Classics Dreaming Northward Education Edward Adrift Family Geography History Libraries Memory Montana NaNoWriMo Northward Dreams People Plays Poetry Public Policy Q&A Social Media Sports Stage Texas The Fallow Season Of Hugo Hunter The Summer Son This Is What I Want Time Travel Work Writers Writing Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed